CHAPTER 13 INFECTION AND INFLAMMATION

INFECTION

Infection is common in the ICU and may be the primary cause of a patient’s admission, or may occur as a secondary phenomenon in patients who are already critically ill and whose normal barriers to infection are impaired. Factors that predispose to infection in critically ill patients are shown in Box 13.1. (See also Infection control, p. 19)

Box 13.1 Factors predisposing to infection in critical illness

Effects of sedative and analgesic agents (suppressed cough reflex, GI stasis, etc.)

Vascular catheters, urinary catheters and drains

Poor nutrition and impaired tissue healing

Immune suppressive effects of drugs

Increased risk of cross-infection

Prolonged broad spectrum antibiotics selecting out resistant and other organisms

SYSTEMIC INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE SYNDROME (SIRS)

It is now recognized that many processes (including infection) may trigger activation of endothelial cells, white cells, platelets and other cells, leading to the release of proinflammatory mediators, including platelet-activating factor (PAF), tumour necrosis factor (TNFα), interleukins, chemokines and other inflammatory mediators. These have effects such as increased vascular permeability (capillary leak), vasodilatation, sequestration of neutrophils, platelet adhesion and activation of complement systems. Simultaneous activation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways may lead to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and failure of the microcirculation. Indeed, in sepsis, the coagulation and inflammatory pathways are inextricably linked and mutually activated.

DEFINITIONS

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)

The systemic inflammatory response syndrome can be said to exist when two of the criteria listed in Box 13.2 are present, in the absence of a documented infection.

Sepsis

Features of SIRS, together with a documented infection. The infection may be bacterial, viral, fungal, parasitic or other organism. Difficulty may sometimes arise in patients with positive cultures in distinguishing between clinically insignificant colonization and true infection (see below).

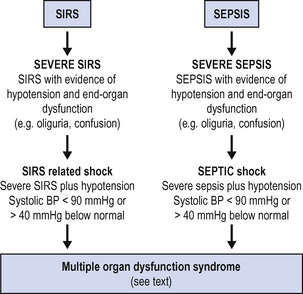

Both SIRS and sepsis may vary in severity from mild to severe, and both may progress to multiorgan dysfunction. Parallel definitions may be used, as shown in Fig. 13.1.

DISTINGUISHING INFECTION

In view of the similarities in the clinical picture produced by SIRS and sepsis (above), the problem may arise as how to distinguish infection. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a commonly used marker of infection but is not specific. Procalcitonin is an alternative marker that is thought to be more specific for infection, but is not yet widely available.

antigen tests, antibody titres, e.g. diagnosis of fungal infection esp. Candida, Aspergillus (24–48 h).

antigen tests, antibody titres, e.g. diagnosis of fungal infection esp. Candida, Aspergillus (24–48 h).SEPSIS CARE BUNDLES

Recent international consensus guidelines on the management of sepsis in critical care have been widely adopted (Table 13.1).

TABLE 13.1 Guidelines for initial treatment of sepsis. Adapted from surviving sepsis campaign1

| Initial resuscitation | Resuscitation goals |

|---|---|

| Begin resuscitation immediately in patients with hypotension or elevated serum lactate >4 mmol/L, do not delay pending ICU admission | CVP 8–12 mm Hg Mean arterial pressure > 65 mmHg Urine output >0.5 mL kg−1 h−1 Central venous (SVC) oxygen saturation > 70% or mixed venous > 65% |

| Diagnosis Obtain appropriate cultures before starting antibiotics provided this does not significantly delay antimicrobial administration |

Obtain two or more blood cultures (BC) One or more BCs should be percutaneous One BC from each vascular access device in place > 48 h Culture other sites as clinically indicated Perform imaging studies promptly to confirm any source of infection |

| Antibiotic therapy Begin intravenous antibiotics as early as possible and always within the first hour of recognizing severe sepsis and septic shock |

Use broad-spectrum antibiotics, one or more agents active against likely pathogens and with good penetration into presumed site of infection Reassess antimicrobial regimen daily to optimize efficacy, prevent resistance, avoid toxicity, and minimize costs Duration of therapy typically limited to 7–10 days; longer if response is slow or there are undrainable foci of infection or immunological deficiencies Stop antimicrobial therapy if cause is found to be non-infectious |

| Source identification and control A specific anatomic site of infection should be established as rapidly as possible and within first 6 h of presentation (see below). |

Formally evaluate patient for a focus of infection amenable to source control measures, e.g. abscess drainage, tissue debridement Implement source control measures as soon as possible following successful initial resuscitation (exception: infected pancreatic necrosis, where evidence suggests that surgical intervention is best delayed) Choose source control measure with maximum efficacy and minimal physiologic upset Remove intravascular access devices if potentially infected |

While much of the evidence is low level (based on expert opinion), the recommendations also include some high level evidence, the document as a whole forms a rational and coherent approach to the management of the patient with sepsis. Central to these sepsis care bundles is the need for early effective resuscitation, early effective antibiotic therapy and source control, and where possible, the use of an appropriate ‘biological response modifier’. Currently, activated protein C, (drotrecogin alpha), is the only such agent available (see Septic shock below). The key recommendations are summarized in Table 13.1.

SEPTIC SHOCK

Resuscitation and stabilization

If end-organ failure is compromising respiration (respiratory failure, severe confusion, etc.), early consideration should be given to securing the airway and instituting artificial ventilation. There is a risk, however, that the drugs used to facilitate intubation may cause circulatory collapse. (See Intubation, p. 398.) Therefore, where ventilation is not required immediately, it is often wiser to institute fluid resuscitation prior to attempting intubation and to insert an arterial line to provide accurate blood pressure monitoring. If peripheral arterial cannulation is not feasible, consider femoral or brachial artery.

Establish invasive monitoring, arterial line and CVP. Consider cardiac output monitoring, central venous saturation monitoring (see p. 74).

Establish invasive monitoring, arterial line and CVP. Consider cardiac output monitoring, central venous saturation monitoring (see p. 74). Optimize volume loading. Initially aim for a CVP 8–12 mmHg depending on patient’s condition and response, (10–15 mmHg in a ventilated patient). Above this level, it is unlikely that additional fluid loading will produce any further increase in left ventricular stroke volume index.

Optimize volume loading. Initially aim for a CVP 8–12 mmHg depending on patient’s condition and response, (10–15 mmHg in a ventilated patient). Above this level, it is unlikely that additional fluid loading will produce any further increase in left ventricular stroke volume index. If there is evidence of significant myocardial depression (low MAP with high CVP; low CI or SVI where monitoring is available), consider addition of an inotrope e.g. dobutamine / adrenaline (epinephrine) to support cardiac output. (See Cardiovascular system, p. 82.)

If there is evidence of significant myocardial depression (low MAP with high CVP; low CI or SVI where monitoring is available), consider addition of an inotrope e.g. dobutamine / adrenaline (epinephrine) to support cardiac output. (See Cardiovascular system, p. 82.) Maintain adequate tissue perfusion pressure (MAP ⩾ 65 mmHg). If MAP remains low despite adequate volume loading and cardiac output, add a vasoconstrictor, e.g. noradrenaline (norepinephrine).

Maintain adequate tissue perfusion pressure (MAP ⩾ 65 mmHg). If MAP remains low despite adequate volume loading and cardiac output, add a vasoconstrictor, e.g. noradrenaline (norepinephrine). Vasopressin infusion at physiological replacement doses. Vasopressin levels can become rapidly depleted in septic shock. Consider vasopressin as a second line vasopressor treatment. (See Optimizing perfusion pressure, p. 85.)

Vasopressin infusion at physiological replacement doses. Vasopressin levels can become rapidly depleted in septic shock. Consider vasopressin as a second line vasopressor treatment. (See Optimizing perfusion pressure, p. 85.)Complications

The specific complications and pattern of organ dysfunction varies from patient to patient. Many patients require renal support, some may develop prolonged GI tract failure, and a large proportion develop ARDS or coagulopathy. Some develop multiple organ dysfunction and multiple organ failure. Specific supportive measures for each system are required (see relevant sections).

INVESTIGATION OF UNEXPLAINED SEPSIS

Any patient in the ICU with unexplained ‘sepsis’ or rising markers of infection should have a thorough examination to identify possible sources. Appropriate microbiological samples should be obtained prior to the institution of antibiotic therapy. These should ideally include ‘clean stab’ blood cultures from a peripheral vein (in addition to cultures from any existing cannulae), sputum or BAL for microscopy and culture. Urine and any drain fluids should also be cultured. Additional investigations will be guided by the clinical picture (Table 13.2). It is important to repeat blood cultures and other microbiological investigations regularly to help make a diagnosis and to facilitate antibiotic de-escalation. (See also Distinguishing infection above.)

| Potential source | Investigation |

|---|---|

| Catheter-related | Blood cultures from catheters / peripheral stab. Request differential cultures Change indwelling vascular catheters and culture tips |

| Embolic | Serial blood cultures Precordial or transoesophageal echocardiography |

| Chest | CXR Tracheal aspirates for culture Bronchoscopy + BAL Tap and culture pleural fluid CT scan |

| Abdomen and pelvis | Amylase Culture drain fluids (fresh samples) Tap and culture ascites Plain abdominal X-ray Abdominal and pelvic ultrasound / CT scan Laparotomy |

| Urinary tract | Urine microscopy and culture Plain abdominal film / ultrasound / CT renal tract |

| Wounds / soft tissues | Pus / tissue / swabs for culture Re-exploration |

| CNS | CT scan / MRI scan for spine and soft tissues Lumbar puncture |

| Joints | X-ray / ultrasound / CT scan Needle aspiration |

| Sinuses | X-ray / ultrasound / CT scan |

Intra-abdominal sepsis

Intra-abdominal causes of sepsis account for a significant number of cases of unexplained sepsis. Abdominal ultrasound and CT scan are likely to be the most valuable investigation. If pus or abscesses are confirmed, these should be drained and cultured. In the absence of an identifiable cause of sepsis, and in the face of a deteriorating clinical picture, laparotomy may be warranted. Seek senior advice and a surgical opinion. (See Acalculous cholecystitis, p. 176, and Pancreatitis, p. 181.)

Pyrexia of unknown origin

If the cause of sepsis is not apparent, consider investigation for other causes of pyrexia. Pyrexia of unknown origin may be associated with myocardial infarction, autoimmune inflammatory processes (autoantibodies and vasculitic screen), malignancy, drugs and rare infectious diseases. Seek advice.

EMPIRICAL ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY

Table 13.3 provides a guide to empirical antibiotic therapy. You should, however, always follow your hospital antibiotic policy and / or ask advice from your hospital microbiologist.

| Source | Common pathogens | Suggested antibiotic |

|---|---|---|

| Community-acquired pneumonia Including possible atypical pneumonia |

Strep. pneumoniae H. influenzae Staphylococcus aureus Legionella Mycoplasma Chlamydia Coxiella |

Cefuroxime or coamoxiclav (coamoxiclav lower risk of C. difficile in elderly) Cefuroxime or coamoxiclav and clarithromycin |

| Hospital-acquired pneumonia | Strep. pneumoniae H. influenzae Staph. aureus* Enterobacteria |

Early (<5 days) as for community acquired (above) Late (>5 days) piperacillin + tazobac-tam, or ciprofloxacin / ceftazidime / carbapenem |

| Intra-abdominal sepsis | Staphylococci Enterobacteria Anaerobes |

Cefuroxime and metronidazole |

| Pelvic infection | Anaerobes Enterobacteria |

Cefuroxime and metronidazole or carbapenem, plus doxycline |

| Urinary tract | Escherichia coli Proteus species Klebsiella species |

Cefuroxime or gentamicin |

| Wound infection | Staph. aureus* Streptococci Enterobacteria |

Amoxicillin, and flucloxacillin (add metronidazole for traumatic wounds) |

| Necrotizing fascititis | Mixed synergistic flora If group A streptococcus |

Ceftazidime, gentamicin and metronidazole Benzylpenicillin + clin-damycin |

| i.v. line sepsis (remove line) | Staph. aureus* Coag. neg. staph.* Streptococci Enterococci Gram-neg. species Yeasts |

Flucloxacillin and ceftazidime, amphotericin or fungin |

| Meningitis | Neisseria meningitidis Strep. pneumoniae H. influenzae |

Cefotaxime |

* If MRSA or Coag. neg. staph. possible, consider vancomycin or teicoplanin (see below)

SOURCE CONTROL

Wherever possible the source of an infection should be eradicated. If catheter-related sepsis is suspected remove existing arterial and venous lines and send the tips for culture (see Catheter-related sepsis below). Obvious collections of pus should be drained and cultured and potentially infected wounds derided. Ensure appropriate specimens are sent to the lab. Potential means of source control are listed in Table 13.4.

| IV catheter related infection | Remove |

| Chest | Drain pleural collections |

| Abdomen | Drain collections / surgical intervention |

| Soft tissues | Drain and debride infected collections |

| CNS | Drain collections, remove infected shunts |

| Uterus | Remove infected products of conception |

| Urinary tract | Relieve obstruction / drain |

| Joints | Aspirate and wash out |

PROBLEM ORGANISMS

GRAM-POSITIVE ORGANISMS

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

Colonization of skin and wounds with MRSA is increasingly common. Patients are usually isolated in side rooms and barrier nursed to prevent cross-infection. Eradication can be difficult and antibiotic treatment (of colonization) is often pointless. The patient’s flora generally changes over time as their condition improves. If treatment is required, vancomycin, linezolid or teicoplanin are usually the antibiotics of choice. Seek microbiology advice.

Clostridium difficile

This is an anaerobic Gram-positive bacillus that is the main cause of antibiotic-associated ‘pseudomembranous colitis’, following broad-spectrum antibiotics. Presents with profuse diarrhoea (may be blood-stained). Clostridium difficile toxin can be identified in stools. Treatment is with oral (or i.v.) metronidazole or vancomycin. Occasional patients who do not respond to antibiotics may need a colectomy.

Importantly, Clostridium difficile is a spore-forming organism. This means that, unlike many other infections, rapid hand disinfection with alcohol or similar substances is ineffective. Therefore, patients suffering from Clostridium difficile infection should be effectively barrier nursed. Hand washing with soap and water is essential before and after contact with such patients and before contact with subsequent patients. Because of its ease of transmission, all patients who develop Clostridium difficile should be viewed as a potential risk to other patients, and may indeed have developed their own infection as a result of cross-contamination. Rigorous hand washing and infection control measures are vital to prevent cross-infection. (See also p.171.)

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Fungal infection on the ICU is increasingly recognized, particularly among patients who are immune compromised and who have received multiple courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Candida albicans is the most common species. Diagnosis is difficult, but the presence of Candida at more than one site (e.g. oral, genital, wounds) should raise suspicion of systemic candidiasis. Positive blood cultures, or isolation from body cavities or deeper seated infections, e.g. abdominal drains, is diagnostic of systemic candidiasis. Fungi grow poorly in conventional blood culture bottles, and serological markers (e.g. Candida, Aspergillus antigen and antibody tests) may be helpful, although this may not distinguish colonization from infection. Empirical treatment with antifungals may be appropriate. There are a number of conventional and newly introduced agents. Standard treatments include liposomal amphotericin and azoles such as fluconazole. Newer agents include itraconazole caspafungin, micafungin and anidulafungin. Resistance patterns of fungal infection change rapidly. Seek microbiological advice.

CATHETER-RELATED SEPSIS

If there is a strong suspicion of catheter-related sepsis the catheter should be removed and the tip cut off (sterile scissors) and sent for culture. In most cases, the diagnosis is made retrospectively after removal of the suspect catheter, positive tip culture and resolution of the clinical condition.

Ideally there should be a ‘line-free’ interval between removing and replacing catheters but this is often impractical.

Ideally there should be a ‘line-free’ interval between removing and replacing catheters but this is often impractical. If necessary, provided the entry site is not obviously infected, catheters can be changed over a guide wire at the same site. This should only be considered when a clean puncture site is not available or is high risk.

If necessary, provided the entry site is not obviously infected, catheters can be changed over a guide wire at the same site. This should only be considered when a clean puncture site is not available or is high risk.INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS

Clinical vigilance for signs and symptoms of endocarditis is important. The diagnosis should be suspected in any patient with persistent fever, unexplained positive blood cultures (characteristic organisms) and the onset of new or changing heart murmurs. Murmurs may be difficult to detect in a ventilated ICU patient. Other stigmata of endocarditis include Roth spots (retinal haemorrhages), splinter haemorrhages, Osler’s nodes (fingers), and Janeway lesions (palms). Transthoracic echocardiography is useful in patients who have developed valve dysfunction or who have a gross valvular lesion such as regurgitation or incompetence. Smaller valve lesions can however be difficult to detect using transthoracic echo, particularly when the patient is artificially ventilated (poor echo window). Transoesophageal echo (TOE) is the imaging of choice which may identify vegetations or abscess formation around the valves.

MENINGOCOCCAL SEPSIS

Although meningococcal sepsis is more common in paediatric intensive care, occasional cases occur in young adults. It can be a devastating illness resulting in death within a few hours. Always seek senior help.

Management

Give high-flow oxygen by face mask. May require intubation and ventilation. Beware of cardiovascular collapse!

Give high-flow oxygen by face mask. May require intubation and ventilation. Beware of cardiovascular collapse! Establish i.v. access. Give fluids, crystalloid / colloid, to support the circulation. Large volumes are usually required to maintain blood pressure and improve peripheral circulation.

Establish i.v. access. Give fluids, crystalloid / colloid, to support the circulation. Large volumes are usually required to maintain blood pressure and improve peripheral circulation. Establish invasive arterial blood pressure and haemodynamic monitoring CVP / pulmonary artery catheter or alternative.

Establish invasive arterial blood pressure and haemodynamic monitoring CVP / pulmonary artery catheter or alternative. Peripheral and digital ischaemia. If blood pressure is adequate consider epoprostenol (prostacyclin) infusion 5–10 ng kg−1 min−1. This improves microvascular perfusion and may reduce risks of digital ischaemia.

Peripheral and digital ischaemia. If blood pressure is adequate consider epoprostenol (prostacyclin) infusion 5–10 ng kg−1 min−1. This improves microvascular perfusion and may reduce risks of digital ischaemia. Coagulopathy and DIC are common. Send coagulation screen. Avoid giving FFP, platelets and cryoprecipitate unless there is active bleeding as these may increase the tendency to microvascular thrombosis and worsen digital ischaemia.

Coagulopathy and DIC are common. Send coagulation screen. Avoid giving FFP, platelets and cryoprecipitate unless there is active bleeding as these may increase the tendency to microvascular thrombosis and worsen digital ischaemia. Metabolic acidosis is normal. This will improve as the patient’s condition improves. Do not give bicarbonate unless extreme (pH < 7.1) or inotropes ineffective.

Metabolic acidosis is normal. This will improve as the patient’s condition improves. Do not give bicarbonate unless extreme (pH < 7.1) or inotropes ineffective. There is no evidence for the routine use of steroids in meningococcal shock but if adrenal insufficiency is suspected then replacement steroid therapy is appropriate. (This is in contrast to meningococcal meningitis in which recent evidence suggests that steroids may be of benefit. See Meningitis, p. 295.) Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome (adrenal haemorrhage / infarction) is rare and is usually a post-mortem finding.

There is no evidence for the routine use of steroids in meningococcal shock but if adrenal insufficiency is suspected then replacement steroid therapy is appropriate. (This is in contrast to meningococcal meningitis in which recent evidence suggests that steroids may be of benefit. See Meningitis, p. 295.) Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome (adrenal haemorrhage / infarction) is rare and is usually a post-mortem finding.Prophylaxis

Most cases of meningococcal disease are sporadic and ‘outbreaks’ of infection are rare. However, the index patient, direct family contacts and other close contacts require prophylactic treatment with rifampicin (or ciprofloxacin) to abolish nasal carriage of meningococcus. This is organized by the public health department and the case should be reported to them as soon as possible. (See Notifiable infectious diseases below.)

NOTIFIABLE INFECTIOUS DISEASES

In the UK there is a statutory duty to report a number of infectious diseases to the public health services. This is either to enable disease surveillance or because of the broad risk posed to contacts or the public generally. Notifiable infectious diseases are shown in Box 13.3.

| Common | Uncommon |

|---|---|

| Acute encephalitis Food poisoning Leptospirosis Measles Meningitis Meningococcal septicaemia Mumps Ophthalmia neonatorum Rubella Scarlet fever Tetanus Tuberculosis Viral hepatitis Whooping cough |

Acute poliomyelitis Anthrax Cholera Diphtheria Dysentery Malaria Paratyphoid fever Plague Rabies Relapsing fever Smallpox Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Yellow fever Typhoid fever Typhus fever Viral haemorrhagic fever |

The diagnosis of meningococcal sepsis is based on clinical signs. Life-saving antibiotic treatment (cefotaxime or benzylpenicillin) and resuscitation should be commenced immediately on suspicion. This must not be delayed by investigations.

The diagnosis of meningococcal sepsis is based on clinical signs. Life-saving antibiotic treatment (cefotaxime or benzylpenicillin) and resuscitation should be commenced immediately on suspicion. This must not be delayed by investigations.

It is not normally considered necessary for the medical or nursing staff involved in the care of these patients to receive prophylaxis, unless direct contamination has occurred.

It is not normally considered necessary for the medical or nursing staff involved in the care of these patients to receive prophylaxis, unless direct contamination has occurred.