Infections of the nervous system I

The central nervous system is protected by the blood–brain barrier and neurological infections are relatively rare in the western world. There are, however, many different infections that can occur. In this section, the more common infections are discussed. Other infections, such as leprosy and HTLV-1 myelopathy, are dealt with elsewhere.

Meningitis

Bacterial meningitis

Overcrowding and poverty have been shown to be risk factors.

The clinical features of meningitis are:

There may also be altered consciousness, seizures and focal signs in about 15% of patients. Patients may have a positive Kernig’s sign (Fig. 1), another sign of meningism. Meningococcal meningitis may be associated with a purpuric rash (Fig. 2).

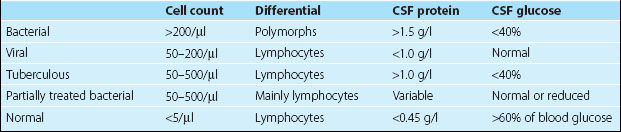

Blood cultures should be taken immediately. Lumbar puncture is important to confirm the diagnosis and determine the organism. However, if the patient has focal signs, altered consciousness or has had a seizure, then a CT brain scan or MRI needs to be done prior to the lumbar puncture. In severely ill children, lumbar puncture may lead to deterioration and should be avoided. The CSF findings are indicated in Table 1. The Gram stain and culture are usually diagnostic, and can be helped by newer tests for specific bacterial antigens.

The main differential diagnoses are subarachnoid haemorrhage and other meningitic illnesses.

Tuberculous meningitis

This is a more insidious onset meningitis. There is usually a general malaise associated with a progressive headache, which may be followed by development of multiple lower cranial nerve palsies and radiculopathies. The diagnosis may prove to be difficult. Investigations may find abnormalities such as an elevated viscosity, though this is variable. The CSF findings reflect the more chronic process with a lower level of lymphocyte pleocytosis, raised protein and low glucose. The differential diagnosis is wide and includes other infections such as fungal infections, brucella or spirochaetal disease and non-infectious diseases such as sarcoid and malignant meningitis, particularly lymphoma. Diagnosis can be difficult as culture of Mycobacterium tuberculosis takes 6 weeks. Newer techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are proving to be helpful. Treatment is often initiated on a suspected diagnosis having ruled out alternatives as far as possible. Triple therapy with isoniazid, ethambutol and rifampicin, plus pyrazinamide, which crosses the blood–brain barrier well, is used. Treatment is for 9 months.

Encephalitis

Infectious encephalopathies, either alone or with an associated meningitis (meningoencephalitis) present with altered behaviour, seizures, confusion or coma (p. 50). These patients often have a history of a prodromal infection and are febrile. Their CSF shows some abnormalities: a slightly lymphocytic pleocytosis (50–150 cells/µl) and an elevated protein level, usually with a normal glucose level. Brain imaging is usually normal. The EEG is slow, and cannot distinguish between infective and other encephalopathies.

Cerebral abscess

Cerebral abscesses are now rare. They result from:

direct spread into the brain from adjacent tissues (75%), such as paranasal sinus infection, or middle ear and mastoid infection

direct spread into the brain from adjacent tissues (75%), such as paranasal sinus infection, or middle ear and mastoid infectionThe presentation is with progressive headache (75%), focal neurological symptoms or signs (50%), fever (50%) and seizures (30%). The brain scan shows one or more usually ring enhancing lesions with associated oedema. There may be features of the primary infection, ear or sinus, and markers of systemic infection. The main differential diagnosis is cerebral tumours (p. 94). Management is with a combination of antibiotics and surgical drainage. There is a high incidence of epilepsy following cerebral abscess.

Slow infections

The spongiform encephalopathies, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) and new-variant CJD, are rare but have been intensively studied recently. CJD occurs in about 1 per million per year; new-variant CJD had about 100 cases reported by 2004. They are caused by abnormalities in prion proteins. Some cases of CJD occur from transmission from using infected dural transplants or human pituitary extracted growth hormone. Most CJD is sporadic, but 5% of cases are familial and due to mutation of endogenous prion protein (chromsome 20), referred to as the Gerstmann–Straussler syndrome. The onset of the sporadic disease is usually between 50 and 70 years of age with dementia and subsequently myoclonus and typical EEG changes (Fig. 3); median survival is less than 1 year.