CHAPTER 35 Indications and Contraindications

Just as with hip and knee arthroplasty, as the volume of shoulder arthroplasties performed each year increases, so will the number of patients requiring revision shoulder arthroplasty. Indications for performing revision shoulder arthroplasty are variable and numerous and can include problems related to the glenoid, problems related to the humerus, and problems related to the soft tissues (rotator cuff, instability). Rarely, infection, either early postoperative or late-appearing hematogenous, is an indication for revision arthroplasty. Complications related to healing of the greater and lesser tuberosities can be observed after unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty performed for proximal humeral fractures. Finally, certain periprosthetic humeral fractures are an indication for revision shoulder arthroplasty. This chapter details our specific indications and contraindications for revision shoulder arthroplasty.

PROBLEMS RELATED TO THE GLENOID

Glenoid Erosion

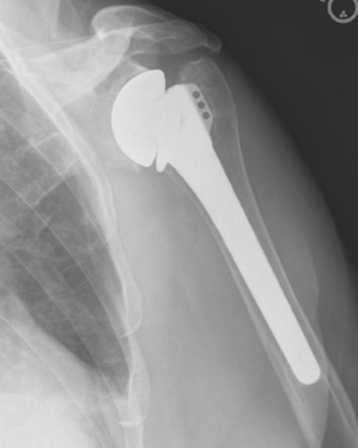

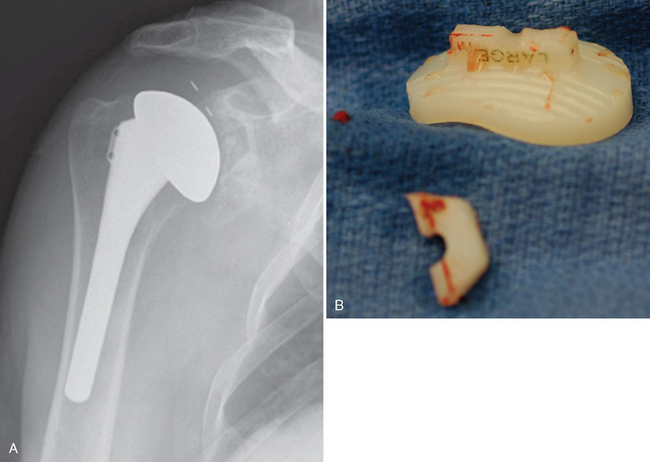

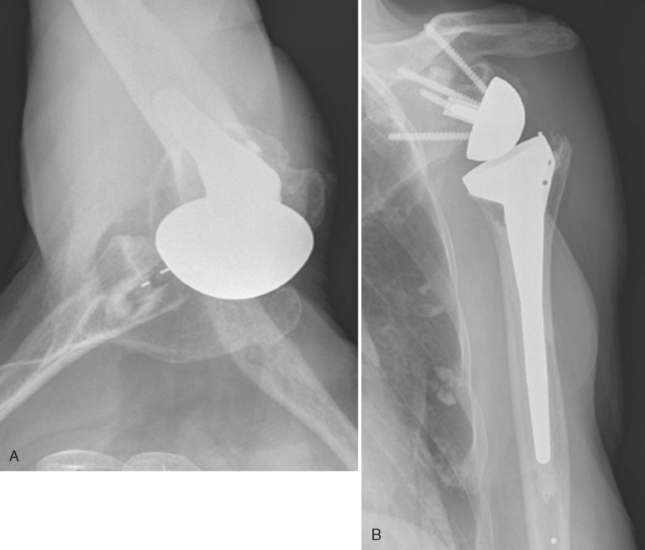

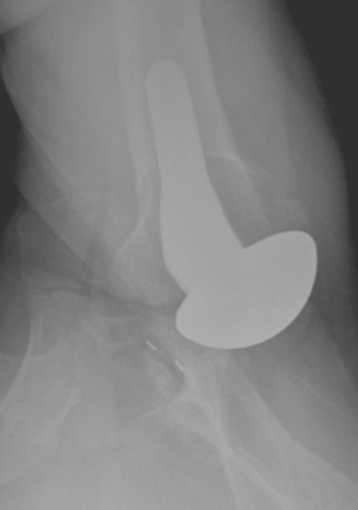

Glenoid erosion after hemiarthroplasty is a multifactorial problem.1 It may occur early or late and does not seem to be related to any readily identifiable risk factor. This problem occurs when the metallic prosthetic humeral head erodes into the softer glenoid bone (Fig. 35-1). Initially, pain may be the sole manifestation of this problem. As the erosion progresses medially, the normal length-tension relationships of the rotator cuff may become compromised and result in substantial weakness (Fig. 35-2).

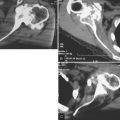

Glenoid erosion may be central or peripheral. If the rotator cuff is intact, as in primary osteoarthritis, the erosion is usually central or, less commonly, posterior (Fig. 35-3). If the rotator cuff is deficient, the erosion is generally superior (Fig. 35-4) or, less commonly, anterior (if the subscapularis is deficient; Fig. 35-5).

Figure 35-3 Computed tomogram demonstrating central glenoid erosion after hemiarthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis.

Figure 35-4 Superior glenoid erosion in a patient who has undergone hemiarthroplasty for rotator cuff tear arthropathy.

Glenoid erosion is best treated by resurfacing of the glenoid if sufficient native glenoid bone is available for implantation of a glenoid component (see Chapter 36). Frequently, the humeral component will require revision for glenoid exposure, and two options are available to the surgeon. We may exchange the component for a smaller head size in an unconstrained arthroplasty (Fig. 35-6) or change to a reverse-design arthroplasty. In general, with a functioning rotator cuff, an unconstrained arthroplasty is performed for revision arthroplasty. If rotator cuff function is significantly compromised, revision to a reverse prosthesis is performed.

Glenoid Component Failure

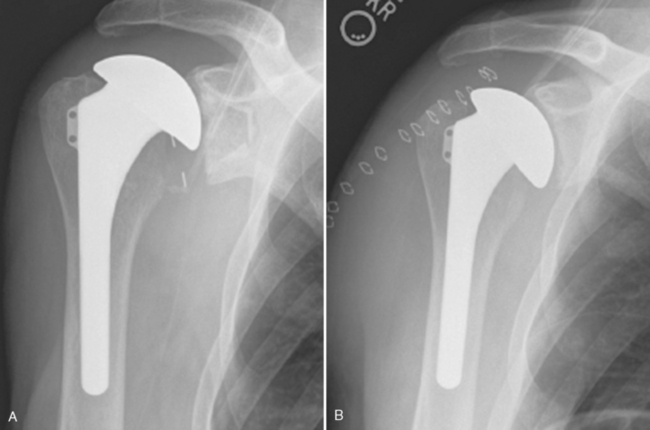

Glenoid component failure can vary from subtle loosening to migration of the component with severe glenoid bone loss (Fig. 35-7). Additionally, mechanical failure of the implant can necessitate revision surgery (Fig. 35-8). When considering revision surgery for failure of a glenoid component, the surgeon must first decide whether to simply remove the failed glenoid component or to remove the failed glenoid component and reconstruct the osseous glenoid. In debilitated patients seeking mainly pain relief without significant concern for function, isolated removal of the glenoid component is usually the best treatment option. In other patients, glenoid reconstruction with iliac crest bone graft is indicated. For patients undergoing revision with an unconstrained prosthesis, we reconstruct the glenoid with an iliac crest bone graft as the first stage. Six months later, after complete incorporation of the bone graft, if the shoulder is still painful, we perform the second stage, which consists of placement of a new glenoid component (Fig. 35-9). When performing revision surgery with a reverse-design prosthesis, glenoid reconstruction and revision can often be performed as a single stage, provided that the central post of the revision glenoid component can be firmly seated in native glenoid bone (Fig. 35-10).

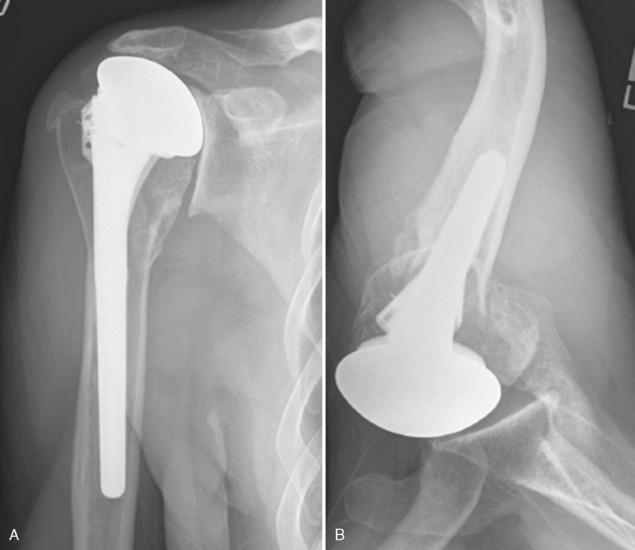

Reverse Glenoid Component

In our experience, failure of the glenoid component of a reverse prosthesis is less common than failure of the glenoid component of an unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty. The most common problem that we observe is inadvertent placement of the glenoid component in a superiorly oriented position (Fig. 35-11). This usually occurs when a superior surgical approach has been used to place the reverse prosthesis. Although this radiographic finding does not merit revision surgery in and of itself, revision is indicated if this problem evolves into early glenoid loosening (Fig. 35-12).

Figure 35-11 Superiorly oriented glenoid component after reverse shoulder arthroplasty performed through a superior approach.

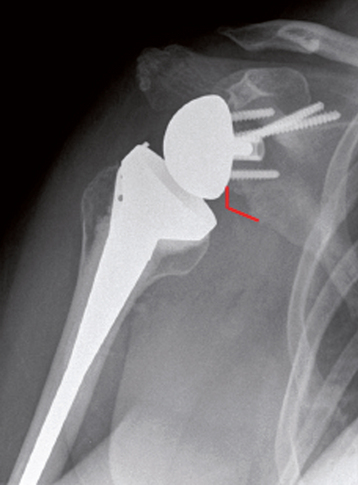

Another radiographic finding related to a reverse glenoid component is inferior scapular notching. This finding can be related to excessive superior placement of the reverse glenoid component (Fig. 35-13). Notching, even when it is severe, has not been shown to cause loosening of the glenoid component, and revision surgery is unnecessary in the absence of glenoid loosening.

PROBLEMS RELATED TO THE HUMERUS

Unconstrained Humeral Components

The main problem that leads us to revise an unconstrained humeral component is placement of a humeral head prosthesis that is too large (Fig. 35-14). This can lead to stiffness, glenoid problems, and rotator cuff problems. If the stem of the humeral implant is acceptably positioned, the humeral head is simply exchanged for a smaller size.

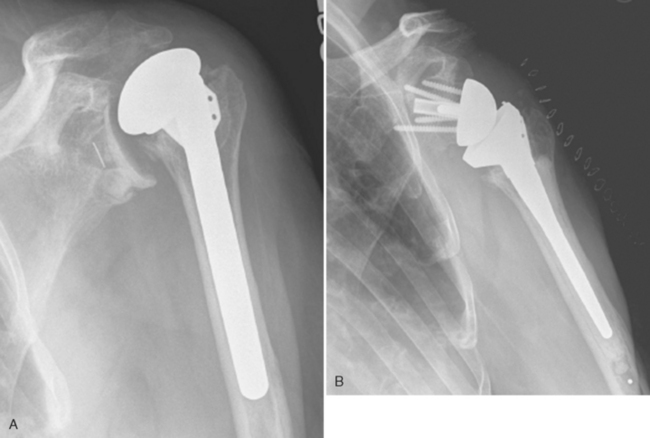

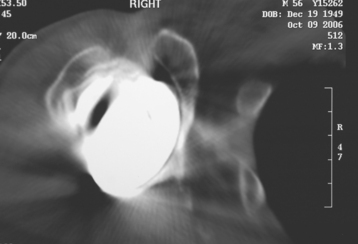

Reverse Humeral Components

Even in cases in which a reverse humeral component is properly positioned, the deltoid muscle can “stretch out” and result in loss of prosthetic stability and, ultimately, dislocation. Patients most at risk for this complication are those with proximal humeral bone loss (Fig. 35-15). In such cases it is sometimes necessary to add more length to the humeral component to restore prosthetic stability via restoration of deltoid tension. This can usually be accomplished by exchanging the primarily placed polyethylene liner for a thicker liner or adding a metallic augment, or both (Fig. 35-16). Tensioning the deltoid by adding length to the prosthesis almost never requires removal of the humeral stem. In cases in which use of a metallic augment and the thickest polyethylene liner fails to stabilize the prosthesis, multiple metallic augments can be stacked together and secured with a custom-manufactured screw (Fig. 35-17).

Figure 35-15 Patient with severe proximal humeral bone loss resulting in dislocation of the reverse prosthesis.

PROBLEMS RELATED TO SOFT TISSUE

Subscapularis Problems

If subscapularis insufficiency is coupled with either dynamic or static anterior instability after unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty, our experience has been that revision to a reverse-design prosthesis is the only reliable way of restoring glenohumeral stability (Fig. 35-18).

Other Rotator Cuff Problems

The development of rotator cuff insufficiency after unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty is very rare. In cases in which a patient has sustained a massive (two or more tendons) rotator cuff tear after unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty that has resulted in severe dysfunction and static or dynamic glenohumeral prosthetic instability, revision to a reverse-design prosthesis can be considered (Fig. 35-19).

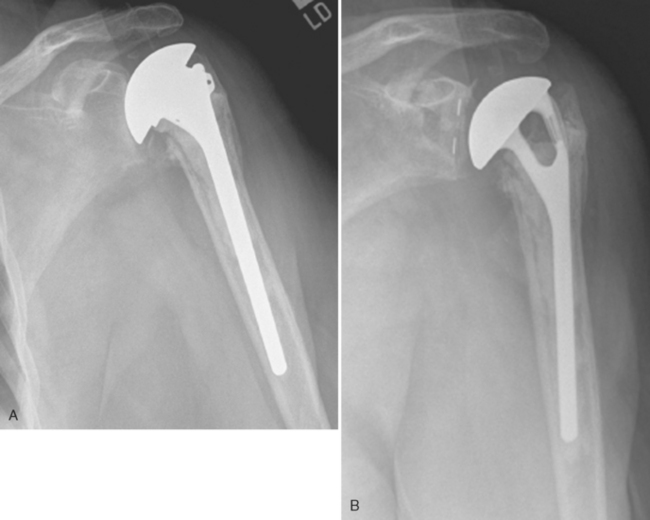

Instability

Glenohumeral instability after unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty usually occurs in one of two scenarios. First, instability can occur with rotator cuff insufficiency, as previously mentioned. Second, instability can occur in patients who have undergone unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis with posterior glenoid wear and posterior capsular distention (Fig. 35-20). In these cases we have found soft tissue procedures unpredictable in restoration of glenohumeral stability. We opt for revision to a reverse-design prosthesis (Fig. 35-21).

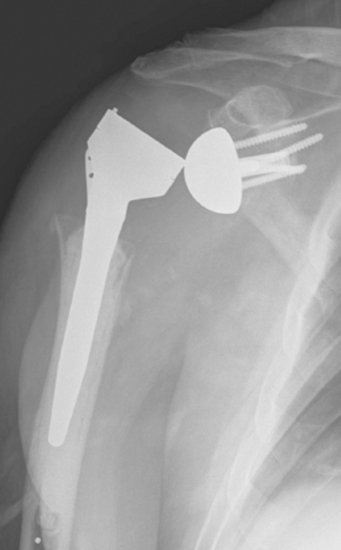

Figure 35-21 Revision of a posteriorly dislocated unconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty to a reverse prosthesis.

A less common problem causing instability is an unconstrained humeral implant positioned in incorrect version (Fig. 35-22). This is an indication for revision of the humeral component and placement of the revision component in correct humeral version.

INFECTION

Fortunately, infections are rare after shoulder arthroplasty. When infections do occur, surgery is indicated. Early postoperative infections (<2 weeks after surgery) can be treated initially with multiple irrigation and débridement sessions, exchange of any nonfixed modular components (i.e., humeral head), and retention of the remainder of the components. Late infections and early infections failing component-retaining procedures should be treated with component removal. Revision arthroplasty can be considered as a second stage after appropriate treatment of the infection (Fig. 35-23).

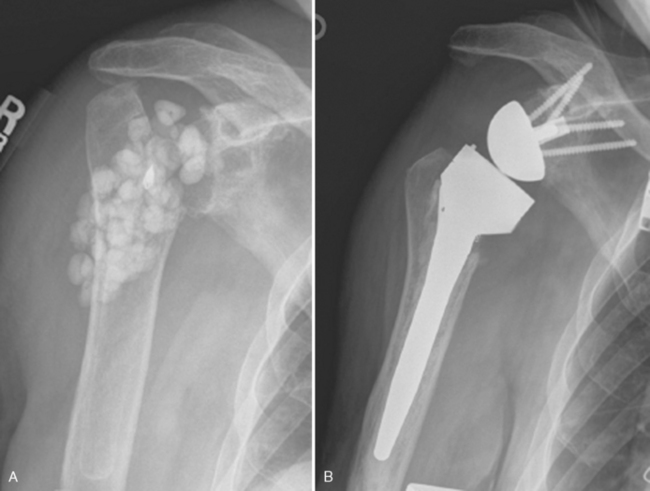

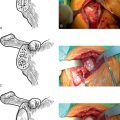

SPECIAL SITUATION—TUBEROSITY PROBLEMS AFTER UNCONSTRAINED ARTHROPLASTY FOR FRACTURE

Tuberosity malunion and nonunion after unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fracture are an indication for revision shoulder arthroplasty with a reverse-design prosthesis (Fig. 35-24). Our experience in achieving reliable tuberosity union once tuberosity migration has occurred has not been favorable.

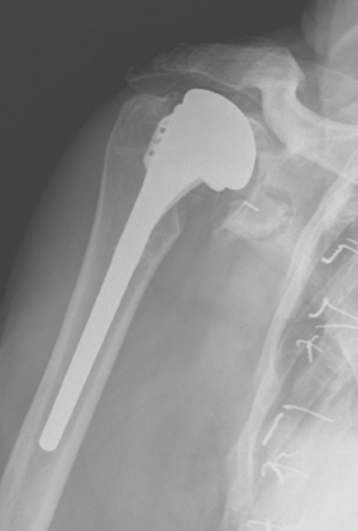

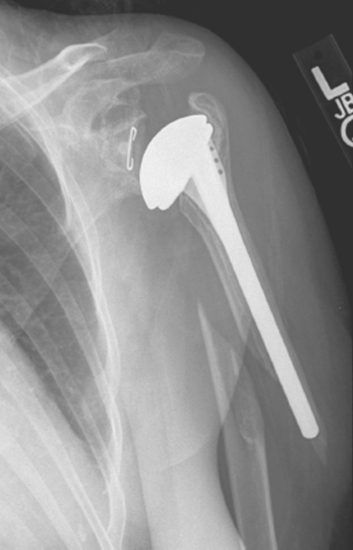

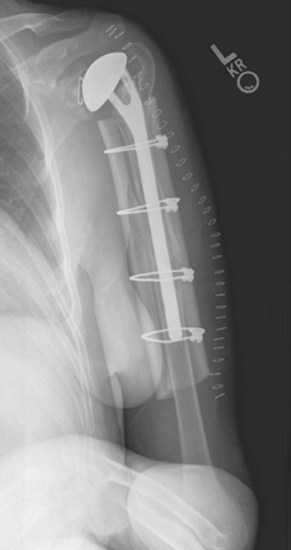

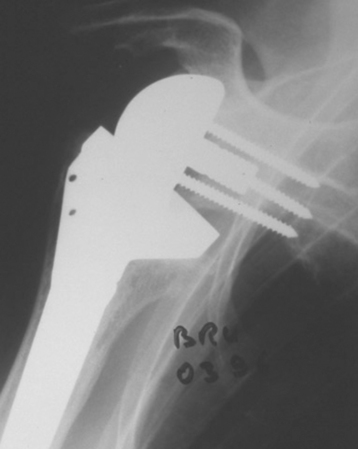

PERIPROSTHETIC FRACTURE

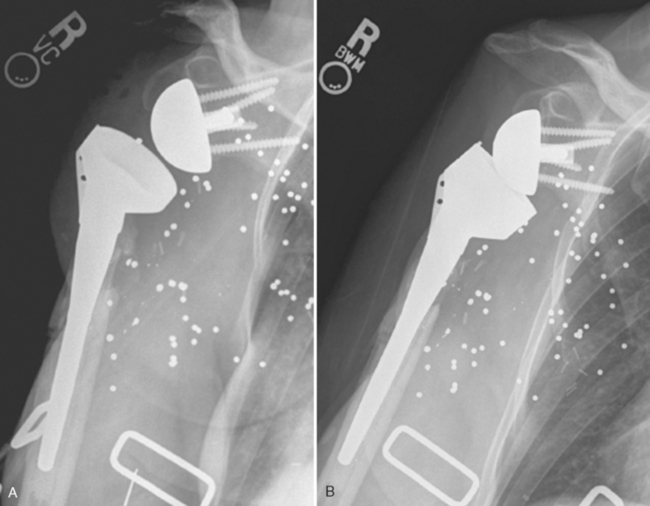

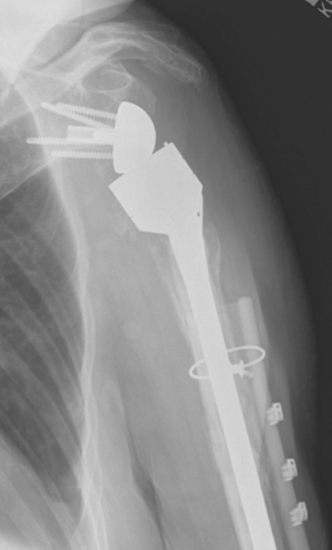

Displaced periprosthetic fractures not amenable to nonoperative treatment or treatment by open reduction and internal fixation because of inability to achieve adequate fixation proximally are an indication for revision shoulder arthroplasty (Fig. 35-25). In this scenario, we believe it best to remove the existing humeral stem and revise to a long-stem humeral component to act as an intramedullary fixation device. This is combined with allograft struts placed peripherally at the fracture site and fixated with cerclage cables (Fig. 35-26). In addition to this scenario, any periprosthetic fracture in which the humeral stem is loose is an indication for revision of the humeral component via the same technique.

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO REVISION SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY

Contraindications to revision shoulder arthroplasty are listed in Table 35-1. Some of these contraindications are absolute, whereas others are relative.

Table 35-1 CONTRAINDICATIONS TO REVISION SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY

| Contraindication | Absolute or Relative | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Poor generalized health | Relative | Appropriate perioperative medical treatment required |

| Active infection | Absolute | Must clear infection first. May be candidate for revision as a second stage |

| Axillary nerve palsy | Absolute | Better suited for resection arthroplasty |

| Deltoid insufficiency | Absolute | Better suited for resection arthroplasty |

| Insufficient humeral bone stock | Relative | May be able to restore bone stock with a proximal humeral reconstruction |

| Insufficient glenoid bone stock | Relative | May be able to restore bone stock with a staged procedure |

| Poor patient motivation | Absolute |