Chapter 45 Infections of the Biliary Tract

![]() Video related to this chapter’s topics: Biliary Tract Infections–Worms

Video related to this chapter’s topics: Biliary Tract Infections–Worms

Introduction

The histologic definition of cholangitis is inflammation of the bile duct. However, when used in practice, cholangitis refers to a characteristic clinical presentation associated with bile duct obstruction and bacterial infection. Other etiologies of bile duct inflammation have a preceding descriptor (e.g., parasitic cholangitis). All types of bile duct inflammation may be complicated by obstruction and secondary bacterial infection. The conditions predisposing to cholangitis are listed in Box 45.1.

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

Contraindications

Contraindications for ERCP in biliary tract infections are similar to other endoscopic procedures. Patients who are unable to tolerate conscious sedation because of cardiopulmonary disease require an anesthesia assessment. Patients with an allergy to contrast agents or iodine are at increased risk of a contrast allergy during ERCP. Premedication with steroids and use of a nonionic or low-osmolality contrast agent are recommended to reduce this risk.1

ERCP in pregnancy is apparently safe for both the mother and the fetus, whereas a delay in definitive treatment of cholangitis may be life-threatening. Radiation exposure to the fetus is limited by shielding the uterus with a lead apron, short periods of fluoroscopy, avoiding magnification, and avoiding hard copy radiographs.2

Preparation

The patient should be given nothing per mouth (NPO) after midnight the day before ERCP. Coagulopathy should be corrected if possible. A decision to discontinue anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents should be individualized. There is insufficient evidence to support routine discontinuation of aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs before therapeutic ERCP procedures. Patients with a history of a contrast allergy are given prednisone, 20 mg by mouth, 13 hours, 7 hours, and 1 hour before the procedure.1 Conversely, the use of noniodinated contrast agents in place of premedication with steroids is favored by many clinicians. Antibiotics should be administered for prophylaxis of post-ERCP cholangitis if indicated.

Postprocedure Care

The efficacy of antibiotics after successful endoscopic therapy of cholangitis is unknown. In a retrospective analysis of 80 patients with cholangitis who underwent endoscopic therapy, there was no difference in outcome between the group receiving antibiotics for 3 days or less and the group receiving antibiotics for more than 3 days after ERCP.3 No placebo-controlled study addressing the use of antibiotics in cholangitis after endoscopic drainage has been done, and we generally do not continue antibiotics after successful endoscopic therapy.

Complications

Complications of ERCP include the complications inherent to any endoscopic procedure, including reactions to medications, cardiopulmonary complications, infection, perforation, and hemorrhage, and complications specific to ERCP, such as pancreatitis, postsphincterotomy hemorrhage, and biliary infection. Infectious complications of ERCP are post-ERCP cholangitis and long-term postsphincterotomy cholangitis. The rate of complications related to ERCP is 5% to 8%; risk of complications related to ERCP is 0.3%.4,5

Post–Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Cholangitis

The risk of cholangitis immediately after ERCP is very low—0.7% in a large series from a single referral center where drainage of obstructed ducts is practiced aggressively.6 The incidence of cholangitis increases 10-fold if diagnostic ERCP is undertaken without performing biliary drainage when an obstruction is found.7 This increased incidence is due to contaminating sterile bile with enteric bacteria, which in the presence of obstruction results in cholangitis. Any obstructed segment of the biliary tract opacified during cholangiography should be drained. Improper disinfection of duodenoscopes or use of contaminated water also increases the risk of post-ERCP cholangitis and bacteremia, especially with Pseudomonas aeruginosa.8,9

Long-Term Postsphincterotomy Cholangitis

Surgical or endoscopic sphincterotomy is a risk factor for bacterial contamination of the biliary tract,10 likely by facilitating transpapillary migration of enteric bacteria. Escherichia coli is the most common organism identified. Analysis of patients after cholecystectomy who underwent sphincterotomy revealed a predisposition for developing brown stones or sludge within the common bile duct (CBD) in association with bacteriobilia.11 However, these data may be biased by predilection in choledocholithiasis prompting sphincterotomy in the first place.

Cholangitis

Bacterial cholangitis results from bile duct obstruction or previous biliary instrumentation. Enterobacteriaceae are the most common causative organisms, and blood cultures are positive in 50% of patients.12 Isolation of enterococci or multiple organisms from bile is more common in patients with a biliary endoprosthesis13 or bilioenteric anastomosis. Charcot’s triad of right upper quadrant pain, fever, and jaundice is present in 70% of patients with acute bacterial cholangitis. The addition of hypotension and confusion constitutes Reynolds’ pentad, which is present in less than 5% of patients with cholangitis but is significantly associated with mortality.14 Right upper quadrant pain and fever may be absent in elderly patients, diabetic patients, or patients treated with systemic corticosteroids.

Anatomy

Postoperative Cholangitis

Patients who have undergone bile duct reconstruction with creation of a hepatojejunostomy are at risk of postoperative cholangitis. This condition is especially prevalent in patients with biliary atresia.15 Bacterial colonization of the hepatojejunostomy and stoma obstruction by food debris may be pathogenic factors.

Sump Syndrome

Sump syndrome occurs after creation of a choledochoduodenostomy to manage retained CBD stones in a dilated bile duct. The distal bile duct between the papilla and the anastomosis becomes a stagnant reservoir or sump into which sludge, calculi, and food can collect. The clinical presentation may include recurrent pain, cholangitis, hepatic abscess, or pancreatitis. Management with endoscopic sphincterotomy with extraction of debris from the bile duct is successful in most patients.16 In case series, recurrence of symptoms has been noted in 0 to 19% and results from stenosis of the sphincter of Oddi.17,18 A repeat sphincterotomy should be considered.18

Preparation

Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended routinely in patients with biliary obstruction undergoing ERCP for prevention of endocarditis or post-ERCP cholangitis.19,20 However, in patients with cholangitis, broad-spectrum antibiotics providing coverage of gram-negative bacilli and Enterococcus species are indicated until biliary drainage is successfully completed.

Procedure

Intraluminal Obstruction

Biliary Stricture

Outcomes

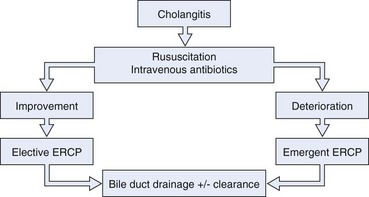

Treatment of acute cholangitis includes resuscitation, antimicrobials, and biliary tract drainage (Fig. 45.2). Management of respiratory and circulatory insufficiency in a monitored setting and administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics should precede, but not delay, definitive biliary tract decompression in a severely ill or deteriorating patient.

Fig. 45.2 Algorithm for management of cholangitis. ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Calculous Cholangitis

Biliary drainage can be accomplished endoscopically, percutaneously, or surgically. Endoscopic treatment, either sphincterotomy with stone extraction21,22 or biliary stent or nasobiliary drain insertion, is superior to surgical treatment in patients with severe cholangitis. Endoscopic sphincterotomy with stone extraction resulted in increased survival compared with surgery in a retrospective cohort of patients with acute calculous cholangitis21; this was despite a higher number of concomitant medical problems and increased age in the patients managed endoscopically. Lai and colleagues23 randomly assigned 82 patients with calculous cholangitis requiring emergent therapy to surgery or ERCP with nasobiliary catheter placement. The mortality in the surgical arm was significantly higher than in the endoscopic arm—32% and 10%. In addition, there were an increased number of nonfatal complications in the group undergoing surgery.

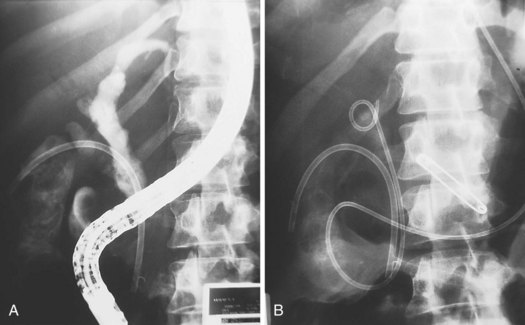

Sphincterotomy and stone extraction is usually attempted during the initial ERCP. However, in critically ill patients with acute cholangitis secondary to choledocholithiasis, it may be prudent to achieve biliary drainage endoscopically, by insertion of a stent or nasobiliary catheter, and defer stone extraction to a later time. Therapeutic response, procedure-related complications, and length of procedure are similar for biliary stents and nasobiliary catheters, but inadvertent catheter removal and patient discomfort are greater in patients who receive a nasobiliary catheter.24 Approximately 10% of patients have cholangitis owing to stones that cannot be removed by standard means, including mechanical lithotripsy. These stones include large stones, stones located proximal to a stricture, or stones greater than the diameter of the distal bile duct. Options are endoscopic EHL, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, endoscopic laser lithotripsy, and permanent biliary stent placement.25–27 Increasingly, the use of adjunctive biliary balloon sphincteroplasty is being used to remove CBD stones safely and effectively. An occlusion cholangiogram at completion of ERCP may ensure clearance but carries a significant risk of bacteremia in this situation.

If all stones or stone fragments cannot be removed during the initial endoscopic session, a stent should be left in place to provide bile drainage and prevent further cholangitis (Fig. 45.3). Long-term stent therapy is no longer advisable because of the high incidence of cholangitis and related deaths.28,29 Similar techniques can be employed in the cystic duct to treat Mirizzi’s syndrome.26,30,31 In a patient with cholangitis and gallstones but no evidence of choledocholithiasis on cholangiography, empiric endoscopic sphincterotomy does not appear to decrease the risk of subsequent episodes of cholangitis and results in a higher ERCP complication rate.32

Cholangitis Secondary to a Biliary Stricture

Biliary tract obstruction secondary to a malignant stricture rarely causes cholangitis, unless the bile has been contaminated with bacteria during a previous biliary intervention. Patients with strictures involving the biliary hilum should undergo stent placement into the right and the left hepatic ducts when technically possible because bilateral decompression would improve patient survival.33 This is especially important if the biliary tract proximal to the stricture has filled with contrast material.

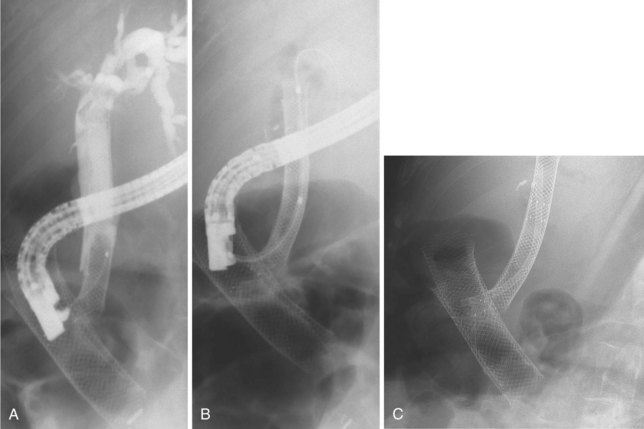

Cholangitis Secondary to Stent Occlusion

Plastic biliary stents develop a bacterial biofilm on their surface,34 which leads to stent occlusion and risk of cholangitis. Uncovered self-expandable metal stents, by virtue of their larger diameter and composition, do not develop encrustation at the same rate and have a longer patency.34 If metal stent obstruction does occur, it is usually the result of tumor ingrowth between the metal struts or tumor overgrowth at either end. Metal stents covered with a synthetic coating to prevent tumor ingrowth seem to have a similar or increased duration of patency (Fig. 45.4).35

Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis

Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, also known as Oriental cholangiohepatitis, is a clinical syndrome comprising repetitive episodes of bacterial cholangitis resulting from intrahepatic biliary obstruction with calcium bilirubinate stones or strictures or both. The bile ducts in the left lateral segment of the liver are often the only ducts affected or the most severely affected. This segment may be anatomically predisposed to stasis because of duct angulations slowing bile drainage. Chronic obstruction eventually causes permanent dilation of the proximal biliary tract, often filled with intrahepatic stones. Bile stasis and bacterial contamination may result in the development of multiple hepatic abscesses. Enterobacteriaceae bacteria are the most frequent organisms cultured from bile. P. aeruginosa may be seen in patients who have previously undergone endoscopic or surgical biliary intervention. Anaerobes are less common. Growth of multiple organisms, although unusual in other causes of cholangitis, often occurs in recurrent pyogenic cholangitis.36 Isolation of biliary parasites in patients with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis is common,37,38 but it is unclear whether the parasite is an etiologic agent or an incidental finding.

Preparation

Prophylactic antibiotics have been recommended to decrease the risk of cholangitis during ERCP in patients with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis.39 Magnetic resonance (MR) cholangiography before ERCP should be considered. The major advantage of MR cholangiography is complete visualization of the biliary tract including segments obstructed by calculi or strictures40 that may not be apparent by ERCP. Detailed knowledge of intrahepatic segment anatomy is necessary to correlate MR imaging to the opacified ducts at ERCP and guide endoscopic management.

Procedure

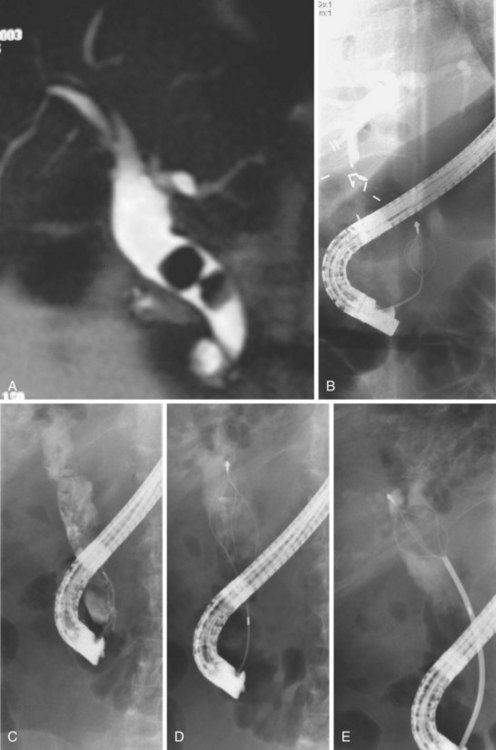

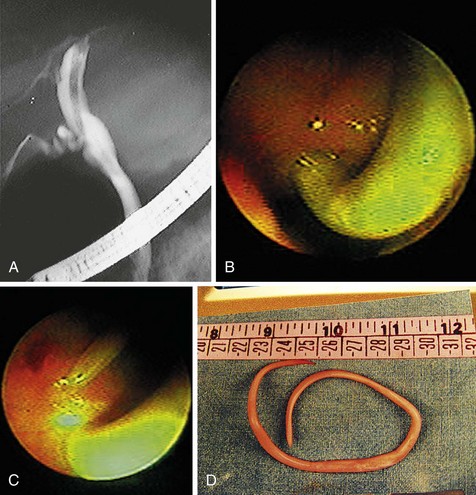

Cholangiography during ERCP also accurately documents duct dilation, intraductal stones, and gallstones (Fig. 45.5). The intrahepatic ducts appear straightened and acutely angulated at branches, likely secondary to periductal fibrosis. There is often distinct tapering of the intrahepatic ducts proximally, described as the “arrowhead” sign, and decreased duct branching. Complete occlusion of an intrahepatic duct by a stone may be represented by segmental absence of contrast material and is better assessed by MR cholangiography.

If the aforementioned methods are unsuccessful, choledochoscopy should be considered.

Complications

The clinical course may be complicated by recurrent sepsis, hepatic abscess rupture with peritonitis,37 portal pyelothrombophlebitis, and, rarely, hepatic failure.42 Patients may present with acute pancreatitis, presumably secondary to obstruction of the pancreatic duct by a stone or parasite, but this is uncommon. In the long-term, patients are at risk of cirrhosis, atrophy of hepatic segments supplied by thrombosed portal branches, clinical manifestations of portal hypertension, and cholangiocarcinoma.41,42

Outcomes

ERCP has been successfully used in the treatment of recurrent pyogenic cholangitis for 25 years.43 ERCP was traditionally used to provide a detailed “map” of the biliary tract, noting the location of stones and strictures, to guide definitive therapy. However, with the development of MR cholangiography, diagnostic ERCP should be reserved for situations in which MR imaging expertise is unavailable.40 Endoscopic sphincterotomy with stricture dilation and stone extraction is uncomplicated for extrahepatic disease. The soft pigment stones readily deform and fragment, enabling delivery into the duodenum.

Complete clearance of hepatolithiasis is attained in 96% of patients after an average of six treatments.44 However, one-third of patients have recurrent disease by 5 years. Cheung45 reported 190 patients with residual hepatolithiasis after surgical choledocholithotomy and choledochoscopic lithotripsy who were treated via a T-tube tract. Treatment consisted of sequential biliary stricture dilation with stent placement between dilation sessions. After the strictures were adequately treated, choledochoscopy and EHL were performed to fragment intrahepatic calculi with basket retrieval of stone debris. Complete clearance was achieved in 88% of patients; 15% of these patients developed evidence of recurrent disease during a mean follow-up period of 4 years. Complications were mild and included hemobilia and fever. Biliary enteric bypass procedures for repeated access to the intrahepatic ducts involve creation of a Roux-en-Y hepatojejunostomy or choledochojejunostomy with one jejunal limb brought to the skin as a cutaneous stoma46,47 or a jejunoduodenostomy.48 Treatment of strictures and stones is possible using a duodenoscope, gastroscope, or choledochoscope (Fig. 45.6). When treatment is complete, the stoma can be buried subcutaneously, but it may be reaccessed by a simple surgical procedure in the event of disease recurrence.

Avoidance of hepatic resection and resolution of hepatic abscesses can be achieved; however, repeat therapy or hepatic resection are most likely to be required as stones and strictures recur.47 Segmental hepatic resection is often used to treat localized disease, primarily involving the left lateral or right posterior segments. Initial stone clearance is 96% with a disease recurrence of 6% at 5 years.44 The complications are greater compared with hepatic-preserving procedures and include hepatic insufficiency, postoperative hemorrhage, and bile leak. Liver transplantation is rarely performed in patients with recurrent pyogenic cholangitis.49,50 Appropriate indications are advanced biliary cirrhosis or diffuse hepatic disease unresponsive to the aforementioned measures. The potential for disease recurrence in the transplanted liver is unknown. There is no evidence to support the use of long-term antibiotics or ursodeoxycholic acid in the management of recurrent pyogenic cholangitis.

Parasitic Cholangitis

Ascaris Cholangitis

A. lumbricoides exists worldwide but is most prevalent in Asia, Africa, and South America as a result of crowded living conditions and poor sanitation. Ova are passed in the human feces and are ingested on contaminated fruit or vegetables. Previous endoscopic or surgical sphincterotomy,51,52 bilioenteric bypass surgery,51 and cholecystectomy52 increase the likelihood of biliary involvement. A. lumbricoides causes inflammation of the bile duct and secondary bacterial cholangitis by allowing ascending bacterial contamination of bile, obstructing the bile duct and stimulating pigment stone formation. Migration into the gallbladder to cause acalculous or calculous cholecystitis seems to be facilitated by a low insertion of the cystic duct at the level of the ampulla and by pregnancy.53

Indications

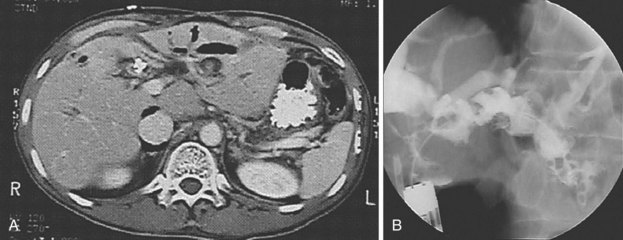

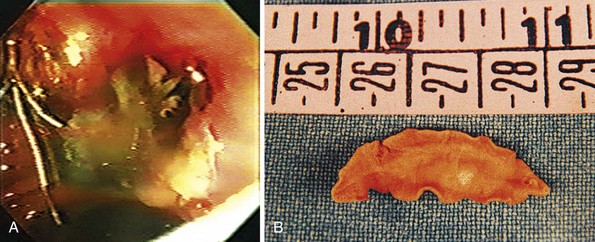

ERCP is indicated in Ascaris cholangitis to remove worms from the biliary tract when anthelmintic therapy is unsuccessful or after medical therapy when the dying worm releases numerous eggs, and these, combined with the worm’s own remnants, obstruct the biliary or pancreatic duct and act as a nidus for pigment stone formation (Fig. 45.7). The sequelae of Ascaris cholangitis, such as bile duct strictures and choledocholithiasis, may result in biliary obstruction necessitating endoscopic therapy.

Procedure

Complications

In addition to infecting the biliary tree, A. lumbricoides parasites also burrow through the bile duct wall into the liver parenchyma to form hepatic abscesses. Acute pancreatitis has been reported secondary to worms obstructing the pancreatic duct.52

Outcomes

ERCP is indicated for diagnosis and management of Ascaris cholangitis. ERCP enables sampling of bile to determine the presence of ova, which may be more sensitive than stool microscopy,54 and to show the mature parasite within the biliary system (Fig. 45.8). Endoscopic extraction of biliary A. lumbricoides is successful and safe in 99% of patients.52 Although endoscopic sphincterotomy increases the risk of reinfection, it is necessary for worm extraction in 95% of cases.55 Surgical removal of A. lumbricoides from the biliary tract was a common practice before the advent of therapeutic endoscopy. Present surgical indications include cholecystitis owing to worms or calculi and failure of endoscopic bile duct clearance.

Liver Fluke Cholangitis

Procedure

Outcomes

Anthelmintic therapy is indicated in all infected individuals. Given the potentially severe complications and ongoing parasite transmission, even asymptomatic individuals should receive eradication treatment. ERCP enables sampling of bile to show the presence of ova, which may be more sensitive than stool microscopy,54 and demonstration of the mature parasite within the biliary system. Placement of a nasobiliary tube to perform biliary infusion of povidone-iodine has been described in the management of F. hepatica cholangitis.58 Nine patients who had failed oral anthelmintic therapy became negative for stool ova after biliary administration of povidone-iodine. Surgical intervention is indicated for biliary or pancreatic obstruction after unsuccessful endoscopic therapy and for cholecystitis.

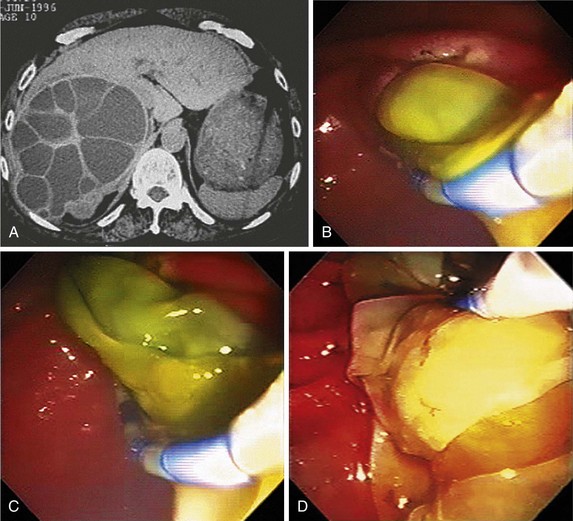

Echinococcal Cholangitis

Indications

The indications for ERCP in biliary echinococcosis are listed in Box 45.2.

Procedure

The goals of ERCP are to document suspected Echinococcus cholangitis and treat biliary obstruction.

Complications

E. multilocularis may invade into the portal venous system resulting in portal hypertension.61

Outcomes

Endoscopic management of biliary obstruction secondary to E. granulosus infection through extraction of hydatid debris or biliary endoprosthesis placement is successful at alleviating patient symptoms.60 Case reports have documented resolution of a hydatid cyst communicating with the biliary tree after endoscopic extraction of cyst material followed by instillation of hypertonic saline solution via a nasobiliary tube placed in the cyst cavity and administration of albendazole orally.62 In E. granulosus infection, approximately 30% of patients experience cure with medical therapy alone.63,64 Successful therapy is more likely with small, simple cysts and treatment duration greater than 3 months.63,65,66 Complete surgical excision by cystectomy, pericystectomy, or partial hepatic resection is usually curative in E. granulosus infection. Albendazole administered before surgery results in a higher number of nonviable cysts66,67 and may decrease the risk of local recurrence or intraperitoneal seeding should spillage of cyst contents occur. Surgical mortality is 1% to 2%.68 Complications include infection, bile leak, and leakage of cyst contents with hypersensitivity reaction and dissemination of disease.

Percutaneous evacuation with ultrasound-guided PAIR is widely used to treat unilocular E. granulosus cysts. Scolicidal agents employed for PAIR include 95% ethanol and hypertonic saline. Khuroo and associates69 randomly assigned 50 patients to undergo cystectomy or PAIR and receive albendazole. At a mean follow-up of 17 months, the cyst diameter was similar in the two groups, but the surgical arm had significantly more complications and a longer length of hospital stay. After PAIR, initial treatment failures occurred in less than 1%, and probability of relapse ranged from 1% to 4.5%. Complications of PAIR include hypersensitivity reaction, infection, intraabdominal seeding, and fistula formation to adjacent organs. In a review of 765 abdominal hydatid cysts treated with PAIR, anaphylaxis occurred in four instances with one death, and minor complications occurred in 14%.70

ERCP should be performed before protoscolicide administration to ensure there is no communication between the cyst and biliary tree because contact with protoscolicidal agents produces sclerosing cholangitis and pancreatitis. Treatment with albendazole at least 4 hours before PAIR and up to 4 weeks following has been recommended.70 The endoscopic management of E. multilocularis cholangitis consists of stent placement to relieve biliary obstruction. Sezgin and colleagues61 have published the largest case series of hepatic E. multilocularis complicated by biliary strictures. Seven of nine patients underwent successful stent placement. The stent provided adequate biliary drainage but was ineffective in treating biliary fistula disease present in two patients.

Radical surgery with complete excision of larvae tissue is the only curative therapy for E. multilocularis infection. Treatment with albendazole for an additional 2 years postoperatively decreases the risk of local recurrence.64,71 Patients deemed inoperable at diagnosis likely benefit from long-term albendazole therapy,71 and a combination of palliative resection, aimed at lessening the mass of larvae tissue, and benzimidazole therapy is advocated.72 Liver transplantation is a treatment option for unresectable alveolar echinococcosis. A retrospective study of European transplant centers reported 45 patients who underwent liver transplantation with an overall 5-year survival of 71% and disease-free 5-year survival of 58%.73 Given the high probability of graft recurrence, long-term benzimidazole therapy should be considered in posttransplant patients.

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Cholangiopathy

AIDS cholangiopathy is a syndrome of right upper quadrant pain, elevated alkaline phosphatase, and typical cholangiography findings associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Opportunistic infection of the biliary tract is likely a causative factor. Cryptosporidium, most commonly Cryptosporidium parvum, is isolated from the bile or stool in two-thirds of individuals with AIDS cholangiopathy,74 but other organisms have also been associated, including Microsporida, cytomegalovirus, Isospora, Cyclospora, and Mycobacterium avium intracellulare.75,76 Acalculous cholecystitis secondary to opportunistic infection of the gallbladder may occur alone or concomitant to cholangiopathy and is associated with similar underlying pathogens. Cholangiopathy is the AIDS-defining illness in a few patients, but most patients have had AIDS for at least 1 year.77

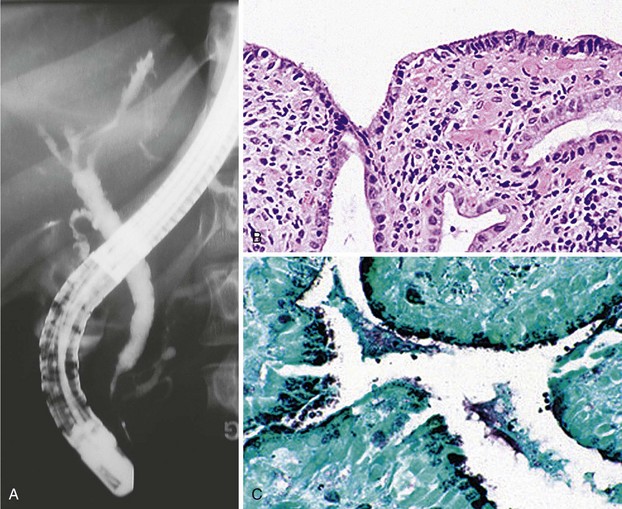

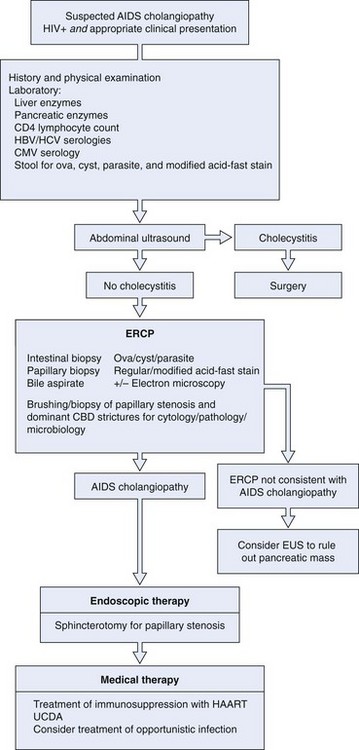

Indications

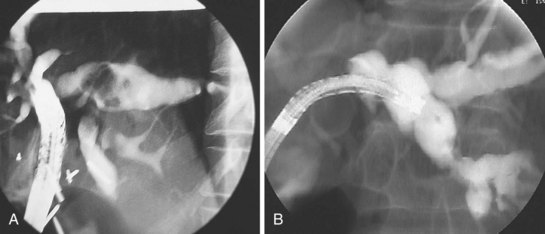

ERCP is the “gold standard” in diagnosing AIDS cholangiopathy (Fig. 45.10). The differential diagnosis of AIDS cholangiopathy and the management approach are shown in Box 45.3 and Fig. 45.11, respectively.

Box 45.3 Differential Diagnosis of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Cholangiopathy

Precautions

Protease inhibitors and benzodiazepines are both metabolized through the P-450 enzyme complex. Protease inhibitors decrease benzodiazepine metabolism, increasing their serum levels and potentiating their effects, including respiratory depression.78 Because midazolam and diazepam are commonly used for sedation during endoscopic procedures, endoscopists should be cognizant of this drug interaction while administering benzodiazepines in patients receiving protease inhibitors.

Procedure

Cholangiography findings have been described as sclerosing cholangitis with segmental stricture formation to create a beaded appearance similar to primary sclerosing cholangitis. The patterns of biliary tract strictures are listed in Table 45.1. Papillary stenosis with intrahepatic strictures is the most common pattern observed.75,77,79 Other reported cholangiography abnormalities include adherent polypoid filling defects; biopsy specimens of these defects show granulation tissue.80 Pancreatography is abnormal in one-half of patients with AIDS cholangiopathy, revealing pancreatic duct strictures in the head of the pancreas.75,81

Table 45.1 Cholangiography Findings in Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Cholangiopathy

| Finding | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Papillary stenosis and intrahepatic duct strictures | 33 |

| Papillary stenosis alone | 21 |

| Papillary stenosis and intrahepatic and extrahepatic duct strictures | 20 |

| Intrahepatic duct strictures alone | 12 |

| Intrahepatic and extrahepatic duct strictures | 8 |

| Extrahepatic duct strictures alone | 5 |

| Papillary stenosis and extrahepatic duct strictures | 1 |

Data from Benhamou Y, Caumes E, Gerosa Y, et al: AIDS-related cholangiopathy: Critical analysis of a prospective series of 26 patients. Dig Dis Sci 38:1113–1118, 1993; Bouche H, Housset C, Dumont JL, et al: AIDS-related cholangitis: Diagnostic features and course in 15 patients. J Hepatol 17:34–39, 1993; Cello JP: AIDS-related biliary tract disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 8:963, 1998; Ducreux M, Buffet C, Lamy P, et al: Diagnosis and prognosis of AIDS-related cholangitis. AIDS 9:875–880, 1995; Farman J, Brunetti J, Baer JW, et al: AIDS-related cholangiopancreatographic changes. Abdom Imaging 19:417–422, 1994.

Complications

Cholangitis with secondary fibrosis leads to bile duct stricture formation and papillary stenosis. Secondary biliary cirrhosis has not been described as a complication of AIDS cholangiopathy, perhaps because of the shortened life span of this patient population, but these patients may be at risk of cholangiocarcinoma.82

Outcomes

Aspiration of bile for culture and multiple biopsy specimens of the duodenum and papilla reveal an underlying pathogen in up to 92% of cases.81 One study reported that isolation of Cryptosporidium or cytomegalovirus was more common when intrahepatic duct irregularities were present on cholangiography.83 The medical management of AIDS cholangiopathy is divided into antimicrobial agents directed against the causative organism, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) directed against the underlying HIV infection, and ursodeoxycholic acid.

Case series assessing the effect of treatment of cytomegalovirus, C. parvum, and Microsporida on patient symptoms, liver enzymes, and cholangiography findings have not been encouraging.74,83,84 The use of HAART to restore the immune system has been effective in suppressing enteritis and possibly cholangiopathy associated with C. parvum and Microsporida, although eradication probably does not occur.85 Castiella and associates86 treated four patients with AIDS cholangiopathy with ursodeoxycholic acid (10 mg/kg body weight). At a mean follow-up of 4.5 months, improvement in symptoms and alkaline phosphatase levels was observed in all patients.

Endoscopic therapy has been the most extensively studied treatment in AIDS cholangiopathy. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with papillary stenosis results in improvement of abdominal pain in 32% to 100% of patients.81,83,87 Cello and Chan88 reported improvement in pain scores at a mean of 9.4 months after sphincterotomy; this did not correspond to an improvement in liver enzymes or cholangiography abnormalities, both of which appeared to worsen. Patient survival after a diagnosis of AIDS cholangiopathy is not affected by the pattern of cholangiogram abnormalities or the presence of an endoscopic sphincterotomy but appears to be most strongly associated with the administration of HAART.89

Cholecystitis

Procedure

Outcomes

Cholecystectomy is the definitive therapy. Although patients may recover from an episode of acute cholecystitis, the risk of recurrent symptoms is 70% within the next 2 years.92 Patients without serious concomitant medical problems should undergo cholecystectomy during the same hospital admission, usually 24 to 48 hours after admission. In particular, diabetics, given their increased risk of gallbladder necrosis and perforation, should be considered for cholecystectomy after their first attack of cholecystitis. Patients who are medically unfit for surgery and do not improve with supportive therapy require gallbladder drainage; this is generally achieved by percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement, although successful endoscopic drainage of the gallbladder has been described. Placement of a biliary endoprosthesis into the gallbladder during ERCP can alleviate symptoms resulting from recurrent biliary colic, calculous cholecystitis, acalculous cholecystitis, and gallbladder perforation (Fig. 45-12).91–93 Endoscopic gallbladder drainage can be performed in the presence of coagulopathy and ascites when percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement is contraindicated.

1 Draganov P, Cotton PB. Iodinated contrast sensitivity in ERCP. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1398-1401.

2 Tham TC, Vandervoort J, Wong RC, et al. Safety of ERCP during pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:308-311.

3 van Lent AU, Bartelsman JF, Tytgat GN, et al. Duration of antibiotic therapy for cholangitis after successful endoscopic drainage of the biliary tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:518-522.

4 Wang P, Li ZS, Liu F, et al. Risk factors for ERCP-related complications: A prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:31-40.

5 Williams EJ, Taylor S, Fairclough P, et al. Risk factors for complication following ERCP: Results of a large-scale, prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:793-801.

6 Vandervoort J, Soetikno RM, Tham TC, et al. Risk factors for complications after performance of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:652-656.

7 Lai EC, Lo CM, Choi TK, et al. Urgent biliary decompression after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Am J Surg. 1989;157:121-125.

8 Motte S, Deviere J, Dumonceau JM, et al. Risk factors for septicemia following endoscopic biliary stenting. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1374-1381.

9 Struelens MJ, Rost F, Deplano A, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia after biliary endoscopy: An outbreak investigation using DNA macrorestriction analysis. Am J Med. 1993;95:489-498.

10 Gregg JA, De Girolami P, Carr-Locke DL. Effects of sphincteroplasty and endoscopic sphincterotomy on the bacteriologic characteristics of the common bile duct. Am J Surg. 1985;149:668-671.

11 Cetta F. Do surgical and endoscopic sphincterotomy prevent or facilitate recurrent common duct stone formation? Arch Surg. 1993;128:329-336.

12 Mandell G, Bennett J, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious disease, ed 5, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

13 Rerknimitr R, Fogel EL, Kalayci C, et al. Microbiology of bile in patients with cholangitis or cholestasis with and without plastic biliary endoprosthesis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:885-889.

14 Gigot JF, Leese T, Dereme T, et al. Acute cholangitis: Multivariate analysis of risk factors. Ann Surg. 1989;209:435-438.

15 Ernest van Heurn LW, Saing H, Tam PK. Cholangitis after hepatic portoenterostomy for biliary atresia: A multivariate analysis of risk factors. J Pediatr. 2003;142:566-571.

16 Baker AR, Neoptolemos JP, Carr-Locke DL, et al. Sump syndrome following choledochoduodenostomy and its endoscopic treatment. Br J Surg. 1985;72:433-435.

17 Caroli-Bosc FX, Demarquay JF, Peten EP, et al. Endoscopic management of sump syndrome after choledochoduodenostomy: Retrospective analysis of 30 cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:180-183.

18 Mavrogiannis C, Liatsos C, Romanos A, et al. Sump syndrome: Endoscopic treatment and late recurrence. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:972-975.

19 Banerjee S, Shen B, Baron TH, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:791-798.

20 Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart Association: A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116:1736-1754.

21 Leese T, Neoptolemos JP, Baker AR, et al. Management of acute cholangitis and the impact of endoscopic sphincterotomy. Br J Surg. 1986;73:988-992.

22 Leung JW, Chung SC, Sung JJ, et al. Urgent endoscopic drainage for acute suppurative cholangitis. Lancet. 1989;1:1307-1309.

23 Lai EC, Mok FP, Tan ES, et al. Endoscopic biliary drainage for severe acute cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1582-1586.

24 Lee DW, Chan AC, Lam YH, et al. Biliary decompression by nasobiliary catheter or biliary stent in acute suppurative cholangitis: A prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:361-365.

25 Neuhaus H, Zillinger C, Born P, et al. Randomized study of intracorporeal laser lithotripsy versus extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy for difficult bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:327-334.

26 Binmoeller KF, Bruckner M, Thonke F, et al. Treatment of difficult bile duct stones using mechanical, electrohydraulic and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1993;25:201-206.

27 Cotton PB, Kozarek RA, Schapiro RH, et al. Endoscopic laser lithotripsy of large bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1128-1133.

28 Bergman JJ, Rauws EA, Tijssen JG, et al. Biliary endoprostheses in elderly patients with endoscopically irretrievable common bile duct stones: Report on 117 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:195-201.

29 Chopra KB, Peters RA, O’Toole PA, et al. Randomised study of endoscopic biliary endoprosthesis versus duct clearance for bile duct stones in high-risk patients. Lancet. 1996;348:791-793.

30 Baron TH, Schroeder PL, Schwartzberg MS, et al. Resolution of Mirizzi’s syndrome using endoscopic therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:343-345.

31 Tsuyuguchi T, Saisho H, Ishihara T, et al. Long-term follow-up after treatment of Mirizzi syndrome by peroral cholangioscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:639-644.

32 Hui CK, Lai KC, Wong WM, et al. A randomised controlled trial of endoscopic sphincterotomy in acute cholangitis without common bile duct stones. Gut. 2002;51:245-247.

33 Chang WH, Kortan P, Haber GB. Outcome in patients with bifurcation tumors who undergo unilateral versus bilateral hepatic duct drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:354-362.

34 Speer AG, Cotton PB, Rode J, et al. Biliary stent blockage with bacterial biofilm: A light and electron microscopy study. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:546-553.

35 Isayama H, Komatsu Y, Tsujino T, et al. A prospective randomised study of “covered” versus “uncovered” diamond stents for the management of distal malignant biliary obstruction. Gut. 2004;53:729-734.

36 Wilson MK, Stephen MS, Mathur M, et al. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis or “oriental cholangiohepatitis” in occidentals: Case reports of four patients. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:649-652.

37 Chou ST, Chan CW. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: A necropsy study. Pathology. 1980;12:415-428.

38 Lim JH. Oriental cholangiohepatitis: Pathologic, clinical, and radiologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:1-8.

39 Lam SK, Wong KP, Chan PK, et al. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: A study by endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:1196-1203.

40 Park MS, Yu JS, Kim KW, et al. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis: Comparison between MR cholangiography and direct cholangiography. Radiology. 2001;220:677-682.

41 Sheen-Chen SM, Chou FF, Lee CM, et al. The management of complicated hepatolithiasis with intrahepatic biliary stricture by the combination of T-tube tract dilation and endoscopic electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:168-171.

42 Kusano S, Okada Y, Endo T, et al. Oriental cholangiohepatitis: Correlation between portal vein occlusion and hepatic atrophy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:1011-1014.

43 Lam SK. A study of endoscopic sphincterotomy in recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Br J Surg. 1984;71:262-266.

44 Otani K, Shimizu S, Chijiiwa K, et al. Comparison of treatments for hepatolithiasis: Hepatic resection versus cholangioscopic lithotomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;189:177-182.

45 Cheung MT. Postoperative choledochoscopic removal of intrahepatic stones via a T tube tract. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1224-1228.

46 Gott PE, Tieva MH, Barcia PJ, et al. Biliary access procedure in the management of oriental cholangiohepatitis. Am Surg. 1996;62:930-934.

47 Stain SC, Incarbone R, Guthrie CR, et al. Surgical treatment of recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Arch Surg. 1995;130:527-532.

48 Ramesh H, Prakash K, Kuruvilla K, et al. Biliary access loops for intrahepatic stones: Results of jejunoduodenal anastomosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 2003;73:306-312.

49 Strong RW, Chew SP, Wall DR, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatolithiasis. Asian J Surg. 2002;25:180-183.

50 Sperling RM, Koch J, Sandhu JS, et al. Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis in Asian immigrants to the United States: Natural history and role of therapeutic ERCP. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:865-871.

51 Gupta R, Agarwal DK, Choudhuri GD, et al. Biliary ascariasis complicating endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis in India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1072-1073.

52 Sandouk F, Haffar S, Zada MM, et al. Pancreatic-biliary ascariasis: Experience of 300 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2264-2267.

53 Khuroo MS, Zargar SA, Yattoo GN, et al. Sonographic findings in gallbladder ascariasis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1992;20:587-591.

54 Chan HH, Lai KH, Lo GH, et al. The clinical and cholangiographic picture of hepatic clonorchiasis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:183-186.

55 Alam S, Mustafa G, Ahmad N, et al. Presentation and endoscopic management of biliary ascariasis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;38:631-635.

56 Leung JW, Sung JY, Banez VP, et al. Endoscopic cholangiopancreatography in hepatic clonorchiasis—a follow-up study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:360-363.

57 Dias LM, Silva R, Viana HL, et al. Biliary fascioliasis: Diagnosis, treatment and follow-up by ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:616-620.

58 Dowidar N, El Sayad M, Osman M, et al. Endoscopic therapy of fascioliasis resistant to oral therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:345-351.

59 Doyle TC, Roberts-Thomson IC, Dudley FJ. Demonstration of intrabiliary rupture of hepatic hydatid cysts by retrograde cholangiography. Australas Radiol. 1988;32:92-97.

60 Giouleme O, Nikolaidis N, Zezos P, et al. Treatment of complications of hepatic hydatid disease by ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:508-510.

61 Sezgin O, Altintas E, Saritas U, et al. Hepatic alveolar echinococcosis: Clinical and radiologic features and endoscopic management. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:160-167.

62 Dzirlo L, Wasilewski M, Poeschl E, et al. Liver cyst of Echinococcus granulosus with rupture into the biliary tree—successful endoscopic and pharmaceutical treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1674-1675.

63 Horton RJ. Albendazole in treatment of human cystic echinococcosis: 12 years of experience. Acta Trop. 1997;64:79-93.

64 Guidelines for treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:231-242.

65 Liu Y, Wang X, Wu J. Continuous long-term albendazole therapy in intraabdominal cystic echinococcosis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2000;113:827-832.

66 Gil-Grande LA, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F, Prieto JG, et al. Randomised controlled trial of efficacy of albendazole in intra-abdominal hydatid disease. Lancet. 1993;342:1269-1272.

67 Aktan AO, Yalin R. Preoperative albendazole treatment for liver hydatid disease decreases the viability of the cyst. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:877-879.

68 Balik AA, Basoglu M, Celebi F, et al. Surgical treatment of hydatid disease of the liver: Review of 304 cases. Arch Surg. 1999;134:166-169.

69 Khuroo MS, Wani NA, Javid G, et al. Percutaneous drainage compared with surgery for hepatic hydatid cysts. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:881-887.

70 Filice C, Brunetti E. Percutaneous drainage of hydatid cysts. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:392. author reply 392–393

71 Ammann RW. Improvement of liver resectional therapy by adjuvant chemotherapy in alveolar hydatid disease. Swiss Echinococcosis Study Group (SESG). Parasitol Res. 1991;77:290-293.

72 Ishizu H, Uchino J, Sato N, et al. Effect of albendazole on recurrent and residual alveolar echinococcosis of the liver after surgery. Hepatology. 1997;25:528-531.

73 Koch S, Bresson-Hadni S, Miguet JP, et al. Experience of liver transplantation for incurable alveolar echinococcosis: A 45-case European collaborative report. Transplantation. 2003;75:856-863.

74 Forbes A, Blanshard C, Gazzard B. Natural history of AIDS related sclerosing cholangitis: A study of 20 cases. Gut. 1993;34:116-121.

75 Farman J, Brunetti J, Baer JW, et al. AIDS-related cholangiopancreatographic changes. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:417-422.

76 Pol S, Romana CA, Richard S, et al. Microsporidia infection in patients with the human immunodeficiency virus and unexplained cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:95-99.

77 Cello JP. AIDS-related biliary tract disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1998;8:963.

78 Preston SL, Postelnick M, Purdy BD, et al. Drug interactions in HIV-positive patients initiated on protease inhibitor therapy. AIDS. 1998;12:228-230.

79 Daly CA, Padley SP. Sonographic prediction of a normal or abnormal ERCP in suspected AIDS related sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:618-621.

80 Collins CD, Forbes A, Harcourt-Webster JN, et al. Radiological and pathological features of AIDS-related polypoid cholangitis. Clin Radiol. 1993;48:307-310.

81 Bouche H, Housset C, Dumont JL, et al. AIDS-related cholangitis: Diagnostic features and course in 15 patients. J Hepatol. 1993;17:34-39.

82 Hocqueloux L, Gervais A. Cholangiocarcinoma and AIDS-related sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:1006-1007.

83 Benhamou Y, Caumes E, Gerosa Y, et al. AIDS-related cholangiopathy: Critical analysis of a prospective series of 26 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1113-1118.

84 Hashmey R, Smith NH, Cron S, et al. Cryptosporidiosis in Houston, Texas: A report of 95 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1997;76:118-139.

85 Carr A, Marriott D, Field A, et al. Treatment of HIV-1-associated microsporidiosis and cryptosporidiosis with combination antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 1998;351:256-261.

86 Castiella A, Iribarren JA, Lopez P, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of AIDS-associated cholangiopathy. Am J Med. 1997;103:170-171.

87 Ducreux M, Buffet C, Lamy P, et al. Diagnosis and prognosis of AIDS-related cholangitis. AIDS. 1995;9:875-880.

88 Cello JP, Chan MF. Long-term follow-up of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography sphincterotomy for patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome papillary stenosis. Am J Med. 1995;99:600-603.

89 Ko WF, Cello JP, Rogers SJ, et al. Prognostic factors for the survival of patients with AIDS cholangiopathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2176-2181.

90 Feretis C, Apostolidis N, Mallas E, et al. Endoscopic drainage of acute obstructive cholecystitis in patients with increased operative risk. Endoscopy. 1993;25:392-395.

91 Johlin FCJr, Neil GA. Drainage of the gallbladder in patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis by transpapillary endoscopic cholecystotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:645-651.

92 Thistle JL, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, et al. The natural history of cholelithiasis: The National Cooperative Gallstone Study. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:171-175.

93 Baron TH, Farnell MB, Leroy AJ. Endoscopic transpapillary gallbladder drainage for closure of calculous gallbladder perforation and cholecystoduodenal fistula. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:753-755.