Chapter 33 Infections of the genital tract

VULVOVAGINAL INFECTIONS

Genital herpes

The first clinical attack of genital herpes is usually worse than the recurrences. It follows sexual contact with an infected person who was either symptomatically or asymptomatically shedding the virus. The inner surfaces of the labia majora are most likely to be infected. After a short period of itching or burning, small crops of painful, reddish lumps appear which become blisters within 24 hours. The blisters ulcerate rapidly to form multiple shallow, painful ulcers (Fig. 33.1). The surrounding tissues become oedematous and secondary bacterial infection may occur, aggravating the oedema and pain. Micturition may be very painful. Over 5 days the ulcers crust over and heal slowly, the healing being complete in 7–12 days after the appearance of the blisters for a primary infection, and less for recurrences. During this time, and intermittently, the virus is shed from the infected area and in vaginal secretions. The virus also enters the sensory nerves supplying the affected area, and tracks to lie in the dorsal root ganglion. It may lie dormant for the rest of the person’s life, or may be reactivated and track back along the nerves to cause a new attack of herpes. Second and subsequent attacks are less severe, but can cause considerable discomfort and affect relationships.

Diagnosis

To make a definitive diagnosis of genital herpes, the blisters should be pricked to obtain vesicular fluid and the ulcers rubbed with a cotton tipped-bud to obtain virus-infected cells, and the swab sent in a virus transport medium for culture. Alternatively (particularly for older lesions) testing by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is more sensitive. A full STI screen should be completed (Box 33.1).

Genital warts (condylomata acuminata)

Genital warts are caused by types 6 and 11 of the human papilloma virus (HPV), usually transmitted sexually. Vulval infections are the most common, although the virus may spread to infect the vagina, the perineum (Fig. 33.2) and occasionally the cervix.

The importance of HPV infections is that they are surrogates for the exposure to and carriage of the oncogenic HPV types 16 and 18, which are the cause of cervical carcinoma. The risk of this occurring from vulval warts is small. This is discussed further in Chapter 37.

Syphilitic vulval ulcer

Syphilis is caused by invasion of the tissues by Treponema pallidum and is sexually transmitted. The primary lesion, which is often unrecognized, is a small papule that appears at the site of inoculation, usually 14–28 days after the person is infected. In women, the usual site of infection is one of the labia majora, but the cervix may be infected instead. The papule rapidly enlarges to form an oval lesion of variable size, the centre of which becomes eroded and granulomatous. The edges of the eroded area are sharp, and outside this a thickened, indurated zone occurs, hence the name for the lesion – hard chancre. The chancre is painless and may be ignored by the woman or considered a small sore of no consequence, but as it is teeming with treponemas it is highly infectious. The primary lesion disappears in 21 days or so. Secondary lesions, which include mucous patches and condylomata lata (Fig. 33.3), appear 5–6 weeks later.

Vaginal discharges and infections

The vagina harbours large numbers of bacteria, which constitute its normal flora (Table 33.1). However, a significant number of women harbour potential pathogens such as E. coli, anaerobes, Candida spp., and Gardnerella vaginalis (bacterial vaginosis). They produce symptoms in only a few women.

| Organism | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Lactobacilli | 80–90 |

| Staphylococci, micrococci | 50–70 |

| Ureaplasma | 40–50 |

| Anaerobes | 20–50 |

| Streptococci | 20–30 |

| Gardnerella | 10–30 |

| E. coli | 5–15 |

| Candida spp. | 5–15 |

| Bacteroides | 5–10 |

| Trichomonas | 3–7 |

Pathological vaginal discharges

The three common irritating pathological vulvovaginal discharges are caused by:

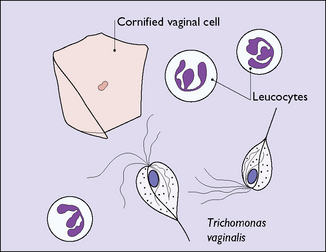

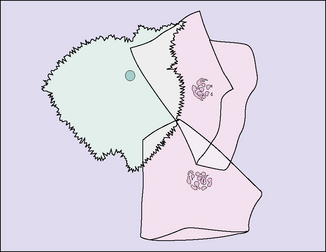

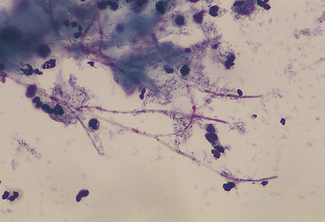

In many cases they can be differentiated in the doctor’s office or outpatient clinic by taking a sample of the discharge and looking at a ‘wet preparation’ under a microscope. Part of the swab is mixed with a drop of saline and part is mixed on a second slide with two drops of 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH). The saline preparation may reveal trichomonal flagellates, which can be observed moving and thrashing their tails (Fig. 33.4). Alternatively, the wet preparation may also show vaginal epithelial cells with indistinct borders, ‘clue cells’ due to the ‘hundreds and thousands’ effect of the presence of large numbers of Gram-variable coccobacilli (Fig. 33.5), which suggest that the woman has bacterial vaginosis. Clue cells are more readily apparent on a Gram-stained slide. Bacterial vaginosis is also suggested by a strong fishy smell from the KOH preparation (the amine test). The KOH preparation is examined under a microscope, when hyphae of Candida species can be seen, if this is the cause of the discharge (Fig. 33.6).

Trichomoniasis

The parasite Trichomonas vaginalis is a 20 mm long flagellate. It is a little larger than a leukocyte (see Fig. 33.4). Once introduced into the vagina, it shelters at the bottom of the crypts of the velvet-like vaginal epithelium. It may be symptomless, or may cause vaginitis with discomfort and discharge. It is readily sexually transmitted and infects the man’s urethra, where it is often symptomless.

Candidiasis (thrush)

Candida spp. infect the vaginal epithelial cells, particularly if in the fungal-germinating stage, when they develop spores and long threads (hyphae) (see Fig. 33.6). Inside the cells they may lie dormant until environmental conditions encourage germination. Candida spp. may also infect the vulval skin, the anogenital region, the mouth and the intestinal tract. For recurrent candidiasis underlying conditions such as diabetes, the recent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics or immunosuppressive therapy, e.g. corticosteroids, and HIV should be considered.

INFECTIONS OF THE INTERNAL GENITAL ORGANS

Ascending vaginal infection is controlled to some extent by the following mechanisms:

As it may be difficult, clinically, to determine which organ is infected, and as more than one organ is usually infected, the condition is generally diagnosed as acute pelvic infection or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Infection of the internal genital organs may also occur following an abortion or after childbirth. In these cases the infective agents (which are usually staphylococci, streptococci, E. coli or anaerobes) enter the tissues through cervical lacerations, or more frequently, through the placental bed. Infections following pregnancy or childbirth are discussed in Chapter 23.

STI-related pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

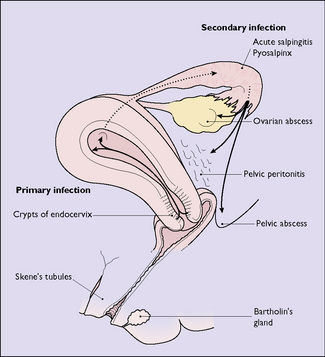

The microorganisms invade the columnar cells lining the crypts of the cervical canal. They may be eliminated by the body’s immune system, spread rapidly to cause an acute infection, or remain quiescent in the columnar cells, with the potential to spread to other pelvic organs. Spread occurs via the lymphatics, the veins or, possibly, by ‘riding on the back of spermatozoa’. In a few instances the infection is carried into the uterus during the insertion of an intra-uterine device, and it is advisable to screen women for Chlamydia and Neisseria gonorrhoeae prior to insertion (see p. 248).

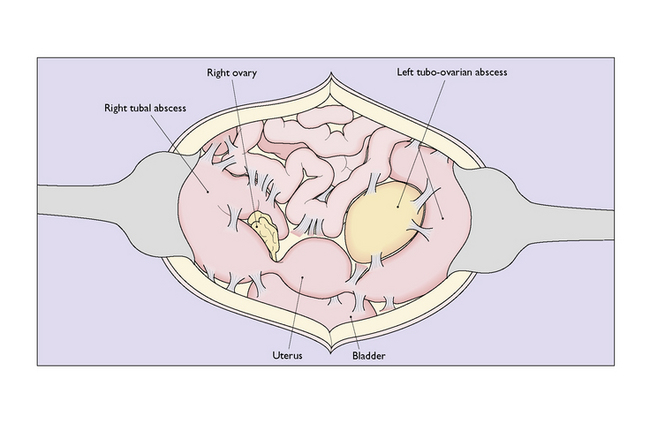

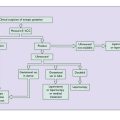

The endometrium is first infected, causing endometritis. From here the infection may spread to the myometrium, causing myometritis, or through the uterine cavity to the Fallopian tubes, causing acute or subacute salpingitis. In some cases the ovaries and the pelvic peritoneum may be involved (Fig. 33.7).

Chronic genital infection (chronic PID)

Chronic genital infection is a long-term sequela of acute or subacute infection and may follow post-abortion or puerperal infection. It may present as a pyosalpinx, a hydrosalpinx or a chronic tubo-ovarian abscess (Fig. 33.8). In other cases the infection involves the connective tissues of the pelvis, causing chronic pelvic cellulitis.

Pyosalpinx

Pyosalpinx, or ‘chronic pus tube’, forms as a result of blockage of the lumen of the oviduct at the fimbrial end and at one or more points along the Fallopian tube. This occurs in the acute phase of the infection, and exudate accumulates, distending the oviduct to a greater or lesser degree (Fig. 33.9). The distension of the oviduct flattens the endosalpinx and the wall of the oviduct is thickened by the inflammatory process. Because the inflammatory process extends through the wall of the oviduct, adhesions to surrounding structures are common. The ovary may be involved to form a chronic tubo-ovarian abscess.

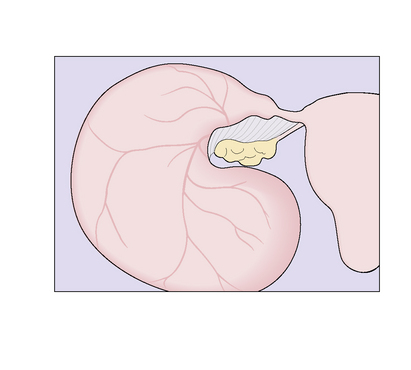

Hydrosalpinx

Hydrosalpinx (Fig. 33.10) is the end result of burnt-out pyogenic salpingitis, which was of low virulence but highly irritating, producing large quantities of clear exudate within the closed portion of the oviduct. The distended oviduct has a thin wall, which is translucent and usually retort-shaped (Fig. 33.11). Adhesions to contiguous structures may be present.

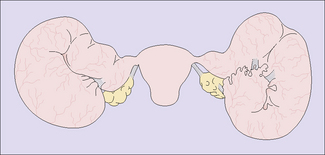

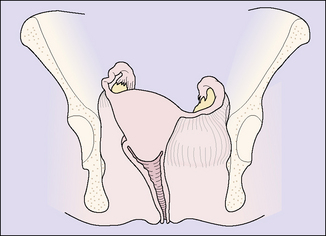

Chronic pelvic cellulitis

Chronic pelvic cellulitis is less common today but still occurs. It is usually the sequela of acute pelvic cellulitis and results in thickening and fibrosis of the connective tissues of the parametrium, with the result that the position of the uterus is distorted and it is relatively or absolutely immobilized (Fig. 33.12). The symptoms of chronic pelvic cellulitis are variable. The most common complaint is a chronic deep pelvic ache, often localized to one side, and backache. Deep dyspareunia is frequent, and may be so severe as to prevent sexual intercourse. Vaginal examination shows a tender uterus drawn to one side and relatively fixed in position.