Indications and Techniques

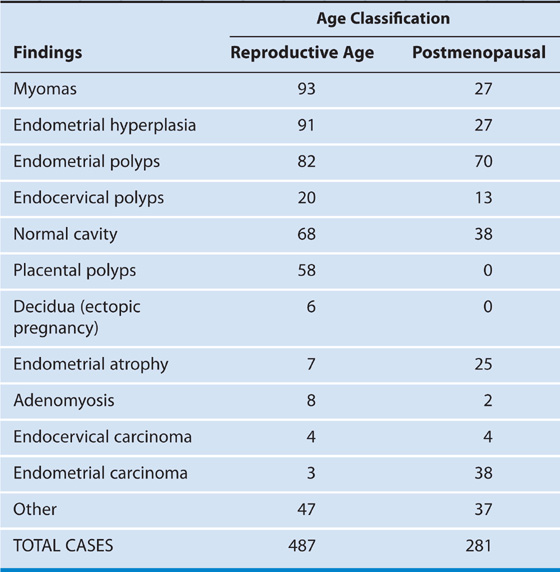

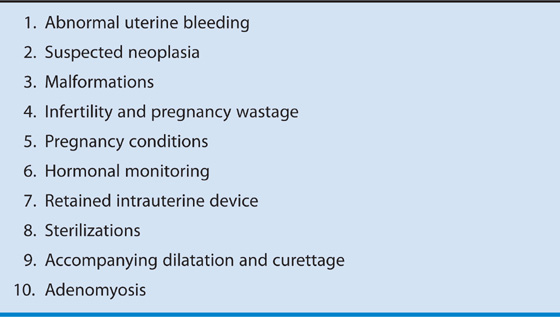

Operative hysteroscopy is performed for the treatment of organic disease with one exception. That exception is the operation of endometrial ablation, which is done to treat abnormal uterine bleeding in the absence of organic disease (e.g., endometrial hyperplasia or cancer). Table 107–1 lists the most frequent indications for hysteroscopy and Table 107–2 for abnormal uterine bleeding by age-related diagnosis.

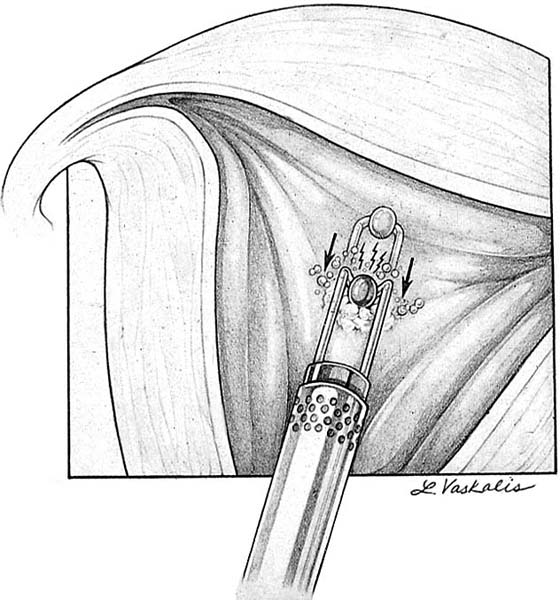

Certain principles prevail for all hysteroscopic surgery. In Chapter 103, the quantification of medium intake and outflow was already mentioned. No hysteroscopic surgery should be performed in an unclear visual field. The best example of the latter is one in which the bleeding is so brisk that it discolors the flushing medium, creating a pink or red field of view. No energy device should be activated on the forward thrust movement of an electrosurgical or laser-energized tool. Power should be applied only during the return stroke, that is, when the device is moving away from the uterine fundus (Fig. 107–1).

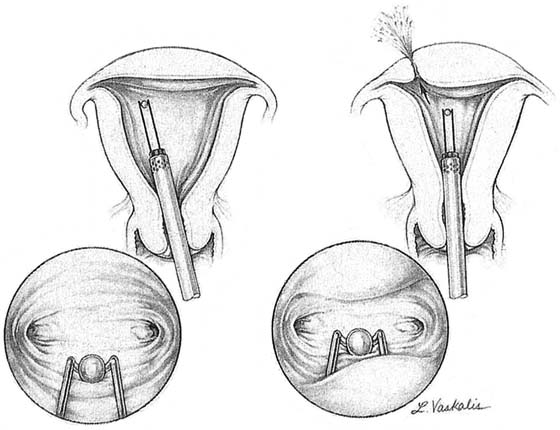

Another dictum involves loss of uterine distention and cessation of the surgical procedure. Loss of distention translates into a diminished view of the operative field. A cause for the loss of distention must be identified. Perforation of the uterus must be the first thing ruled out (Fig. 107–2).

Dilation of the cervix is typically required for the insertion of an operative sheath as compared with a diagnostic sheath (Fig. 107–3). The diagnostic sheath’s diameter does not exceed 5 mm, whereas the average operative sheath measures 8 mm. The surgeon must never overdilate the cervix because the fluid medium will leak out retrograde, resulting in the inability to properly distend the uterine cavity.

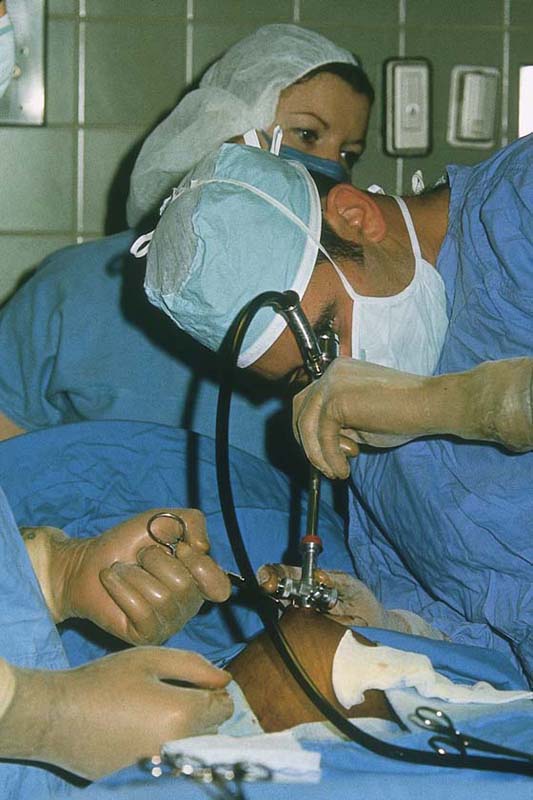

Certain procedures require simultaneous laparoscopy to avoid or immediately diagnose uterine perforation (Fig. 107–4). These include large submucous myoma resection and uterine septum section. Difficult cases of intrauterine adhesiolysis may benefit by viewing the uterus from above.

Clearly, proper preparation of the patient preoperatively will facilitate the performance of surgery. Evaluation of the endometrial cavity by endometrial sampling is required before an ablative operation is performed to rule out cancer. Administration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) is advised before a myomectomy or an endometrial ablation is performed. A septum should be preferentially cut during the proliferative phase of the cycle.

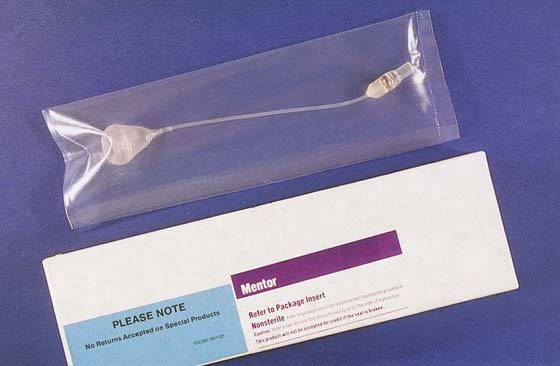

The gynecologist who undertakes to perform operative hysteroscopy must be prepared to manage bleeding from the operative site. Coagulation via energy devices may be used; however, when these methods fail, an intrauterine balloon should be placed into the uterine cavity (Fig. 107–5). Typing and holding blood beforehand is suggested to anticipate possible emergency transfusion for hemorrhage.

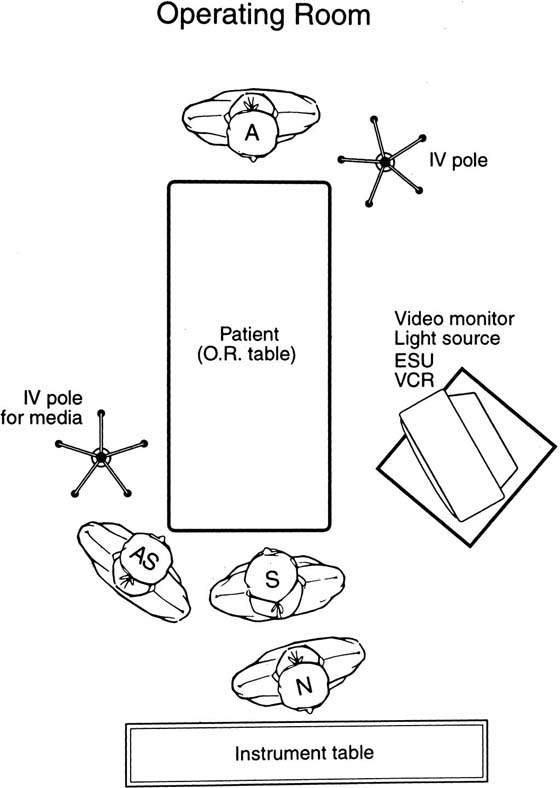

Finally, the orientation of nursing personnel, equipment, patient, anesthesiologist, and surgeon is key to a well-organized operating theater and subsequently the safe, expeditious utilization of operative time (Fig. 107–6).

FIGURE 107–1 During electrosurgery or laser surgery, the energy source is not activated while the electrode or the fiber is advanced. Power is applied only as the ball electrode (in this case) is retracted toward the sheath.

FIGURE 107–2 All surgery should stop when uterine distention is lost. The figure and inset on the left illustrate the resectoscope within a properly distended cavity. On the right, a perforation has occurred and the cavity is collapsing around the resectoscope.

FIGURE 107–3 Dilation, when required, should be performed with Pratt dilators because they are tapered and gentler on the cervix. Dilation always creates some bleeding within the uterus. Overdilation results in retrograde leakage of the hysteroscopic medium and loss of uterine distention. In fact, departure of the medium may force the hysteroscopy to be cancelled.

FIGURE 107–4 Laparoscopy is an important adjunct to hysteroscopy, especially to prevent or at least recognize perforation. The uterus should be elevated via the hysteroscope from time to time to allow the laparoscopist to examine the posterior and fundal portions of the uterus.

FIGURE 107–5 If bleeding occurs after completion of operative hysteroscopy, an intrauterine balloon is inserted and inflated initially to 3 cm3. For a normal-sized cavity, the balloon inflation volume should be limited to 5 cm3. The balloon stem is pulled sharply down to close off the uterine canal at the level of the internal os. A vacuum bag is attached to the catheter to record blood loss.

FIGURE 107–6 This schematic drawing illustrates the arrangement of personnel in the operating room for operative hysteroscopy.

Indications

Indications

Hysteroscopic Findings in 768 Patients With Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Hysteroscopic Findings in 768 Patients With Abnormal Uterine Bleeding