CHAPTER 32 Inferior-central Flap Mastopexy with Pectoralis Strip

Key Points

Introduction

Breast hypertrophy and ptosis can cause considerable physical and emotional suffering including low self-esteem, fears of sexual embarrassment, difficulty with sports and exercise, and limited clothing or brassiere options.1 Physical discomfort can include back and neck pain, as well as shoulder grooving and intertrigo. Many of these symptoms can be alleviated by different techniques of mammaplasty.2

Breast reduction and mastopexy techniques have changed dramatically during the last century. New knowledge of vascular anatomy led to the evolution of pedicle techniques, which provided reliable blood supply to the nipple–areola complex. Parenchyma and skin resection patterns have also changed over time. The great advances by Wise,3 Pitanguy,4 Lassus,5–7 Lejour,8–10 Hall-Findlay,11,12 Benelli,13 Sampaio Góes14 and others have brought us significant advances to reach a better shape of the breast. These techniques have not only simplified the operative plan, but have contributed to a shorter scar and a more aesthetic breast. This chapter describes some maneuvers designed to give a better shape with the maintenance of upper pole fullness. The main technical detail involves the use of a chest wall based flap of breast tissue, which is transposed into the upper pole of the breast and held in place by a strip of pectoral muscle under which it is passed and supported further by sutures from dermis to the pectoralis fascia. The technique can be used with standard inverted-T incisions, vertical incisions with short transverse components, L-shaped, or pure vertical incisions.

Vertical Mammaplasty: Advantages and Disadvantages

Although the history of vertical mastopexy dates back to Lotsch15 and Dartigues,16 and later extended to breast reduction by Arié,17 it was otherwise lost to surgical history until Lassus5–7 resumed interest in the 1960s. Using adjustable markings, an upper pedicle for the areola, and central breast reduction, Lassus has employed vertical reduction mammaplasty in a wide range of breast hypertrophies. It was then modified and popularized by Lejour8–10 and other authors.18,19

Lejour modified Lassus’s technique by including wider inferior skin undermining to promote skin retraction and to reduce scarring, sutures to the lower gland to remove tension and to create a stable shape that eliminated reliance on the skin envelope, and liposuction to mold the breast and remove tissue prone to absorption with weight loss.8–10 Lejour’s technique was recognized widely to reduce scarring, improve breast contour, and produce more stable aesthetic results. Beside the excellent long-term outcomes, the long learning curve and the unattractive appearance during the immediate postoperative period caused most plastic surgeons, especially in the United States, to abandon the vertical reduction mammaplasty for procedures with which they were trained and comfortable, usually some variation of the inferior pedicle inverted T shaped techniques.18

More recently, based on some principles developed by Lassus and Lejour, Hall-Findlay described an original technique of vertical reduction mammaplasty. Innovations included a medial pedicle, no skin undermining, no pectoralis fascia sutures, and limited liposuction only to refine the operated breast.11,12 The technique was a notable advance in shortening the learning curve, reducing total operating time, and simplifying the vertical reduction mammaplasty. After Hall-Findlay’s technique description, acceptance of vertical mammaplasty in United States increased. A 2001 survey among American surgeons showed that vertical scar breast reduction was performed in 53% of US patients and has surpassed the rate for inverted T-scar breast reductions.20

Although the classic inverted T incision mammaplasties are easy learning techniques for young plastic surgeons and give more reproducible results on the operating table, they have several drawbacks that should be reassessed.21,22 The short vertical limb dogma (near 5 cm), associated with the inferior horizontal pattern resection of the skin and parenchyma leads the breast to a broad and flat cone shape, with poor projection, and which tends to worsen with time.19,21,23

Although most patients find the standard inverted T mammaplasties satisfying, have their general expectations fulfilled, exhibit physiologic improvements, and experience relief of psychological distress, one-third still find the resulting scars unacceptable.24 These undesirable scars can be quite long, extending medially and laterally beyond the boundaries of the brassiere, becoming visible and unsightly.5,18,21,23 Even more, they are susceptible to hypertrophy, particularly in younger women who tend to scar more easily, or dark-pigmented women who may be prone to hypertrophic scar formation.25 An additional problem with these techniques, especially if they utilize an inferior pedicle for nipple–areolar blood supply is the persistence of ptosis of the central third of the gland (the bulk of the pedicle) creating the ‘bottoming out’ look.

The psychological impact of these scars should not be underestimated. In 1987, a survey involving all members of the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons found that 11% of respondents had been sued by patients dissatisfied with the outcome of their breast reduction. The appearance of scars was the most commonly cited reason for litigation.26 Therefore, if absence of scars in the visible part of the cleavage is the desire of the patient, the plastic surgeons must take this wish into account when deciding which of the currently available reduction mammaplasty techniques is more appropriate.

Since the inverted T approach relies primarily on skin tension to shape the breast, and because skin under tension stretches with time, the long-term result is often a widened, flattened and unattractive breast mound. An additional drawback is the frequency of delayed healing or dehiscence at the confluence of the vertical and transverse limbs of the closure.18,22

Vertical mammaplasty, however, also has its own drawbacks. Current criticisms of vertical techniques include immediate postoperative results that are often not pleasant, problems with nipple–areola complex malposition and irregularities, excessive lower pole and vertical scar length, wound healing problems due to vertical skin-gathering suture technique to reduce the scar length, and lower pole deformities including skin excess (’dog-ears’) in the distal part of the vertical incision. Revision of the vertical scar or a secondary, horizontally oriented excision of the excessive dog-ear tissue have been reported to be necessary in 16–28% of vertical scar breast reductions.18,19,22,27,28

Technical Modifications

In an effort to reduce the disadvantages inherent with vertical mammaplasty, we have proposed some technical changes.29–31 In order to avoid a long vertical component of the scar, a fixed vertical length of 5–7 cm is marked. Once the vertical limbs are established, a curved line is drawn from the proposed superior edge of the areola to the upper point of the vertical limbs, which incorporates the remaining skin redundancy which will be closed around the areola with a purse string suture. The upper pole fullness is improved using a non-areolar dermolipoglandular flap. This flap is based centrally over the pectoralis major muscle, receiving its blood supply through perforator vessels at the level of the fourth and fifth intercostal spaces. This flap is held in place by passing it under a loop of pectoralis muscle and by sutures from the dermis of the flap to the pectoralis fascia. Finally, to reduce the incidence of dog-ears in the distal part of vertical incision, and in attempt to avoid secondary scar revisions, two technical details have been routinely performed. First, the triangular area located from the distal third of vertical incision down to the original inframammary fold is undermined and excessive subcutaneous tissue is resected. Second, when closing the vertical incision, interrupted dermal sutures are used to anchor the skin edges superiorly, over the plicated pillars.

Non-areolar Central Pedicle Flap and Pectoralis Strip

The goal of a vertical mammaplasty should be minimal scar and preservation of an ideal breast shape. In order to obtain a better long-term outcome, it is mandatory to redefine breast shape with internal tissue, not only with skin sutures, avoiding exaggerated scar tension. A strategy created to achieve better upper pole fullness was the incorporation of the chest wall based flap first described by Ribeiro.32

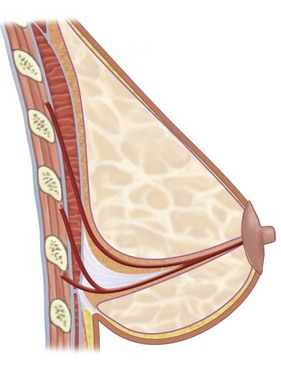

At the time the inferior pedicle flap was first created, it was thought to have the vascular supply related to the inferior dermal plexus. In 1976 Robbins advocated the preservation of all the vessels entering the base of the flap from the chest wall.33 It was only with cadaver dissections that the main sources of blood flow to the inferior pedicle flap were established: the perforating and intercostal branches of the internal mammary artery and the external branches of the lateral thoracic artery.34,35 Based on this, care must be taken during the flap dissection to preserve these vessels which emerge from the pectoralis major muscle at the level of fourth and fifth intercostal spaces, together with a septum of dense connective tissue that divides the breast into a cranial and a caudal part36 (Fig. 32.1). The chest wall based flap consists of the breast tissue located inferiorly to this septum, so it is important to maintain the vessels from the fifth intercostal space inside the flap.

Fig. 32.1 Illustration of blood supply source to the non-areolar central pedicle flap (after Würinger36).

Beside the utilization of the chest wall based flap to fill the upper pole, it was demonstrated that passing the flap under a sling of pectoralis major muscle37 promotes longer maintenance of breast shape, with the vertical scar placed above or at the level of the new inframammary crease.29–31

Operative Technique

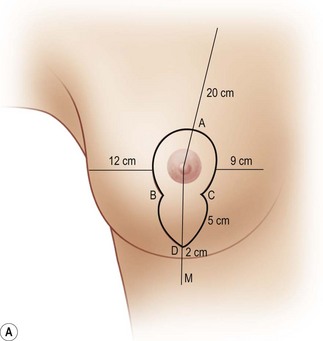

The same skin markings can be used to perform either breast reduction or mastopexy, the only difference being during surgery when tissue resection is carried out as indicated. With the patient in an upright position, a line from the sternal notch to the xiphoid process is drawn (midline). The meridian line is drawn from the mid-clavicle to the nipple–areola complex, and continues vertically crossing the inframammary crease (‘M’ point) at about 12 cm from the midline. Point ‘A’ is marked at 16–20 cm from the clavicle or 18–22 cm from the sternal notch depending upon the projected size of the breast and the length of the chest. Moving the breast laterally, a medial vertical line is drawn in the projection of the meridian line. Similarly, pulling the breast medially, a lateral line is drawn through breast meridian projection. Both vertical lines start at point A and join ending 2–4 cm above the point M, characterizing the point ‘D.’ Points ‘B’ (lateral subareolar point) and ‘C’ (medial subareolar point) are marked over the vertical lines, 5–7 cm above the point D. Point C is located about 9 cm from midline, and point B about 12 cm from anterior axillary line. A periareolar curved line is marked in an oval shape, passing through points B-A-C (Fig. 32.2A, B).

Surgery begins with superwet liposuction in the lateral part of the breast and trunk to improve the body contour (Fig. 32.3). The marked area between points A, B, C, and D is de-epithelialized. The dermis is incised along the marked lines, up to 1.5–2 cm superior to points ‘B’ and ‘C,’ sparing the upper portion of the areola, which is the pedicle for the nipple–areola complex (Fig. 32.4). The dermis is also incised horizontally 1 cm inferior to the areola and subcutaneous tissue is incised perpendicular to the plane of the thoracic wall, reaching the pectoral fascia at the level of the fourth intercostal space. Great care must be taken not to incise in a caudal direction so as to protect the vascular supply.

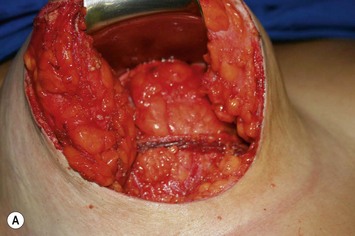

To create the chest wall based flap, medial and lateral vertical incisions are made obliquely through the breast parenchyma down to the pectoralis fascia, leaving enough breast tissue on either side to preserve breast pillars (Fig. 32.5A). Above this flap, breast tissue is undermined from pectoral fascia up to the level of the second intercostal space. The lower portion of the parenchyma flap is dissected carefully down to the original inframammary crease, leaving breast skin flaps 0.5–1 cm thick. This maneuver widens the inferior portion of the breast flap. Superiorly, the flap usually is 6–8 cm wide and 4 cm thick (Fig. 32.5B).

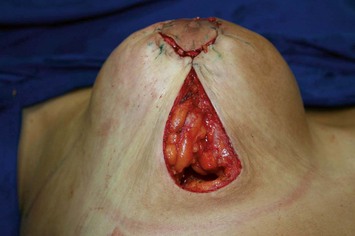

The pectoralis strip consists of a 2 cm wide bipedicled flap, which includes the fascia and partial thickness of the pectoralis major muscle. It is dissected just superiorly to the base of the dermolipoglandular flap, long enough to accommodate the breast flap under it without causing any compression (Figs 32.6–32.8). The usual length of the muscle sling is 8–10 cm. The donor area of the muscle is closed by two interrupted sutures of 2-0 nylon. Then the flap is passed under the muscle sling (Fig. 32.9) and fixed to the pectoralis fascia by a running suture of 2-0 nylon, reaching the second intercostal space. The size of this flap is similar to a 100–200 cc implant, and adds volume to the upper pole of the breast. Because tension on the pedicle is modest, strangulation of the flap has never been encountered.

At this stage, breast tissue excess is excised as a wedge mainly from the lateral and central part of the breast (Fig. 32.9). Sometimes resection of the entire base of the breast is necessary for greater reductions of the breast size. It is important not to resect tissue from the medial pillar to avoid flattening the medial part of the breast. The upper part of the breast is then suspended and sutured to the pectoralis muscle at the level of the second intercostal space, just above the most superior part of the chest wall based flap. This maneuver also helps to correct breast tissue ptosis, restoring the upper pole fullness, bringing together the medial and lateral pillars, and improving the breast shape (Fig. 32.10A, B). The medial and lateral pillars are sutured together in an inferior to superior fashion using 2-0 nylon sutures (Fig. 32.11). To close the skin and reduce wound tension around the areola, a round block suture is made all the way around the periareolar skin. This is a running suture passing through the deep dermis of the outer skin and the areolar deep tissue (Fig. 32.12). The deep dermis of the vertical wound is sutured placing together the subareolar points ‘B’ and ‘C.’ Starting from point ‘D,’ interrupted dermal sutures anchor the vertical wound to the deep pillar tissue, so the vertical scar is kept at the same level as the new inframammary crease (Fig. 32.13). A running intradermal suture with 4-0 Monocryl closes the skin and also helps to shorten the vertical scar (Figs 32.14–32.18). No suction drainage is used.

Fig. 32.13 Deep dermis of the vertical wound is sutured placing together the subareolar points B and C.

1 Kerrigan CL, Collins ED, Striplin D, et al. The health burden of breast hypertrophy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1591-1599.

2 Blomqvist L, Eriksson A, Brandberg Y. Reduction mammaplasty provides long-term improvement in health status and quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106:991-997.

3 Wise RJ. A preliminary report on a method of planning the mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1956;17:367.

4 Pitanguy I. Mammaplasty. Study of 245 consecutive cases and presentation of a personal technic. Rev Bras Cir. 1961;42:201-220.

5 Lassus C. A technique for breast reduction. Int Surg. 1970;53:69.

6 Lassus C. Breast reduction: evolution of a technique – a single vertical scar. Aesth Plast Surg. 1987;11:107-112.

7 Lassus C. A 30-year experience with vertical mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:373.

8 Lejour M, Abboud M. Vertical mammaplasty without inframammary scar and with breast liposuction. Perspect Plast Surg. 1990;4:67-90.

9 Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty and liposuction of the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:100.

10 Lejour M. Vertical mammaplasty: update and appraisal of late results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:771-781.

11 Hall-Findlay EJ. A simplified vertical reduction mammaplasty: shortening the learning curve. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:748-759.

12 Hall-Findlay EJ. Pedicles in vertical breast reduction and mastopexy. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29:379-391.

13 Benelli L. A new periareolar mammaplasty: the ‘round block’ technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 1990;14:93-100.

14 Sampaio Góes JC. Periareolar mammaplasty: double-skin technique with application of mesh support. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29:349-364.

15 Lotsch F. Uber Hangebrustplastik. Zentralbl Chir. 1923;50:1241.

16 Dartigues L. Traitement chirurgical du prolapsus mammaire. Arch Franco Bel Chir. 1925;28:313.

17 Arié G. Una nueva téchnica de mastoplastia. Rev Lat Am Cir Plast. 1957;3:22.

18 Chen CM, Warren SM, Isik FF. Innovations to the vertical reduction mammaplasty: making the transition. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;50:579.

19 Pallua N, Ermisch C. ‘I’ Becomes ‘L’: modification of vertical mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:1860.

20 Menke H, Eisenmann-Klein M, Olbrisch RR, Exner K. Continuous quality management of breast hypertrophy by the German Association of Plastic Surgeons: a preliminary report. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;46:594.

21 Ramirez OM. Reduction mammaplasty with the ‘owl’ incision and no undermining. Plast Reconst Surg. 2002;109:512.

22 Atiyeh BS, Rubeiz MT, Hayek SN. Refinements of vertical scar mammaplasty: circumvertical skin excision design with limited inferior pole subdermal undermining and liposculpture of the inframammary crease. Aesth Plast Surg. 2005;29:519-531.

23 Daane SP, Rockwell WB. Breast reduction techniques and outcomes: a meta-analysis. Aesth Surg J. 1999;19:293.

24 Hughes LA, Mahoney JL. Patient satisfaction with reduction mammaplasty: An early survey. Aesth Plast Surg. 1993;17:345.

25 Ofodile FA, Bendre D, Norris JE. Cosmetic and reconstructive breast surgery in blacks. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;76:708.

26 Hoffman S. Reduction mammaplasty: a medicolegal hazard? Aesth Plast Surg. 1987;11:113.

27 Chen CM, White C, Warren SM, Cole J, Isik FF. Simplifying the vertical reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:162.

28 Spear SL, Howard MA. Evolution of the vertical reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:855.

29 Graf R, Biggs TM, Steely RL. Breast shape: a technique for better upper pole fullness. Aesth Plast Surg. 2000;24:348-352.

30 Graf R, Biggs TM. In search of better shape in mastopexy and reduction mammoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:309-317.

31 Graf R, de Araujo LRR, Rippel R, et al. Reduction mammaplasty and mastopexy using the vertical scar and thoracic wall flap technique. Aesth Plast Surg. 2003;27:6.

32 Ribeiro L. A new technique for reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;55:330-334.

33 Robbins TH. A reduction mammaplasty with the areola-nipple based on an inferior dermal pedicle. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:64-67.

34 Courtiss EH, Goldwyn RM. Reduction mammaplasty by the inferior pedicle technique. An alternative to free nipple and areola grafting for severe macromastia or extreme ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:500-507.

35 Levet Y. Posterior pedicle: anatomoclinical concept of mammaplasty. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 1993;38:463-468.

36 Würinger E, Mader N, Posch E, Holle J. Nerve and vessel supplying ligamentous suspension of the mammary gland. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:1486-1493.

37 Daniel MJB. Mammaplasty with pectoral muscle flap. Presented at 64th American Annual Scientific Meeting, Montreal, 1995.