4 Infections of the Outer Eye

VIRAL INFECTIONS

ADENOVIRUS

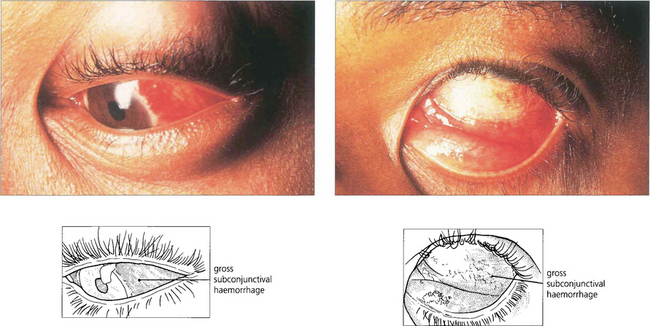

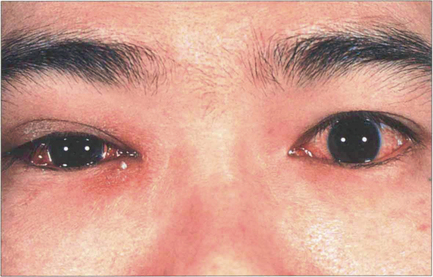

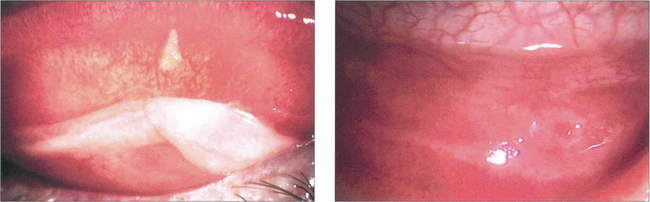

Fig. 4.1 Unilateral or asymmetrical lid swelling and conjunctival inflammation is typical of early infection.

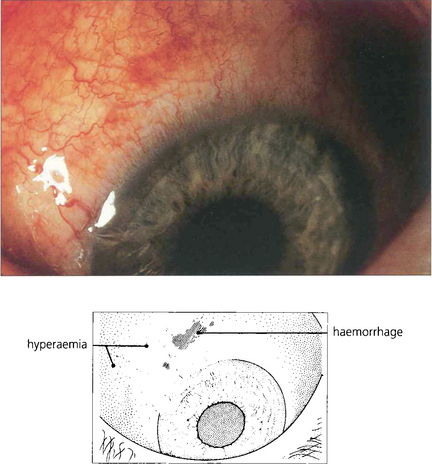

Fig. 4.2 The early stages of adenovirus conjunctivitis are often accompanied by a profuse watery discharge with marked hyperaemia of the bulbar conjunctiva. This patient also has small conjunctival haemorrhages which are sometimes present in the acute phase in patients with severe disease.

A typical case of moderate severity presents with acute bilateral but unequal, swelling and erythema of the eyelids associated with conjunctival inflammation and a watery serous discharge. There may be associated pre-auricular lymphadenopathy, a history of contact with other similar cases or a recent illness of the upper respiratory tract. Although the conjunctival changes resolve over 7–14 days, patients are often left with ocular irritation and discomfort for several weeks. This is due to tear film changes secondary to conjunctival scarring or keratitis.

Fig. 4.3 During the first few days, the palpebral conjunctiva is hyperaemic with a fine papillary reaction. Small amounts of mucopurulent discharge are often produced (right). Similar changes are visible over the upper tarsus (left) where, in severe cases, exudation of fibrin may combine with mucus and lead to pseudo-membrane formation.

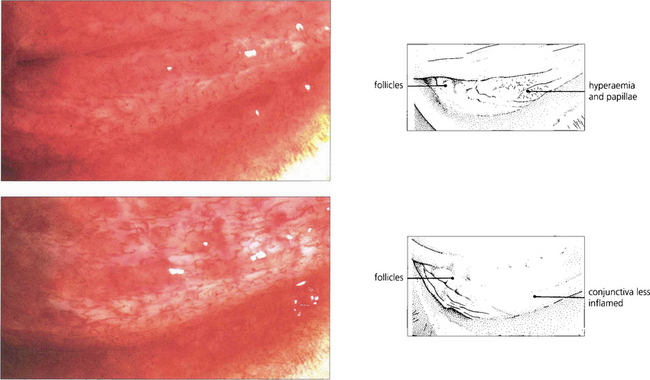

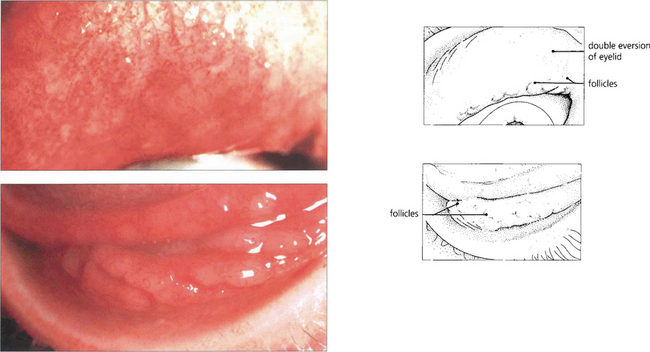

Fig. 4.4 During the first week, small follicles appear in the lower fornix and may later involve the tarsal surface. In the early stages, as in this example, the follicles are greyish-white with slightly raised areas appearing in the subepithelial layers of the inflamed conjunctiva (top). During the second week of the illness the follicles usually persist, although they become more discrete with resolution of the acute inflammatory changes found elsewhere in the conjunctiva. Appearance of the same eye 3 days later (bottom). By the second or third week, the conjunctival disease has usually resolved. The condition is self-limiting, although symptomatic relief may be obtained by the use of topical lubricants.

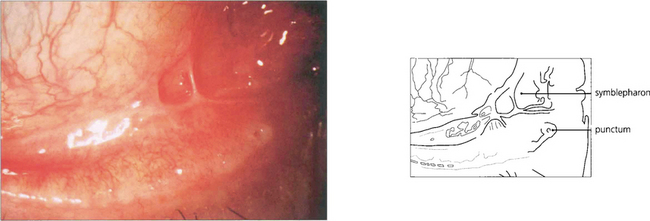

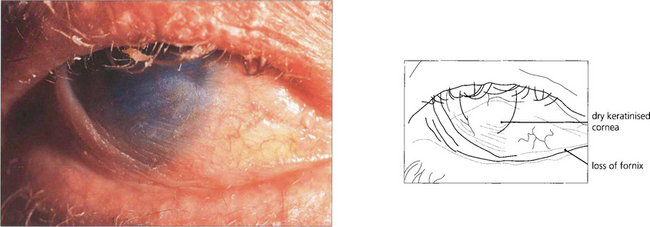

Fig. 4.5 In more severe infections, membranous conjunctivitis may result in sheet conjunctival scarring and symblepharon. This may cause fornix shallowing and long-term discomfort.

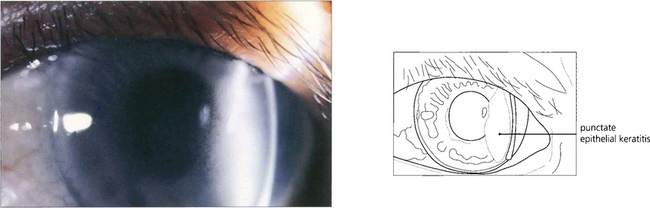

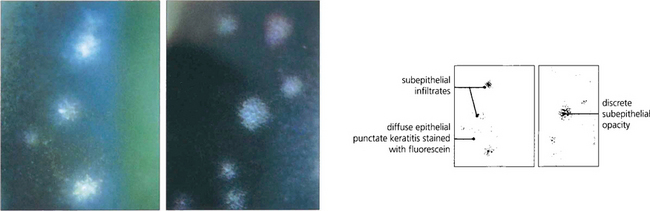

Fig. 4.6 Adenoviral keratitis is seen with the more severe forms of the disease and is particularly associated with serotypes 8, 11 and 19. It is first visible as a fine punctate epithelial keratitis that appears during the first week of the disease.

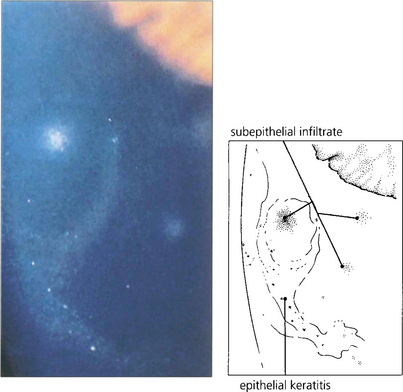

Fig. 4.7 In most cases the superficial keratitis resolves spontaneously but in more severe cases the epithelial lesions gradually coalesce towards the end of the first week to form coarse spots that subsequently become associated with the appearance of subepithelial infiltrates towards the end of the second week (left). The epithelial lesions gradually resolve and as the inflammation disappears the edges of the subepithelial infiltrate harden to produce discrete circular opacities (right).

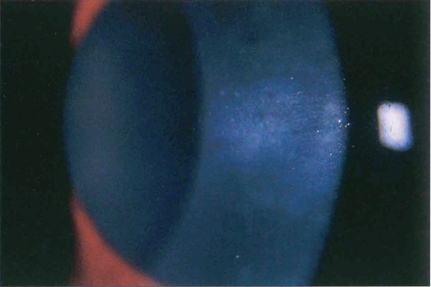

Fig. 4.8 The small circular subepithelial opacities, which are typically placed centrally in adenovirus infections, may persist for many weeks, months or, rarely, years. This patient was photographed 2 years after the initial infection. Although the use of topical steroid preparations results in the temporary disappearance of the corneal lesions, the value of such treatment is limited by the tendency for the opacities to recur following withdrawal of steroids and the potential problems of long-term steroid treatment.

HERPES SIMPLEX

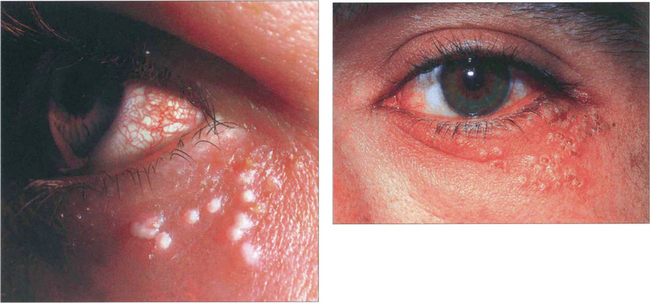

Fig. 4.10 Primary herpetic blepharoconjunctivitis begins as a vesicular eruption with surrounding erythema on the skin of the eyelids. After a few days the lesions become pustular, then crust and ulcerate. Healing takes place during the second and third week. A follicular conjunctivitis is also usually found.

Fig. 4.11 Ulceration of the mucocutaneous junction of the lid margin is common. In recurrent blepharoconjunctivitis due to herpes simplex lid margin ulcers, which will stain with fluorescein, may occur with conjunctivitis in the absence of skin lesions and may be the only evidence of specific herpes simplex infection.

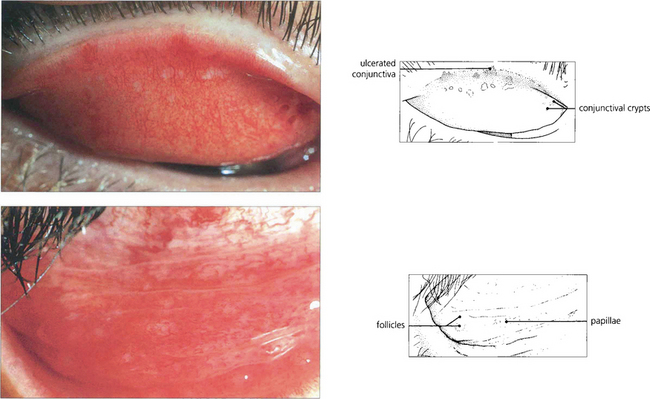

Fig. 4.12 Conjunctivitis is often present with the primary disease when it is invariably associated with a tender, enlarged, pre-auricular lymph node. It is frequently accompanied by purulent discharge and the lower fornix and tarsus show a mixed papillary and follicular reaction indistinguishable from other types of viral conjunctivitis. The upper tarsus shows small areas of conjunctival ulceration near the lid margin that are easily overlooked in the presence of marked hyperaemia. The conjunctivitis responds to treatment with a topical antiviral agent.

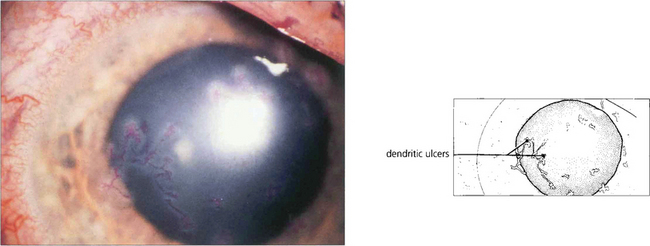

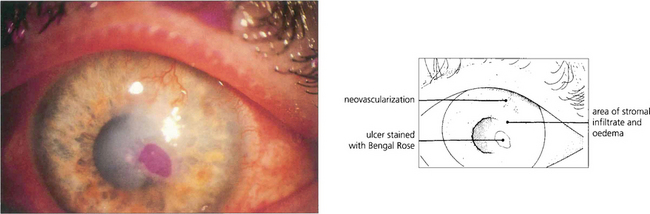

Fig. 4.13 Herpes simplex keratitis is usually unilateral. Small single or multiple dendritic ulcers are seen only rarely in the primary disease where, if keratitis is present, it is more commonly a punctate epithelial keratitis. In this example multiple small dendrites stained with Bengal Rose are present over a large area of the corneal surface. Following a primary infection of the eye, herpes simplex virus remains latent within the trigeminal ganglion and is transmitted to the eye by the fifth nerve producing recurrent disease, sometimes in association with stress or systemic illness.

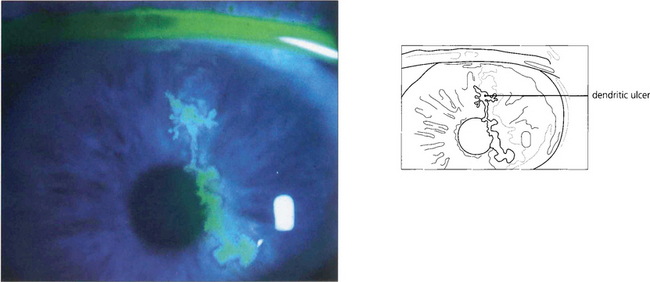

Fig. 4.14 A dendritic ulcer, the hallmark of recurrent corneal herpetic epithelial keratitis. Fluorescein stains the area of epithelial cell loss; disease is limited to the epithelium. Dendritic ulcers heal in about 7 days with a topical antiviral agent.

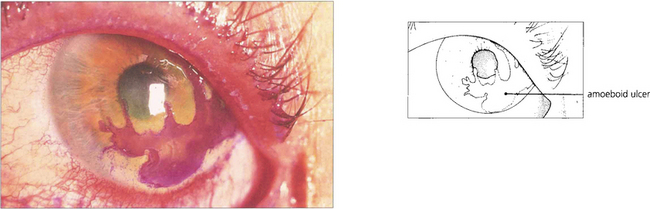

Fig. 4.15 ‘Amoeboid’ or ‘geographical’ herpetic ulceration almost invariably results from the inadvertent use of topical steroids either for keratoconjunctivitis caused by herpes simplex or for unrecognized epithelial ulceration. Persistent treatment with steroids will lead to corneal destruction and perforation.

Fig. 4.16 Chronic active stromal herpes simplex keratitis involves reactivation of viral replication in the stroma with an associated immune response. This patient has an area of ulceration surrounded by stromal oedema and infiltrate in an old herpetic scar. KP may be seen on the corneal endothelium in the involved area. There is superficial corneal vascularization. Topical steroids with antiviral cover are indicated to suppress the inflammatory reaction and minimize subsequent scarring.

Fig. 4.17 Disciform keratitis can arise with or without a history of previous corneal ulceration and presents as an area of stromal oedema associated with uveitis. These photographs shows an area of diffuse corneal stromal opacification with multiple underlying keratic precipitates centrally, indicating an active keratitis. Treatment with a combination of topical steroid and antiviral will suppress inflammation and subsequent vascularization. However, this treatment may have to be continued for many months to prevent rebound inflammation. Residual stromal scarring is usual. Patients with frequent recurrences of disease benefit from long-term oral antiviral treatment, which reduces the number and severity of relapses.

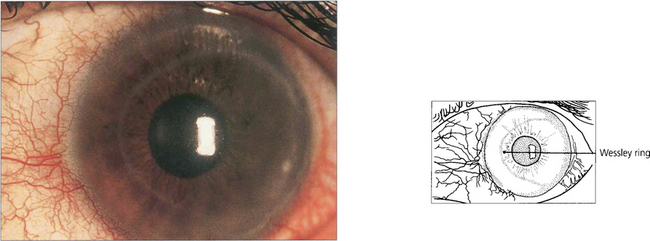

Fig. 4.18 A Wessley ring is another example of an immunological phenomenon occurring in the corneal stroma associated with herpes simplex keratitis. This is formed when soluble antigen diffuses away from the site of infection through the corneal stroma to form a precipitation line where it is neutralized by antibody.

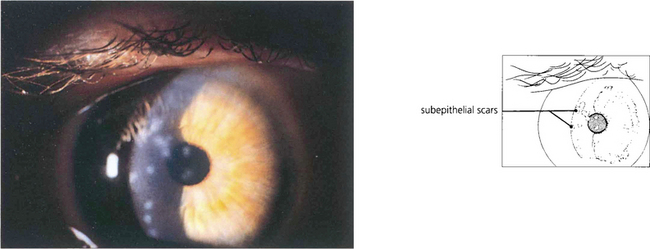

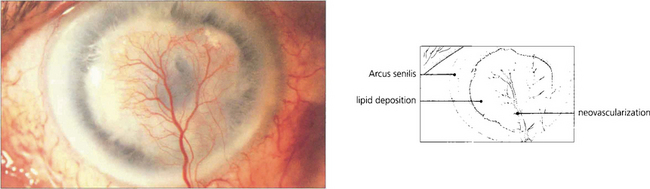

Fig. 4.19 This figure shows an end-stage chronic herpes simplex keratitis with vascularization and lipid deposition in an old stromal scar. Lipid keratopathy may also be seen in any condition that has resulted in the presence of a vascularized scar. A well pronounced arcus senilis is also present.

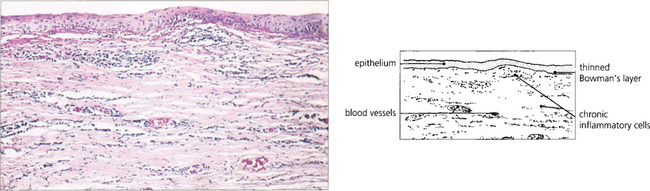

Fig. 4.20 The histological features of herpes simplex stromal keratitis show an intact corneal epithelium with destruction of parts of Bowman’s layer beneath which there are collections of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Vascularization of the corneal stroma is also evident with loss of the normal pattern of corneal lamellae.

HERPES ZOSTER

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus results from the activation of latent varicella zoster virus in the trigeminal ganglion with neuronal spread of virus through the first (ophthalmic) division of the nerve. The resulting vesicular eruption follows the distribution of the affected dermatome and may be preceded by a few days of neuralgic pain in the same area. A wide spectrum of ocular involvement may occur, including conjunctivitis, keratitis, corneal anaesthesia, iritis (see Ch. 10), secondary glaucoma or optic neuritis. Possible mechanisms of tissue damage include direct viral invasion, vasculitis and neuritis. Isolated ocular motor nerve palsies may also occur as a result of contiguous viral spread within the cavernous sinus. Systemic treatment with an antiviral drug early in the course of the disease shortens the duration and extent of the rash and reduces long-term ocular complications and postherpetic neuralgia, which can be disabling in some patients. Herpes zoster infections usually occur in otherwise healthy people but may be precipitated by debility or immunosuppression from other disease; they are also associated with HIV infection and acute retinal necrosis (see Ch. 10).

Fig. 4.21 This is an example of a zoster rash in the early stages with erythema, oedema of the lower lid, and vesicle and pustule formation following the distribution of the second (maxillary) division of the trigeminal nerve. Ocular involvement is much less common in this instance.

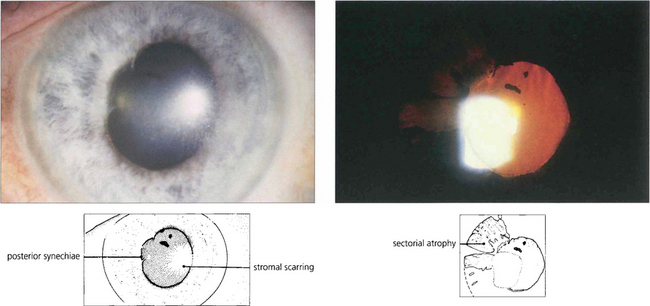

Fig. 4.22 Involvement of the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve is often associated with ocular complications from herpes zoster. This patient illustrates the healing phase of the rash during the second week when crusts have started to form and the erythema is subsiding.

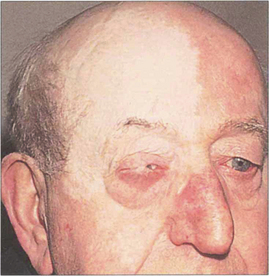

Fig. 4.23 The late stigmata of zoster infection include marked dermal atrophy leading to thinning and depigmentation of the skin, sometimes associated with more extensive tissue destruction from arteritis and inflammation. This patient has a lateral tarsorrhaphy to protect the right cornea. Such cutaneous damage has become rare with the introduction of antiviral treatment.

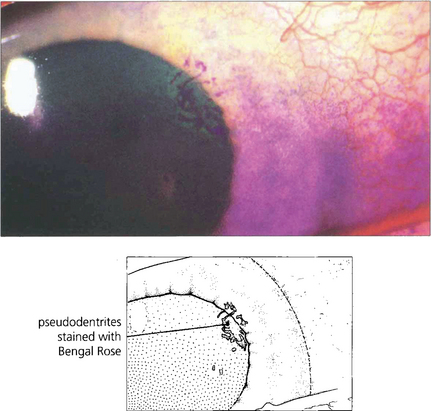

Fig. 4.24 Conjunctivitis and keratitis are features of ocular involvement during the early stages of the disease. Corneal ‘pseudo-dendrites’ from mucus deposition may form but these can be distinguished from the dendrites of herpes simplex infection by their elevated appearance, peripheral location, poor staining with fluorescein compared with Bengal Rose and their ability to be wiped easily from the corneal surface.

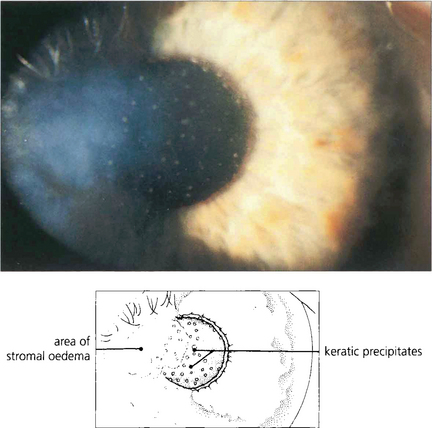

Fig. 4.25 Disciform keratitis is a common feature of corneal disease in herpes zoster. It usually appears about 2 weeks after onset of the rash, with blurring and photophobia. There is stromal oedema with KP on the endothelium and often a concurrent iritis. The cornea has reduced sensitivity. The changes are identical to those of herpes simplex stromal keratitis.

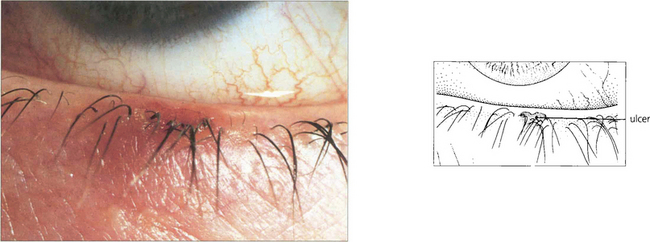

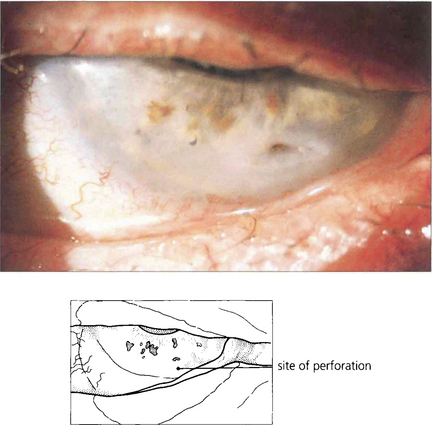

Fig. 4.26 Corneal anaesthesia or hypoaesthesia is a frequent complication of herpes zoster ophthalmicus. When this is combined with defective lid function (see Fig. 4.23), exposure may result in drying with ulceration of the corneal epithelium. In this example a small perforation has appeared in the base of an ulcer in the inferior cornea.

Fig. 4.27 Approximately 50 per cent of patients with ocular involvement develop iritis and this is frequently accompanied by vasculitis of the iris. Secondary glaucoma is common. The uveitis starts during the third or fourth week of the illness and usually requires treatment with topical steroids for many months. Sector iris atrophy from vasculitis of the radial iris arterioles is characteristic in such patients. Examination of the pupil on direct illumination may show loss of the pigmented border in a sector that reacts poorly to light, producing a characteristic spiralling of the pupil on constriction to light (see Ch. 10). The loss of the iris pigment epithelium can be seen more dramatically on retroillumination.

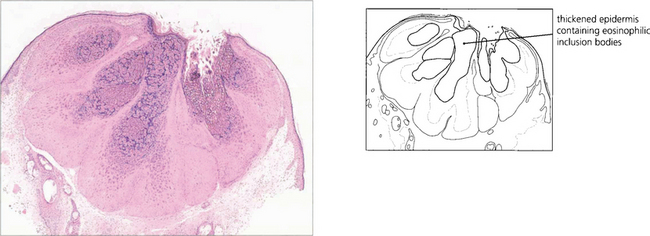

MOLLUSCUM CONTAGIOSUM

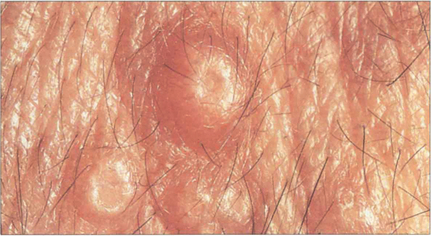

Fig. 4.28 Molluscum contagiosum produces characteristic raised skin lesions with umbilicated centres. The lesions may be either single or, as in this case, multiple.

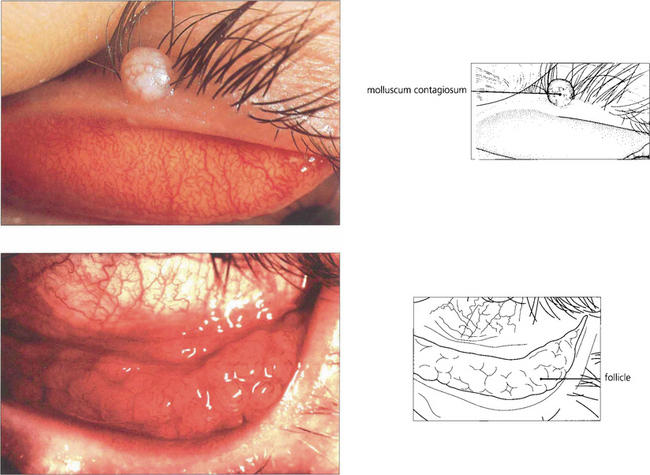

Fig. 4.29 If a molluscum lesion occurs on the lid margin virus particles may be shed into the lower conjunctival sac where they may produce a secondary follicular conjunctivitis. This is thought to be due to an immune reaction without direct conjunctival invasion by the organisms. The conjunctivitis thus produced is readily cured by removing the offending lid lesion.

CHLAMYDIAL INFECTIONS

Fig. 4.31 The conjunctival fornices show a pronounced follicular reaction associated with hyperaemia and some infiltration of the surrounding conjunctiva. Follicles in the upper fornix (left) can be inspected only by double everting the upper lid. In the lower fornix (right) individual large follicles have begun to coalesce to produce ridges of lymphoid material.

INCLUSION BODY CONJUNCTIVITIS

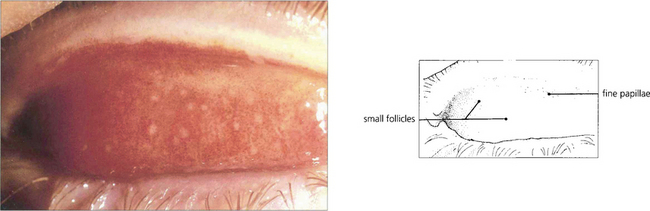

Fig. 4.32 The follicular response later spreads on to the tarsal conjunctiva, where the follicles tend to be smaller and are associated with other inflammatory signs including a papillary reaction.

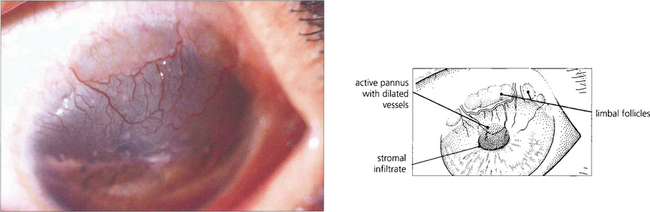

Fig. 4.33 Superficial keratitis may develop in the form of small greyish-white epithelial and subepithelial infiltrates 2–3 weeks after the onset of conjunctivitis. These infiltrates may be distinguished from those seen in adenovirus by their tendency towards a peripheral corneal distribution and their association with early pannus formation. They may persist for several months.

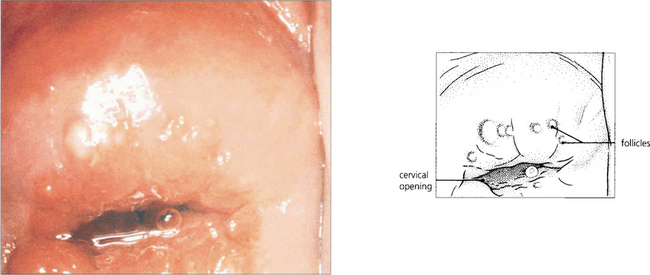

Fig. 4.34 Inclusion body conjunctivitis is transmitted sexually or during birth and is associated with cervicitis in women and urethritis in men; proctitis may also be present and consequently systemic treatment is usually indicated. This woman has well developed follicles on the cervix, characteristic of chlamydial infection. As Chlamydiae are associated with pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility all patients should be screened for evidence of chlamydial genital infection and other coincidental sexually transmitted diseases.

Fig. 4.35 In the newborn infant infection may be acquired in the birth canal during delivery and Chlamydiae are an important cause of ophthalmia neonatorum. The incubation period is usually 5–14 days but varies from 1 to 40 days. The clinical appearance of the inflamed conjunctiva differs from the adult form of the disease as the infant’s immature immune system does not allow follicle formation. The palpebral conjunctiva are hyperaemic and oedematous with a papillary reaction and are readily everted by gentle pressure on the lids from the examiner’s fingers. In this example mucopurulent exudate is present. It is important to visualize the cornea to exclude ulceration although this is more common with bacterial infections. Babies may develop systemic infection and should be treated with systemic antibiotics.

TRACHOMA

The classical description of trachoma has four stages of disease progression: stage 1, small follicles on the conjunctiva; stage 2, mature follicles with diffuse infiltration and papillary hypertrophy; stage 3, conjunctival scarring and active inflammation; stage 4, inactive infection and scar tissue. Although these broad categories of disease may be recognized in a population with hyperendemic trachoma, the classification is of limited value in determining the prognosis in an individual patient as it takes no account of the cyclical changes brought about by reinfection, the severity of the disease or the degree of visual damage. The World Health Organization has introduced a simplified classification for primary eye care, which can be performed with a hand torch and loupe in the field and can be expanded by grading the severity. This consists of trachoma follicles (TF; five or more follicles on the central upper tarsus), trachomatous inflammation (TI; diffuse inflammation of the upper tarsal conjunctiva that obscures more than 50 per cent of the normal tarsal vessels), trachomatous scarring (TS), trichiasis or entropion (TT; deviated lashes touching the cornea) and corneal opacity (CO).

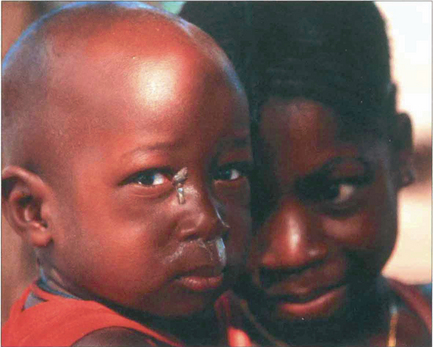

Fig. 4.36 Children are the major reservoir of disease, and eye-to-eye contact via flies is a major factor in disease transmission.

By courtesy of Mrs D Mabey.

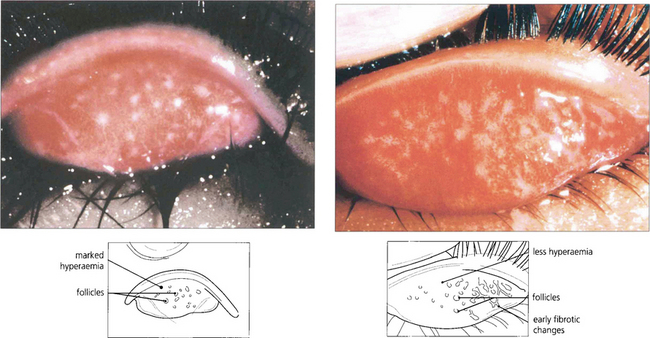

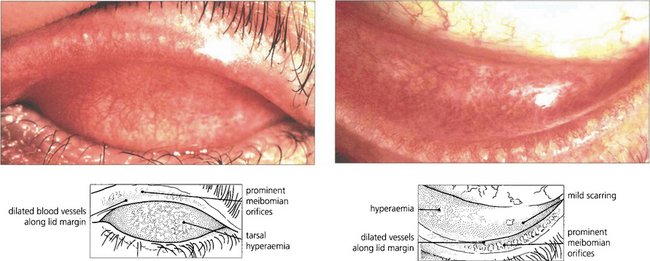

Fig. 4.37 Early trachoma with follicles and diffuse inflammatory changes on the tarsal plate and no scarring (left), resolving follicles, mild inflammatory changes and early scarring (right).

By courtesy of Mrs D Mabey.

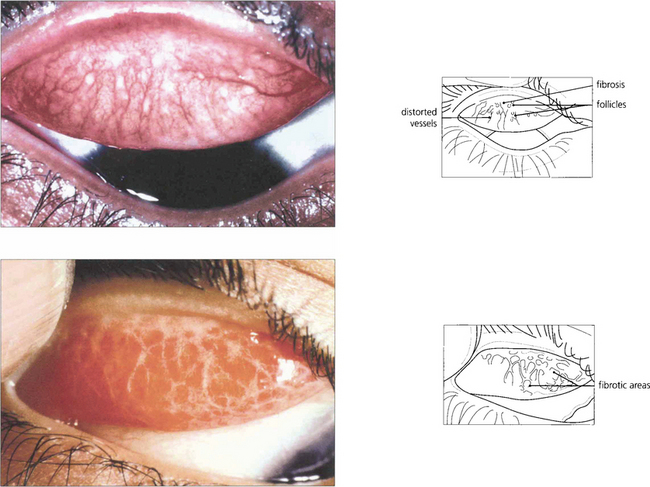

Fig. 4.38 Resolving follicles, papillary changes and scarring (top). Extensive scarring with residual inflammation (bottom). Dense scar tissue near the upper lid margin may contract leading to lid shortening and trichiasis (see also Figs 3.18 and 3.19).

By courtesy of Mrs D Mabey.

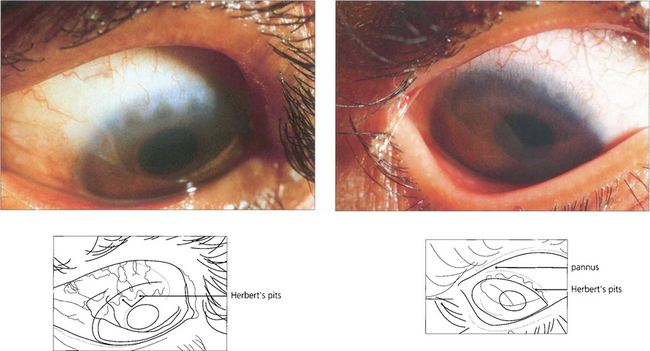

Fig. 4.40 Severe corneal scarring with inactive pannus (superficial downgrowth of vessels and scarring without infiltration) (left). Shallow depressions, known as Herbert’s pits, can be seen in another eye (right). These represent the site of earlier limbal follicles that have involuted leaving residual corneal stromal thinning.

By courtesy of Mr M G Falcon.

Fig. 4.41 The complications of severe trachoma result from the contraction of conjunctival deep scar tissue leading to cicatricial entropion, trichiasis and lid shortening (which may in turn lead to further corneal damage) in association with dry eye, also as a result of conjunctival disease. This leads to corneal scarring, vascularization and epithelialization exacerbated by secondary bacterial infection and mechanical trauma from the lid changes.

By courtesy of Mr M G Falcon.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Bacterial infections of the external eye usually respond rapidly to treatment with antibiotics, although under certain circumstances serious complications may follow. Superficial infections of the lids and conjunctiva may be treated with topical broad-spectrum antibiotic preparations, whereas deeper infections such as dacryocystitis and orbital cellulitis require systemic treatment. The most serious bacterial infections are those involving the cornea; these require urgent investigation and intensive treatment if loss of vision through corneal perforation, scarring or endophthalmitis is to be avoided (see Ch. 6).

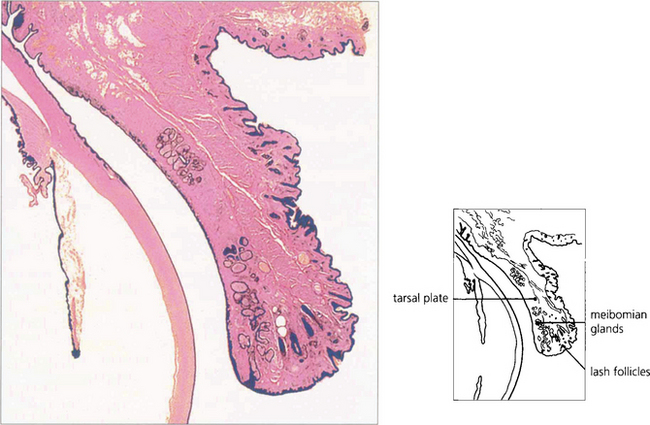

Fig. 4.42 Acute bacterial infections of the eyelid usually take the form of a stye in which a lash follicle becomes infected or acute chalazion in which one of the meibomian glands of the eyelid is involved.

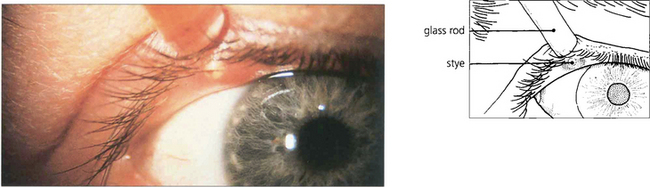

Fig. 4.43 A stye is a small localized abscess visible on the lid margin around the root of an eyelash. Resolution occurs spontaneously following removal of the eyelash and no further treatment is indicated.

Fig. 4.44 Acute chalazion is an infection of a meibomian gland in which localized abscess formation takes place within the tarsal plate. The infection may be treated with heat and antibiotic ointments, but resolution tends to be slow and a painless swelling may persist for several weeks or months owing to the formation of a granuloma (chalazion, meibomian cyst). At this stage surgical incision and curettage can be performed to remove the lesion (see Ch. 2).

CHRONIC BLEPHARITIS

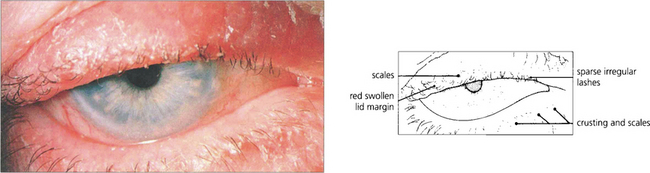

Fig. 4.45 Anterior blepharitis is characterized by the presence of crusts and scales on the lid margins which may be erythematous and slightly swollen, and chronic staphylococcal infection. The eyelashes are irregular and fewer in number than normal. Conjunctival inflammation is unusual. Most cases respond to simple lid margin cleansing and antibiotic ointment applied to the lid margins.

Fig. 4.46 Posterior blepharitis is characterized by meibomian gland dysfunction. The lid margin is red and thickened and the meibomian gland orifices are filled with an oily or thickened secretion that can be expressed by pressing on the lid margin. Signs of chronic conjunctival inflammation are usually present. The condition may be associated with changes in meibomian lipids resulting in stagnation and occlusion of the gland openings. An increased staphylococcal population may generate local hypersensitivity reactions which may be particularly symptomatic in some individuals. Lid toilet with bicarbonate solution or water with baby shampoo helps to remove oily secretions from the lid and lashes. More severe cases can be treated with long-term systemic low-dose tetracycline and, where necessary, dilute topical steroid may be used with caution to control the hypersensitivity reaction.

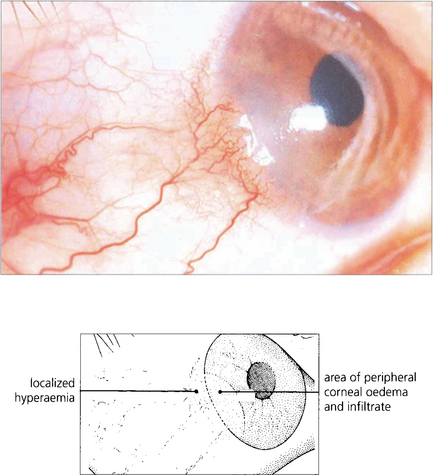

Fig. 4.47 Marginal keratitis appears in association with chronic blepharitis when discrete yellowish-white infiltrates appear in the periphery of the cornea, usually singularly but occasionally with involvement in more than one quadrant. Localized injection of the conjunctiva is visible adjacent to the area of keratitis. The condition is the result of a localized staphylococcal hypersensitivity reaction (although identical changes can occasionally be seen with herpes simplex virus) and responds well to topical steroid drops.

ROSACEA

Fig. 4.48 Excessive meibomian secretion may also be a feature of acne rosacea. This photograph shows the characteristic facial appearance of the condition (left) together with the rhinophyma associated with sebaceous hypertrophy (right). Note the superficial dilated blood vessels.

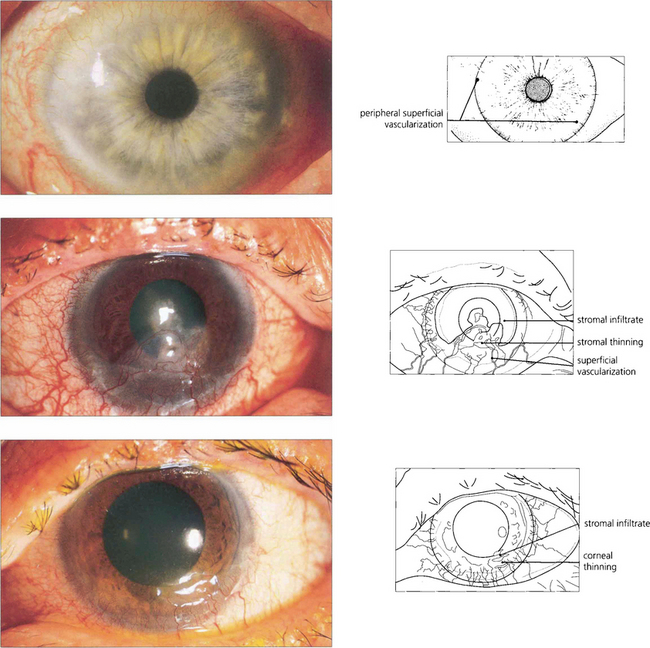

Fig. 4.49 A mild case of acne rosacea-associated keratoconjunctivitis shows fine superficial neovascularization of the limbus extending on to the cornea (top). In a more severe case there is blepharoconjunctivitis, marked corneal vascularization and scarring (middle). With active disease the vessels are dilated and there is often a cellular infiltrate at their tips. Vascularization may be associated with thinning and, rarely, perforation of the peripheral cornea (bottom).

BACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

Fig. 4.50 Bacterial conjunctivitis is characterized by its acute onset, profuse thick purulent discharge and rapid response to topical antibiotic therapy. Diagnosis depends on the demonstration of causative organisms by standard bacteriological techniques. Important causes include Staphylococcus, Pneumococcus, Moraxella and Haemophilus bacteria.

Fig. 4.51 Ophthalmia neonatorum can be due to Chlamydiae (see Fig. 4.35), but is more commonly a result of bacterial infection acquired during birth or from cross-infection in the neonatal period. Staphylococcal infections are the most common cause although gonococcal infection used to be a severe problem producing a florid purulent conjunctivitis that led to blindness from corneal involvement. In preantibiotic days, babies were treated prophylactically with silver nitrate drops postdelivery to prevent this complication. It is essential to visualize the cornea in any baby with conjunctivitis to exclude corneal ulceration.

LEPROSY

Fig. 4.52 The zygomatic branch of the seventh nerve is often selectively involved because it is relatively superficial, cooler and therefore predisposed to bacterial invasion. Partial seventh nerve palsies are common, leading to gross corneal exposure.

By courtesy of Mr T J ffytche.

Fig. 4.53 The anterior chamber has a lower temperature than body temperature and the anterior segment is vulnerable to direct invasion by bacilli. Corneal anaesthesia results from involvement of the corneal nerves and is exacerbated by the problems of exposure. A low-grade chronic iritis is common; it destroys iris tissue and may cause cataract. Sympathetic nerves are selectively affected in the iris as they are small and nonmyelinated and this produces characteristic severe chronic miosis that enhances the effects of lens opacities.

By courtesy of Mr T J ffytche.

ANTHRAX

Fig. 4.55 Cutaneous lesions are characteristic. This Libyan woman has the typical coal-black eschar of resolving anthrax infection on the right upper lid. The disease starts as a pimple with oedema and no pus surrounded by purplish vesicles. The eschar forms rapidly in a few days and eventually sloughs, with scarring of the lid and corneal exposure.

By courtesy of Mr J Winstanley.

PARASITIC DISEASE AND INFESTATIONS

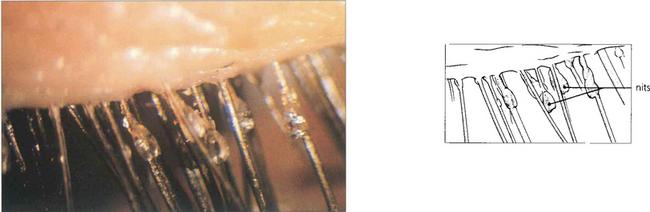

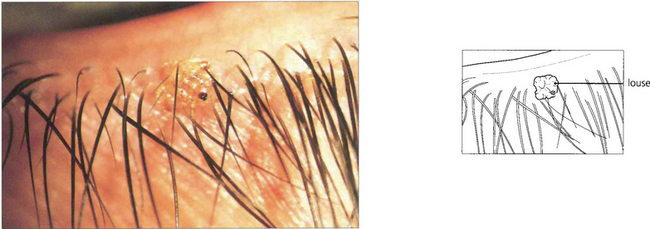

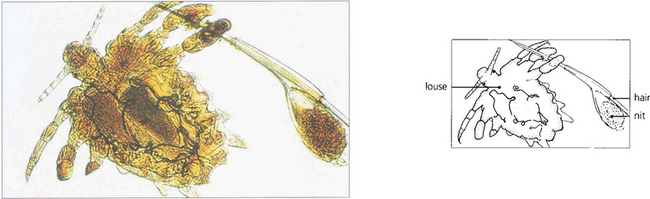

PEDICULOSIS

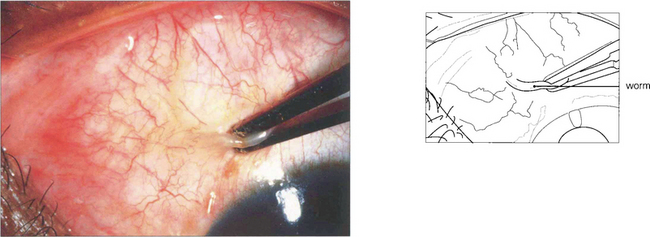

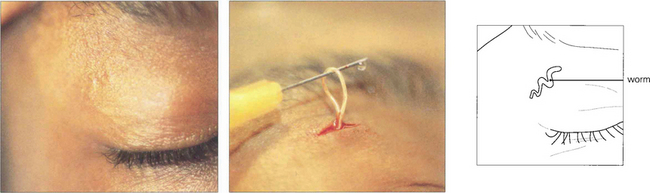

LOA LOA

ONCHOCERCIASIS (RIVER BLINDNESS)

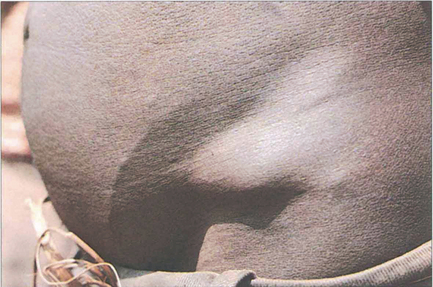

Fig. 4.61 The presence of dead microfilaria produces an intensively itchy rash, particularly on the lower body. There is hyperpigmentation and atrophy of the skin which heals badly. Trophic ulcers may develop.

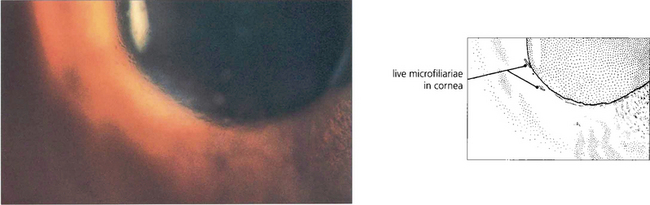

Fig. 4.62 Adult worms form nodules throughout the body, but particularly subcutaneously over bony prominences. If the nodules are on the head they are particularly dangerous, as the microfilaria easily spread to the eye. Nodules can be excised surgically.

Fig. 4.63 Microfilaria can be seen in the cornea, aqueous and vitreous as mobile, small, slender structures about 0.3 mm in length. They enter the eye from the surrounding subcutaneous tissue which is why it is particularly important to remove adult worm nodules from the head.

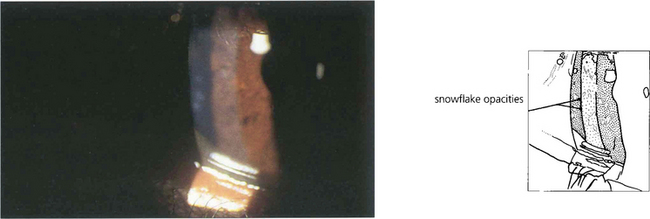

Fig. 4.64 Dead microfilaria produce fluffy ‘snowflake’ opacities in the anterior corneal stroma.

By courtesy of Mr I Murdoch.

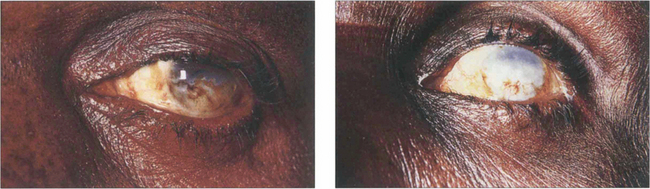

Fig. 4.65 More advanced cases show a blinding sclerosing keratitis with pigmentary migration on to the cornea.

By courtesy of Mr I Murdoch.

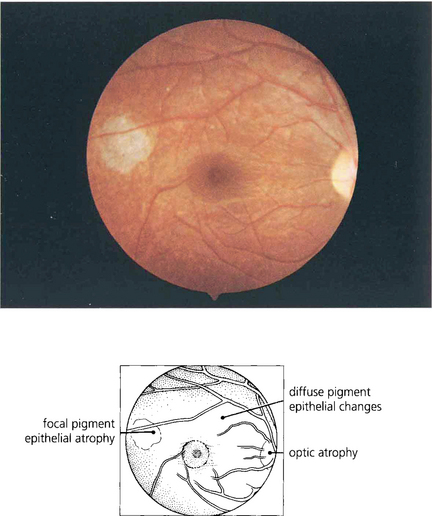

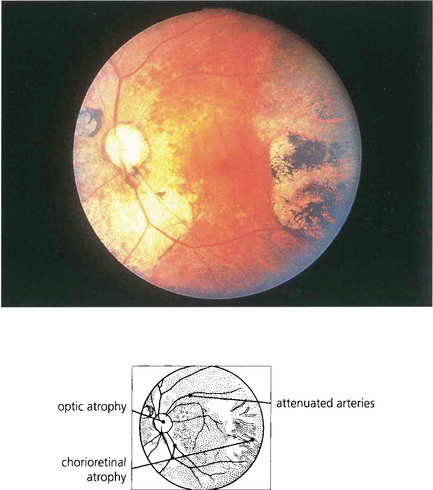

Fig. 4.66 Chorioretinal atrophy and optic neuritis are produced by a low-grade chorioretinitis. The early changes are seen temporal to the macula as atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. They probably arise from invasion of the choroid along the posterior ciliary arteries by microfilaria which are frequently produced in nodules on the temples.

By courtesy of Professor A Bird.

Fig. 4.67 More advanced changes are seen in this eye. The macula is often spared until late in the disease. Optic nerve disease and visual field loss may occur in the absence of retinal disease. Diethylcarbamazine (DEC) destroys the microfilaria but may precipitate further visual loss from the reaction to dead microfilaria in the optic nerve and retina.

By courtesy of Mr I Murdoch.