1 Infectious Diseases

Pyrexia of unknown origin (PUO)

Not all cases of PUO are due to infection. In recent-onset PUO, approximately two-thirds of cases are due to infection, compared with only about one-third of cases with long-standing PUO. Other causes include malignancy and autoimmune rheumatic disorders (Table 1.1).

Where would you manage this patient?

Admit to a MAU side room until an infectious aetiology has been ruled out.

What questions should you specifically ask when you see a patient with PUO (in addition to routine questions)?

• Full travel history, including exactly where patient has been and the type of accommodation stayed in

• Vaccination/prophylaxis history

• Contact with animals/sick people

• Occupation: exactly what does the patient do?

• Water exposure: occupational/recreational

• Food history: eating shellfish, drinking dirty water, reheated/raw foods

What initial investigations should you perform in a patient presenting with PUO?

Investigations for a PUO

• Urine analysis and microscopy, culture and sensitivity

• Sputum (if producing any) for microscopy, culture and sensitivity, and for acid-fast bacilli

• Stools for ova, cysts and parasites and culture and sensitivity

• Store serum for future serological tests if required

• Wounds: take swabs for culture

• Screen for autoimmune rheumatic disorders

• Additional investigations in this man because of travel abroad: thick and thin blood films for malaria

What should you do now?

• Recheck his history of travel

• Recheck his risk factors for hepatitis and HIV

The ultrasound shows a liver abscess in the right lobe and, in view of his travel, an amoebic abscess is a strong possibility. Fortunately, you had sent off an amoebic CFT sample and you ring the reference laboratory urgently. The test is positive (usually positive with an amoebic liver abscess).

Treatment

Remember

• Take a careful history: always repeat

• Examine the patient thoroughly: always repeat

• Initial investigations often give a clue to the diagnosis: often need repeating

• Be patient and don’t give antibiotics until diagnosis is made unless the patient is very sick

• Perform invasive and/or expensive investigations only when appropriate, e.g. echo, CT scan/MRI, bone marrow and culture, lymph node/liver biopsy.

Septicaemia

What factors predispose to septicaemia?

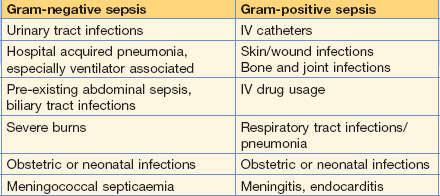

In both Gram-positive and Gram-negative septicaemia, impaired host defences, surgery or instrumentation (including intravenous cannulae, urinary catheters and mechanical ventilation) predispose to septicaemia (Table 1.2).

What would be your initial management of this woman and what investigations would you do?

This patient required supportive therapy (e.g. fluid replacement) because she was dehydrated and oxygen was given and inotropes. Broad-spectrum antibiotics were started after blood and urine cultures had been taken. The antibiotic therapy varies according to local hospital policy and the likely focus of infection. This severely shocked patient was transferred to HDU/ITU (see p. 383).

Investigations

• U&Es, blood sugar, liver biochemistry

• Urine for microscopy, culture and sensitivity

• Sputum (if any produced) for microscopy, culture and sensitivity

• Swabs of any infected-looking lesions (including throat swab if throat appears inflamed)

• Pus (if present) for microscopy, culture and sensitivity

If a urinary tract infection is thought to be the likely source, a broad-spectrum cephalosporin is often appropriate (e.g. cefuroxime) or a quinolone (e.g. ciprofloxacin).

• A broad-spectrum cephalosporin such as IV cefuroxime or IV cefotaxime or IV ceftriaxone.

• Metronidazole should be added if an anaerobic infection is considered likely.

• A broad-spectrum penicillin with β-lactamase inhibitor (e.g. piperacillin/tazobactam). Gentamicin can be added if the patient is very ill.

• A carbapenem (e.g. imipenem, although this is a restricted antibiotic in many hospitals).

Remember

• If you give gentamicin, remember that you need to monitor serum levels. Combining it with a cephalosporin can potentiate its nephrotoxicity.

• Cefuroxime, ceftriaxone and cefotaxime have fairly good activity against staphylococci and streptococci, as well as against many Gram-negative rods; they have poor activity against Pseudomonas spp. Ceftazidime has poor activity against streptococci and staphylococci but excellent activity against Pseudomonas spp. and other Gram-negative organisms. No cephalosporins are active against Enterococcus spp.

• Cephalosporins are associated with C. difficile diarrhoea and should be avoided if possible.

• If a patient develops sepsis while in hospital it is possible that this is due to resistant organisms, e.g. methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or resistant Gram-negative rods.

• If MRSA infection is considered likely and the patient is very sick, add IV vancomycin 1 g × 2 per day (assuming normal renal function) given over at least 100 minutes while awaiting culture results.

A urine sample was obtained from this patient. Microscopy found it to contain 1000 WCC/mm3 and ++ bacteria.

In your hospital, do you know the approximate percentage of organisms causing urinary tract infections that are susceptible to commonly used antibiotics?

Meningococcal meningitis and septicaemia

Case history

The patient was febrile with a temperature of 38°C.

A petechial rash was present (Fig. 1.1).

Contacts who should receive prophylaxis

• People who live in the same household as the case or who have lived there in the previous week

• Work fellows sharing a small office, i.e. an office for two

• Staff carrying out mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on the patient or ‘specialing’ the patient, especially in the first 24 h

Once the CCDC has been informed, he/she will usually arrange for chemoprophylaxis (Table 1.3), but might ask the hospital doctor to do this for the patient’s relatives.

Table 1.3 Recommended chemoprophylaxis of meningococcal meningitis

| First choice | |

| Rifampicin | |

| Adults and children over 12 years | 600 mg × 2 daily for 2 days |

| Children 1–12 years | 10 mg/kg × 2 daily for 2 days (maximum dose 600 mg × 2 daily for 2 days) |

| Infants, 12 months | 5 mg/kg × 2 daily for 2 days |

| Other options | |

| Ciprofloxacin | |

| Adults | 500 mg single dose |

| Children | Not recommended |

| Pregnancy/breastfeeding mothers | Not recommended |

| Ceftriaxone | |

| Adults | 250 mg IM as a single dose |

| Children, 12 years | 125 mg IM as a single dose |

What should you tell people who are taking rifampicin prophylaxis?

• That it might interfere with the effectiveness of the oral contraceptive if they are taking this. Hence they should take additional contraceptive measures for the remainder of the cycle.

• That their secretions (e.g. tears) might turn orangey-pink and that their soft contact lenses will also be permanently stained unless they remove them!

Pseudomembranous colitis

This is the condition caused by Clostridium difficile; a pseudomembrane is seen on sigmoidoscopy.

What other questions do you want to ask?

• What the diarrhoea is like: are the stools liquid or bloody?

• How long has the patient been on broad-spectrum antibiotics?

• Has any other patient/member of the staff got diarrhoea? (One of the ITU nurses informs you that another patient did have loose stools and you need to ascertain if this is really the case and if there were any obvious reasons for this.)

What is your differential diagnosis?

• Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea, particularly pseudomembranous colitis

• Diarrhoea due to enteral feeding

• Other bacterial causes, e.g. Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., E. coli 0157; these are less likely because patient hasn’t been eating but could occur as a result of cross-infection

How would you manage the patient?

Progress.

Remember

Prevention

• Responsible use of antibiotics.

• Hygiene, which should involve all health workers, as well as patients and relatives.

• Washing hands thoroughly using soap and water is essential as alcohol disinfectants do not kill C. difficile spores.

• Hospital cleaning of surfaces should be performed regularly to try and reduce transmission from fomites.

Food poisoning: E. coli 0157

What is the differential diagnosis in this patient?

Typhoid

What is the most likely diagnosis?

S. typhi (this was later confirmed as being the definitive diagnosis).

The returning traveller

What further questions do you want to ask this man?

Differential diagnosis is shown in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4 Causes of febrile illness in travellers returning from the tropics and world-wide

| Developing countries | Specific geographical areas (see text) |

| Malaria | Histoplasmosis |

| Schistosomiasis | Brucellosis |

| Dengue | World-wide |

| Tick typhus | Influenza |

| Typhoid | Pneumonia |

| Tuberculosis | URTI |

| Dysentery | UTI |

| Hepatitis A | Traveller’s diarrhoea |

| Amoebiasis | Viral infection Sexually transmitted diseases |

WHO advises that fever occurring in a traveller 1 week or more after entering a malaria risk area and up to 3 months after departure is a medical emergency.

URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; UTI, urinary tract infection.

Shingles

Varicella zoster virus causes a primary infection – chickenpox, usually in children.