Chapter 38 Infectious Disease Emergencies

FEVER

1 A 10-day-old, full-term male infant presents to the emergency department (ED) with a 1-day history of being fussy but consolable, slightly decreased oral intake, and a temperature of 38.5° C rectally. What is the risk for serious bacterial illness?

2 Which bacterial agents are of most concern in an infant < 28 days old presenting to the ED with a fever?

3 A 26-day-old infant presents to the ED with a 1-day history of fever up to 39° C rectally. What should your initial management include?

Perform a complete history (including prenatal history) and physical examination of the newborn.

Perform a complete history (including prenatal history) and physical examination of the newborn.

Obtain laboratory studies, including a complete blood count (CBC) with differential and blood culture; urine obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration for urinalysis, Gram stain, and culture; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for protein/glucose, cell count, Gram stain, and bacterial/viral cultures; chest radiograph if signs of respiratory distress (tachypnea, cyanosis, wheezing, retractions, grunting, nasal flaring, rales, rhonchi, or decreased breath sounds); and stool for heme testing and culture if bloody or watery stool is noted.

Obtain laboratory studies, including a complete blood count (CBC) with differential and blood culture; urine obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration for urinalysis, Gram stain, and culture; cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for protein/glucose, cell count, Gram stain, and bacterial/viral cultures; chest radiograph if signs of respiratory distress (tachypnea, cyanosis, wheezing, retractions, grunting, nasal flaring, rales, rhonchi, or decreased breath sounds); and stool for heme testing and culture if bloody or watery stool is noted.

Admit patient to the hospital and administer parenteral antibiotics (ampicillin plus cefotaxime or gentamycin).

Admit patient to the hospital and administer parenteral antibiotics (ampicillin plus cefotaxime or gentamycin).

Consider IV acyclovir if neonatal herpes is suggested by history or physical examination.

Consider IV acyclovir if neonatal herpes is suggested by history or physical examination.

5 A 6-week-old male infant presents to the ED with a temperature of 38.4° C. The infant appears nontoxic and is without an obvious source for the fever. How likely is this infant to have a bacterial infection?

6 What is the cause of a temperature of 38.0° C in infants age 1–3 months who present to the ED?

A published study of 422 such infants determined the following sources:

7 A 2-month-old presents with a temperature of 40.5° C and otherwise appears nontoxic. Do infants with hyperpyrexia have a higher risk of having a serious bacterial infection?

8 What is the most common cause of sepsis in newborns?

Early-onset (birth to 7 days) group B streptococcal (GBS) infections, which may be secondary to maternal obstetric complications, prematurity, or lack of prophylactic antibiotics prior to delivery. Late-onset GBS infection (7 days to 3 months) is uncommonly associated with these factors (Table 38-1).

TABLE 38-1 EARLY-ONSET VERSUS LATE-ONSET GROUP B STREPTOCOCCAL INFECTIONS

| Type of GBS | Usual Clinical Presentations | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Early-onset GBS | Septicemia (25–40%) | 5–20% mortality |

| Meningitis (5–15%) | ||

| Respiratory illness (35–55%) | ||

| Late-onset GBS | Meningitis (30–40%) | 2–6% mortality |

| Bacteremia without focus (40–50%) | ||

| Osteomyelitis/septic arthritis (5–10%) |

GBS = group B streptococcus.

9 Does the immature neutrophil (band) count help in distinguishing bacterial infections from viral infections in infants age 3–36 months presenting to the ED with a temperature > 39.0° C?

10 Has the introduction of the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) affected the incidence of occult bacteremia?

OPHTHALMIC INFECTIONS

14 Distinguish between the presentation of preseptal and orbital cellulitis in children.

| Feature | Preseptal Cellulitis | Orbital Cellulitis |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Infection of the eyelids anterior to the orbital septum | Infectious process posterior to the orbital septum involving the tissues within the orbit (eye, fat, muscles, optic nerve) |

| Etiology |

+ indicates present, − indicates absent.

15 How should a patient with suspected orbital cellulitis be managed?

WBC count (often reveals leukocytosis with predominance of bands)

WBC count (often reveals leukocytosis with predominance of bands)

Blood cultures obtained before antibiotics

Blood cultures obtained before antibiotics

Orbital computed tomography (CT) with thin and coronal cuts, including frontal lobes

Orbital computed tomography (CT) with thin and coronal cuts, including frontal lobes

Lumbar puncture if meningeal signs are present (only after negative findings on CT of the head for signs of increased intracranial pressure)

Lumbar puncture if meningeal signs are present (only after negative findings on CT of the head for signs of increased intracranial pressure)

Admission to the hospital for IV antibiotics (IV ceftriaxone or cefotaxime)

Admission to the hospital for IV antibiotics (IV ceftriaxone or cefotaxime)

Consultation with ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology, or infectious diseases, as necessary

Consultation with ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology, or infectious diseases, as necessary

16 What are the indications for hospital admission of infants and children who present with preseptal cellulitis?

17 For children discharged from the ED with the diagnosis of preseptal cellulitis, which antibiotics are best?

19 Distinguish between conjunctivitis caused by C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae.

TABLE 38-3 CHLAMYDIA TRACHOMATIS VS. NEISSERIA GONORRHOEAE CONJUNCTIVITIS

| Features | Chlamydia trachomatis | Neisseria gonorrhoeae |

|---|---|---|

| Presentation | First 3 weeks of life | 24–48 hours after birth |

| Distinctive clinical features | Initially serous then muco-purulent discharge Unilateral or bilateral |

Acute onset of purulent conjunctival discharge, marked eyelid edema, and chemosis Septicemia, meningitis, or arthritis |

| Potential complications | Self-limited Rarely conjunctival or corneal-scarring Potential development of upper and lower respiratory tract infections |

Potential corneal ulceration and perforation |

| Treatment | Oral erythromycin estolatesyrup for 2 weeks plustopical erythromycin four times a day | Parenteral ceftriaxone or cefotaxime, penicillin G,penicillin G topical |

20 A 5-year-old girl presents to the ED with “burning and itchy” eyes. She describes a sensation of “chalk in her eyes,” with some blurry vision. On physical examination, she has bilateral conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, and ocular discharge, and has preauricular lymph nodes bilaterally. What is the differential diagnosis?

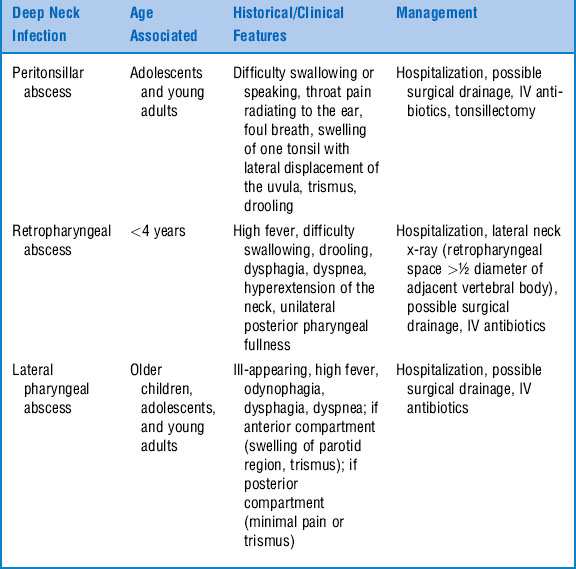

NECK INFECTIONS

22 What organisms are associated with deep neck infections (peritonsillar abscess, retropharyngeal abscess, and lateral pharyngeal abscess) in children?

EAR, NOSE, AND THROAT INFECTIONS

26 A 3-year-old boy with a history of mild to moderate eczema presents to the ED with ear pain and drainage. On physical examination, his tympanic membrane appears normal, although swelling of the ear canal makes it difficult to view the entire tympanic membrane. There is pain on movement of the tragus. There is no lateral displacement of the ear and no signs of mastoiditis. What is the likely diagnosis?

29 List the three major causes of exudative pharyngitis in children.

Exudate refers to white or gray debris on the tonsils or pharynx. Causes include:

30 A 7-year-old has fever, sore throat, tender anterior cervical lymph nodes, and lack of significant upper respiratory tract symptoms. Are these clinical features suggestive of GABHS pharyngitis?

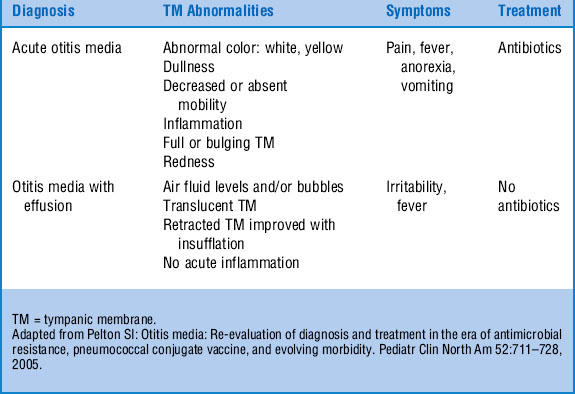

32 How is the diagnosis of otitis media made?

Otitis media is diagnosed as an acute otitis media or otitis media with effusion. See Table 38-5.

33 Which pathogens are implicated in acute otitis media?

38 You decide to intubate the trachea of a young patient who presents with severe respiratory distress and stridor. On endotracheal intubation, purulent tracheal secretions are seen. What is the likely diagnosis?

39 What are the common causes of stomatitis? How can they be distinguished?

41 What are the typical organisms causing sinusitis?

The typical organisms associated with acute sinusitis include:

42 What criteria define sinusitis?

Acute bacterial sinusitis is an infection of the paranasal sinuses lasting less than 30 days that presents with either persistent or severe symptoms.

Acute bacterial sinusitis is an infection of the paranasal sinuses lasting less than 30 days that presents with either persistent or severe symptoms.

Persistent symptoms are those that last longer than 10–14, but less than 30, days and include nasal or postnasal discharge (of any quality), daytime cough (which may be worse at night), or both.

Persistent symptoms are those that last longer than 10–14, but less than 30, days and include nasal or postnasal discharge (of any quality), daytime cough (which may be worse at night), or both.

Severe symptoms include a temperature of at least 102°F and purulent nasal discharge present concurrently for at least 3–4 consecutive days in a child who seems ill.

Severe symptoms include a temperature of at least 102°F and purulent nasal discharge present concurrently for at least 3–4 consecutive days in a child who seems ill.

44 When is imaging necessary in the diagnosis of acute bacterial sinusitis?

Wald ER: Clinical features, diagnosis, and evaluation of acute bacterial sinusitis in children, 2006: www.uptodate.com

45 When is CT useful in the diagnosis of sinusitis?

CT (Fig. 38-1) is helpful in children with complications of acute bacterial sinus infection or those with very persistent or recurrent infections that do not respond to medical management.

46 Describe the treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis.

1 For uncomplicated acute bacterial sinusitis of mild to moderate severity:

2 For children with acute bacterial sinusitis of at least moderate severity or who have received an antibiotic in the past 90 days or who attend day care:

3 Children with vomiting can be treated with one dose of IV ceftriaxone followed by oral antibiotics after vomiting has subsided.

Wald ER: Microbiology and treatment of acute bacterial sinusitis, 2006: www.uptodate.com

47 What is Pott’s puffy tumor?

Pott’s puffy tumor (Fig. 38-2) was first described by Sir Percivall Pott in 1760, and appears as a soft, fluctuant, painful forehead or scalp swelling usually associated with frontal sinusitis. Patients tend to be febrile and appear toxic. It is usually seen in children after 8 years of age when the frontal sinuses begin to develop. It represents osteomyelitis of the frontal bone with subsequent subperiosteal elevation. CT is essential for diagnosis and to evaluate other possible areas of spread. Successful treatment usually involves both antibiotics and surgical drainage.

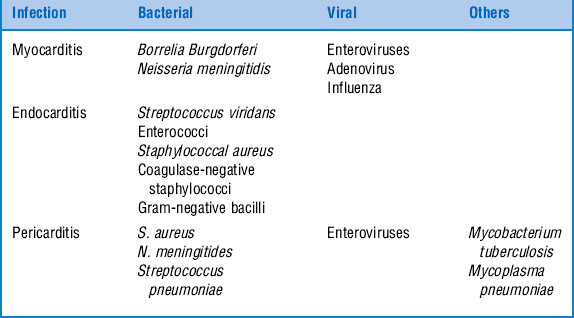

CARDIAC INFECTIONS

50 What diagnostic test results in the ED support the suspicion of myocarditis?

Chest radiography can demonstrate cardiomegaly, interstitial pulmonary edema, or an engorged pulmonary venous pattern.

Chest radiography can demonstrate cardiomegaly, interstitial pulmonary edema, or an engorged pulmonary venous pattern.

Electrocardiography may demonstrate mild to moderate PR interval prolongation, generalized low-voltage QRS complexes, ST-segment elevation or depression, decreased precordial voltages, high-grade atrioventricular block, and complex ventricular arrhythmias.

Electrocardiography may demonstrate mild to moderate PR interval prolongation, generalized low-voltage QRS complexes, ST-segment elevation or depression, decreased precordial voltages, high-grade atrioventricular block, and complex ventricular arrhythmias.

Echocardiography typically demonstrates global cardiac chamber enlargement with poorly contracting ventricles or atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

Echocardiography typically demonstrates global cardiac chamber enlargement with poorly contracting ventricles or atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

WBC count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and creatine kinase–MB fraction may be abnormal but are nonspecific.

WBC count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and creatine kinase–MB fraction may be abnormal but are nonspecific.

51 What is the acute management of myocarditis in infants and children?

52 What are the common symptoms, signs, and laboratory findings in infants and children with infective endocarditis?

TABLE 38-7 SYMPTOMS, SIGNS, AND LABORATORY FINDINGS IN INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

| Symptoms | Signs | Laboratory Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Fever | Fever | Positive blood culture (75–100%) |

| Malaise | Petechiae | Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (75–100%) |

| Anorexia/weight loss | Splenomegaly | Anemia (75–90%) |

| Arthralgias | New or changed murmur | |

| Less frequent | ||

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | Embolic phenomenon | Hematuria (25–50%) |

| Neurologic deficits | Heart failure | Positive rheumatoid factor (25–50%) |

| Aseptic meningitis | Low complement level (5–40%) | |

| Chest pain |

53 Differentiate among Osler nodes, Janeway lesions, and Roth spots.

56 What are the clinical manifestations and diagnostic findings associated with pericarditis?

Pericardial friction rub during deep inspiration with the patient kneeling or in the knee-chest position

Pericardial friction rub during deep inspiration with the patient kneeling or in the knee-chest position

If tamponade: tachycardia, peripheral vasoconstriction, decreased arterial pulse pressure, or pulsus paradoxus

If tamponade: tachycardia, peripheral vasoconstriction, decreased arterial pulse pressure, or pulsus paradoxus

Pericardial fluid analysis suggestive of infection

Pericardial fluid analysis suggestive of infection

Increased size of cardiac shadow in the absence of pulmonary congestion on chest radiography (“water bottle heart”)

Increased size of cardiac shadow in the absence of pulmonary congestion on chest radiography (“water bottle heart”)

Electrocardiography: ST-segment elevations without reciprocal ST-segment depression, except in leads V1 and aVR; flattening or inversion of T waves (late), low-voltage QRS waves

Electrocardiography: ST-segment elevations without reciprocal ST-segment depression, except in leads V1 and aVR; flattening or inversion of T waves (late), low-voltage QRS waves

Echocardiography: presence of pericardial fluid

Echocardiography: presence of pericardial fluid

Microbiological evaluation of the pericardial fluid by pericardiocentesis

Microbiological evaluation of the pericardial fluid by pericardiocentesis

Viral cultures, serologic tests, and molecular genetic techniques

Viral cultures, serologic tests, and molecular genetic techniques

URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

59 What are the signs and symptoms of UTIs in infants and children?

See Table 38-8. Approximately 50% of adolescents who present to the ED with dysuria, increased frequency, and urgency on urination have a UTI. Only 10% of children who present with these symptoms have a UTI; their symptoms may instead be due to bubble bath irritation, vaginitis, pinworms, or sexual abuse.

TABLE 38-8 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS ACCORDING TO AGE

| Newborns | Infants and Toddlers | School-Age Children |

|---|---|---|

| Fever | Fever | Fever |

| Hypothermia | Failure to thrive | Vomiting |

| Vomiting | Vomiting | Diarrhea |

| Failure to thrive | Diarrhea | Strong-smelling urine |

| Sepsis | Strong-smelling urine | Abdominal pain |

| Jaundice | Irritability | Dysuria |

| Irritability | Frequency | |

| Urgency | ||

| Enuresis |

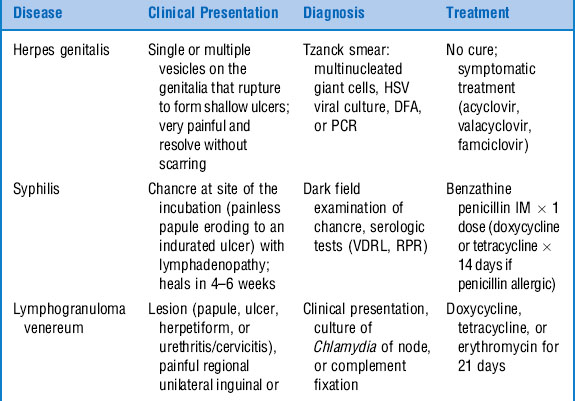

GYNECOLOGIC INFECTIONS

67 What is the etiology of vaginitis in postpubertal girls? What characteristics distinguish the infections?

Patients with vaginitis typically present with a history of dysuria, vaginal discharge, burning, or vulvar lesions. Physical examination reveals vulvar irritation and vaginal discharge. The infectious etiologies in postpubertal girls include bacterial vaginosis (40–50%), vulvovaginal candidiasis (20–25%), and Trichomonas vaginitis (15–20%) (Table 38-9).

CELLULITIS

70 Are cultures helpful in diagnosing cellulitis?

Sadow KB: Blood cultures in the evaluation of children with cellulitis. Pediatrics 101:e4, 1998.

72 A 9-year-old child presents to the ED with a chief complaint of right foot pain. Four days ago he stepped on a nail that went through his sneaker into his sole. He presents with no history of fever, but with erythema and warmth of the sole of his foot and point tenderness at the proximal end of his fifth metatarsal. What diagnosis do you suspect?

74 Match the superficial bacterial skin infection with its classical presentation and treatment.

| 1. May begin following minor trauma or an insect bite; initially vesiculopapular with surrounding erythema and later developing a thick, adherent crust that, when removed, reveals a punched out, painful ulcerative lesion. Treatment includes cleansing, and topical and systemic antibiotics covering streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus. Typically seen in immunocompromised patients. | A. Impetigo B. Ecthyma C. Erysipelas D. Paronychia E. Folliculitis F. Furuncles/carbuncles |

| 2. Results from local injury to the nail fold seen in children who suck their fingers or bite their nails; lateral nail fold becomes warm, erythematous, edematous, and painful. Treatment includes warm compresses and, for deep infections, incision and drainage and antibiotics covering mixed oral flora. | |

| 3. Either isolated nodular subcutaneous abscesses or multiple abscesses separated by connective tissue septae clinically presenting as painful red papules or boils in a nontoxic-appearing child. Treatment includes local care, incision and drainage, and systemic antibiotics for larger lesions. | |

| 4. Superficial infection of the skin caused by either Staphylococcus aureus or GABHS appearing as mildly painful lesions with an erythematous base and honey-crusted exudates in a nontoxic child; absence of constitutional symptoms and presence of regional adenopathy. Treatment includes topical mupirocin or systemic antibiotics (widespread lesions, lesions near the mouth, evidence of deeper infection, constitutional symptoms). | |

| 5. Clearly demarcated, raised, and advancing red border extending from the site of inoculation with lymphangitic streaks extending from the involved area; shiny and warm to touch; presence of systemic signs and high fever. Treatment with IV antibiotics until patient is afebrile and lesion begins to regress, then oral antibiotics. | |

| 6. Small, red pustules at the site of hair follicles. Treatment includes local care and topical antibiotics. |

75 A 4-year-old presents with a boggy, purulent, eczematoid mass measuring 5 × 5 cm on his right temporal scalp area. He also has alopecia and a right-sided, posterior chain cervical adenopathy. What is the likely diagnosis?

76 What findings may be associated with an invasive skin or soft tissue infection?

Necrosis of skin or soft tissue

Necrosis of skin or soft tissue

Crepitance on physical examination

Crepitance on physical examination

Nonadherence of skin and subcutaneous tissue to underlying fascia on exploration

Nonadherence of skin and subcutaneous tissue to underlying fascia on exploration

Abnormal skin color other than erythema (such as bronzed, cyanotic, violaceous)

Abnormal skin color other than erythema (such as bronzed, cyanotic, violaceous)

Severe systemic toxicity, anxiety, or confusion

Severe systemic toxicity, anxiety, or confusion

Pain on palpation out of proportion to physical findings

Pain on palpation out of proportion to physical findings

Tachycardia out of proportion to fever (suggestive of clostridial infection)

Tachycardia out of proportion to fever (suggestive of clostridial infection)

Hypocalcemia (calcium deposition in necrotic subcutaneous fat)

Hypocalcemia (calcium deposition in necrotic subcutaneous fat)

Failure to respond to medical management

Failure to respond to medical management

Bullae with thin, brown discharge with “sweet but foul” odor (clostridial infection), or “dishwater” fluid (anaerobic fluid)

Bullae with thin, brown discharge with “sweet but foul” odor (clostridial infection), or “dishwater” fluid (anaerobic fluid)

LYMPH NODES

78 Lymphadenopathy isolated to a particular region may indicate a specific infection. List some of these associations

TABLE 38-11 REGIONAL LYMPHADENOPATHY AND ASSOCIATED INFECTIOUS ETIOLOGY

| Infectious Etiology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Region | Common | Less Common |

| Occipital | Impetigo Tinea capitis Seborrhea |

Toxoplasmosis Rubella |

| Preauricular | Pediculosis Chlamydial conjunctivitis Adenoviral conjunctivitis |

Tularemia Herpes simplex Parinaud’s syndrome |

| Cervical | Viral upper respiratory tract infection Bacterial infection of head/neck Primary bacterial adenitis Epstein-Barr virus/cytomegalovirus Cat scratch disease Atypical mycobacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis |

Kawasaki disease Toxoplasmosis Anaerobic infection Tularemia Histoplasmosis Leptospirosis Brucellosis |

| Axillary | Local pyogenic infection Cat scratch disease |

Toxoplasmosis |

| Epitrochlear | Local infection Chronically inflamed hand |

Secondary syphilis Tularemia |

| Inguinal | Lower-extremity infection Genital herpes Primary syphilis |

Chancroid Lymphogranuloma venereum |

| Iliac | Lower-extremity infection Abdominal infection Urinary tract infection |

|

| Popliteal | Severe local pyogenic infection | |

79 How does a child with cat scratch disease typically present?

Spach DH, Myers SA, Kaplan SL: Cat scratch disease, 2006: www.uptodate.com

80 What are atypical clinical manifestations seen in cat scratch disease (5–20% of all presentations)?

Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome (conjunctival granuloma and preauricular adenopathy)

Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome (conjunctival granuloma and preauricular adenopathy)

Osteitis resembling bacterial osteomyelitis

Osteitis resembling bacterial osteomyelitis

Central nervous system (CNS) manifestations (encephalopathy, encephalitis, radiculitis, polyneuritis, myelitis, neuroretinitis)

Central nervous system (CNS) manifestations (encephalopathy, encephalitis, radiculitis, polyneuritis, myelitis, neuroretinitis)

In immunocompromised children, bacteremia, bacillary angiomatosis, and bacillary peliosis

In immunocompromised children, bacteremia, bacillary angiomatosis, and bacillary peliosis

SEPSIS

82 Distinguish among bacteremia, systemic inflammation response syndrome (SIRS), sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock.

Bacteremia: The presence of bacteria in the blood

SIRS: A clinical syndrome in response to a variety of insults (e.g., infection, trauma, acute respiratory distress syndrome, neoplasms, pancreatitis, burns) manifested by at least two of the following conditions:

Tachypnea (respiratory rate > 60 breaths per minute in infants, > 50 breaths per minute in children)

Tachypnea (respiratory rate > 60 breaths per minute in infants, > 50 breaths per minute in children)Sepsis: The systemic response to infections manifested by two or more of the criteria for SIRS

Severe sepsis: Sepsis associated with hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 65 mmHg in infants, < 75 mmHg in children, and < 90 mmHg in adolescents, or reduction > 40 mmHg from baseline), hypoperfusion (lactic acidosis, oliguria, hypoxemia, or acute change in mental status), or organ dysfunction

Septic shock: Sepsis with hypotension, despite adequate fluid resuscitation, with the presence of perfusion abnormalities, which may include lactic acidosis, oliguria, or acute change in mental status.

83 What are the common signs/symptoms and laboratory values associated with septic shock in infants and children?

| Signs/Symptoms | Laboratory Results |

|---|---|

| Hyperthermia or hypothermia | Lactic acidosis |

| Tachycardia | Leukocytosis or leukopenia |

| Tachypnea | Increased bands, myelocytes, promyelocytes |

| Signs/Symptoms | Laboratory Results |

|---|---|

| Hypotension | High or low serum glucose level |

| Delayed capillary refill | Hypocalcemia |

| Weak peripheral pulses | Hypoalbuminemia |

| Cool extremities | Positive blood, urine, CSF cultures |

| Irritability | Abnormal coagulation factors/disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| Lethargy | Thrombocytopenia |

| Confusion | Abnormal renal function |

| Oliguria | |

| Petechiae or purpura |

84 What are the antibiotic choices for empirical therapy in infants and children presenting in septic shock?

TABLE 38-12 EMPIRICAL THERAPY FOR SEPTIC SHOCK ACCORDING TO AGE

| Age/Condition | Bacterial Etiology | Antibiotic Choice for Empirical Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Neonate | GBS | Ampicillin plus aminoglycoside or cefotaxime; if nosocomial, then add vancomycin |

| Gram-negative bacilli | Cefotaxime or ceftriaxone plus vancomycin (if you suspect gram-positive infection) | |

| Child | S. pneumoniae, N. meningitidis, S. aureus, GAS | If nosocomial, vancomycin plus antibioticagainst gram-negative bacteria (ceftazidime, cefepime). |

| Invasive GAS (e.g., postvaricella) | Aminoglycoside, carbapenem, or extendedspectrum penicillin with β-lactamase inhibitor Penicillin and clindamycin |

GAS = group A streptococci, GAB = group B streptococci.

FEVER AND RASH

85 What is the differential diagnosis of fever and petechiae?

| Treatable | Nontreatable |

|---|---|

| N. meningitidis (meningococcemia) | Adenovirus |

| N. gonorrhoeae (gonococcemia) | Rubeola (atypical measles) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Enterovirus |

| Streptococcus pyogenes | Epstein-Barr virus |

| Rickettsia prowazekii (epidemic typhus) | |

| Rickettsia rickettsii (Rocky Mountain spotted fever) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus (endocarditis) |

87 What factors predict poor prognosis in infants and children with meningococcemia?

89 List clinical criteria that define toxic shock syndrome.

Minor Criteria

Mucous membrane inflammation (conjunctival or pharyngeal)

Mucous membrane inflammation (conjunctival or pharyngeal)

Gastrointestinal (vomiting, diarrhea)

Gastrointestinal (vomiting, diarrhea)

Musculoskeletal (myalgia or elevation of creatine phosphokinase)

Musculoskeletal (myalgia or elevation of creatine phosphokinase)

Central nervous (alteration of consciousness)

Central nervous (alteration of consciousness)

Hepatic (elevated bilirubin, aminotransferase levels)

Hepatic (elevated bilirubin, aminotransferase levels)

Renal (elevated blood urea nitrogen level, > 5 WBCs/high-power field on urinalysis)

Renal (elevated blood urea nitrogen level, > 5 WBCs/high-power field on urinalysis)

90 Distinguish between staphylococcal and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

TABLE 38-13 STAPHYLOCOCCAL VS. STREPTOCOCCAL TOXIC SHOCK SYNDROME

| Feature | Staphylococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome | Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| General presentation | Acute onset of severe symptoms (vomiting/diarrhea) | Gradual onset of mild symptoms (malaise/myalgia) |

| Fever | High; abrupt onset | Gradual onset (if fever present) |

| Rash | Erythroderma | Scarlatina |

| Shock | Responds to aggressive intravascular volume expansion | Unpredictable response to intra- vascular volume expansion |

| Source of infection | Menstrual related, sinusitis, surgical wound | Cellulitis, necrotizing myositis, fasciitis, pneumonitis |

| Response to antibiotics | Beneficial for treatment of acute infection and recurrence; β- lactamase–resistant penicillins or cephalosporins | More difficult in treating acute infection; clindamycin more superior than β-lactam agents |

| Complications | Infrequent coagulopathies, complicated hospitalizations, gangrene | Common coagulopathies, complicated hospitalization, gangrene |

| Mortality rate | 10% | 30–50% |

91 Which two infectious agents are most commonly associated with erythema multiforme minor and major (Stevens-Johnson syndrome), respectively?

93 What are the typical cutaneous findings associated with scarlet fever?

Erythematous oral mucous membranes with scattered palatal petechiae

Erythematous oral mucous membranes with scattered palatal petechiae

White or red strawberry tongue

White or red strawberry tongue

Erythematous, punctate rash with sandpaper-like texture; first appears on upper trunk, and then becomes more generalized over 3–4 days (more intense in skin folds of axillae, antecubital, popliteal, and inguinal regions, and sites of pressure such as buttocks and small of back)

Erythematous, punctate rash with sandpaper-like texture; first appears on upper trunk, and then becomes more generalized over 3–4 days (more intense in skin folds of axillae, antecubital, popliteal, and inguinal regions, and sites of pressure such as buttocks and small of back)

Pastia’s lines (transverse areas of hyperpigmentation with petechial character in antecubital fossa, axilla, and inguinal regions)

Pastia’s lines (transverse areas of hyperpigmentation with petechial character in antecubital fossa, axilla, and inguinal regions)

Scaly exfoliation on the hands, palms, knees, feet, and perineum within 4–5 days of beginning of sandpaper rash

Scaly exfoliation on the hands, palms, knees, feet, and perineum within 4–5 days of beginning of sandpaper rash

94 Match the following ED scenarios with the appropriate management.

Management Options

| A. A 10-month-old, ill-appearing infant has a history of multiple episodes of vomiting, lethargy, and rapidly spreading rash consistent with petechiae and purpura. The infant is resuscitated immediately (oxygen applied by face mask; IV access obtained; blood, urine, and lumbar puncture performed and laboratory tests ordered; antibiotics given). What antibiotic prophylaxis is needed for the ED staff? | 1. The scenario is most consistent with tuberculosis. Airborne precautions should be taken, which include a private room with negative air-pressure ventilation and properly fitted or sealing respiratory masks to be worn by all health care providers in contact with the patient. |

| B. An 18-year-old man is escorted to the ED from prison with a chief complaint of “coughing up blood.” He has had a chronic cough for approximately 6 months and has lost 10 pounds over the last year. What should the ED staff do to protect themselves from possibly being exposed to this disease? | 2. The scenario is most consistent with meningococcemia. Droplet precautions should be taken, which include the use of a respiratory mask if within 3 feet of the child. Chemoprophylaxis is strongly recommended if mouth-to-mouth resuscitation is provided or there is unprotected contact during endotracheal intubation. Options for chemoprophylaxis include oral rifampin for 2–4 days, intramuscular ceftriaxone for one dose, or oral ciprofloxacin for one dose (the latter is not recommended for use in children < 18 years old). |

| C. A 16-year-old boy with a medical history of mental retardation and cerebral palsy who lives in a long-term care facility has extensive infected decubitus ulcers on his buttocks and lower extremities. What should the ED staff do to protect themselves from being exposed to this disease? | 3. The scenario is most consistent with possible MRSA. Contact precautions should be used, including a private room, gloves at all times, hand washing with an antimicrobial agent after glove removal, and gown use at all times. |

CNS INFECTIONS

96 What are the most common etiologic agents of bacterial meningitis?

0 to 4 weeks: Group B streptococci, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella spp., other gram-negative bacilli, Listeria monocytogenes, enterococci

0 to 4 weeks: Group B streptococci, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella spp., other gram-negative bacilli, Listeria monocytogenes, enterococci

4 weeks to 3 months: Group B streptococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, N. meningitides, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes

4 weeks to 3 months: Group B streptococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, N. meningitides, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes

3 months to 18 years: Streptococcus pneumoniae, N. meningitides, Haemophilus influenzae

3 months to 18 years: Streptococcus pneumoniae, N. meningitides, Haemophilus influenzae

Wubbel L, McCracken GH: Management of bacterial meningitis: 1998. Pediatr Rev 19:78–84, 1998.

97 You are evaluating a 12-month-old infant for possible meningitis. He comes from a community that does not believe in immunization for religious reasons. Given the history, of the three possible pathogens, which should you be most concerned about?

Wubbel L, McCracken GH: Management of bacterial meningitis: 1998. Pediatr Rev 19:78–84, 1998.

100 What empirical antibiotic therapy should be initiated for the treatment of bacterial meningitis outside the neonatal period (> 3 mo)?

101 Should corticosteroids be administered as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of bacterial meningitis?

103 How can viral meningitis be distinguished from bacterial meningitis?

It is often difficult to distinguish these two clinical entities. Both can present with fever, headache, stiff neck, vomiting, and photophobia. Young infants may show nonspecific signs such as irritability, poor oral intake, and somnolence. The typical CSF findings can sometimes be used to distinguish viral from bacterial meningitis, although considerable overlap can exist (Table 38-14).

TABLE 38-14 TYPICAL CEREBROSPINAL FLUID FINDINGS IN VIRAL AND BACTERIAL MENINGITIS

| CSF Variable | Bacterial | Viral |

|---|---|---|

| WBC count (cells/mm3) | >1000 | < 500 |

| Neutrophils (%) | >50 | <50 |

| Glucose level (mg/dL) | <20 | >30 |

| Protein level (mg/dL) | >100 | 50–100 |

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid, WBC = white blood cell.

104 On a hot summer day, a 5-year-old boy presents with fever, headache, and photophobia. You suspect meningitis and perform a lumbar puncture. The CSF evaluation reveals a WBC count of 400 cells/mL with a polymorphonuclear cell predominance, normal glucose, normal protein, and negative Gram stain. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Zaoutis TE, Klein JD: Enterovirus infections. Pediatr Rev 19:183–191, 1998.

105 A 2-week-old infant presents with fever and focal seizures. What therapy should be instituted immediately?

Kohl S: Herpes simplex infections in newborn infants. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 10:154–160, 1999.

106 A 10-year-old boy has a fever and is suddenly acting strangely, with combative behavior and garbled speech. What is the differential diagnosis for this presentation?

Russell CD: Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 14:90–95, 2003.

107 A 12-year-old boy with a 2-week history of sinusitis presents with persistent fever, headache, and altered mental status. What serious complication of sinusitis should be considered?

Wald ER: Clinical features, evaluation and diagnosis of acute bacterial sinusitis in children, 2006: www.uptodate.com

108 An 8-year-old boy has fever and back pain. What is your approach to diagnosis and management?

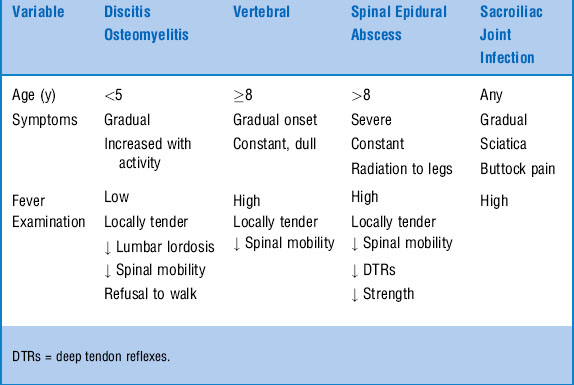

Back pain is an unusual reason for children to be seen in the ED. Frequently, back pain in children indicates significant disease. The differential diagnosis includes infectious, neoplastic, and rheumatologic disorders. The major infections producing back pain in children include discitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, spinal epidural abscess, and sacroiliac joint infection (Table 38-15).

TICK-BORNE DISEASE

110 What is the recommended treatment for Lyme disease in children?

| Disease Stage | Clinical Manifestations | Drug |

|---|---|---|

| Early localized | Erythema migrans, malaise, myalgia | Doxycycline (amoxicillin*), 14–21 days |

| Early disseminated | Multiple erythema migrans rashes | Doxycycline (amoxicillin), 21 days |

| Facial palsy | Doxycycline (amoxicillin), 21–28 days | |

| Arthritis | Doxycycline (amoxicillin), 28 days | |

| Late disseminated | Persistent arthritis, carditis | IV ceftriaxone, 14–21 days |

| Meningitis or encephalitis | IV ceftriaxone, 30–60 days |

Penicillin-allergic patients can be treated with cefuroxime axetil and erythromycin.

* ≥8 years old, treat with doxycycline; <8 years old, treat with amoxicillin.

Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics: Lyme disease. In: Pickering LK (ed): Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006, pp 428–432.

112 A 16-year-old otherwise healthy girl presents with a syncopal episode. electrocardiography reveals complete heart block. What is the differential diagnosis?

113 What is the time course of clinical manifestations of Lyme disease?

TABLE 38-17 TIME COURSE OF CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF LYME DISEASE

| Stage | Clinical Manifestations | Time after Exposure |

|---|---|---|

| Early localized | Single EM lesion, myalgia, headache, arthralgia, fever, fatigue | 3–32 days |

| Early disseminated | Single or multiple EM lesions, arthralgia, neck pain and/or stiffness, cranial neuritis (facial nerve palsy), meningitis, radiculoneuritis | 3–10 weeks |

| Late disseminated | Arthritis, carditis, encephalomyelitis | 2–12 months |

EM = erythema migrans.

114 Describe the distribution of the rash in RMSF.

GASTROINTESTINAL INFECTIONS

118 When a child is found to have bloody diarrhea, which infectious agents are most likely responsible?

119 Which bacterial stool pathogens require antimicrobial treatment?

Shigella: Most infections are self-limiting; however, antibiotics can reduce the length of symptoms. Antibiotics are therefore recommended for severe disease with dehydration, or in immunocompromised individuals.

Shigella: Most infections are self-limiting; however, antibiotics can reduce the length of symptoms. Antibiotics are therefore recommended for severe disease with dehydration, or in immunocompromised individuals.

Salmonella: Treatment does not shorten the duration of the symptoms and may actually prolong the carrier state. However, bacteremia is common in infants younger than 3 months of age, in patients with sickle cell disease, and in other immunocompromised individuals. Therefore, treatment should be considered if bacteremia is suspected in this population.

Salmonella: Treatment does not shorten the duration of the symptoms and may actually prolong the carrier state. However, bacteremia is common in infants younger than 3 months of age, in patients with sickle cell disease, and in other immunocompromised individuals. Therefore, treatment should be considered if bacteremia is suspected in this population.

E. coli O157:H7: No treatment because there is no proven benefit. A meta-analysis failed to confirm an increased risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome in patients treated with antibiotics.

E. coli O157:H7: No treatment because there is no proven benefit. A meta-analysis failed to confirm an increased risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome in patients treated with antibiotics.

120 A 2-year-old presents with vomiting, profuse diarrhea, and new-onset seizures. What could be responsible for this clinical picture?

122 Which organisms cause food-borne illnesses? How can you distinguish them?

TABLE 38-18 ONSET, SYMPTOMS, AND ETIOLOGY OF FOOD-BORNE ILLNESS

| Time of Onset | Main Symptoms | Organism or Toxin |

|---|---|---|

| Upper GI Tract | ||

| 1–6 hours | Nausea, vomiting, usually afebrile | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 1–6 hours | Nausea, vomiting, afebrile | Bacillus cereus (emetic form) |

| Lower GI Tract | ||

| 8–16 hours | Diarrhea, afebrile | Bacillus cereus (diarrheal form) |

| 6–24 hours | Foul-smelling diarrhea, cramps, afebrile | Clostridium perfringens |

| 16–48 hours | Abdominal cramps, diarrhea, fever | Vibrio cholerae, Norwalk virus, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Cryptosporidium spp. |

| 16–72 hours | Bloody diarrhea, fever, abdominal cramps | Salmonella, Shigella, and Campylobacter spp., E. coli |

| 16–72 hours | Bloody diarrhea, fever, pseudoappendicitis, pharyngitis | Yersinia enterocolitica |

| 1–6 weeks | Mucoid diarrhea (fatty stools), abdominal pain, weight loss | Giardia lamblia |

| Neurologic Infection | ||

| 12–36 hours | Vertigo, diplopia, areflexia, weakness, difficulty breathing and swallowing, constipation | Clostridium botulinum |

| Generalized Infection | ||

| 14 days | All of the above symptoms, plus vomiting, rose spots, constipation, abdominal pain, fever, chills, malaise, swollen lymph nodes | Salmonella typhi |

Adapted from American Academy of Pediatrics: Appendix VI: Clinical syndromes associated with food borne diseases. In Pickering LK (ed): Red Book: 2006 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2006, pp 858-860.

123 A 3-month-old infant presents with a 3-day history of constipation, progressively poor feeding, and lethargy. On physical examination you notice a quiet, inactive child who is otherwise alert with good perfusion. The neurologic examination reveals a weak cry, poor suck, and hypotonia. What is the likely diagnosis?

125 A 5-year-old who resides in a group home is transported to the ED because he looks “yellow.” What are the diagnostic considerations?

1 Send stool cultures for Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, and Campylobacter spp., and E. coli testing.

2 Initiate antimicrobial treatment for Salmonella and Shigella infections if the patient is clinically unstable, severely dehydrated, immunocompromised, or < 3 months of age.

3 Consider other noninfectious causes (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease).

BITES

126 Which animals should be considered at high risk for transmission of rabies? How is rabies managed?

127 Should a child who has been in proximity to bats (e.g., in the same room during sleep), but without known physical contact, receive prophylaxis?

RESPIRATORY ILLNESSES

130 An afebrile 2-month-old presents with tachypnea and cough. What are the causes of pneumonia in this age group?

131 Describe the acute management of bronchiolitis due to respiratory syncytial virus.

Supportive treatment (mist treatments, suction, oxygen if needed)

Supportive treatment (mist treatments, suction, oxygen if needed)

Ensure hydration (IV fluid if dehydrated)

Ensure hydration (IV fluid if dehydrated)

Chest radiographs to determine severity

Chest radiographs to determine severity

Trial of bronchodilator (albuterol nebulized treatment), although various studies have demonstrated variable response

Trial of bronchodilator (albuterol nebulized treatment), although various studies have demonstrated variable response

Racemic epinephrine for moderate to severe cases of bronchiolitis (has been shown to decrease respiratory distress [i.e., respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and clinical scores])

Racemic epinephrine for moderate to severe cases of bronchiolitis (has been shown to decrease respiratory distress [i.e., respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and clinical scores])

Dexamethasone is not indicated in respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis, although several studies using nebulized budesonide demonstrate variable results

Dexamethasone is not indicated in respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis, although several studies using nebulized budesonide demonstrate variable results

132 What is the treatment of choice for presumed C. trachomatis infection (either conjunctivitis or pneumonia)?

135 What are the most common types of pneumonia in a 2-year-old?

Respiratory viruses are the most common causes of pneumonia in toddlers. Causes include:

Hendricskon KJ: Viral pneumonia in children. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis 3:217–233, 1998.

137 What clinical clues suggest typical bacterial pneumonia?

Lichenstein R, Suggs A, Campbell J: Pediatric pneumonia. Emerg Med Clin North Am 21:437–451, 2003.

139 A 10-year-old presents with nonproductive cough, low-grade fever, and malaise. On physical examination, the patient appears well, has minimal respiratory distress, and has bilateral lower lung field crackles. What is the most frequent cause of pneumonia in this age group?

Katz B, Waites K: Emerging intracellular bacterial infections. Clin Lab Med 24:627–649, 2004.

KEY POINTS: COMMON ETIOLOGIC AGENTS OF PNEUMONIA IN CHILDREN

1 Neonate: Group B streptococci, E. coli, and other gram-negative bacilli, Listeria monocytogenes, Ureaplasma urealyticum (premature)

2 Infant(< 3 months): Respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, parainfluenza, adenovirus, Chlamydia trachomatis

3 Infant to toddler (< 5 years): Respiratory viruses, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae

4 School age to adolescence: M. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae, S. pneumoniae, respiratory viruses

ORTHOPEDIC INFECTIONS

143 A 2-year-old presents with a limp. A radiograph of the suspected limb is negative. Does a negative radiograph eliminate the possibility of osteomyelitis?

144 What is the classically described position that the leg is held in by a child with septic arthritis of the hip?

146 Aspiration of the hip joint in a 2-year-old febrile child with a limp reveals a WBC count of 60,000 cells/mm3 with a neutrophil predominance. What diagnosis is likely?

Septic arthritis is most likely. However, Table 38-19 can aid in diagnosis based on the WBC count and differential but demonstrates considerable overlap. Epidemiology, presence of fever, and detailed history may help.

TABLE 38-19 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF SEPTIC ARTHRITIS BASED ON WHITE BLOOD CELL COUNT AND NEUTROPHILS

| Diagnosis | White Blood Cells (cells/mm3) | Neutrophils (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Normal | <200 | 10–20 |

| Traumatic effusion | <2000 | 10–30 |

| Rheumatologic | 10,000–50,000 | 50–80 |

| Septic arthritis | >50,000 | ≥80 |

| Lyme disease | 15–125,000 | >50 |

147 Match the disease with the appropriate management plan.

| 1. Osteomyelitis 2. Septic arthritis of hip 3. Toxic synovitis | A. No antibiotics needed. Anti-inflammatory medications may be needed. |

| B. Admission to hospital. No IV antibiotics until patient is evaluated by orthopedic surgery and cultures of bone have been obtained. | |

| C. Emergency, requiring surgical drainage and IV antibiotics. |

148 What are the most common organisms found in bone and joint infections?

TABLE 38-20 Organisms Most Commonly Found in Bone and Joint Infections*

| Age | Septic Arthritis | Osteomyelitis |

|---|---|---|

| Neonate | Staphylococcus aureus | S. aureus |

| Group B streptococci | Group B streptococci | |

| Gram-negative bacilli | Gram-negative bacilli | |

| Toddler | S. aureus | S. aureus |

| Group A streptococci | Group A streptococci | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Kingella kingae | |

| Kingella kingae | ||

| School-age | S. aureus | S. aureus |

| Group A streptococci | Group A streptococci |

* In sexually active adolescents, also consider Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Salmonella sp. is a common cause of osteomyelitis in children with sickle cell disease.

Adapted from Frank G, Mahoney HM, Eppes SC: Musculoskeletal infections in children. Pediatr Clin North Am 52:1083–1106, 2005; and Gutierrez K: Bone and joint infections in children. Pediatr Clin North Am 52:779–794, 2005.

VIRAL ILLNESSES/EXANTHEMS

151 A medical student reports to you that a 3-year-old, febrile child appears to have been slapped on both cheeks by someone. What infectious disease are you considering?

152 A 15-year-old with fever, exudative pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly presents to the ED. You suspect infectious mononucleosis. What laboratory tests should be obtained to aid in diagnosis?

153 What should you recommend to a patient with infectious mononucleosis upon discharge from the ED?

155 Match the disease with the clinical description.

| 1. Varicella (chicken pox) | A. Fever, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis. Confluent maculopapular rash beginning on upper part of body; can involve palms and soles. |

| 2. Measles 3. Rubella |

B. Fever; coalescent, pink, maculopapular rash that begins on face and extends downwards; tender postauricular, suboccipital, and posterior cervical lymph nodes. Prodromal symptoms of cough, malaise, and conjunctivitis are uncommon. |

| C. Prodrome of fever, papules, vesicles, and umbilicated and scabbed lesions. Hallmark is lesions present in different stages at the same time. Lesions develop in crops. Initial lesion typically in scalp and lesions can involve oral mucosa. |

157 A child with varicella presents with chicken pox, high fever, and toxic appearance. What should you suspect?

158 A 1-year-old infant has fever and rash 10 days after the annual visit to the pediatrician. What important history should be obtained regarding the recent visit to the pediatrician?

KAWASAKI DISEASE

161 What is the differential diagnosis of Kawasaki disease?

Dedeoglu F, Sundei RP: Vasculitis in children. Pediatr Clin North Am 52:547–575, 2005.

162 What laboratory findings support the diagnosis of Kawasaki disease?

BIOTERRORISM INFECTIONS

164 What are some agents of bioterrorism?

Category A agents: Anthrax, smallpox, plague, tularemia, hemorrhagic fever viruses, botulinum toxin

Category A agents: Anthrax, smallpox, plague, tularemia, hemorrhagic fever viruses, botulinum toxin

Category B agents: Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), Brucella species, Burkholderia mallei, alphaviruses (Venezuelan, eastern, and western equine encephalomyelitis), Salmonella species, Shigella dysenteriae, E. coli O157:H7, Vibrio cholerae, Cryptosporidium parvum

Category B agents: Coxiella burnetii (Q fever), Brucella species, Burkholderia mallei, alphaviruses (Venezuelan, eastern, and western equine encephalomyelitis), Salmonella species, Shigella dysenteriae, E. coli O157:H7, Vibrio cholerae, Cryptosporidium parvum

Category C agents: Hantavirus, tick-borne hemorrhagic fever viruses, yellow fever, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (multidrug-resistant).

Category C agents: Hantavirus, tick-borne hemorrhagic fever viruses, yellow fever, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis (multidrug-resistant).

Shannon M: Management of infectious agents of bioterrorism. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 5:63–71, 2004.

165 Match the bioterrorist disease with the organism and symptoms.

| A. Anthrax B. Tularemia C. Plague D. Smallpox |

1. Gram-negative rod resulting in pneumonia-like illness with fever, cough, dyspnea, large lymph node (bubo), and hemoptysis 2–4 days after exposure. Chest radiograph reveals bilateral infiltrates or lobar consolidation. |

| 2. Spore forming gram-positive bacillus resulting in a flulike illness: fever, chills, malaise, nonproductive cough, absence of rhinorrhea. Chest radiograph reveals widened mediastinum. | |

| 3. Gram-negative coccobacillus resulting in possible skin ulceration, pharyngitis, conjunctival injection, lymphadenitis, fever, pneumonia. Chest radiograph reveals hilar adenopathy. | |

| 4. Member of the Poxviridae family and resulting in low-grade fever, vesicular centrifugal rash 14 days after exposure. Lesions are umbilicated and in the same stage of development. |

Answers: A, 2; B, 3; C,1; D, 4.

Shannon M: Management of infectious agents of bioterrorism. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med 5:63–71, 2004.

METHICILLIN-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS INFECTIONS

167 What antimicrobials would you use to treat community-acquired MRSA?

Lowy FD, Kaplan SL: Treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children, 2006: www.uptodate.com

UNUSUAL INFECTIONS

1 Fleisher GR. Infectious disease emergencies. In: Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM, editors. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine. 5th ed. Baltimore, Lipppincott: Willliams & Wilkins; 2006:783-853.

2 Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 2nd ed., New York: Churchill Livingstone, 2003.