Infections of the Spine and Spinal Cord

Spinal infections in children are uncommon. Etiologies include direct and indirect (hematogenous) inoculation by bacterial, viral, parasitic, and fungal agents. Direct bacterial infectious inoculation may occur as a result of trauma, instrumentation, or via a preexisting congenital sinus tract or area of spinal dysraphism (i.e., a meningocele). In recent years, Lyme disease (Fig. 44-1) caused by a Borrelia burgdorferi infected tick bite has emerged as a cause of spinal cord infection, especially in the Northeastern United States. Mosquito-borne West Nile virus (Fig. 44-2), with cases initially appearing along the east coast of the United States, has since been discovered nationwide and also has emerged as a more recent spinal cord infectious agent. Tuberculosis (TB) of the spinal cord usually occurs in the thoracic region in children (Fig. 44-3) and manifests as an intramedullary tuberculoma, most often seen in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome or other types of immunocompromise. TB is most prevalent in India, but it is also widespread in Africa and in Southeast Asia. Cysticercosis (Fig. 44-4) is the most common parasitic infection encountered within the spinal cord. It occurs after ingestion of uncooked pork infected with Taenia solium and is most prevalent in South America and Southeast Asia. Gnathostomiasis (Fig. 44-5) is caused by the nematode Gnathostoma spinigerum, which is acquired by ingesting contaminated fish or meat and presents clinically with myeloradiculitis. It is endemic in Southeast Asia and virtually unknown in North America, other than in persons with infections that are acquired abroad.

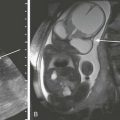

Figure 44-1 An adult who was bitten by a tick and infected with Lyme disease.

Sagittal (A) and axial (B) T2-weighted images of the cervical spine demonstrate T2 prolongation (asterisks in A and arrows in B) within the dorsal spinal cord at the level of C5/C6 as a result of demyelination. (Case courtesy Gul Moonis, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Division of Neuroradiology.)

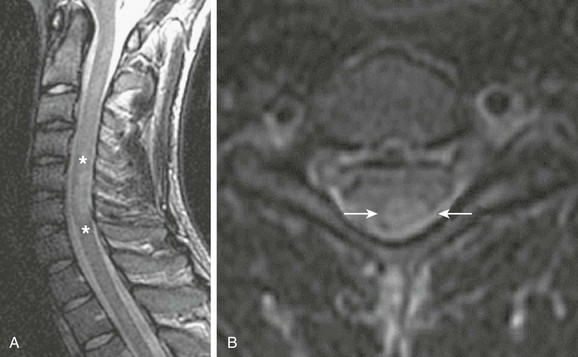

Figure 44-2 An adult patient who was bitten by a mosquito and infected with West Nile virus.

Sagittal and axial T2-weighted images (A and C, respectively), and sagittal (B) and axial (D and E) postgadolinium T1-weighted images of the lumbar spine demonstrate T2 prolongation (A, asterisks, and C, arrows) within the distal spinal cord/conus medullaris, as well as contrast enhancement of the distal cord (B, asterisks)/conus medullaris (D, arrows) and within the cauda equina (E, arrows) as a result of viral myeloradiculitis. (Case courtesy Gul Moonis, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Division of Neuroradiology.)

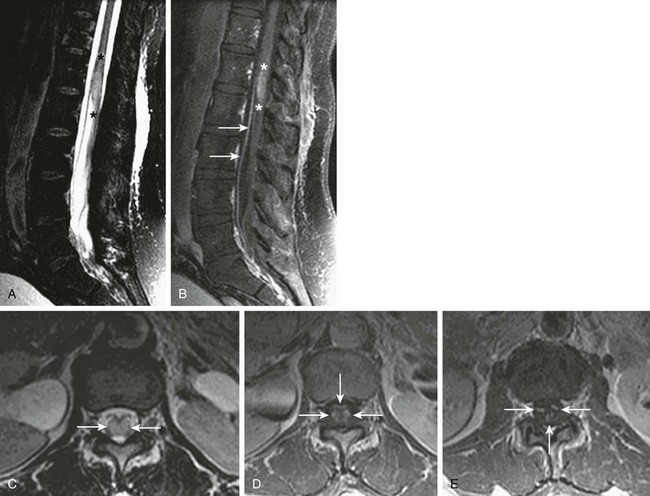

Figure 44-3 An adult patient with tuberculosis exposure.

Axial postcontrast T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (A) and thoracic spine (B) demonstrate multiple enhancing intraaxial nodules corresponding to tuberculomas (arrows in B). (Case courtesy Drs. Pranjal Goswami, Nirod Medhi, and Pratul Kr. Sarma of Primus Institute in Guwahati, India.)

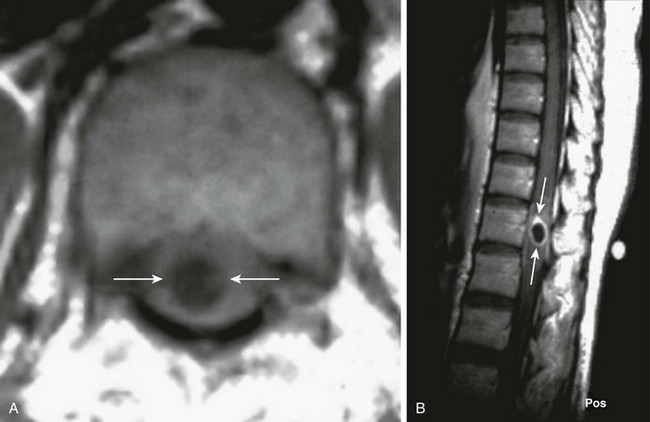

Figure 44-4 A 20-year-old man who presented with paraparesis that developed over a few weeks was found to have cysticercosis.

An axial T1-weighted image (A) and a sagittal postcontrast T1-weighted image (B) of the thoracic spine demonstrate central T1 prolongation within the spinal cord proper (arrows in A), with corresponding rim enhancement on the postcontrast image (arrows in B). (Case courtesy Dr. Manu Shroff of the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada.)

Figure 44-5 A 17-year-old boy from Thailand with gnathostomiasis.

Sagittal (A) and axial (B) postcontrast T1-weighted images of the thoracic spine demonstrate enhancing nodules (arrows in A and B) within the spinal cord proper as a result of a parasitic infection. (Case courtesy Dr. Jiraporn Laothamatas of Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand.)

Discitis and Osteomyelitis

Disc space infection often coexists with vertebral osteomyelitis in children as a result of hematogenous spread through capillary tufts in vertebral body endplates and vascular channels of immature intervertebral disc spaces. Contrast-enhanced MRI is the study of choice and should be performed without delay in suspected cases (Fig. 44-6). Although infection can occur at any level, the midlumbar spine is most often affected. Staphylococcus aureus represents the most common etiologic organism. Worldwide, organisms such as TB are not uncommon etiologies. The first radiographic sign of infection is irregularity of the vertebral body endplates. The affected disc space is usually narrowed and demonstrates low signal intensity on T2-weighted MR sequences. Edema and postcontrast enhancement in adjacent vertebral body endplates indicate the presence of associated osteomyelitis and possible disc space abscess. Complicated cases demonstrate epidural and paravertebral abscess or phlegmon, which are well elucidated by MRI. Signs of late infection include vertebral body collapse and spinal deformity (Fig. 44-7). After treatment, vertebral body and disc space findings may persist for up to 24 and 34 months, respectively. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis is the most severe form of chronic nonbacterial osteomyelitis and is of uncertain etiology. Although chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis most commonly affects the metaphyses of long bones and the medial clavicles, vertebral column and pelvic involvement can occur.

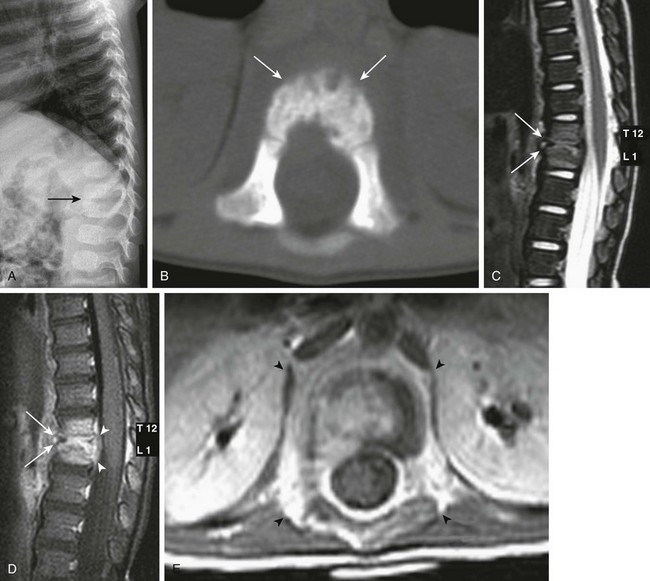

Figure 44-6 A 15-month-old girl with abnormal gait and concern for an intraspinal mass had discitis/osteomyelitis.

Lateral spine radiographs demonstrate narrowing of the T12-L1 intervertebral disc space (arrow in A). An axial bone window from a noncontrast computed tomography scan of the spine demonstrates irregularity to the vertebral endplates (arrows in B). A sagittal T2-weighted image (C), a sagittal fat-saturated T1-weighted postcontrast image (D), and an axial T1-weighted postcontrast image (E) of the thoracolumbar junction demonstrate loss of height of the T12-L1 intervertebral disc space with adjacent T2 prolongation of the adjacent endplates (arrows in C), with corresponding abnormal enhancement in the same regions (arrows in D), and surrounding masslike soft tissue enhancement (arrowheads in E). Note the thickening/elevation and enhancement of the posterior longitudinal ligament (arrowheads in D).

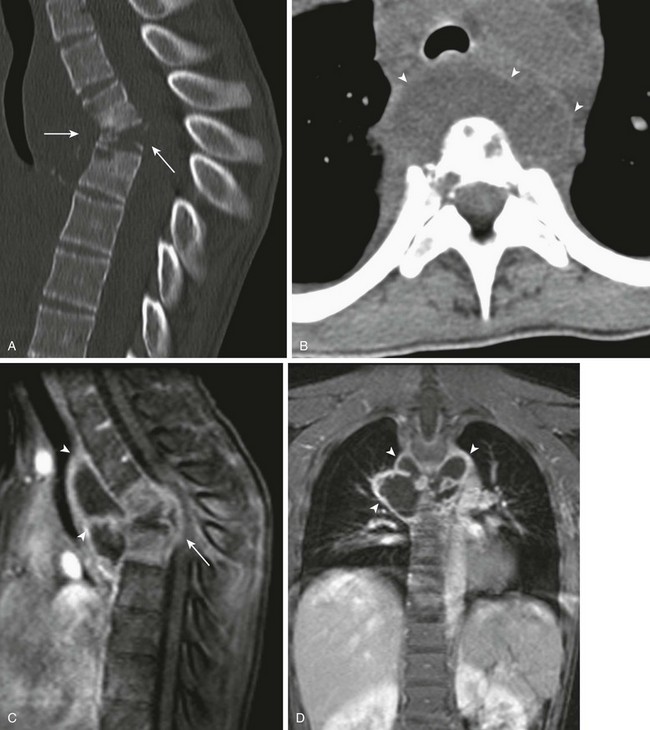

Figure 44-7 A 13-year-old girl with progressive loss of strength and coordination in legs had tuberculous osteomyelitis.

Sagittal midline bone reformation (A) and an axial soft-tissue window (B) from noncontrast computed tomography of the spine, as well as sagittal (C) and coronal (D) fat-saturated T1-weighted postcontrast images of the thoracic spine demonstrate marked kyphosis at the site of bony collapse at the level of the midthoracic spine (arrows in A and C), as well as a surrounding soft tissue abscess (arrowheads in B, C, & D), predominately anteriorly, at the same level.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

Since the eradication of poliomyelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) (Fig. 44-8), or acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, has become the most common cause of acute motor paralysis in children. It is believed to arise from an abnormal T-cell response precipitated by a preceding infection. Infectious etiologies include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis, varicella, Mycoplasma pneumonia, and Campylobacter jejuni. MRI often shows thickening of the cauda equina and intrathecal nerve roots, as well as anterior predominant nerve root gadolinium enhancement, even beyond the period of the initial presentation. Imaging findings have been described to be 83% sensitive for acute GBS and are present in 95% of typical cases. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (Fig. 44-9) is thought to be a chronic form of GBS that shares in these imaging characteristics, but it often shows marked nerve root thickening.

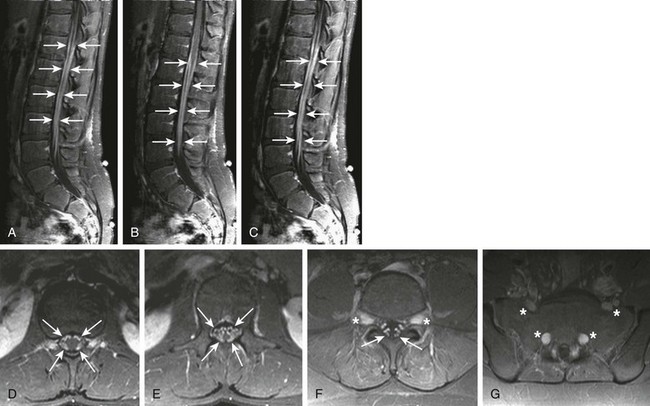

Figure 44-8 A patient who was unable to ambulate had Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Sagittal off-midline and midline postgadolinium T1-weighted fat-saturated images through the lumbar spine (A and B), and axial postcontrast T1-weighted images through the conus medullaris and proximal lumbar nerve roots (C and D) demonstrate extensive contrast enhancement of nerve roots (arrows), particularly anteriorly, typical of Guillain-Barré syndrome.

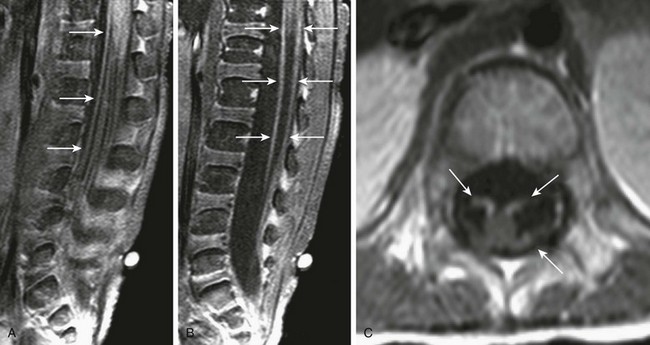

Figure 44-9 A 13-year-old boy with peripheral neuropathy and gait disturbances was found to have chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP).

Sagittal fat-saturated T1-weighted images off-midline to the right, at midline, and off-midline to the left (A, B, and C, respectively) and axial postcontrast T1-weighted fat-saturated images through the lower thoraco-lumbar junction, conus medullaris, proximal nerve roots, and distal nerve roots (D, E, F, and G, respectively) demonstrate marked enhancement of the spinal nerve roots (arrows), with expansion of the nerve roots seen as they exit the neural foramina, best seen in F and G (asterisks). This enlargement and enhancement is typical of CIDP.

Transverse Myelitis

Transverse myelitis (TM) is an inflammatory condition that traverses a focal area of the spinal cord. In children, it most often occurs after the age of 10 years. The midthoracic spine is most often affected, and patients present with symmetrical bilateral sensory and motor deficits related to the affected regions. Although viral etiologies are believed to be the leading infectious cause of TM, as many as 60% of cases are thought to be idiopathic in nature. In most cases, a specific viral etiology is never determined. Vasculitides seen with autoimmune diseases such as lupus erythematosus also have been described as potential etiologies. TM manifests on MRI (Fig. 44-10) with increased T2 signal, encompassing more than two thirds of the spinal cord’s diameter on fluid-sensitive (T2-weighted) sequences, extending along several vertebral segments, with variable enlargement of the cord as a result of edema and variable degrees of contrast enhancement.

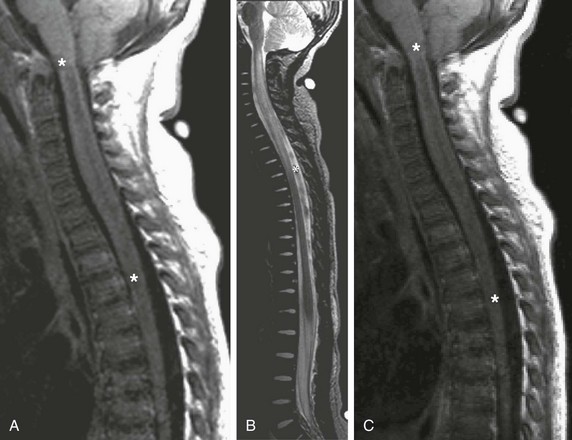

Figure 44-10 Fever and rapidly ascending paralysis in a 17-month-old boy with transverse myelitis.

Sagittal T1-weighted (A), sagittal T2-weighted (B), and sagittal postgadolinium T1-weighted (C) images demonstrate the diffuse T1 (A) and T2 (B) prolongation (asterisks) of the entire cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord, with associated expansion of the cervical cord. No associated contrast enhancement is noted (C) (asterisks).

Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is a monophasic focal or multifocal, perivascular inflammatory, and demyelinating disorder, which often presents after a vaccination or viral infection. These lesions often present as a diagnostic dilemma in which the differential diagnosis also includes neoplasm of the spinal cord and can in isolation often be indistinguishable from the demyelinating lesions of multiple sclerosis (MS). Normal apparent diffusion coefficients within the corpus callosum (brain) may aid in diagnosing acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, as opposed to MS, which classically demonstrates abnormal callosal apparent diffusion coefficients. A clinical history of a recent viral illness and/or vaccination is the key to properly diagnosing these lesions. Lesions generally are hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences and have corresponding hypointensity or isointensity on T1-weighted sequences (Fig. 44-11). Contrast enhancement is variable, with enhancement patterns including solid or ringlike enhancement to no enhancement at all in lesions that range from small to large, and which affect gray matter, white matter, or both. These lesions often show dramatic response to plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and immunoglobulin therapies, with consequent improvement or resolution of the imaging findings.

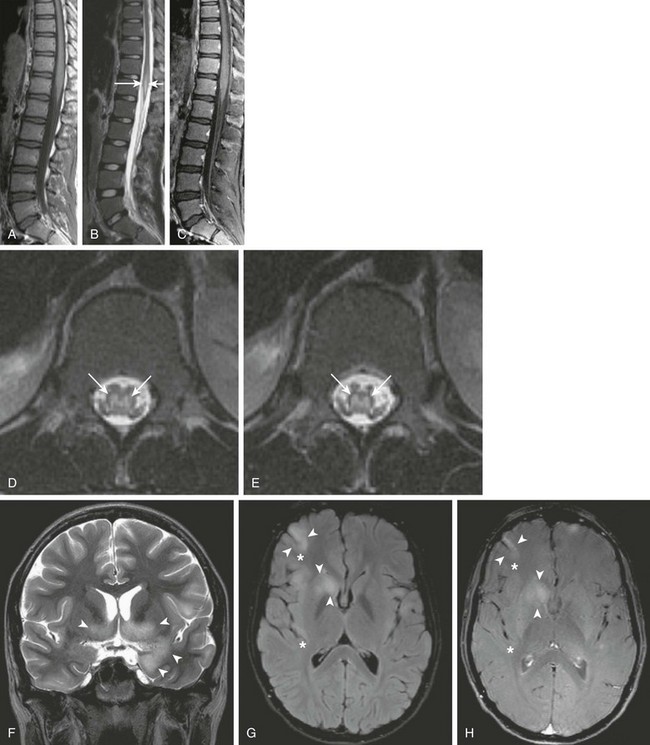

Figure 44-11 A 16-year-old boy with a history of constipation, urinary retention, and lower extremity weakness and numbness was found to have acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM).

Sagittal T1-weighted, sagittal T2-weighted, and sagittal postgadolinium T1-weighted images (A, B, and C, respectively), axial T2-weighted images through the lower thoraco-lumbar region (D and E), a coronal T2-weighted image of the brain (F), an axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery image through the brain (G), and an axial postcontrast magnetization transfer T1-weighted image through the brain (H) were obtained. Note the nonexpansive T2 prolongation (arrows) of the central spinal cord (D and E). In addition, areas of T2 prolongation are seen within the brain (F and G), with involvement of both superficial gray and deep gray structures (arrowheads), including the right insula (asterisks), in keeping with changes of ADEM.

Multiple Sclerosis

Although it is much more prevalent in the adult population, MS also is seen in the pediatric age group. The presentation and diagnosis in children mimics that seen in adults. Viral and immune diseases are believed to be the most common etiologies. Most patients affected by MS have spinal lesions. Spinal MS, which has a cervical cord predominance, is associated with concomitant brain lesions in 80% of cases, making brain imaging essential when it is a differential consideration. MS can involve the white as well as gray matter, and it usually manifests as eccentrically situated lesions involving the dorsolateral aspect of the spinal cord. The concomitant presence of optic neuritis, in addition to spinal cord involvement, constitutes what was previously known as Devic disease, now referred to as neuromyelitis optica. MRI, although nonspecific, is the gold standard in the diagnosis of MS and is seen to demonstrate disease in most patients presenting with clinical symptoms compatible with MS. MS lesions within the spinal cord usually span less than two vertebral bodies in length and demonstrate hypointense signal on T1-weighted images and a corresponding hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images (Fig. 44-12). Prompt contrast (gadolinium) enhancement occurs in active lesions. Fast short tau inversion imaging recovery sequences have greater sensitivity for lesion detection when compared with fast spin echo sequences.

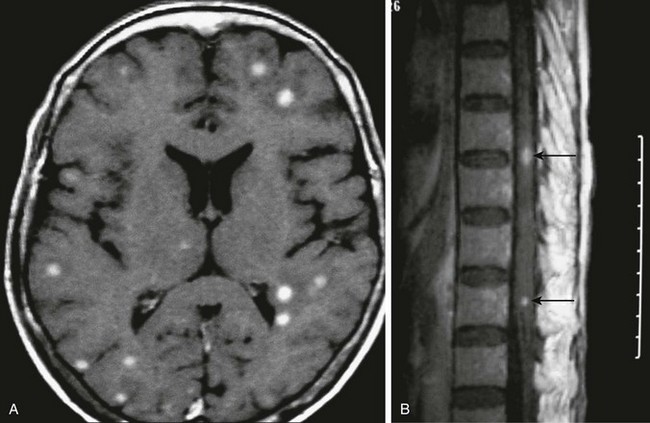

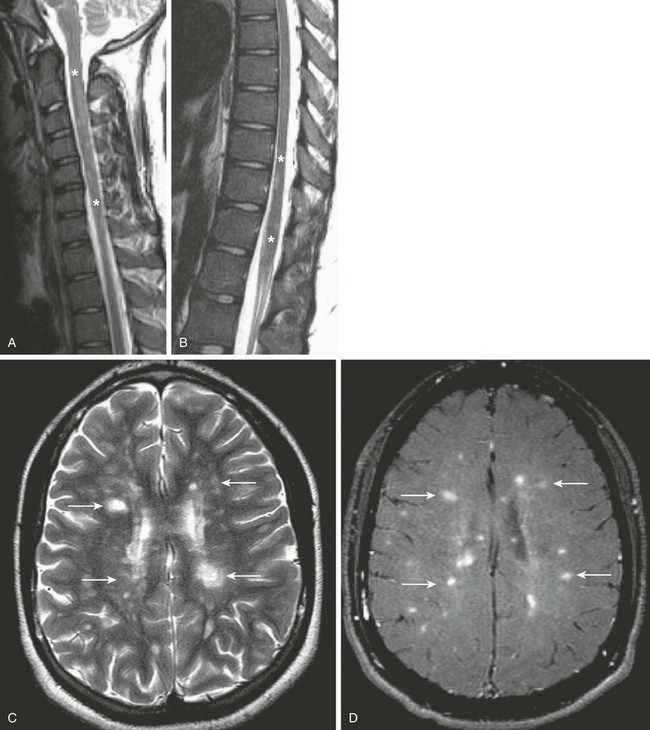

Figure 44-12 A child with sensory changes and decreased vision was found to have multiple sclerosis (MS).

Multiplanar T1- and T2-weighted images of the cervical and thoracic spinal cord and the brain were obtained, including sagittal T2-weighted images through the cervical and thoracic regions (A and B), as well as an axial T2-weighted image of the brain (C) and an axial postcontrast T1-weighted MT image of the brain (D). Note the nonexpansive T2 prolongation (asterisks) of the spinal cord (A and B). This finding is associated with multiple areas of T2 prolongation (arrows, C) within the deep white matter of the cerebrum, running perpendicular to the lateral ventricles (the so-called Dawson fingers), associated with enhancement (arrows, D), suggesting acuity to the demyelinating plaques, which is typical of the findings seen with MS.

Arabshahi, B, Pollock, AN, Sherry, DD. Devic disease in a child with primary Sjögren syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2006;21(4):285–286.

Brown, R, Hussain, M, McHugh, K, et al. Discitis in young children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:106–111.

Cameron, ML, Durack, DT. Helminthic infections. In: Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Durack DT, eds. Infections of the central nervous system. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1997.

Choi, KH, Lee, KS, Chung, SO, et al. Idiopathic tranverse myelitis: MR characteristics. Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17(6):1151–1160.

Coskun, A, Kumandas, S, Pac, A. Childhood Guillain-Barré syndrome. MR imaging in diagnosis and follow-up. Acta Radiol. 2003;44(2):230–235.

Dagirmanjian, A, Schils, J, McHenry, MC. MR imaging of spinal infections. Magn Reson Imag Clin North Am. 1999;7:525–538.

Ferguson, WR. Some observations on the circulation in fetal and infant spines. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32:640–648.

Fischer, GW, Popich, GA, Sullivan, DE, et al. Discitis: a prospective diagnostic analysis. Pediatrics. 1978;62:543–544.

Fuchs, PM, Meves, R, Yamada, HH. Spinal infections in children: a review. Int Orthop. 2012;36(2):387–395.

Goh, C, Phal, PM, Desmond, PM. Neuroimaging in acute transverse myelitis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2011;21(4):951–973.

Hughes, RA, Rees, JH. Clinical and epidemiological features of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:S92–S98.

Iyer, RS, Thapa, MM, Chew, FS. Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: review. AJR Integrative Imaging. 2011;196(suppl 2):S87–S91.

Kesselring, J, Miller, DH, Robb, SA. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. MRI findings and the distinction from multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1990;113(pt 2):291–302.

Khanna, G, Sato, TS, Ferguson, P. Imaging of chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis. Radiographics. 2009;29(4):1159–1177.

Kincaid, O, Lipton, HL. Viral myelitis: an update. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2006;6(6):469–474.

MacDonnell, AH, Baird, RW, Bronze, MS. Intramedullary tuberculomas of the spinal cord: case report and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:432–439.

Mahboubi, S, Morris, MC. Imaging of spinal infection of children. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39:215–222.

Mendonca, RA. Spinal infection and inflammatory disorders. In Atlas SW, ed.: Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, 3th ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

Noseworthy, JH, Lucchinetti, C, Rodriguez, M, et al. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(13):938–952.

Rocca, MA, Mastronardo, G, Horsfield, MA, et al. Comparison of three MR sequences for the detection of cervical cord lesions in patients with multiple sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(9):1710.

Ryan, MM. Guillain-Barré syndrome in childhood. J Paediatric Child Health. 2005;41(5-6):237–241.

Shalmon, B, Nass, D, Ram, Z, et al. Giant lesions in multiple sclerosis—a diagnostic challenge. Harefuah. 2000;138:936–939.

Singh, S, Alexander, M, Korah, IP. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:1101–1107.

Sithinamsuwan, P, Chairangsaris, P. Images in clinical medicine. Gnathostomiasis—neuroimaging of larval migration. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):188.

Straus Farber, R, Devilliers, L, Miller, A, et al. Differentiating multiple sclerosis from other causes of demyelination using diffusion weighted imaging of the corpus callosum. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30(4):732–736.