2 Infectious disease

Approach to the patient with a suspected infection

• Management

Returning travellers (Table 2.1)

There are number of common illnesses that occur only in certain areas. The history should cover all recent travel. Most tropical illnesses are uncommon in the countries in which they occur; upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections and viral infections are still common worldwide. However, some illnesses, such as malaria or dengue, are common. WHO advises that fever occurring in a traveller 1 week or more after entering a malaria risk area and up to 3 months after departure is a medical emergency because of the mortality associated with Plasmodium falciparum, though there have been well-reported cases of falciparum infection occurring after 3 months. Viral haemorrhagic fevers are also seen in patients returning from endemic areas, though these are very rare infections. Websites are a useful source of up-to-date information on geographic medicine and epidemics (e.g. www.cdc.gov/travel/destinat.htm).

Table 2.1 Causes of febrile illness in travellers returning from the Tropics and world-wide

| Developing countries | Specific geographical areas (see text) |

|---|---|

| Malaria | Histoplasmosis |

| Schistosomiasis | Brucellosis |

| Dengue | World-wide |

| Tick typhus | Influenza |

| Typhoid | Pneumonia |

| Tuberculosis | Upper respiratory tract infection |

| Dysentery | Urinary tract infection |

| Hepatitis A | Traveller’s diarrhea |

| Amoebiasis | Viral infection |

Fever of unknown origin (FUO)

Systemic multi-system infections

Sepsis

Management

Sepsis and septic shock should be treated urgently, as should the bacterial cause of the infection.

Meningococcal septicaemia

Presentation is with the classic triad of headache, fever and neck stiffness, though this is not always the case (p. 54). Septicaemia causes septic shock with fever, myalgia and hypotension, and may be accompanied by a petechial or haemorrhagic rash. The case fatality rate is approximately 10%.

Management (Box 2.1)

Start antibiotics immediately.

Box 2.1 Meningococcal meningitis and meningococcaemia emergency treatment

Suspicion of meningococcal infection is a medical emergency requiring treatment immediately

Malaria

Diagnosis

Management of uncomplicated falciparum malaria

The treatment of malaria varies, depending on the resistance patterns to antimalarial chemotherapy and will vary over time. Up-to-date advice should be sought if there are doubts as to the appropriate therapy. There is very little chloroquine-sensitive falciparum malaria. Treatments for uncomplicated falciparum malaria are shown in Table 2.2.

| Type of malaria | Drug treatment |

|---|---|

| Plasmodium vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae | Chloroquine 600 mg 300 mg 6 hours later 300 mg 24 hours later 300 mg 24 hours later |

| P. falciparum (almost all are resistant to chloroquine) | Quinine 600 mg 3 times daily for 7 days Plus Doxycycline 200 mg once daily for 7 days Or Clindamycin 450 mg 3 times daily for 7 days (Fansidar (SP) (pyrimethamine and sulfadoxine) 3 tablets as single dose with or following quinine) Or Malarone 4 tablets daily for 3 days Or Riamet (artemether with lumefantrine) 4 tablets 12-hourly for 3 days |

| Alternative therapy | |

| Artesunate-mefloquine 12/25 mg/kg daily for 3 days Or Dihydroartemisinin/piperaquine 6.3 mg/kg daily for 3 days |

Management of severe falciparum malaria (Box 2.2)

Management of non-falciparum malaria

Non-falciparum malarias can be treated with oral chloroquine 600 mg, then 300 mg after 8 hours, then 300 mg daily for 2 days. There is some reported chloroquine-resistant malaria in Papua New Guinea and treatment can be with riamet or malarone (dosages in Table 2.2). P. vivax and P. ovale have hypnozoites that may persist and cause a recurrence of infection many years later. Patients with vivax or ovale infection should receive primaquine 15 mg daily for 2–3 weeks following successful treatment, to eradicate hepatic hypnozoites and prevent relapse. Anyone who is about to receive primaquine should have their glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) status checked, as primaquine use is associated with haemolysis in patients with G6PD deficiency (p. 216). WHO guidelines www.who.int/topics/malaria/en.

Prevention of malaria

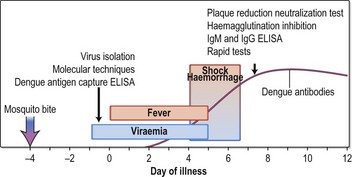

Dengue

Plague

Clinical features

Clinical manifestations of plague are bubonic, septicaemic, pneumonic, pharyngeal and meningitis.

Brucellosis

Clinical features

The onset is insidious, with an incubation period about 2–4 weeks. Symptoms are initially non-specific, although specific ones include an ‘undulant’ fever, malodorous sweat and a peculiar taste in the mouth. Brucellosis can affect nearly any organ of the body and includes lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, sacro-iliitis, arthritis, osteomyelitis and meningoencephalitis. Chronic brucellosis can last over a year. Symptoms may also recur over long periods.

Investigations

Listeriosis

Clinical features

Q fever

Infection with the obligate intracellular pathogen Coxiella burnetii, which is widespread in many animals, is the cause of Q fever. Transmission to humans is usually via dust, aerosol and unpasteurized milk; spore formation means that the infection can remain in the environment for long periods.

Lyme disease

There are three stages of Lyme infection:

Treatment

Visceral leishmaniasis

Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) is caused by Leishmania donovani, L. infantum or L. chagasi, and is present in India, Asia, Africa, the Mediterranean and South America. In central India, humans are the main host and the disease occurs in epidemics. In most other areas, it is a zoonosis; the main animal reservoirs are dogs and foxes, although in Africa it is carried by rodents. Visceral leishmaniasis is a common opportunistic infection of advanced HIV disease in Mediterranean coastal regions.

Diagnosis

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)

Clinical features

Skin and soft-tissue infections

Meticillin-resistant Staph. aureus (MRSA)

Treatment

Treatment of MRSA infection depends on the source of the infection and the sensitivity of the MRSA.

Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome (TSS)

In the early 1980s, most cases of TSS were in menstruating females and associated with retained tampons. Recently, TSS has been less often associated with menstruation.

Post-streptococcal syndromes

Rheumatic fever

• Treatment

Other post-streptococcal syndromes

Necrotising skin and soft-tissue infections

Bite wounds

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) infection

Shingles is a secondary reactivation of latent VZV infection in the distribution of one or sometimes two dermatomes. The vesicles of shingles are identical to those in chickenpox. Shingles mainly affects the elderly but can occur at any age. Post-herpetic neuralgia may occur after herpes infection and causes severe debilitating pain. Shingles involving the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve has a high rate of complications. Disseminated shingles infection can occur in the immunosuppressed patients (particularly in late HIV infection), when the rash is seen over many dermatomes and appears similar to chickenpox. Shingles lesions may transmit infection to non-immune individuals.

Treatment

Respiratory infections

Upper respiratory tract infections

Pharyngitis

Epiglottitis

Sinusitis

Otitis media

Diphtheria

Lower respiratory tract infections

Influenza

Pertussis (whooping cough)

Lung abscess

• Investigations

Cardiological infections

Infective endocarditis (IE)

Diagnosis

The Duke Criteria are the established way of making the diagnosis clinically.

Pericarditis

Non-infective pericarditis occurs following a myocardial infarct (p. 445), in malignant disease (lung cancer, lymphoma), in uraemia and after surgery.

Neurological infections

Meningitis

Clinical features

Investigations

In bacterial meningitis there is usually a neutrophilia and a raised CRP.

Treatment

Other forms of meningitis

Rabies

Tetanus

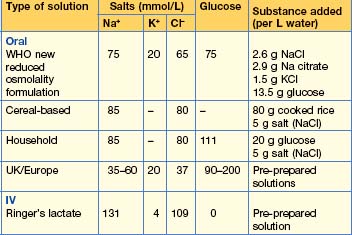

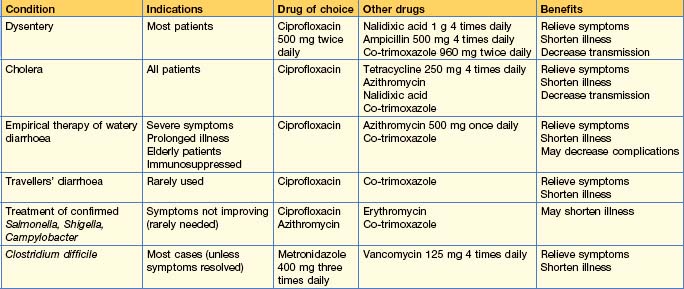

Gastrointestinal infections

Gastroenteritis (see also p. 135)

Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea

Gastrointestinal tuberculosis

Peritonitis

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

The yearly risk of developing spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) for patients with ascites and cirrhosis has been estimated to be as high as 29%. See Chapter 6 (p. 189) for Diagnosis and Treatment.

Peritonitis secondary to large bowel perforation, ruptured appendix or ruptured diverticulum

Peritonitis with continuous peritoneal dialysis (CAPD)

Tuberculous peritonitis

This is the second most common form of abdominal TB.

Hepatobiliary and pancreatic infections

Liver abscess (see also p. 194)

Treatment

Genitourinary infections

Systemic fungal infections

Candidiasis

Histoplasmosis

Clinical features

Aspergillosis

Cryptococcosis

Coccidioidomycosis

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis and is found in North America.

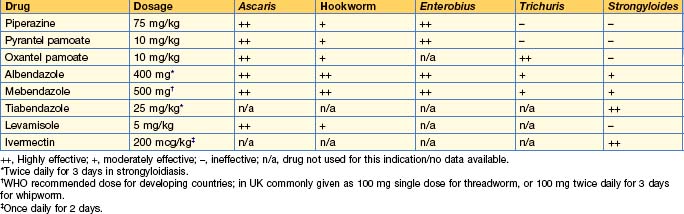

Helminthic infections

Worm infections are very common in developing countries. Multiple infections with different helminths are common in endemic areas. Mass treatment programmes are carried out, usually annually, to keep the total worm load down (see Table 2.5). Treatment of trematodes and intestinal nematodes is shown in Tables 2.6 and 2.7 respectively.

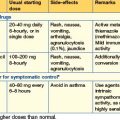

Table 2.5 Drugs used in mass treatment programmes for helminth infections (alone or in combination)

| Drug | Infection |

|---|---|

| Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) | Loiasis |

| Filariasis | |

| Ivermectin | Loiasis |

| Filariasis | |

| Onchocerciasis | |

| Strongyloidiasis | |

| Albendazole | Filariasis (with DEC) |

| Intestinal helminths | |

| Praziquantel | Schistosomiasis |

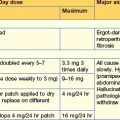

Table 2.6 Treatment of trematode infections

| Parasite | Drug and dose |

|---|---|

| Schistosoma mansoni | Praziquantel 40 mg/kg single dose* |

| S. haematobium | Praziquantel 40 mg/kg single dose* |

| S. japonicum | Praziquantel 60 mg/kg single dose* |

| Paragonimus spp. | Praziquantel 25 mg/kg 8-hourly for 3 days |

| Chlonorchis sinensis | Praziquantel 25 mg/kg 8-hourly for 2 days |

| Opisthorcis spp. | Praziquantel 25 mg/kg 8-hourly for 1 day |

| Fasciolopsis buski | Praziquantel 25 mg/kg 8-hourly for 1 day |

| Fasciola hepatica | Triclabendazole 10 mg/kg single dose† |

Sexually transmitted infections

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are very common worldwide.

Syphilis

Treatment

Chancroid

Trichomoniasis

Gonorrhoea

Antimicrobial drugs

General principles of use

Antimicrobial prophylaxis

Situations in which prophylaxis is needed include the following:

Adverse effects

Antibacterial drugs

β-lactams

Penicillins

Penicillin is active against streptococci, including most pneumococci, meningococci, Corynebacterium diphtheriae and treponemes. Most strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are now resistant because of the production of β-lactamase. IM preparations, e.g. benzyl penicillin, procaine penicillin and the derivatives of benzyl penicillin, such as benthamine penicillin or benzathine penicillin, are less frequently used but are still useful in the treatment of syphilis (p. 72).

Cephalosporins

Carbapenems

Aminoglycosides

Side-effects: aminoglycosides are nephrotoxic and therapeutic drug monitoring is essential (p. 365). Nephrotoxicity is reversible if detected early but permanent damage can occur. Use cautiously in liver disease. Ototoxicity can be vestibular or due to cochlear damage. Aminoglycosides should not be used along with ototoxic diuretics, e.g. furosemide.

Macrolides

Glycopeptides

Glycopeptides interfere with bacterial cell wall synthesis and are bactericidal.

Tetracyclines

Quinolones

Sulphonamides and trimethoprim

Nitroimidazoles

Chloramphenicol

Side-effects can be serious and include irreversible aplastic anaemia, limiting its use. Gastrointestinal (nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea) and neurological (peripheral neuropathy, optic neuritis, headaches, depression) side-effects occur.

Other antibiotics

Antituberculosis drugs

These agents are always used in combination to prevent development of resistance. Four drugs for 2 months (after which the sensitivities are available) and two drugs for a further 4 months is the standard regimen for unsupervised treatment. Formulations comprising combinations of these drugs are available. See p. 87 for details of all treatments for TB and infections with non-tuberculous mycobacteria.

Antileprotic drugs

Antifungal agents

Polyenes

Azoles

Imidazoles

This group of agents has a broad range of antifungal activity.

Triazoles

Echinocandins

The echinocandins inhibit the synthesis of glucan, a constituent of the fungal cell wall.

Other antifungals

Antiviral agents

Drugs used for herpes virus infections

Drugs used for influenza

Drugs used for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

Side-effects: for ribavirin, see p. 186. Palivizumab can cause injection site reactions, fever, rash, nervousness and gastrointestinal problems.

Other antivirals

Antiprotozoal agents

Antimalarial agents (p. 35)

Other antiprotozoal agents

Antihelminthic agents

http://BNF.org. British National Formulary

www.brit-thoracic.org.uk. British Thoracic Society

www.hpa.org.uk/infections/topics_az/antimicrobial_resistance/guidance.htm. Health Protection Agency

www.idsociety.org. Infectious Disease Society of America

www.nice.org.uk. NICE guidelines

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi. Online Microbiology textbook

www.sanfordguide.com/. Sanford Guide