Infectious Mononucleosis

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Describe the etiology, epidemiology, and signs and symptoms of infectious mononucleosis.

• Explain the immunologic manifestations of infectious mononucleosis, including heterophile antibodies.

• Discuss the elements of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) serology and the diagnostic clinical applications of the presence of each component.

• Analyze and apply laboratory data to a case study.

• Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions.

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Compare the serologic procedures and clinical applications of the Paul-Bunnell, Davidsohn differential, and rapid agglutination techniques.

Laboratory Diagnostic Evaluation

In addition to clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory testing is necessary to establish or confirm the diagnosis of infectious mononucleosis (Table 22-1).

Table 22-1

Classic Laboratory Findings in Acute Infectious Mononucleosis

| Assay | Result |

| Heterophile antibody test | Positive |

| Anti-VCA IgM | Elevated titer |

| Liver enzymes | Elevated |

| Leukocyte differential | Increased number of variant (atypical) lymphocytes |

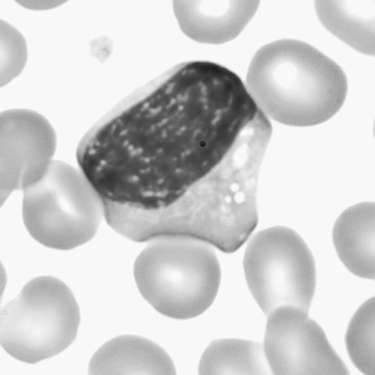

Hematologic studies reveal a leukocyte count ranging from 10 to 20 × 109/L in about two thirds of patients; about 10% of the patients demonstrate leukopenia. A differential leukocyte count may initially disclose a neutrophilia, although mononuclear cells usually predominate as the disorder develops. Typical relative lymphocyte counts range from 60% to 90%, with 5% to 30% variant lymphocytes. These variant lymphocytes exhibit diverse morphologic features and persist for 1 to 2 months and as long as 4 to 6 months (Fig. 22-1).

Immunologic Manifestations

Heterophile Antibodies

• Reacts with horse, ox, and sheep erythrocytes

• Absorbed by beef erythrocytes

Epstein-Barr Virus Serology

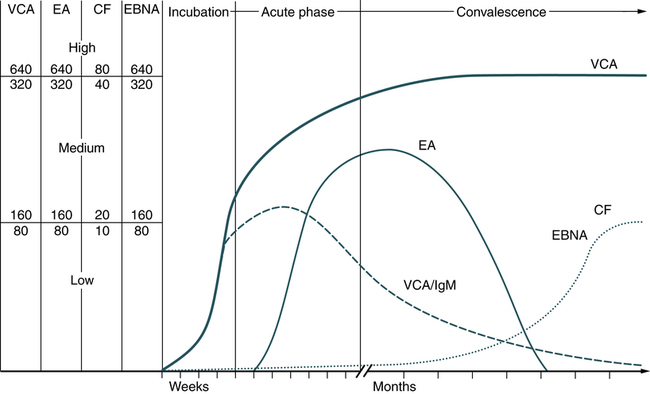

Epstein-Barr–infected B lymphocytes express a variety of new antigens encoded by the virus. Infection with EBV results in the expression of viral capsid antigen (VCA), early antigen (EA), and nuclear antigen (NA), with corresponding antibody responses. Assays for IgM and IgG antibodies to these EBV antigens are available. EBV-specific serologic studies are beneficial in defining immune status, and their time of appearance may indicate the stage of disease (Fig. 22-2; Table 22-2). This can provide important information for the diagnosis and management of EBV-associated disease. Patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma have elevated titers of IgA antibodies to EBV replicative antigens, including VCA. These antibodies, which frequently precede the appearance of the tumor, serve as a prognostic indicator of remission and relapse.

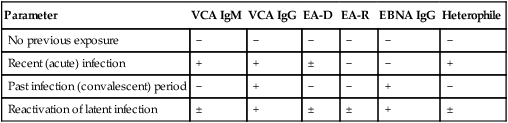

Table 22-2

Characteristic Antibody Formation in Infectious Mononucleosis

| Parameter | VCA IgM | VCA IgG | EA-D | EA-R | EBNA IgG | Heterophile |

| No previous exposure | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Recent (acute) infection | + | + | ± | − | − | + |

| Past infection (convalescent) period | − | + | − | − | + | − |

| Reactivation of latent infection | ± | + | ± | ± | + | ± |

Epstein-Barr Nuclear Antigen (EBNA)

Test results of antibodies to EBNA should be evaluated in relation to patient symptoms, clinical history, and antibody response patterns to VCA and EA to establish a diagnosis (Table 22-3). The antibody profile can be especially useful. For example, a patient with an infectious mononucleosis–like illness caused by reactivation of a persistent EBV infection resulting from an immunosuppressive malignancy or nonmalignant disease can demonstrate high titers of IgM and IgG VCA antibodies. If the antibody to EBNA is also elevated, however, a diagnosis of primary EBV infection can be excluded.

Table 22-3

Characteristic Diagnostic Profile of Epstein-Barr Virus

| Stage | Description |

| Susceptibility | If the patient is seronegative (lacks antibody to VCA) |

| Primary infection | Antibody (IgM) to VCA is present; EBNA is absent. High or rising titer of antibody (IgG) to VCA and no evidence of antibody to EBNA after at least 4 wk of symptoms |

| Reactivation | If antibody to EBNA and increased antibodies to EA are present, patient may be experiencing reactivation. |

| Past infection | Antibodies to VCA and EBNA are present. |

VCA, Viral capsid antigen; EBNA, Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen; EA, early antigen.

Davidsohn Differential Test

Davidsohn Differential Test

Principle

This classic procedure distinguishes between the heterophile antibodies that agglutinate the antigen-bearing erythrocytes of sheep. The differential nature of the test is predicated on the fact that sheep and beef (ox) erythrocytes bear some common antigens not present on the kidney cells of the guinea pig. Exposure of patient serum to guinea pig cells, which are rich in Forssman antigen, and to beef erythrocytes, which are poor in Forssman antigen, produces differential absorption. Any absorbed antibodies are removed by centrifugation and the supernatant fluid is tested with sheep erythrocytes. This classical test differentiates the heterophile types of antibody associated with infectious mononucleosis or serum sickness (Table 22-4).

Table 22-4

Agglutinins for Sheep Erythrocytes in Human Serum

| Type of Serum | Absorbed by Guinea Pig Kidney | Absorbed by Beef Erythrocytes |

| Normal | Positive (+) | Negative (−) |

| Infectious mononucleosis | Negative (−) | Positive (+) |

| Serum sickness | Positive (+) | Positive (+) |

See ![]() for the procedural protocol on the Evolve website.

for the procedural protocol on the Evolve website.

MonoSlide Test

MonoSlide Test

Principle

Sources of Error

For accurate results, only clear, particle-free serum or plasma specimens should be used.

Chapter Highlights

• Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a DNA virus, is the cause of infectious mononucleosis.

• An estimated 95% of the world’s population is exposed to EBV, making it the most ubiquitous virus known. The virus infects B lymphocytes. Although transmitted primarily by infectious oral-pharyngeal secretions, EBV may also be transmitted by blood transfusion and transplacentally.

• The frequency of seronegative patients is almost 100% in early infancy but declines with increasing age to less than 10% in young adults. After primary exposure, a person is considered immune and generally no longer susceptible to overt reinfection.

• In Western societies, primary exposure to EBV occurs in two waves among children and adolescents. EBV is only a minor problem for immunocompetent persons but can become a major concern for immunocompromised individuals.

• The antibodies present in infectious mononucleosis are heterophile and EBV antibodies.

• EBV-infected B lymphocytes express a variety of new antigens encoded by the virus. Infection with EBV results in the expression of viral capsid antigen VCA, early antigen EA, and nuclear antigen NA, with corresponding antibody responses. Assays for IgM and IgG antibodies to these EBV antigens are available.

• EBV-specific serologic studies are beneficial for defining immune status. The time of antibody appearance may indicate the stage of the disease.