133 Infections of the Urogenital Tract

Infections in the intensive care unit (ICU) contribute significantly to patient morbidity. Depending on the type of ICU, nosocomial infections may account for 70% of infections.1 Nosocomial infections of the urogenital tract are frequent and sometimes underestimated in the ICU.2

Definition

Definition

Urinary tract infection can be the primary cause for admission to the ICU or can be acquired after intensive care procedures. Because patients are frequently sedated in the ICU, clinical diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) is often difficult. Nevertheless, UTI is an important cause of morbidity and antibiotic resistance in the ICU. Complicated UTI is a very heterogeneous entity, with a common pattern of the following factors3,4:

Etiology

Etiology

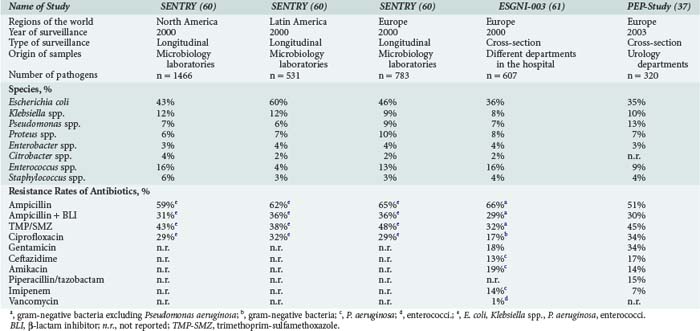

Causative pathogens of UTI are almost exclusively bacteria and yeast. Viral pathogens are only found in patients with severe immunosuppression, such as after bone marrow transplantation. High antibiotic pressure and special circumstances in the ICU modulate the microbial spectrum. Escherichia coli is the most frequent pathogen but occurs less frequently than in uncomplicated community-acquired UTI. Other Enterobacteriaceae may also be uropathogens (e.g., Klebsiella, Proteus, Enterobacter, Serratia, Citrobacter, or Morganella species). Non-fermenters such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, gram-positive cocci such as staphylococci and enterococci, and Candida species may also play an important role (Table 133-1). The microbial spectrum is likely to differ over time and from one institution to the next. To follow the spectrum and development of antibiotic resistance, each ICU has to update its own analyses.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

The Extended Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC II) study1 revealed that 51% of patients were infected on the study day, and 71% of all patients were receiving antibiotics. The total occurrence of the most frequent types of ICU-acquired infection were respiratory tract infections 63.5%, abdominal infections 19.6%, bloodstream infections 15.1%, and renal or urinary tract infections in 14.3%.1 The true incidence of UTI, however, may be even higher if meticulously looked for. In a prospective study specifically evaluating nosocomial UTI, nosocomial UTIs accounted for 28% of the nosocomial infections, lower respiratory tract infections for 21%, pneumonia for 12%, and bloodstream infections for 11%. The rates of urinary catheter–associated UTIs varied between 4.2% (symptomatic UTI) and 14.0% (asymptomatic UTI), which shows that asymptomatic bacteriuria is frequent in ICU patients, although symptoms of UTIs in intensive care patients are frequently difficult to assess.2 In the one-day point prevalence study in urological patients in Europe (PEP/PEAP study) asymptomatic bacteriuria accounted for 29% of nosocomial UTIs, followed by cystitis (26%), pyelonephritis (21%), and urosepsis (12%),5 showing that nosocomial UTI is present with high frequency in certain patient groups.

Urinary tract infections in the ICU are divided into two groups:

Urinary Tract Infections with Nonurologic Complicating Causes

Individuals with diabetes are at higher risk for urinary tract infection.6 Increased susceptibility in patients with diabetes is positively associated with increased duration and severity of diabetes as a result of impaired granulocyte function, decreased excretion of Tamm-Horsfall protein, low interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 levels in the urine that lead to lower “cidality” of the urine, and altered microflora in the genital region. In addition, diabetic cystopathy and nephropathy may be complicating factors in the urinary tract. In addition to antibiotics, treatment must address the metabolic situation. In pyelonephritis, usually a switch to insulin or to insulin-analogous therapy is necessary.

Immunosuppression is generally associated with increased risk of UTI. Patients with leukopenia (<1000/µL) show a higher rate of febrile UTIs and bacteremia due to UTI.4 Symptoms and findings in these patients frequently are not diagnostic. Febrile episodes, however, are due to infections in approximately 60% of cases.

Pathogens may be translocated into the urinary tract from contiguous infectious foci (e.g., appendicitis, sigmoid diverticulitis, translocation by ileus). Symptoms and localization of pain can be misleading and may delay diagnosis. Operations or trauma may cause hypothermia, tissue hypoxia, and hemodynamic alterations that produce kidney dysfunction and impaired mucosal perfusion. The use of latex catheters in these critical situations (e.g., operations with heart-lung machine) can also lead to urethral strictures. Silicone catheters or suprapubic catheters are recommended in these patients.7 Suprapubic catheters cannot prevent UTI. They can, however, lower the rate of UTI from 40% to 18%.8

Urinary Tract Infections with Urologic Complicating Causes

Patients show a high risk to develop bacteriuria after renal transplantation, threatening clinical outcomes for both the patient and transplant. Early infections (up to 3 months after transplantation) are differentiated from late infections (more than 3 months after transplantation). Early infections may present with no symptoms. In this phase, occult bacteremia (60% of bacteremias after renal transplantation originate from the urinary tract), allograft dysfunction, and recurrent UTI after antibiotic therapy are frequently seen.4 The newer immunosuppressive agents are associated with a lower incidence of rejection but a higher risk of late infection. In particular, mycophenolate mofetil is associated with an increasing incidence of UTI and with infections caused by cytomegalovirus.4 Infection can induce graft failure by the direct effect of cytokines and free radicals or reactivation of cytomegalovirus infection. It can be very difficult to distinguish rejection from infection.4 Patients must also be investigated for a surgical complication.

UTIs caused by Candida species are frequently asymptomatic. There is, however, a risk of obstructive fungal balls leading to candidemia or invasion of the anastomosis in renal transplant recipients. Asymptomatic candiduria should therefore be treated in these patients.4 Urine transport disturbances (e.g., from obstructive ureteral stone) require specific urologic therapy such as percutaneous nephrostomy or stenting. In the case of bladder obstruction, an indwelling urinary catheter (suprapubic or transurethral) will be the primary therapy in the ICU. Long-term indwelling catheters (more than 30 days) are associated with a selected microbial spectrum of difficult-to-treat uropathogens (e.g., Providencia spp., Proteus spp., Pseudomonas spp.).9 After initiation of antimicrobial therapy, the catheter should be exchanged to remove biofilm material.

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

In uncomplicated UTI, pathogens need to have very specific virulence factors enabling them to initiate an infection after invasion of the urinary tract. The medical conditions of an ICU patient may weaken physiologic barriers and defenses, thus facilitating entry of pathogens. In addition, the nosocomial environment in the ICU, including antibiotic pressure and decreased supply of oxygen or nutrients (e.g., iron) to tissues, can select pathogens with specific resistance patterns. A general adaptation strategy is the formation of hypermutator strains, which show 100- to 1000-fold increased mutation frequencies, enabling the pathogens to rapidly adapt to challenging environments and to thus develop effective mechanisms for antibiotic resistance.10,11

The basic structural unit of a biofilm is a microcolony—that is, a discrete matrix-enclosed community consisting of bacteria of one or more species. The biofilm is usually built up of three layers12,13:

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Urinary Examinations

Dipstick Test

The dipstick test is done with undiluted urine and investigates the following infection-related parameters15:

Microscopy

There are two possibilities of microscopic evaluation15:

TABLE 133-2 Standard Values for Urine in Counting Chamber and Field of Vision

| Erythrocytes | Leukocytes | |

|---|---|---|

| Uncentrifuged urine (chamber counting) | <10/mL | <10/mL |

Data from European Urinalysis Guidelines, 2000.

Clinical Diagnosis

To survey and compare infection rates in different institutions, UTIs should be classified according to widely accepted definitions, such as the definitions of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The CDC/National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) definitions16 stratify health care associated UTIs into symptomatic, asymptomatic, and other infections of the urinary tract. To be of value in determining a nosocomial infection, the urine specimens must be obtained aseptically using an appropriate technique such as clean catch collection, bladder catheterization, or suprapubic aspiration.

Therapy

Therapy

General Principles

Not all bacteriuric patients in the ICU need to be treated. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in general does not have to be treated.17 Therapy should only be started in patients with significant symptoms and morbidity and in whom asymptomatic bacteriuria may be deleterious (e.g., before traumatizing intervention of the urinary tract and in pregnant women). In the ICU, indications for treatment of asymptomatic UTI might include some other circumstances such as renal transplant, severe diabetes mellitus, or severe immunosuppression. In complicated UTI, antibiotic therapy can only be successful when the complicating factors can be eliminated or urodynamic functions restored. Treatment of complicated UTI therefore comprises adequate antibiotic treatment and successful urologic intervention.

Antibiotic Therapy

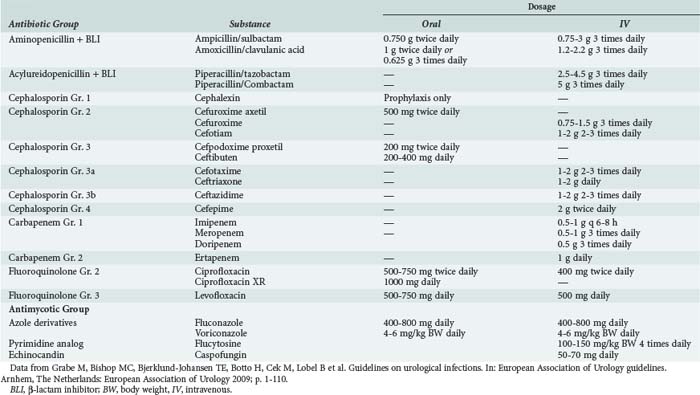

Multiple antimicrobial agents are available for therapy for complicated UTI (Table 133-3): second- or third-generation cephalosporins, broad-spectrum penicillins with β-lactamase inhibitors, monobactams, and carbapenems. For empirical therapy for severe UTI, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be used (e.g., broad-spectrum penicillins with β-lactamase inhibitors, third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, or carbapenems). Synergism with aminoglycosides, which inhibit protein synthesis and thus block the forming of toxins or virulence factors, might be useful for initial therapy, but side effects have to be considered.

TABLE 133-3 Division and Dosage of Distinct Antibiotics Recommended for Treatment of Urinary Tract Infections

Candiduria is a common problem in ICUs. It may represent harmless colonization, but it can also be an early sign of systemic candidosis.18 A second urine culture after exchanging the urethral catheter can rule out contamination. In the critically ill patient, systemic therapy for Candida species should be started according to susceptibility testing or species differentiation (see Table 133-3). Complicating factors such as diabetes mellitus or urologic abnormalities should be treated concomitantly. Systemic antimycotic therapy is preferred to local instillation therapy because of the potentially systemic nature of candiduria in ICU patients.

Prophylaxis of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

Silver coating of catheters may exert a bactericidal effect, but the concentration of free silver ions must be high, whereas the exposure to albumin and chloride ions has to be low, because silver-chloride complexes can precipitate.19 Heparin-coated catheters also demonstrate promising results. Suprapubic catheterization can initially decrease the rate of UTI from 40% to 18%, because the proximity to the anal region as well as the irritation of the urethral mucosa with ensuing mucopurulent discharge are avoided.8 Urinary drainage should be performed with a closed system that should not be opened either for emptying or for urinary sampling. The sites used for urinary sampling must be adequately sterilized. A rigid vertical, ventilated, drop chamber should be available to prevent encrustation.20 General hygienic procedures such as aseptic catheter insertion, wearing of disposable gloves, and hygienic hand disinfection to prevent cross-contamination or cross-infection are mandatory. International consensus recommendations for the use of urinary catheters to prevent healthcare-associated infections have been recently described.21

Recommended Evidence-Based Measurements For Preventing Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

The primary methodologies for preventing catheter-associated UTIs21 include:

Special Clinical Issues

Special Clinical Issues

Infections of the Upper Urinary Tract and Contiguous Organs

Pyelonephritis

The high osmolality of the renal medulla has a negative effect on leukocyte function. For that reason, the interstitium of the renal medulla is much more affected in pyelonephritis than the cortex is. Clinical symptoms are unilateral or bilateral flank pain, painful micturition, dysuria, and fever (>38°C). Focal nephritis is limited to one or more renal lobules, comparable to lobular pneumonia. Ultrasonographic findings are of a circumscribed lesion with interrupted echoes that break through the normal cortex/medulla organization. Computed tomography (CT) scan shows typical wedge-shaped, poorly limited areas of diminished sonographic density. As differential diagnoses, renal abscess, tumor, and renal infarction must be taken into account. Emphysematous pyelonephritis characteristically shows gas formation in the renal parenchyma and perirenal space. Diabetes mellitus or obstructive renal disease are predisposing factors. The most frequently isolated organisms are E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterobacter cloacae. Fermentation of glucose in Enterobacteriaceae occurs via two different metabolic pathways: mixed acid fermentation and the butylene glycol pathway. Organisms of the Klebsiella-Enterobacter-Hafnia-Serratia group, and to a lesser extent E. coli, use the butylene glycol pathway and produce copious amounts of CO2, which appears clinically as gas formation.22 Aggravated by diminished tissue perfusion, the contralateral side is often affected as well.

Renal and Perirenal Abscess

Clinical symptoms are rigors, fever, back or abdominal pain, flank tenderness, mass lesion and redness of the flank, and protection of upper lumbar and paraspinal muscles. Respiratory insufficiency, hemodynamic instability, or reflectory paralytic ileus occurs frequently. Frequent signs of renal abscess formation are fever and leukocytosis for more than 72 hours, despite antibiotic therapy. Urinary culture may be negative in 14% to 20%.23 Frequently isolated organisms are E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Proteus spp., and Staphylococcus aureus from hematogenous spread. Caudad, the fascial limitations are open, and the perirenal fat is in close contact with the pelvic fat tissue. A perinephritic abscess may therefore point to groin or perivesical tissue or to the contralateral side, thus penetrating the peritoneum. Inflammation of flank, thigh, back, buttocks, and lower abdomen may occur. Because of late diagnosis, the mortality can be as high as 57%. Blood cultures are positive in 10% to 40%, and urinary cultures are positive in 50% to 80%.24

Infections of the Lower Urinary Tract and Contiguous Organs

Cystitis

Cystitis is frequently limited to the bladder mucosa and hence shows no systemic signs or symptoms. An ascending infection can, however, clinically result. Cystitis in the ICU is almost exclusively catheter associated and can cause hematuria. Spontaneous elimination is frequently found after removal of the indwelling catheter, but less frequently in elderly patients.4

Acute Prostatitis and Prostatic Abscess

Acute prostatitis and prostatic abscess are bacterial infections of the prostate gland. The bacterial spectrum consists of 53% to 80% E. coli and other enterobacteria, 19% gram-positive bacteria, and 17% anaerobic bacteria.25 In regions with a high incidence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, the prostate may be involved. Symptoms are high fever, rigors, dysuria, urinary retention, and perineal pain. Rectal palpation reveals an enlarged, tender prostate. Prostate massage is contraindicated. In acute prostatitis, the pathogens are usually detected in urine. However, the urine may be sterile in prostatic abscess formation. Therapy consists of a combination of antibiotic therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics, as well as insertion of a suprapubic catheter. In the case of a prostatic abscess, urologic drainage is necessary.25

Fournier’s Gangrene

Fournier’s gangrene is a necrotizing fasciitis of the dartos and Colles fascias. It is mainly seen in men in the fourth to seventh decade but also occurs in women or the newborn. Causes are operations or trauma in the genital or perineal region, including microlesions, or infectious processes from the rectal or urethral areas. Important predisposing factors are diabetes mellitus, liver insufficiency, chronic alcoholism, hematologic diseases, or malnutrition. Patient-related predictors of mortality are increasing age, increased Charlson comorbidity index, preexisting conditions such as congestive heart failure, renal failure or coagulopathy, and hospital admission via transfer.26 Fatality rates nowadays were 7.5% in one large study.27 The infectious process follows anatomically preformed spaces. The superficial perineal fascia is fixed dorsally at the transverse deep perineal muscle and laterally at the iliac bone and merges ventrally in the superficial abdominal fascia. Hence, a ventrally open and craniodorsally and laterally closed space is formed (Colles space) that facilitates the spread of infection. In contrast to gas gangrene, the fascial borders are respected in Fournier’s gangrene. A mixed bacterial flora is seen, consisting of gram-positive cocci, enterobacteria, and anaerobic bacteria. The released toxins facilitate platelet aggregation and activation of complement, which in conjunction with the release of heparinase by anaerobic bacteria, leads to small vessel thrombosis and tissue necrosis. The destruction of tissue enhances the potential of acute renal failure. Fournier’s gangrene is a rapidly progressing infection leading to septic shock if not treated in time.

Urosepsis

Immediately after microbiological sampling of urine and blood, empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy should be started parenterally. Adequate initial (e.g., in the first hour) antibiotic therapy ensures improved outcome in septic shock.28,29 Inappropriate antimicrobial therapy in severe UTI is linked to a higher mortality rate,30 as it has been shown with other infections as well.31,32 Empirical antibiotic therapy therefore needs to follow rules33 which are based upon the expected bacterial spectrum, institutional-specific resistance rates, specific pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors in UTI, and individual patient characteristics.

The bacterial spectrum in urosepsis predominantly consists of enterobacteria such as E. coli, Proteus spp., Enterobacter and Klebsiella spp., non-fermenting organisms such as P. aeruginosa, and also gram-positive organisms.34–36 Candida spp. and Pseudomonas spp. occur as causative agents in urosepsis mainly if host defense is impaired.37 Patients with candiduria also show frequently invasive candidiasis and candidemia.38,39 Candiduria at any time in an ICU is associated with higher mortality rates (OR, 2.86).39 Viruses are not common causes of urosepsis.

Although urosepsis is a systemic disease, the activity of an antibiotic at the site of the infection is critical. A variety of studies show that inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, CXC chemokines, endotoxin, or HMGB1 are produced and released in the urinary tract.40–43 Therefore predominantly antimicrobial substances with a high activity in the urogenital tract are recommended.44,45

The increasing antibiotic resistance rates of pathogens causing urosepsis significantly diminish the choice of antibiotics available for adequate empirical initial treatment in urosepsis. In particular, the increasing rates of Enterobacteriaceae producing ESBL pose clinically relevant problems.46–48 Other recent developments of concern include increased rates of fluoroquinolone-resistant enterobacteria and vancomycin-resistant enterococci.49,50 There are no specific pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters yet available for the treatment of uroseptic patients.

Correct dosing in urosepsis has to consider the altered systemic and especially renal pathophysiology that exists in patients with urosepsis. Sepsis and the treatment thereof result in higher clearances of antibacterial drugs.51 The increased volume of distribution as a result of peripheral edema in sepsis will lead to underexposure, especially of hydrophilic antimicrobials such as β-lactams and aminoglycosides, which exhibit a volume of distribution mainly restricted to the extracellular space.52 Urosepsis may also cause multiple organ dysfunction such as hepatic or renal dysfunction, resulting in decreased clearance of antibacterial drugs. Increased dosing is therefore necessary. As β-lactams are time-dependent antibacterials, optimal administration would be by continuous infusion. In one study, an area under the antibiotic concentration time curve (AUIC) ≥ 250 and time over the minimal inhibitory concentration (T > MIC) = 100% has been associated with treatment success.53 Fluoroquinolones, on the other hand, display largely concentration-dependent activity. The volume of distribution of fluoroquinolones in sepsis is not greatly influenced by fluid shifts, and therefore no alterations of standard doses are necessary unless renal dysfunction occurs.51

Depending on local susceptibility patterns, a third-generation cephalosporin such as piperacillin in combination with a β-lactamase inhibitor (BLI) or carbapenem may be appropriate for empirical treatment.4,53–57 In areas with a high (>10%) rate of Enterobacteriaceae producing ESBL, initial treatment with a carbapenem might be advisable.54–58 Aminoglycosides as monotherapy might be an alternative; however, the data supporting monotherapy in uroseptic patients are not sufficient.59 In case of candiduria with signs of sepsis, antifungal treatment is recommended.38,39

Key Points

Goto T, Nakame Y, Nishida M, Ohi Y. Bacterial biofilms and catheters in experimental urinary tract infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;11:227-231.

Grabe M, Bishop MC, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, Botto H, Cek M, Lobel B, et al. Guidelines on urological infections. In: European Association of Urology guidelines. Arnhem, The Netherlands: European Association of Urology; 2009:1-110.

Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:625-663.

Oliver A, Cantón R, Campo P, et al. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science. 2000;288:1251-1253.

Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302:2323-2329.

1 Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009 Dec 2;302(21):2323-2329.

2 Wagenlehner FM, Loibl E, Vogel H, Naber KG. Incidence of nosocomial urinary tract infections on a surgical intensive care unit and implications for management. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006 Aug;28(Suppl 1):S86-S90.

3 Naber KG. Urogenital infections: The pivotal role of the urologist. Eur Urol. 2006 Oct;50(4):657-659.

4 Grabe M, Bishop MC, Bjerklund-Johansen TE, Botto H, Cek M, Lobel B, et al. Guidelines on urological infections. In: European Association of Urology guidelines. Arnhem, The Netherlands: European Association of Urology; 2009:1-110.

5 Bjerklund Johansen TE, Cek M, Naber K, Stratchounski L, Svendsen MV, Tenke P. Prevalence of hospital-acquired urinary tract infections in urology departments. Eur Urol. 2007 Apr;51(4):1100-1112.

6 Chen SL, Jackson SL, Boyko EJ. Diabetes mellitus and urinary tract infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis and proposed studies in animal models. J Urol. 2009 Dec;182(6 Suppl):S51-S56.

7 Elhilali MM, Hassouna M, Abdel-Hakim A, Teijeira J. Urethral stricture following cardiovascular surgery: role of urethral ischemia. J Urol. 1986 Feb;135(2):275-277.

8 Horgan AF, Prasad B, Waldron DJ, O’Sullivan DC. Acute urinary retention. Comparison of suprapubic and urethral catheterisation. Br J Urol. 1992 Aug;70(2):149-151.

9 Warren JW, Tenney JH, Hoopes JM, Muncie HL, Anthony WC. A prospective microbiologic study of bacteriuria in patients with chronic indwelling urethral catheters. J Infect Dis. 1982 Dec;146(6):719-723.

10 LeClerc JE, Li B, Payne WL, Cebula TA. High mutation frequencies among Escherichia coli and Salmonella pathogens. Science. 1996 Nov 15;274(5290):1208-1211.

11 Oliver A, Canton R, Campo P, Baquero F, Blazquez J. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science. 2000 May 19;288(5469):1251-1254.

12 Costerton JW. Introduction to biofilm. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999 May;11(3-4):217-221. discussion 37-9

13 Reid G. Biofilms in infectious disease and on medical devices. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999 May;11(3-4):223-226. discussion 37-9

14 Goto T, Nakame Y, Nishida M, Ohi Y. Bacterial biofilms and catheters in experimental urinary tract infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999 May;11(3-4):227-231. discussion 37-9

15 Aspevall O, Hallander H, Gant V, Kouri T. European guidelines for urinalysis: a collaborative document produced by European clinical microbiologists and clinical chemists under ECLM in collaboration with ESCMID. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001 Apr;7(4):173-178.

16 Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008 Jun;36(5):309-332.

17 Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Mar 1;40(5):643-654.

18 Nassoura Z, Ivatury RR, Simon RJ, Jabbour N, Stahl WM. Candiduria as an early marker of disseminated infection in critically ill surgical patients: the role of fluconazole therapy. J Trauma. 1993 Aug;35(2):290-294. discussion 4-5

19 Schierholz JM, Lucas LJ, Rump A, Pulverer G. Efficacy of silver-coated medical devices. J Hosp Infect. 1998 Dec;40(4):257-262.

20 Drehsen U, Schumacher M, Daschner F. Vergleichende Prüfung von geschlossenen Urindrainagesystemen mit Urimeter. Hyg Med. 1998;23:204-210.

21 Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, Colgan R, Geerlings SE, Rice JC, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(5):625-663.

22 Koneman EW, Allen SD, Janda WM, Schreckenberger PC, Winn WC. Enterobacteriaceae: Carbohydrate utilization. In: Koneman EW, Allen SD, Janda WM, Schreckenberger PC, Winn WC, editors. Diagnostic Microbiology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1997:172-176.

23 Elkin M. Renal cystic disease–an overview. Semin Roentgenol. 1975 Apr;10(2):99-102.

24 Sheinfeld J, Erturk E, Spataro RF, Cockett AT. Perinephric abscess: current concepts. J Urol. 1987 Feb;137(2):191-194.

25 Naber KG, Wagenlehner FME, Weidner W. Acute bacterial prostatitis. In: Shoskes DA, editor. Current Clinical Urology Series, Chronic Prostatitis/ Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Totowa, NJ: Humana press; 2008:17-30.

26 Sorensen MD, Krieger JN, Rivara FP, Klein MB, Wessells H. Fournier’s gangrene: management and mortality predictors in a population based study. J Urol. 2009 Dec;182(6):2742-2747.

27 Sorensen MD, Krieger JN, Rivara FP, Broghammer JA, Klein MB, Mack CD, et al. Fournier’s Gangrene: population based epidemiology and outcomes. J Urol. 2009 May;181(5):2120-2126.

28 Kreger BE, Craven DE, McCabe WR. Gram-negative bacteremia. IV. Re-evaluation of clinical features and treatment in 612 patients. Am J Med. 1980 Mar;68(3):344-355.

29 Kreger BE, Craven DE, Carling PC, McCabe WR. Gram-negative bacteremia. III. Reassessment of etiology, epidemiology and ecology in 612 patients. Am J Med. 1980 Mar;68(3):332-343.

30 Elhanan G, Sarhat M, Raz R. Empiric antibiotic treatment and the misuse of culture results and antibiotic sensitivities in patients with community-acquired bacteraemia due to urinary tract infection. J Infect. 1997 Nov;35(3):283-288.

31 Kollef MH, Ward S. The influence of mini-BAL cultures on patient outcomes: implications for the antibiotic management of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 1998 Feb;113(2):412-420.

32 Luna CM, Vujacich P, Niederman MS, Vay C, Gherardi C, Matera J, et al. Impact of BAL data on the therapy and outcome of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 1997 Mar;111(3):676-685.

33 Singh N, Yu VL. Rational empiric antibiotic prescription in the ICU. Chest. 2000 May;117(5):1496-1499.

34 Menninger M. Urosepsis, Klinik, Diagnostik und Therapie. In: Hofstetter A, editor. Urogenitale Infektionen. Berlin Heidelberg. New York: Springer; 1998:521-528.

35 Rosenthal EJ. [Epidemiology of septicaemia pathogens]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2002 Nov 15;127(46):2435-2440.

36 Wagenlehner FM, Pilatz A, Naber KG, Weidner W. Therapeutic challenges of urosepsis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008 Oct;38(Suppl 2):45-49.

37 Johansen TE, Cek M, Naber KG, Stratchounski L, Svendsen MV, Tenke P. Hospital acquired urinary tract infections in urology departments: pathogens, susceptibility and use of antibiotics. Data from the PEP and PEAP-studies. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006 Aug;28(Suppl 1):S91-107.

38 Binelli CA, Moretti ML, Assis RS, Sauaia N, Menezes PR, Ribeiro E, et al. Investigation of the possible association between nosocomial candiduria and candidaemia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006 Jun;12(6):538-543.

39 Magill SS, Swoboda SM, Johnson EA, Merz WG, Pelz RK, Lipsett PA, et al. The association between anatomic site of Candida colonization, invasive candidiasis, and mortality in critically ill surgical patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006 Aug;55(4):293-301.

40 McAleer IM, Kaplan GW, Bradley JS, Carroll SF, Griffith DP. Endotoxin content in renal calculi. J Urol. 2003 May;169(5):1813-1814.

41 Olszyna DP, Opal SM, Prins JM, Horn DL, Speelman P, van Deventer SJ, et al. Chemotactic activity of CXC chemokines interleukin-8, growth-related oncogene-alpha, and epithelial cell-derived neutrophil-activating protein-78 in urine of patients with urosepsis. J Infect Dis. 2000 Dec;182(6):1731-1737.

42 European Association of Urology guidelines. Available at: http://www.uroweb.org/guidelines/copyright-and-republication/how-to-reference-the-eau-guidelines/

43 van Zoelen MA, Laterre PF, van Veen SQ, van Till JW, Wittebole X, Bresser P, et al. Systemic and local high mobility group box 1 concentrations during severe infection. Crit Care Med. 2007 Dec;35(12):2799-2804.

44 Wagenlehner FM, Weidner W, Naber KG. Optimal management of urosepsis from the urological perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007 Nov;30(5):390-397.

45 Wagenlehner FM, Weidner W, Naber KG. Pharmacokinetic characteristics of antimicrobials and optimal treatment of urosepsis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007;46(4):291-305.

46 Ho PL, Chan WM, Tsang KW, Wong SS, Young K. Bacteremia caused by Escherichia coli producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase: a case-control study of risk factors and outcomes. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34(8):567-573.

47 Kizirgil A, Demirdag K, Ozden M, Bulut Y, Yakupogullari Y, Toraman ZA. In vitro activity of three different antimicrobial agents against ESBL producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae blood isolates. Microbiol Res. 2005;160(2):135-140.

48 Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. Mortality and delay in effective therapy associated with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in Enterobacteriaceae bacteraemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007 Nov;60(5):913-920.

49 Chou YY, Lin TY, Lin JC, Wang NC, Peng MY, Chang FY. Vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia: comparison of clinical features and outcome between Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008 Apr;41(2):124-129.

50 Nguyen LH, Hsu DI, Ganapathy V, Shriner K, Wong-Beringer A. Reducing empirical use of fluoroquinolones for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections improves outcome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008 Mar;61(3):714-720.

51 Roberts JA, Lipman J. Antibacterial dosing in intensive care: pharmacokinetics, degree of disease and pharmacodynamics of sepsis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45(8):755-773.

52 Pea F, Pavan F, Di Qual E, Brollo L, Nascimben E, Baldassarre M, et al. Urinary pharmacokinetics and theoretical pharmacodynamics of intravenous levofloxacin in intensive care unit patients treated with 500 mg b.i.d. for ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Chemother. 2003 Dec;15(6):563-567.

53 Nicolle LE, Madsen KS, Debeeck GO, Blochlinger E, Borrild N, Bru JP, et al. Three days of pivmecillinam or norfloxacin for treatment of acute uncomplicated urinary infection in women. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34(7):487-492.

54 Bin C, Hui W, Renyuan Z, Yongzhong N, Xiuli X, Yingchun X, et al. Outcome of cephalosporin treatment of bacteremia due to CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006 Dec;56(4):351-357.

55 Byl B, Clevenbergh P, Kentos A, Jacobs F, Marchant A, Vincent JL, et al. Ceftazidime- and imipenem-induced endotoxin release during treatment of gram-negative infections. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001 Nov;20(11):804-807.

56 Kuo BI, Fung CP, Liu CY. Meropenem versus imipenem/cilastatin in the treatment of sepsis in Chinese patients. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 2000 May;63(5):361-367.

57 Luchi M, Morrison DC, Opal S, Yoneda K, Slotman G, Chambers H, et al. A comparative trial of imipenem versus ceftazidime in the release of endotoxin and cytokine generation in patients with gram-negative urosepsis. Urosepsis Study Group. J Endotoxin Res. 2000;6(1):25-31.

58 Alhambra A, Cuadros JA, Cacho J, Gomez-Garces JL, Alos JI. In vitro susceptibility of recent antibiotic-resistant urinary pathogens to ertapenem and 12 other antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004 Jun;53(6):1090-1094.

59 Ludwig M, Vidal A, Diemer T, Pabst W, Failing K, Weidner W. Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome): seminal markers of inflammation. World J Urol. 2003 Jun;21(2):82-85.

60 Gordon KA, Jones RN. Susceptibility patterns of orally administered antimicrobials among urinary tract infection pathogens from hospitalized patients in North America: comparison report to Europe and Latin America. Results from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2000). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003 Apr;45(4):295-301.

61 Bouza E, San Juan R, Munoz P, Voss A, Kluytmans J. A European perspective on nosocomial urinary tract infections I. Report on the microbiology workload, etiology and antimicrobial susceptibility (ESGNI-003 study). European Study Group on Nosocomial Infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001 Oct;7(10):523-531.