6 Indigestion (chronic epigastric pain or meal-related discomfort)

Case

A 39-year-old female psychologist consults because of problems with indigestion for the past year. She states that after eating a meal she feels very uncomfortable and full. The discomfort she experiences is not at the level of pain, but does interfere with her life. She also feels bloated and is unable to finish normal-sized meals now. She has these symptoms after most meals. She very occasionally will have heartburn (retrosternal burning discomfort in her chest travelling up towards the throat). She never has acid regurgitation and denies dysphagia. She is slightly nauseous at times, but denies vomiting. She has not noticed any change in her bowel habit. Her weight has fluctuated up and down, but overall has been stable. She remembers her mother suffered for years with indigestion problems. She is not taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs supplied ‘over the counter’.

Indigestion and Dyspepsia

The terms ‘indigestion’ and ‘dyspepsia’ mean different things to different people. It is therefore important to clarify with a patient what they mean by indigestion. The term is generally used by patients to describe symptoms related to the upper abdomen or chest. ‘Dyspepsia’ is a term usually used only by medical practitioners, and refers to one or more of the following symptoms: chronic or recurrent epigastric pain, epigastric burning, postprandial fullness or early satiation (inability to finish a normal-sized meal). However, many also include classical symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux (namely heartburn or acid regurgitation) as part of dyspepsia, which has caused confusion; others also include nausea or belching although these symptoms probably have a different pathophysiology (see Ch 1 and Ch 9). The most important underlying causes of dyspepsia are peptic ulcer disease (uncommon), gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (common), cancer (rare) and functional dyspepsia (most common).

Mechanisms Underlying Epigastric Pain

A diverse range of physiological or pathological mechanisms can result in chronic or recurrent epigastric pain. These include (1) inflammation, not only acute, but also chronic; (2) abnormal motor activity producing distension or excessive contraction of hollow organs; (3) hypersensitivity of hollow viscera in the upper gastrointestinal tract; (4) stretching of the capsules of solid viscera, for example the liver; (5) malignant invasion of nerves; and (6) organ-specific responses, such as acid and pepsin acting on nerve fibres in the base of a peptic ulcer. Based on the afferent relays or pathways for pain impulses, activated by these processes, three different types of pain can be appreciated clinically. These types can occur in isolation or together in the one individual. Visceral pain arises from nociceptors situated in the walls of the abdominal viscera, somatic pain from nociceptors situated in the parietal peritoneum and supporting tissues, and referred pain by activation of strong visceral impulses spilling over to the somatic afferent neurones in the same spinal cord segment (Ch 4). Visceral pain tends to be dull, perceived in the midline and poorly localised; it may be described in terms other than ‘pain’, and may be accompanied by symptoms of autonomic disturbance. Somatic pain, like referred pain, tends to be sharp or aching, sustained, lateralised and yet relatively poorly localised; it may be worse on movement. Referred pain tends to be sharp or aching in character, lateral or bilateral and roughly localised to the somatic dermatome. When patients describe pain as superficial, it may arise from lesions in the abdominal wall or hernial sac, but may occasionally also represent referred pain, from disease in intraabdominal or thoracic viscera.

Clinical Assessment

Epigastric pain, which is considered to represent a sense of tissue damage, should be distinguished from discomfort; the latter refers to a subjective, negative feeling that does not reach the qualification or intensity level of pain. Discomfort can include a number of other symptoms including early satiation (inability to finish a normal-sized meal), postprandial fullness and nausea (Ch 9). It is useful to determine the major complaint: whether the symptoms are related to meal ingestion or not, and whether they are intermittent (recurrent or cyclical) or continuous. As with any symptom, the other specific features need to be ascertained, including the site, mode of onset, intensity, character, and precipitating and relieving factors (see Ch 7). For the purposes of this discussion, a duration of 3 months or longer is taken as indicating chronicity, which distinguishes dyspepsia from the acute symptoms present in disorders such as perforated peptic ulcer, acute cholecystitis and acute pancreatitis (Ch 4).

Overlap of dyspepsia with other syndromes

Symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and dyspepsia often overlap. Because of the high specificity of the symptoms of GORD, however, if the patient has predominant or frequent symptoms of heartburn or acid regurgitation, as well as upper abdominal pain/discomfort, the condition should usually be classified as symptomatic GORD, irrespective of the presence or absence of endoscopic oesophagitis (see Ch 1). Likewise, while retrosternal chest pain, and even dysphagia, may be regarded by the patient as indigestion, they should not be classified as dyspepsia. Both cardiac causes (e.g. ischaemic heart disease) and non-cardiac causes (e.g. GORD or oesophageal motility disorders) may be the underlying aetiology in these instances.

Upper abdominal complaints also occur frequently in patients with features compatible with other functional gastrointestinal disorders; irritable bowel syndrome is the commonest of these disorders (see Ch 7). Despite this overlap, approximately two-thirds of patients with dyspepsia and no peptic ulcer or other organic disease report a normal bowel habit, which suggests that they constitute a distinct group from irritable bowel syndrome.

‘Aerophagia’ refers to the repetitive pattern of swallowing air and belching to relieve the sensation of abdominal distension or bloating. It is best regarded as a specific functional gastroduodenal disorder and is considered further in Ch 8.

Differential diagnosis of dyspepsia

The differential diagnosis of dyspepsia is extremely wide, including diseases not only of the gastroduodenum, but also all of the other organs situated in the upper abdomen. Therefore, it is crucial to identify the precise symptoms. Leading questions are often required to elicit the complaints that trouble the patient most. Even when a detailed history has been obtained, the exact clinical diagnosis is often difficult—symptoms such as nocturnal waking, or relief or aggravation by eating often fail to discriminate between the different diagnoses. Patients with dyspepsia can, however, be subdivided into two main categories, based on the known or proposed underlying pathophysiology (Table 6.1). Thus dyspeptic symptoms may be ascribed to:

Table 6.1 Differential diagnosis of epigastric pain or meal-related epigastric discomfort

| Organic | Functional dyspepsia |

|---|---|

Chronic Peptic Ulcer

Chronic peptic ulcer, in most cases, is caused by H. pylori infection (Ch 5) or NSAIDs; an acid hypersecretory state (e.g. the Zollinger-Ellison syndrome due to a gastrin-producing tumour) is a rare but important cause to be aware of in practice.

Gastric cancer

A short history of new onset dyspepsia occurring in a patient over the age of 55 years should raise the suspicion of gastric cancer (Ch 17). Symptoms of pain or discomfort on a daily basis, together with early satiety, increase the probability. Weight loss, anorexia and vomiting are common symptoms, especially when the malignancy is advanced (hence not curable)—these are the alarm features or red flag symptoms. Dysphagia can occur with tumours arising from the cardia or distal oesophagus.

Chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer

Similar symptoms of shorter duration, often with weight loss, may be associated with carcinoma of the pancreas, although this condition can typically present late when the patient is cachectic and jaundiced (Ch 23).

Cholelithiasis

‘Biliary colic’ is associated with the sudden onset of severe or very severe epigastric pain that may pass through or around to the back (Ch 4). Typically there are episodes of pain that occur unpredictably, usually with associated nausea and vomiting. With inflammation of the gall bladder, the pain may shift to the right upper quadrant and become ‘peritoneal’ in type. With biliary colic, movement does not aggravate the pain. The pain is usually not ‘colicky’ but sustained, albeit varying in intensity. Symptoms may be induced by a fatty meal. In the absence of typical biliary pain there appears to be no association between the presence of gallstones in the gall bladder and dyspepsia. If a gallstone enters the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis), there may be associated features of intermittent jaundice, dark urine, pale stools, or with sepsis episodic fever and rigors (see Ch 23).

Other causes

Intestinal ischaemia can sometimes cause dyspepsia. Intestinal or mesenteric angina causes the classical triad of upper abdominal pain induced by eating, a fear of eating (sitophobia), and weight loss (Ch 7).

Metabolic causes such as renal failure, hypercalcaemia or thyroid disease can at times present with dyspepsia. Dyspepsia can occur in patients with longstanding diabetes mellitus who have autonomic neuropathy, gastroparesis or diabetic radiculopathy. Other metabolic causes are discussed in Chapter 7. Referred pain from the chest or back may also occasionally cause chronic upper abdominal pain.

Management of Dyspepsia

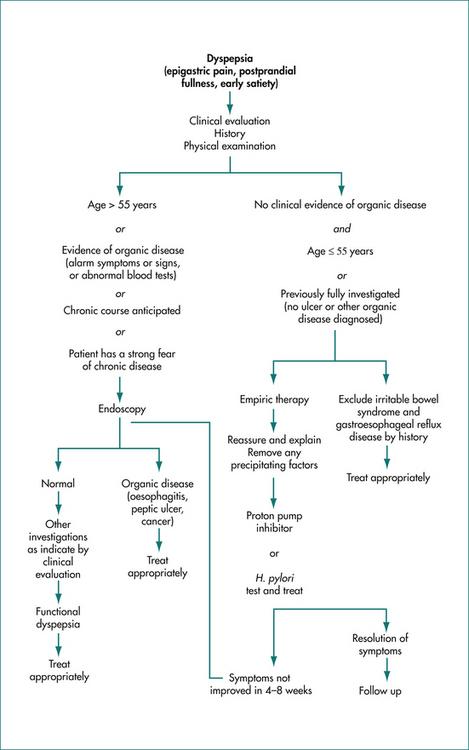

A careful history is important to document the symptoms; in particular gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and biliary disease can in most cases be readily suspected from the history and relevant further investigations and treatment undertaken. Otherwise, if there are no symptoms or signs to indicate a higher probability of organic disease, and the patient is under 55 years of age and is not taking regular aspirin or other NSAIDs, then immediate investigation is not warranted (Fig 6.1).

Empiric therapy

Depending on the age of the patient, and the duration and severity of symptoms, reassurance regarding the low probability of serious disease, and a full explanation of the mechanisms currently believed to underlie the symptoms may be associated with an improvement in symptoms. A short-term empiric trial of a proton pump inhibitor (or an H2-blocker) for 4–8 weeks is the current standard of care, but patients must be followed up. An alternative approach is to test for H. pylori infection (e.g. a urea breath test) and treat positive cases with specific antibiotic therapy (Ch 5). In late middle-age and elderly patients, the threshold for investigation should be much lower, as organic diseases occur more frequently in this age group.

Diseases Associated With Epigastric Pain or Discomfort

Chronic peptic ulcer

Aetiology and pathophysiology

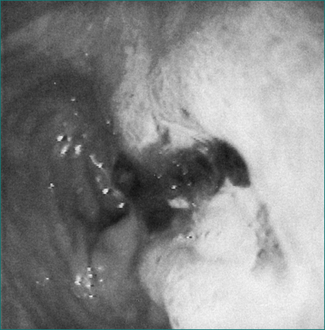

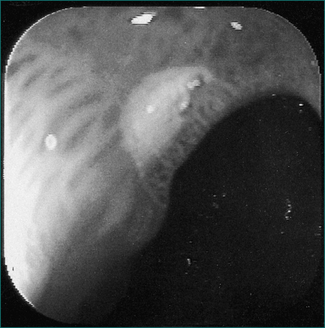

Chronic peptic ulcer can be defined as a break in the mucosa of greater than 5 mm with depth (Figs 6.2 and 6.3). An erosion, on the other hand, is smaller, lacks depth and is not associated with symptoms. In the general population, a chronic ulcer can be demonstrated in about 20% of patients with dyspepsia who are investigated; the risk is higher in the elderly.

H. pylori is a chronic infection of the stomach that causes chronic histological gastritis and most peptic ulcer disease (see Ch 5).

Treatment

All cases of chronic peptic ulceration associated with H. pylori should be treated with combination antibacterial therapy plus antisecretory therapy (Ch 5). Antisecretory therapy is usually then continued for a further 4–6 weeks to ensure ulcer healing although this may not be absolutely necessary. With this type of therapy, successful cure of the infection in over 70% of patients and resolution of the ulcer can be achieved.

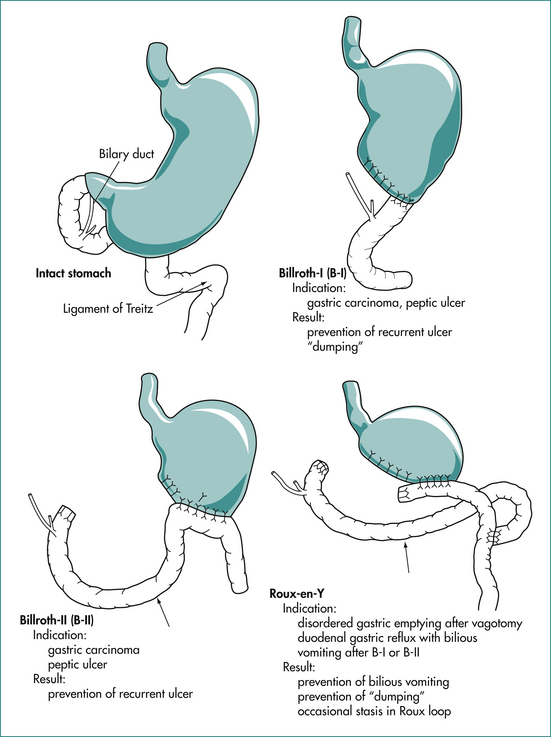

Surgery is now rarely indicated for control of peptic ulcer disease as cure is attainable (Fig 6.4). When surgery is required, the surgery is directed at treating the complication (e.g. oversewing the perforation or under-running the bleeding ulcer). Rarely, a gastric resection will be required if a gastric ulcer is resistant to healing and malignancy cannot be confidently excluded. The ulcer diathesis can be treated by conventional therapy (listed above) after the patient has recovered from the operation. However, many patients in the past underwent gastric surgery for this disease. The complications that may arise in these cases are summarised in Box 6.1.

Box 6.1 Complications of peptic ulcer surgery

Zollinger-Ellison (ZE)/syndrome

The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome refers to a gastrinoma causing gastric acid hypersecretion and, frequently, peptic ulceration. The tumours producing this syndrome may be found in the pancreas (85%) or the duodenal wall. Two-thirds are malignant with metastases. Ulcers in this syndrome may be single or multiple. The increased gastrin may cause gastric hypertrophy with prominent folds. Diarrhoea with or without steatorrhoea occurs in one-third of cases (because the high acid level damages small bowel mucosa, inactivates pancreatic lipase and deconjugates bile salts); in 10% of cases, diarrhoea is the only presenting symptom. The Zollinger-Ellison syndrome can also occur as part of the multiple-endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type I syndrome where there is hyperplasia, adenoma or carcinoma of the pancreatic islets, parathyroid and pituitary. This is an autosomal-dominant condition, so there may be a family history of ulcer. In addition to the clinical features found with a gastrinoma, there is usually hypercalcaemia, secondary to parathyroid disease (Ch 26). Serum gastrin levels should be checked to screen for this diagnosis if patients have multiple or refractory ulcers, enlarged gastric folds or a dilated duodenum, an ulcer plus diarrhoea or steatorrhoea, or hypercalcaemia, associated with ulcer disease. A serum gastrin concentration greater than 1000 μg/mL in patients producing gastric acid (which can be measured by testing the pH of gastric juice at endoscopy or by formal gastric secretory function testing) is virtually diagnostic. Conditions such as pernicious anaemia or postvagotomy surgery can cause a high serum gastrin level, but gastric acid secretion is low. In difficult cases, a secretin test is helpful; gastrinomas cause a paradoxical rise in gastrin in response to a secretin bolus of greater than 100 μg/mL above baseline. Once a diagnosis of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is made, consideration should be given to whether there is evidence of MEN I (e.g. hyperparathyroidism). Thereafter, evidence of metastatic spread (over 60% are malignant) and tumour localisation is sought by a contrast computed tomography (CT) (5 mm sections). Endoscopic ultrasound may identify small tumours. Imaging may miss up to 30% of tumours in this syndrome. Even if no tumour is found by scanning, it can usually be located by surgery.

The tumour should be resected where feasible (liver metastases may also be amenable to resection); otherwise, patients are managed with high dose proton (acid) pump inhibitors to control gastric acid. Approximately 50% of patients who cannot be completely resected die from tumour spread in 10 years; newer chemotherapy regimens may reduce disease progression.

Functional (non-ulcer) dyspepsia

Pathophysiology

Although the pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia remains unknown, a number of physiological factors appear to be associated with the disorder. Most attention has been directed towards assessment of upper gut sensorimotor function.

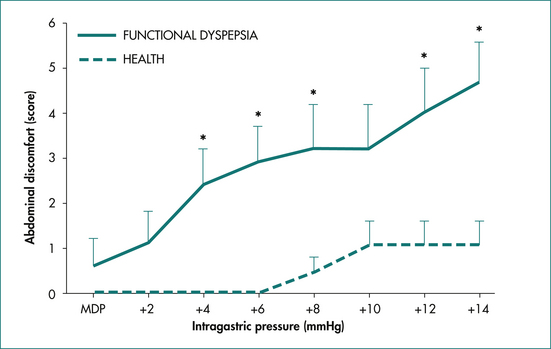

At least some cases of functional dyspepsia appear to be associated with an enhanced gastroduodenal sensitivity to distension (Fig 6.5). The relationship between this phenomenon and the alterations in upper gut motility described above is not clear, but it is likely that in some cases these may be a consequence of altered visceral afferent function. Gastric volumes required to induce feelings of distension and pain have been shown to be significantly lower in patients with functional dyspepsia than in control subjects.

Although acute stress can alter gastrointestinal function and induce symptoms in healthy subjects, the role of life-event stress in the pathogenesis of chronic functional dyspepsia remains controversial. It appears, however, that life events that are highly threatening or which lead to frustration of goals are associated with functional dyspepsia. It is important to note that no characteristic personality profile is demonstrable in patients with functional dyspepsia. Anxiety but not depression is linked to functional dyspepsia. Psychosocial disturbances such as neuroticism, anxiety and depression probably also influence the decision to seek healthcare.

Treatment

The approach to treatment is outlined in Box 6.2 and Figure 6.1.

Box 6.2 Key features of functional dyspepsia

Management

All H. pylori-positive patients with functional dyspepsia may be offered eradication therapy for dyspeptic symptoms, but many will not benefit. Trials with antisecretory drugs, particularly the proton pump inhibitors, have indicated that these medications are modestly superior to placebo in the therapy of functional dyspepsia; patients with epigastric pain may be more likely to respond. Thus, it is reasonable to suggest that these medications should be first-line medications.

Chronic pancreatitis

The most common cause of chronic pancreatitis is alcohol (Box 6.3). Alcohol leads to hypersecretion of a proteinaceous fluid that can precipitate first in the small pancreatic ducts and later in the main pancreatic ducts. These deposits block the ducts and cause dilatation of the ducteals; later, inflammatory infiltrates appear. It is unclear whether or not the normal pancreas secretes a specific protein that inhibits calcium carbonate stone formation (stone-inhibitor protein). Smoking increases the risk of chronic pancreatitis.

Clinical presentation

While patients with chronic pancreatitis may present with episodes of acute pancreatitis (Ch 4), the common mode of presentation is intermittent abdominal pain, usually in the epigastric region after eating (15–30 minutes) and radiating to the back. It may improve by the patient sitting upright and leaning forward. The pain may also occur in the right or left upper quadrant. It is typically severe and is unrelieved by eating or antacids. Alcohol and fatty meals may make the pain worse. It tends to become more continuous with disease progression. There may be diarrhoea and steatorrhoea as well as weight loss due to pancreatic insufficiency (Ch 14). Commonly these patients have a history of high analgesic use and abuse. The clinical problem may be very difficult to evaluate if the patient has become narcotic-dependent. Thus, it may be hard to be sure which of the symptoms are due to chronic pancreatitis.

On physical examination, there may be signs of wasting and malnutrition. Rarely, jaundice is present because of obstruction of the common bile duct. Patients may also have evidence of diabetes mellitus with advanced disease. Other complications of chronic pancreatitis include the development of pseudocysts, which may become infected (Ch 4). Pancreatic ascites can also occur (Ch 20). Clinical evidence of vitamin deficiency is rare (fat-soluble vitamins [A, D, E and K] or B12).

Diagnosis

If patients have diarrhoea or suspected steatorrhoea, a 3-day faecal fat estimation should be obtained. A faecal fat excretion of over 40 g per day is usually only seen with pancreatic steatorrhoea (Ch 14). Cystic fibrosis needs to be considered in children or young adults in such cases and a sweat electrolyte test should be obtained. It is also important to check serum calcium and triglyceride levels to exclude these rare causes of chronic pancreatitis.

Treatment

In difficult cases, relief of pancreatic duct obstruction with endoscopic removal of stones or extracorporeal lithotripsy may sometimes be helpful. Temporary insertion of a stent into a proximally obstructed pancreatic duct may be of value. If a pseudocyst is present in a patient with pain, it may respond to drainage, which can be done radiologically, endoscopically or occasionally by surgery. Coeliac axis nerve blocks are worth a trial, and bilateral thoracoscopic splanchnicectomy has shown promise.

Key Points

Bytzer P. Dyspepsia as an adverse effect of drugs. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24(2):109-120.

Ford A.C., Moayyedi P. Managing dyspepsia. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:288-294.

Kiltz U., Zochling J., Schmidt W.E., et al. Use of NSAIDs and infection with Helicobacter pylori—what does the rheumatologist need to know? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:1342-1347.

Lacy B.E., Cash B.D. A 32-year-old woman with chronic abdominal pain. JAMA. 2008;299:555-565.

Nair R.J., Lawler L., Miller M.R. Chronic pancreatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:1679-1688.

Park D.H., Kim M.H., Chari S.T. Recent advances in autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut. 2009;58:1680-1689.

Talley N.J. Dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1219-1226.

Talley N.J., Choung R.S. Whither dyspepsia? A historical perspective of functional dyspepsia, and concepts of pathogenesis and therapy in 2009. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(suppl 3):S20-S28.

Talley N.J., Seon Choung R. Functional (non-ulcer) dyspepsia and gastroparesis—differentiating these conditions and practical management approaches. Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2009;9:E48-E53.

Talley N.J., Vakil N., Moayyedi P. AGA technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1756-1780.

Talley N.J., Walker M.M., Aro P., et al. Non-ulcer dyspepsia and duodenal eosinophilia: an adult endoscopic population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(10):1175-1183.