Chapter 13 Infections of Bone and Joint

Although bone and joint infection remains a serious problem, acute, fulminating bone involvement is seen much less frequently than in the past. The cause of these disorders is usually bacterial. Although more effective antibiotics continue to be developed, treatment of the established chronic infection remains a challenging problem.

Acute Osteomyelitis

CLINICAL FEATURES

In general, acute hematogenous osteomyelitis occurs primarily in late infancy and at puberty and is often preceded by signs of systemic disease and/or general sepsis for several days. The lower extremity is most commonly affected, and a mild limp may develop. Anorexia, nausea, malaise, irritability, and fever are present, usually during the acute phase. This stage of the disease may last for several days before bone pain and local overlying inflammation appear. Fever, chills, and diaphoresis are the usual systemic complaints. Pain, bone tenderness, heat, and swelling of the soft tissue are the classic physical findings. There is often limitation of motion of an adjacent joint caused by a sympathetic effusion. (Remember: an unexplained fever with bone pain in the child is osteomyelitis until proven otherwise.)

Tuberculous, fungal, and rickettsial causes of osteomyelitis generally have an insidious onset. These diseases are more common in patients who are immunologically depressed, who have other underlying diseases, such as alcoholism, or those whose immune systems have been altered by immunosuppressive therapy or human immunodeficiency virus. The primary source of these infections is often pulmonary, and a low-grade fever, weight loss, anorexia, and chronic cough or sputum production may be present. Tuberculous osteomyelitis may involve the vertebral column with pathologic fractures of the involved vertebrae. This usually results in angular kyphosis of the spine or so-called Pott’s disease (Fig. 13-1).

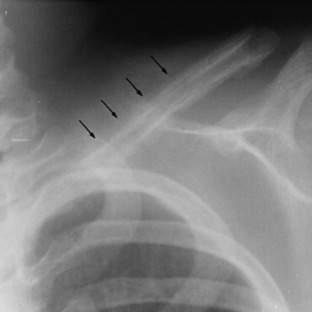

ROENTGENOGRAPHIC FEATURES

The classic roentgenographic finding of acute osteomyelitis in childhood is deep, circumferential soft tissue swelling with obliteration of muscular planes. Spotty rarefactions representing early destruction may appear within 7 to 12 days in the affected bone. Shortly after this, periosteal new bone formation becomes evident and indicates that the infection has spread through the cortex (Fig. 13-2). Plain roentgenograms are of less value in adult osteomyelitis because significant bony changes may not be apparent until at least 50% of bone destruction has occurred, which may be 2 to 4 weeks into the illness. In the spine, infection can involve the vertebral body or the disc space. Disc space infections are uncommon but do occur occasionally in children and in patients who have undergone surgery on the intervertebral disc. In these cases, the roentgenographic changes are vertebral end-plate irregularities and disc space narrowing. Eventually, new bone proliferation occurs, and frequently complete fusion of the disc is the result. In osteomyelitis of the vertebral body, the roentgenographic changes are those of bone destruction with loss of vertebral height. Paravertebral swelling and/or paraspinal masses may also be occasionally demonstrated.

Subacute Osteomyelitis

Brodie’s abscess is a form of subacute osteomyelitis in which a small, localized, painful cavity develops in the metaphysis. The lesion is surrounded by dense, sclerotic bone (Fig. 13-3). The disorder is insidious in onset and lacks the systemic symptoms of acute osteomyelitis.

Chronic Osteomyelitis

This disorder can occasionally be the end result of an acute hematogenous osteomyelitis, but it is more commonly caused by an open fracture or wound and rarely by a surgical procedure. It is often seen in the lower extremities of patients with diabetes. All forms of chronic osteomyelitis are difficult to eradicate. The cause is often polymicrobial.

ROENTGENOGRAPHIC FINDINGS

Chronic osteomyelitis usually appears as irregular sclerotic bone that may contain several areas of radiolucency. Irregular areas of destruction are commonly present, and there is often periosteal thickening (Fig. 13-4). Small, dense areas of dead bone called sequestra may be present. If the acute hematogenous osteomyelitis has been extensive, the entire shaft may become a sequestrum. This dead bone is then surrounded by a new shell of bone called the involucrum. Fortunately, this extensive involvement is rarely seen in Western society.

DIAGNOSIS

Cultures of the blood or of the lesion are essential to determine the exact causative agent and to institute the proper antimicrobial therapy. Blood cultures are positive in approximately 50% of children with acute osteomyelitis, but are frequently negative in adults. Every attempt should be made to isolate the organism. Needle aspiration of the site may be attempted, but this is sometimes inadequate. Biopsy may be needed. If a primary focus can be identified, blood samples for a smear, Gram stain, and culture and sensitivity should be taken from this site. Cultures of chronic sinus tract drainage frequently are not representative of the cause of the chronic osteomyelitis, and deep cultures of the involved bone should be obtained. The laboratory workup should include a sedimentation rate determination and a complete blood cell count (CBC) in addition to the above cultures. There is usually a leukocytosis and an elevation of the ESR. The ESR and C-reactive protein level are sometimes useful to follow the patient’s progress during treatment.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The clinical picture of patients with acute rheumatic fever, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis may mimic that seen in acute septic arthritis. Synovial fluid examination is helpful. The diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever is based on Jones’ criteria of major and minor manifestations (Table 13-1).

| Major Manifestations |

| Carditis |

| Polyarthritis |

| Chorea |

| Erythema marginatum |

| Subcutaneous nodules |

| Minor Manifestations |

| Arthralgia |

| Fever |

| Prolonged PR interval |

| Elevated ESR, C-reactive protein |

| Supporting evidence of previous group A streptococcal infection |

| • Positive throat culture or rapid streptococcal antigen test |

| • Elevated or rising streptococcal antibody titer |

| NOTE: The presence of two major or one major and two minor manifestations indicates a high probability of acute rheumatic fever if supported by evidence of preceding group A streptococcal infection. |

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

If necessary, changes are made in the antibiotic coverage when the offending organism is identified. The sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels are followed during treatment. IV antibiotic coverage is usually continued for 4 weeks, but each case should be treated individually, and there is no consensus regarding the route and length of antibiotic coverage. Treatment for the subacute form is essentially the same.

Septic Arthritis

Gonococcal infection often leads to a distinct clinical syndrome and is discussed separately.

SPECIAL STUDIES

Roentgenographic findings early in the disease process are usually minimal and consist primarily of distention of the joint capsule. The peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count is markedly elevated as a rule, and blood cultures may be positive. The sedimentation rate is generally high, but neonates and geriatric patients may show only minimal laboratory abnormalities. Bone scanning and other studies are of limited value but may be very helpful in the evaluation of the patient whose symptoms are of uncertain cause.

TREATMENT

Treatment should begin immediately after cultures to prevent joint destruction and, in the case of the hip joint, dislocation (see Chapter 10). Rest and immobilization diminish the pain. The definitive antibiotic therapy depends on Gram stain and culture results. The IV route should always be used. Intraarticular injection is unnecessary because most antibiotics readily pass through the synovial membrane. Direct instillation may even provoke an inflammatory synovitis.

Special Problems

CELLULITIS

The offending organism is usually hemolytic streptococcus, although S. aureus, and, rarely, Gram-negative rods may be causative. The clinical presentation varies depending on the organism, but streptococcus usually causes a superficial warm, tender erythematous lesion characterized by an elevated, indurated margin. Vesicle formation may occur. Samples for Gram stain and culture may be obtained from this fluid or any local drainage. MRI may rarely be needed to determine the extent of soft tissue involvement and to rule out bony involvement.

GAS GANGRENE

CLINICAL FEATURES

The more severe forms are accompanied by chills, fever, tachycardia, delirium, and all of the other signs of a rapidly progressing infection. Renal shutdown and death may occur. The involved skin and muscle undergo further necrosis, and vesicles appear in the infected area.

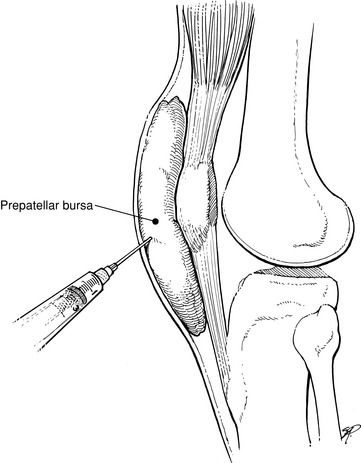

SEPTIC BURSITIS

TREATMENT

The bursa is aspirated and the fluid evaluated in the standard manner by Gram stain, culture, and sensitivity (Fig. 13-5). Blood cultures, blood counts, and sedimentation rates are also performed as indicated. (NOTE: It is important not to aspirate the joint itself. Passing the needle through the area of cellulitis and then into the joint could spread the infection into the joint.)

PROSTHETIC JOINT INFECTION

Fewer than 1% of joint replacements become infected, but the complication can be disastrous to the joint and difficult to cure. It may occur at any time after surgery. Early involvement is usually the result of skin contamination, often by coagulase-negative staphylococci. Later, the source is hematogenous, with a variety of pathogens being causative. Joints that have had previous surgery are also more predisposed to infection.

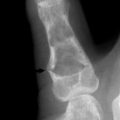

PENETRATING WOUNDS

BITE WOUNDS

Human bites require especially careful evaluation and examination. The most common site of injury is a closed fist that has struck the mouth (see Chapter 7). The injury that often occurs is a laceration over the metacarpophalangeal joint that may disrupt the extensor tendon and even penetrate into bone (Fig. 13-6). The wound may be small, and if the hand is examined with the fingers extended, the true extent of the injury may be overlooked because the injury was sustained with the fingers flexed. If joint involvement is noted, extra care is taken to ensure good cleansing and debridement. The wound should be treated open. Antibiotics are administered, and the wound is followed closely. The most common infecting organisms are S. aureus, streptococci, and anaerobes found in the normal flora of the human mouth. In addition, prophylactic therapy is indicated for those who are bitten by individuals with HIV or hepatitis B.

Altemeier WA, Fullen WD. Prevention and treatment of gas gangrene. JAMA. 1971;217:806-813.

Boll KL, Jurik AG. Sternal osteomyelitis in drug addicts. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:328-329.

Edson RS, Terrell CL. The aminoglycosides. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:1158-1164.

Emmons CW, Binford CH, Utz JP. Medical mycology, ed 2, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1970.

Gentry LO. Overview of osteomyelitis. Orthop Rev. 1987;16:255-258.

Green M, Nyhan WLJr, Fousek MD. Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis. Pediatrics. 1956;16:368-382.

Hoeprich PD. Infectious diseases. Hagerstown, Md: Harper & Row, 1972.

Holzman RS, Bishko F. Osteomyelitis in heroin addicts. Ann Intern Med. 1971;75:693-696.

Nade S. Septic arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2003;17:183-200.

Presutti RJ. Prevention and treatment of dog bites. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63:1567-1572.

Tay BK, Deckey J, Hu SS. Spinal infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:188-197.

Thompson RL, Wright AJ. Cephalosporin antibiotics. May Clin Proc. 1983;58:79-87.

Wright AJ, Wilkowske CJ. The penicillins. Mayo Clin Proc. 1987;62:806-820.

Wright AJ, Wilkowski CJ. The penicillins. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:1047-1063.