Chapter 41 Infectious diseases

EDITOR’S COMMENT

Remember: There is mandatory reporting to your local public health unit of some infectious diseases (see Table 47.2).

ANTIBIOTIC PRESCRIBING

Antibiotic recommendations in this book are largely based on Therapeutic guidelines.1

| M | Microbiology guides therapy wherever possible. |

| I | Indications should be evidence-based. |

| N | Narrowest spectrum required. |

| D | Dosage appropriate to the site and type of infection. |

| M | Minimise duration of therapy. |

| E | Ensure monotherapy in most situations. |

MULTI-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS (MRSA)

MRSA is resistant to beta-lactam and one or more other antibiotics. Initially it was only present in the healthcare setting, but now it has independently evolved in the community, hence the use of the term community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) versus hospital-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA).2 It is all MRSA.

Some MRSA strains are sensitive to antibiotics such as clindamycin, doxycycline or trimethoprim + sulfamethoxazole and are therefore sometimes referred to as non-multi-resistant oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (NORSA).2 These strains manifest clinically as subcutaneous abscesses and necrotising pneumonia.

SEPSIS

(See also ‘Septic shock’ in Chapter 11, ‘Shock’.)

Early aggressive resuscitation in the emergency department has been shown to improve outcome.3

Management

Goals in the emergency department within 6 hours:4

MENINGOCOCCAL INFECTION

Management

Prehospital antibiotics in meningococcal sepsis can be life-saving5,6—benzyl penicillin 30 mg/kg up to 1.2 g IM or IV or ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg up to 2 g IM or IV.

Investigations

FEVER

Causes of fever can vary according to:

Pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO)

The decision needs to be made whether the patient requires inpatient or outpatient investigation and management.

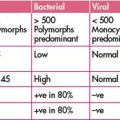

Bacterial meningitis

In adults, 80% are Streptococcus pneumoniae or Neisseria meningitidis.

Clinical features

Of adult patients with bacterial meningitis, 95% present with two of the following:6

Management

Early antibiotics improve outcome.7

Herpes meningo-encephalitis

Request HSV PCR to be performed on CSF.

Malaria

Fever in the overseas traveller is malaria until proven otherwise.

Four plasmodium species cause human malaria—falciparum, vivax, ovale and malariae.

Treatment

Dengue fever (‘break bone fever’)

Typhoid fever

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis A virus

Hepatitis B virus (HBV)

This blood-borne virus is transmitted by parenteral or mucosal exposure to blood or bodily fluids.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)

This blood-borne virus is transmitted predominantly by percutaneous exposure to infected blood. Prevalent in the injecting drug user population. Sexual contact and mother-to-infant transmission is much less common than with hepatitis B infection.

TRAVELlER’s DIARRHOEA

This is commonly caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli.

Usually self-limiting illness and oral rehydration is sufficient management.

Antibiotics are associated with reduction of the duration and severity of the diarrhoea,9 and so can be used if the symptoms are not tolerable.

GASTROENTERITIS

Management

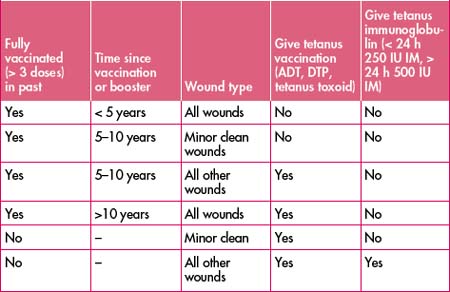

TETANUS

SKIN SEPSIS

(Also see Chapter 40, ‘Dermatological presentations to emergency’.)

Infectious cellulitis

Commonly seen in the leg in adults. Bilateral cellulitis is rare.

Management

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA)

Community-acquired MRSA is becoming more and more prevalent.

Rapidly progressing infections (gangrenous cellulitis)

Necrosis of the soft tissues can spread rapidly and be limb- and life-threatening.

WOUND INFECTIONS

(Also see Chapter 40, ‘Dermatological presentations to emergency’.)

These are usually related to skin organisms and can be managed as for cellulitis.

Remove any foreign material such as sutures and clean/debride as appropriate.

Some special circumstances are included under the following sections.

WATER-RELATED INFECTIONS

These are complicated infections and advice should be sought from your infectious diseases service.

Management

HERPES ZOSTER (SHINGLES)

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTION (STI)

Commencing treatment in emergency department may have important public health benefits.

Presenting complaints include:

Genital lesions

Solitary painless lesion

Vulvovaginitis

Pelvic pain in women

Always exclude pregnancy by testing urine or blood regardless of the history given.

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

Clinical features

URINARY TRACT INFECTION

Asymptomatic bacteriuria need not be treated except in pregnant women.

Uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection (UTI)

Acute pyelonephritis

BODY FLUIDS EXPOSURE AND NEEDLE STICK INJURIES

Follow protocols within your health care facility.

(See also ‘Post-exposure prophylaxis’ in Chapter 42, ‘The immunosuppressed patient’.)

Principles

Hepatitis B

1 Therapeutic guidelines: antibiotic. Version 13. Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2006. Online. Available: http//www.tg.com.au.

2 Nimmo G.R., Coombs G.W., Pearson J.C., et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Australian community: an evolving epidemic. Med J Aust. 2006;184:384-388.

3 Rivers E., et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368-1377.

4 Surviving Sepsis Campaign. International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(1):296-327.

5 Communicable Diseases Network Australia. Guidelines for the early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care; 2001.

6 Hart C.A., Thomson A.P.J. Meningococcal disease and its management in children. BMJ. 2006;333(7570):685-690.

7 Van de Beek D., de Gans J., Tunkel A.R., et al. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:44-53.

8 Halstead S. Dengue. Lancet. 2007;370:1644-1652.

9 De Bruyn G., Hahn S., Borwick A.. Antibiotic treatment for travellers’ diarrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;3:CD002242..

10 Al-Abri S.S., Beeching N.J., Nye F.J. Traveller’s diarrhoea. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(6):349-360.

11 Cox V.C., Zed P.J. Once-daily cefazolin and probenecid for skin and soft tissue infections. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2004;38(3):458-463.

12 Australian Immunisation Handbook. 9th edn. 2008. Online. Available: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/immunise/publishing.nsf/Content/Handbook-home.

13 National guidelines for post-exposure prophylaxis after non-occupational exposure to HIV. Approved March 2007. Commonwealth of Australia. Online. Available: http://www.ashm.org.au/uploads/2007nationalNPEPguidelines2.pdf.