16 Infectious disease and immunity

Introduction

Immunization protects children from a range of deadly infections (see Chapter 1, p. 3 for UK immunization schedule), but a 4-year-old can still expect 6 to 10 illnesses per year – usually viral. Thus, infectious disease is ubiquitous in children. In many countries, diseases such as measles and gastroenteritis remain major causes of death, especially when combined with malnutrition.

Examination

Non-blanching rashes are highly concerning. Petechiae are less than 1 mm in diameter and may signify bacterial infection but are common in viral illnesses where observation for a minimum of 4 hours is recommended. When present in the distribution of the area drained by the superior vena cava, look for causes of raised intrathoracic pressure – principally prolonged coughing or vomiting. Purpura (spots greater than 1 mm) in a child who is unwell and who has a temperature should be taken as evidence of meningococcal septicaemia and treated as an emergency (see Appendix I, p. 288).

Investigations

A urine sample is always important but not always easy to collect (see Chapter 11, p. 118). Take swabs from vesicles, purulent lesions and weeping skin. There are different swabs and transport media for bacteria, viruses and Chlamydia – make sure that the right one is used.

A throat swab is sometimes useful in sore throats but always important in meningitis where growth correlates with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings. Lumbar puncture is the gold standard test for diagnosing meningitis and should be considered whenever meningitis remains a possible diagnosis. There is a small but significant risk of coning (see Chapter 14, p. 188) if lumbar puncture is performed in acutely ill infants. In these circumstances, delayed lumbar puncture is safer (see Box 16.1).

Box 16.1

Contraindications to lumbar puncture

For lumbar puncture results and interpretation see meningitis, below.

Possible meningitis

Unconscious or drowsy children should be assumed to have meningitis or encephalitis. Irritability implies cerebral irritation and may be hard to distinguish from children who are simply feverish, frightened and miserable. A smile, some desultory play or even well-organized objection to examination is reassuring. Children with a high-pitched cry or who cannot be comforted are of concern. Seizures with a fever are usually febrile seizures in children aged 6 months to 5 years (see Chapter 14, p. 190) but meningitis, encephalitis and brain abscess may also cause seizures – especially in infants.

Investigation

In Case 16.1, the clinical diagnosis is meningitis. The likely causes are listed in Table 16.1. Early treatment may be life-saving, and antibiotics should be given as soon as possible. Intramuscular or intravenous penicillin can be given by GPs or paramedics. In hospital, intravenous cannulation will allow blood for blood culture, blood count and clotting studies to be drawn before the first antibiotic dose is given. Lumbar puncture – provided there is no contraindication – can be performed once treatment is underway. Do not wait to give antibiotics in a child who is obviously unwell.

| Age | Pathogens | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Neonatal period (birth-28 days) | Streptococcus group B Escherichia coli Other coliforms Listeria monocytogenes |

Amoxicillin and gentamicin or cefotaxime |

| 28 days and older | Meningococcus Haemophilus influenzae Pneumococcus |

Ceftriaxone |

| Any age | Viruses: enterovirus, mumps, influenza | Supportive |

| Any age | Tuberculosis | Seek specialist advice |

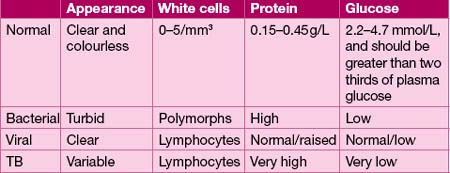

Lumbar puncture will confirm the diagnosis of meningitis and help determine the cause (Table 16.2). Even if antibiotics prevent growth from CSF culture, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) will detect bacterial DNA in blood or CSF and enable a diagnosis.

Bacterial meningitis still has a mortality of around 5%; meningococcal septicaemia is even more dangerous, with reported mortality very high if the initial presentation is with shock. Of the survivors, 10% have sequelae – most commonly deafness, especially after pneumococcal meningitis. Hearing screening should be performed on all children after meningitis (see also Chapter 14, p. 206).

Encephalitis

Diagnosis of encephalitis is a clinical dilemma, as shown in Case 16.2. Why is the boy so drowsy? He could have post-ictal drowsiness following febrile seizures, but the history suggests encephalitis. Lumbar puncture will normally show a CSF lymphocytosis suggesting brain inflammation secondary to encephalitis, tuberculous meningitis, or partially treated bacterial meningitis where there is a history of antibiotic use. Send CSF and stool for virology and seek specialist microbiological advice. Diarrhoea may indicate an enterovirus infection. Most viral encephalitis is self-limiting, but herpes simplex encephalitis is often aggressive and damaging. Children with encephalitis are therefore treated with aciclovir until the diagnosis is clear. Children may also get encephalitis after viral infections as part of the immune response to the original infection. Measles, mumps, varicella and rubella can all do this.

Fever and a rash

This is a common presentation. It may help to sort these cases out using the following scheme:

1. Could the child be seriously ill? Many viral infections produce a non-specific rash and fever. It is often not possible to make an accurate diagnosis, in which case the trick is to sort out those who are worryingly ill from those who are not.

2. Has the child been given antibiotics? You could be observing a sensitivity reaction or a modified presentation of a bacterial infection.

Non-blanching rash

If the rash does not blanch on pressure, it could be meningococcal infection. A purpuric rash may also occur with Henoch–Schönlein purpura (see Chapter 6, p. 55), but the child does not appear markedly unwell, and the distribution of the rash over the buttocks, extensor forearms and lower limbs is characteristic (so-called ‘gravitational’ distribution of rash).

Meningococcal septicaemia

The cause of meningococcal infection – Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus) – may present with meningitis, or, as is the case in Case 16.3, an overwhelming septicaemic illness. This occurs at any age and may progress with frightening speed.

Antibiotic therapy is imperative, and shock and multiorgan failure are likely with such a presentation (for management, see Appendix I, p. 288). High dependency or intensive care is imperative. Lumbar puncture to confirm meningitis is deferred until the child is stable. The initial rash in meningococcal septicaemia may be a blanching, maculopapular rash, but it quickly changes character to become petechial or purpuric.

Generalized maculopapular rash

Rubella

Rubella is a relatively trivial illness. The rash typically lasts about 3 days, and comprises fine 1–4 mm pink maculopapules (as in Case 16.5). Particularly in adolescents, it may be preceded by an upper respiratory tract prodrome – painful eye movements are characteristic. A troublesome post-viral arthropathy may follow. Rubella is important because it causes significant damage to the fetus if acquired by a pregnant mother. Rubella embryopathy comprises the triad of deafness, cataracts and retinopathy, and congenital heart disease, coupled with other features. It is entirely preventable. Women found not to be rubella-immune in pregnancy are offered immunization after pregnancy.

Roseola infantum

Roseola infantum is a harmless infection caused by human herpes virus 6B (HHV6B). Febrile seizures occur with it quite commonly, as in Case 16.6. The characteristic feature is the appearance of the rash, concurrent with remission of fever. The rash is a diffuse maculopapular, rose-pink rash, readily distinguished from measles by the remission of fever. Neutropenia, as in Case 16.6, is characteristically found.

Slapped-cheek disease

Case 16.7 gives an example of a condition that is caused by parvovirus B19. Children with sickle-cell anaemia or other haemolytic anaemias may develop a severe aplastic crisis (see Chapter 7, p. 61). The fetus may develop hydrops fetalis if a mother catches this infection while pregnant.

Urticaria

Some of the most dramatic rashes you will ever see are urticarial. Large red wheals usually with an irregular, raised edge are found on the trunk. The rash may come and go within a few hours, sometimes leaving a slightly bruised appearance. Symptomatic treatment with antihistamines and prednisolone is effective. (see Chapter 8, p. 83).

Generalized vesicular rash

Chicken pox

Case 16.8 is an example of chicken pox (varicella) which is caused by varicella zoster, a herpes group virus. In most children the systemic upset and the rash are mild but a few children are covered with spots and are thoroughly miserable. Following exposure, viraemia develops about 6 days after infection, with fever. Subsequently, fever, malaise and abdominal pain develop, before the onset of the rash about 10–14 days after initial contact (though it may be as late as 21 days).

Rash restricted to one site

Impetigo, erysipelas and cellulitis are cutaneous infections caused by staphylococci or streptococci (see Chapter 8, p. 84). Impetigo and erysipelas usually affect the face. There are obvious local inflammatory changes, sometimes with regional lymphadenopathy. Cellulitis may overlie osteomyelitis (see Chapter 6, p. 51). Treatment is with oral or intravenous antibiotics. Red, painful raised lesions over the shins, erythema nodosum, may occur with drug reactions and a variety of infections or inflammatory disorders (see Chapter 8, p. 84).

Sore throat

Glandular fever

Case 16.9 is an example of glandular fever, a condition that has an ominous reputation among adolescents for causing prolonged illness. This reputation is offset to some extent by the kudos of catching a disease thought to be spread by kissing! The incubation period is about 6 weeks. Glandular fever can be very unpleasant in the acute stage but most children make a prompt recovery. Typical symptoms include sore throat, flu-like symptoms, malaise, swelling around the eyes (20%) and a diffuse maculopapular rash (10%). Subclinical hepatitis is usual, with derangement of liver function tests, but overt jaundice is uncommon. The causative agent – Epstein–Barr virus – may be detected on paired antibody titres. Cytomegalovirus and toxoplasmosis may cause a similar illness. A glandular fever-like illness accompanies seroconversion in some HIV-infected patients. The monospot and Paul Bunnell screening tests are useful for Epstein–Barr virus, but false positives and false negatives occur. Ampicillin or amoxicillin must be avoided in the empirical treatment of sore throat – as a florid maculopapular rash occurs, typically 10–14 days later – and may be complicated by Stevens–Johnson syndrome (Chapter 8, p. 84). Treatment is usually supportive. Steroids may be used to reduce airway obstruction or swallowing difficulty secondary to severe tonsillar enlargement.

Scarlet fever

The girl in Case 16.10 has scarlet fever. The primary cause is usually a toxin-producing beta-haemolytic group A Streptococcus, although staphylococcal scarlet fever may also occur. The toxin produces generalized erythema. Treatment is with a 10-day course of penicillin or a macrolide antibiotic such as azithromycin. Late complications include pneumonia, rheumatic fever (see Chapter 6, p. 57) and acute nephritis (see Chapter 11, p. 129). Kawasaki’s disease may present similarly (see below).

Kawasaki’s disease

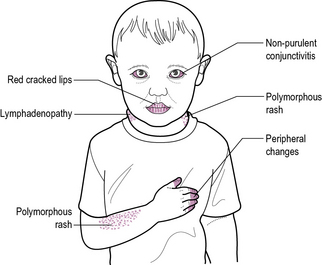

Kawasaki’s disease is a vasculitic disorder of unknown aetiology. The key feature is an unremitting high fever lasting for 5 days or more in a child who is irritable and unwell. It is rare but is serious and treatable. The principal differential diagnosis is scarlet fever (see above) (see Figure 16.1).

About 5% of children, especially young boys, develop coronary artery aneurysms. Follow-up echocardiography is necessary to monitor for this complication. Sudden cardiac death (see also Chapter 9, p. 98) is a rare complication of coronary artery aneurysms, or other cardiac complications.

Fever and rash associated with mouth ulcers and lesions on the lips

Herpes simplex

Herpes simplex virus may cause cold sores in older children and adults. These are acutely painful red swollen lesions of the lips with a pus-filled centre. Younger children who acquire herpes for the first time may get herpetic gingivostomatitis. This produces an acutely painful ulcerated mouth, tongue and lips. Children may be unable to swallow and need intravenous fluids. Oral aciclovir treatment speeds recovery. Mouth ulcers also occur with enteroviral infections, particularly coxsackie virus (see also Chapter 8, p. 85).

Fever and rash affecting the palms or soles

The commonest infectious cause is hand, foot and mouth disease, caused by coxsackie viruses, which also produces vesicles on the skin and mouth ulcers. Erythema multiforme with its characteristic target lesions may also affect the hands and feet. Mucosal involvement may signify Stevens–Johnson syndrome (see Chapter 8, p. 84).

Fever and specific symptoms

Specific symptoms accompany many infections:

• Dyspnoea and respiratory distress in pneumonia and bronchiolitis

• Intractable cough in pertussis

• Diarrhoea and vomiting in gastroenteritis

• Loin pain or dysuria in urinary tract infection

Immune deficiency

See Box 16.2 for investigation of suspected immunodeficiency.

Antibody deficiency may be treated with regular infusions of immunoglobulin.

Defective cell-mediated immunity is seen with Di George syndrome (see Chapter 18, p. 272) due to thymic hypoplasia, but normally a degree of recovery takes place. Thymus transplantation may be performed if necessary. More severe disorders of cell-mediated immunity include severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and HIV/AIDS.

See Box 16.3 for the management of immune deficiency.

Human immunodeficiency virus

Treatment

• Anti-retroviral therapy. There are two classes of reverse transcriptase inhibitors, dideoxynucleosides and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, which act to inhibit viral reverse transcriptase, thus suppressing HIV replication. Protease inhibitors inhibit formation of vital structural proteins. Combination anti-retroviral therapy (ART), with three drugs, delays progression of the disease. In the initial phase, highly active ART (HAART) is used to quickly reduce the viral load and prevent emergence of resistance, but treatment regimes are difficult and complex, and non-compliance with therapy is common.

• Immunizations. HIV-infected children receive the normal immunization schedule. As for all patients at increased risk of chest infection, pneumococcal and influenza vaccines are recommended.

• Infection prophylaxis. Routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended because of problems with resistant organisms. Monthly immunoglobulin therapy may be given, but is of uncertain value. Prophylaxis with co-trimoxazole is used in infants to prevent Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) until 1 year of age, or after PCP infection, or in children with low CD4 counts. Clarithromycin is used to prevent Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex (MAC) infection in children with very low CD4 counts. Children exposed to virus infections, such as measles, chicken pox or herpes, receive immunoglobulin and, if appropriate, aciclovir.

Complications

• Serious bacterial sepsis. There is a high risk of serious sepsis in HIV-infected children, including septicaemia (10% per year), particularly with Pneumococcus.

• PCP. This is common in infancy, when it is often the first presentation. PCP is often fatal (30–50%) and has a poor prognosis, with post-infection 2-year survival less than 50%.

• Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy. The peak incidence is between 9 and 18 months of age with progressive loss of intellectual and neurological impairment. Gross cerebral atrophy is seen on CT scan.

• Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis. This is common in preschool children, and may be asymptomatic, otherwise it presents with chronic cough and dyspnoea, and reticulonodular shadowing on chest X-ray. Prednisolone is effective.

• Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, particularly of the central nervous system, is the most common HIV-related malignancy in childhood.