Indications for the Boston Keratoprosthesis

Introduction

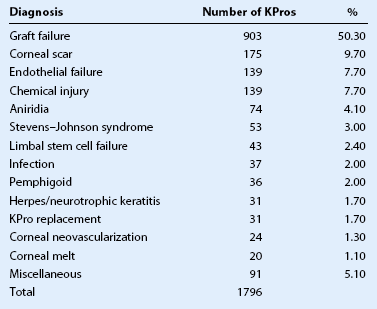

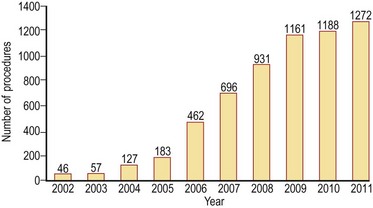

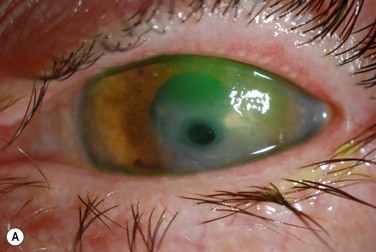

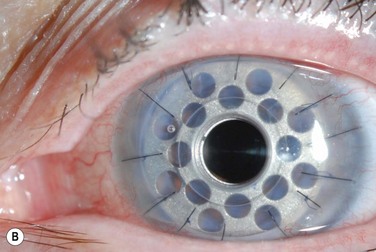

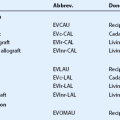

In the past, keratoprosthesis implantation was considered a surgery of last resort, fraught with complications and generally poor outcomes. There has been a dramatic increase in the use of the type I Boston keratoprosthesis (Boston KPro) over the last decade as design modifications to the device itself and changes to the postoperative regimen have improved outcomes and reduced postoperative complications (Fig. 49.1). Graft failure remains the most common indication for the Boston KPro (Table 49.1)1. However, in recent years, the Boston KPro has been used successfully as the primary corneal surgery in conditions in which standard penetrating keratoplasty (PKP) has a poor prognosis, including neurotrophic or vascularized host beds (Fig. 49.2), congenital or acquired limbal stem cell deficiency, autoimmune ocular disorders, and pediatric corneal opacities. Cicatricial and inflammatory autoimmune conditions remain the most challenging KPro cases, and need further advances with immunomodulation and improved biologic materials before the Boston KPro will find widespread acceptance as a treatment for these devastating ocular surface diseases.2

Use of the Boston KPro in Herpetic Keratitis

The 5-year success rate of corneal grafts in patients with herpetic keratitis is significantly less than that in other corneal diseases, such as keratoconus and corneal dystrophies.3 Anesthesia of the host corneal bed, frequent graft rejection episodes, corneal vascularization and poor wound healing all contribute to the suboptimal outcomes of PKP in the setting of herpetic disease.1 In contrast, case reports and small case series suggest the Boston KPro can be successful in patients with herpes simplex or herpes zoster, even in the setting of corneal anesthesia and active inflammation.3–5

The Boston KPro was used in 17 eyes of 14 patients who had repeatedly failed traditional PKP.3 Twelve patients had herpes zoster or herpes simplex as the initial diagnosis, while two patients had keratoconus and developed herpetic keratitis in the corneal graft. Visual acuity improved from light perception to 20/200 preoperatively to 20/25 to 20/70 in 15 of 17 eyes. No complications were reported in 10 patients over a follow-up period that ranged from 7 to 39 months. The remaining patients experienced complications from pre-existing glaucoma or new-onset sterile vitritis.3

The Boston KPro in Congenital Aniridia

The keratopathy associated with congenital aniridia results from corneal epithelial stem cell deficiency and corneal invasion by conjunctival stem cells causing recurrent erosions, chronic pain, corneal ulceration, scarring, and vascularization.6 Treatment with PKP provides short-term visual rehabilitation, but long-term outcomes are poor, due to underlying stem cell deficiency. Keratolimbal allograft can provide visual rehabilitation but requires systemic immunosuppression.7 The Boston KPro offers another option for the visual rehabilitation of aniridic keratopathy and has the advantage of not requiring immunosuppression.

In a retrospective multicenter study of the Boston KPro in aniridia, 14 of 15 patients experienced improved visual acuity from a median of counting fingers to 20/200.6 No KPro extrusions were reported throughout a follow-up period ranging from 2 to 85 months. Preoperative optic nerve and foveal hypoplasia limited the final postoperative vision. Further investigation of the Boston KPro as a standard treatment approach to aniridic keratopathy is underway, and results thus far are encouraging.

Use of the Boston KPro in Children

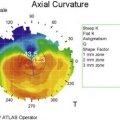

In pediatric PKP, surgically induced astigmatism hinders visual rehabilitation and amblyopia management.1 In addition, the robust immune response in children leads to an increased risk of immunologic rejection and visually significant corneal neovascularization. The Boston KPro provides rapid visual rehabilitation, thus facilitating amblyopia management in children, and has the additional advantage that there is no risk of rejection.

Very few reports of pediatric KPro have been published. Following the initial report of two cases,8 a multicenter case series reported outcomes of 21 Boston KPro procedures in pediatric patients (age 1.5 to 136 mo).9 The most common preoperative diagnoses were failed grafts (55%, mean 3.25 prior grafts) and primary congenital corneal opacity (45%, from Peter anomaly, congenital glaucoma, spontaneous corneal perforations, or dermoid tumor). In patients older than 4 years of age, postoperative visual acuity ranged from counting fingers to 20/30; all infants were able to follow light, fingers, and objects. The Boston KPro was retained in all cases without dislocation, infection or extrusion, although the reported follow-up was limited, ranging from 1 to 37 months with a mean of 9.7 months. Refraction was stable (and without astigmatism) within days of surgery, facilitating amblyopia management. The rapid refractive stability is one of the main theoretic advantages of this device in children.9 Refractive error can be managed by changing the power of the bandage contact lens, thus allowing optimal visual acuity to be maintained as the eye grows. However, some pediatric ophthalmologists have expressed concern that limitation of light exposure to the peripheral retina through the 3-mm aperture of the Boston KPro may have untoward effects, such as progressive high myopia in very young children.

The Boston Keratoprosthesis in Autoimmune Diseases

Patients with ocular autoimmune disorders are typically poor candidates for a traditional PKP, due to concurrent limbal stem cell deficiency and ongoing ocular surface inflammation. Autoimmune diseases, such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome and mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) are well established to have the least favorable prognosis for long-term Boston KPro success.2,10 The high incidence of donor tissue melt and retraction surrounding the central stem of the prosthesis make the use of the Boston KPro in autoimmune eye diseases very challenging, although results have improved over the last 10 years.11 Corneal melting is thought to be due to the heightened inflammatory response intrinsic to the pathogenesis of these diseases. These patients also have a reduced tear film that allows increased microbial activity and proliferation, which may also contribute to ongoing inflammation and subsequent corneal melt.11

In a case series of 15 patients (16 eyes) with SJS who underwent either type I (6 eyes) or type II (10 eyes) Boston KPro surgery, 12 eyes achieved a visual acuity of 20/200 or better after surgery, with eight eyes attaining vision of 20/40 or better. Visual acuity was maintained at 20/200 or better over a mean period of 2.5 years for these 12 eyes. Pre-existing glaucoma was found to be a significant risk factor for visual loss. There were no cases of KPro extrusion or endophthalmitis in this series, which included the addition of topical vancomycin to the postoperative medication regimen.12

The Boston KPro has also been used in other autoimmune diseases, including toxic epidermal necrolysis, MMP, and autoimmune polyendocrinopathy–candidiasis–ectodermal dystrophy.11 Visual acuity can be improved with the Boston KPro, although re-operation is common in patients with underlying autoimmune disease.11 Further understanding of the pathogenesis of corneal melting in these most challenging conditions and advancements in the use of systemic immunomodulators are necessary before widespread use of the Boston KPro in autoimmune ocular surface diseases can be recommended.

Other Indications for the Boston KPro

The Boston KPro has been successfully used following ocular trauma, including chemical, mechanical, and thermal injury. A recent series of 30 trauma patients with preoperative visual acuity ranging from counting fingers to light perception reported postoperative visual acuity ranging from 20/20 to no light perception.13 Postoperative complications, including glaucoma continue to be a challenge, especially following chemical injury.

A recent case report showed short-term anatomical and functional success of the type I Boston Kpro for severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis and Mooren’s ulcer. The keratoprosthesis was retained in both eyes at 1 year postoperatively with a best corrected visual acuity of 20/30 in both patients.14

The Boston KPro can also be used to treat chronic hypotony and corneal opacification.15–17 Dohlman et al.15 reported the initial case of bilateral phthisis secondary to alkali burn with visual acuity improving from LP to 20/60 in both eyes over a 5-month period following Boston KPro implantation. Utine et al.16 reported three monocular patients with chronic hypotony who received a Boston KPro in conjunction with pars plana vitrectomy and silicone oil injection. Functional vision was achieved in two of the three patients. At a follow-up of 11 to 13 months, all three KPros were still in place without retroprosthetic membrane or epithelial defects and with a quiet anterior chamber. A recent retrospective study of patients with silicone oil–induced keratopathy who underwent Boston KPro implantation demonstrated anatomic retention and visual improvement in 7 of 8 eyes.17 The visual acuity improved to 20/200 or better in six eyes, suggesting that eyes that otherwise were likely to fail another corneal graft and eventually progress to phthisis bulbi might be salvaged with some improvement in visual function.

Outcomes of Boston Keratoprosthesis in Ocular Surface Disease compared with Graft Failure

No studies have specifically compared KPro outcomes in patients with ocular surface disease with those done in patients with failed grafts. Zerbe et al.18 in the largest series to date showed a retention rate of 97% in non-cicatrizing graft failure (97 cases) and 89% in chemical burn (19 cases), although the follow-up period of this study was limited. Visual acuity of at least 20/200 was maintained in 90% of the graft failure eyes and in 94% of the chemical injury eyes. A more recent study19 demonstrated more favorable visual outcomes in a small series of type I Boston KPro’s done for limbal stem cell failure (23 eyes) when compared with outcomes in KPro’s done for other indications at all time points of up to 3 years, possibly due to fewer ocular co-morbidities in this group. In addition, KPro retention was better for the limbal stem cell deficient eyes than those done for other conditions, when cases of Stevens–Johnson syndrome were excluded. The most common complication following KPro in the setting of ocular surface disease was persistent epithelial defects in 56% of cases. Corneal melt was also more common (30%), likely secondary to the high rate of persistent epithelial defect. Further work is needed to better characterize the long-term outcomes and complication rates for Boston KPro in ocular surface diseases, but preliminary data suggest that device retention and visual recovery is favorable in non-cicatrizing ocular surface diseases.

References

1. Colby, KA, Koo, EB. Expanding indications for the Boston keratoprosthesis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22:267–273.

2. Yaghouti, F, Nouri, M, Abad, JC, et al. Keratoprosthesis: preoperative prognostic categories. Cornea. 2001;20:19–23.

3. Khan, BF, Harissi-Dagher, M, Pavan-Langston, D, et al. The Boston keratoprosthesis in herpetic keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:745–749.

4. Todani, A, Gupta, P, Colby, K. Type I Boston keratoprosthesis with cataract extraction and intraocular lens placement for visual rehabilitation of herpes zoster ophthalmicus: the “KPro Triple”. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:119.

5. Pavan-Langston, D, Dohlman, CH. Boston keratoprosthesis treatment of herpes zoster neurotrophic keratopathy. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(Suppl. 2):S21–S23.

6. Akpek, EK, Harissi-Dagher, M, Petrarca, R, et al. Outcomes of Boston keratoprosthesis in aniridia: a retrospective multicenter study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:227–231.

7. Biber, JM, Skeens, HM, Neff, KD, et al. The Cincinnati procedure: technique and outcomes of combined living-related conjunctival limbal allografts and keratolimbal allografts in severe ocular surface failure. Cornea. 2011;30:765–771.

8. Botelho, PJ, Congdon, NG, Handa, JT, et al. Keratoprosthesis in high-risk pediatric corneal transplantation: first 2 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1356–1357.

9. Aquavella, JV, Gearinger, MD, Akpek, EK, et al. Pediatric keratoprosthesis. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:989–994.

10. Dohlman, CH, Terada, H. Keratoprosthesis in pemphigoid and Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:1021–1025.

11. Ciralsky, J, Papaliodis, GN, Foster, CS, et al. Keratoprosthesis in autoimmune disease. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2010;18:275–280.

12. Sayegh, RR, Ang, LP, Foster, CS, et al. The Boston keratoprosthesis in Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:438–444.

13. Harissi-Dagher, M, Dohlman, CH. The Boston keratoprosthesis in severe ocular trauma. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43:165–169.

14. Basu, S, Taneja, M, Sangwan, VS. Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis for severe blinding vernal keratoconjunctivitis and Mooren’s ulcer. Int Ophthalmol. 2011;31:219–222.

15. Dohlman, CH, D’Amico, DJ. Can an eye in phthisis be rehabilitated? A case of improved vision with 1-year follow-up. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:123–124.

16. Utine, CA, Gehlbach, PL, Zimmer-Galler, I, et al. Permanent keratoprosthesis combined with pars plana vitrectomy and silicone oil injection for visual rehabilitation of chronic hypotony and corneal opacity. Cornea. 2010;29:1401–1405.

17. Iyer, G, Srinivasan, B, Gupta, J, et al. Boston keratoprosthesis for keratopathy in eyes with retained silicone oil: a new indication. Cornea. 2011;30:1083–1087.

18. Zerbe, BL, Belin, MW, Ciolino, JB. Results from the multicenter Boston Type 1 Keratoprosthesis Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1779 e1-e7.

19. Sejpal, K, Yu, F, Aldave, AJ. The Boston keratoprosthesis in the management of corneal limbal stem cell deficiency. Cornea. 2011;30:1187–1194.