CHAPTER 6 Indications and Contraindications

Indications for unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty can be divided into arthroplasty performed for acute fracture and arthroplasty performed for chronic shoulder disease. This chapter focuses on indications for unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty in patients with chronic shoulder disease. Indications for unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty in patients with an acute fracture are covered in Chapter 17.

HEMIARTHROPLASTY VERSUS TOTAL SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY: INDICATIONS FOR GLENOID RESURFACING

Two major requirements exist for performance of glenoid resurfacing in unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty: the glenoid bone must be sufficient to allow implantation of components (judged by preoperative imaging studies; see Chapter 7), and the anterior and posterior rotator cuff must be functioning (judged by clinical examination and preoperative imaging studies; see Chapter 7).1 Lack of either of these requirements represents an absolute contraindication to glenoid resurfacing. A relative contraindication to glenoid resurfacing is young patient age. A “safe” age at which to implant a polyethylene glenoid component has not been established. Concerns of polyethylene wear are heightened in younger patients because of their residual life expectancy. In general, we favor biologic glenoid resurfacing in patients younger than 40 years in whom total shoulder arthroplasty would otherwise be indicated.

PRIMARY OSTEOARTHRITIS

Primary osteoarthritis was initially described by Neer and is the most common single indication for shoulder arthroplasty in our practice.2 In a large multicenter study, primary osteoarthritis was the underlying cause in half of the primary shoulder arthroplasties performed.3

Clinical Findings

Clinical findings in patients with primary osteoarthritis include glenohumeral crepitus and stiffness. Rota-tor cuff testing may be normal or compromised by pain.

Imaging Findings

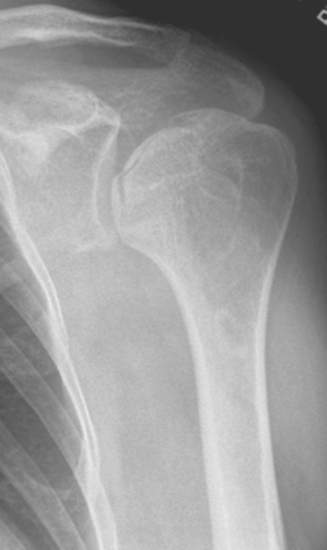

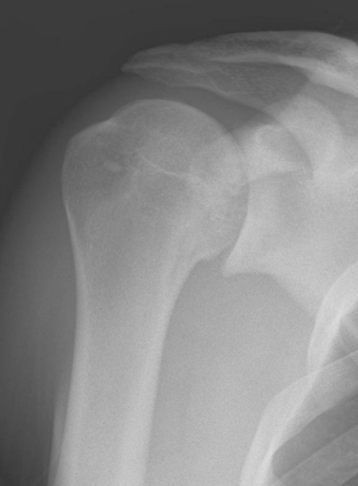

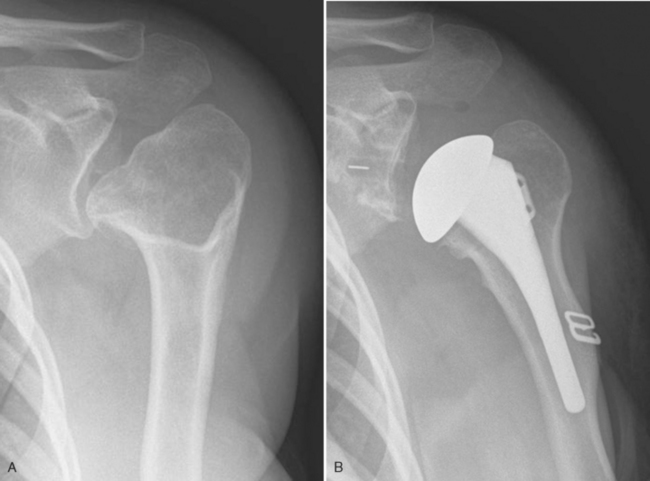

Plain radiography demonstrates loss of the normal glenohumeral joint space. Humeral head osteophytes are usually present and may be large (Fig. 6-1). Loose bodies may be apparent on plain radiography, especially in the subscapularis recess (Fig. 6-2).

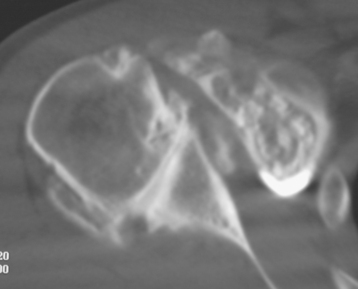

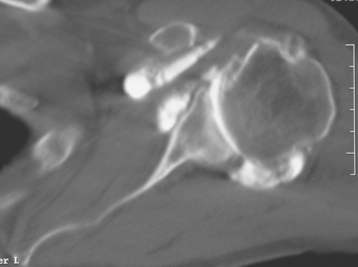

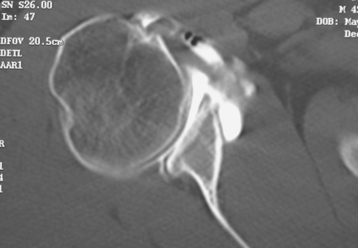

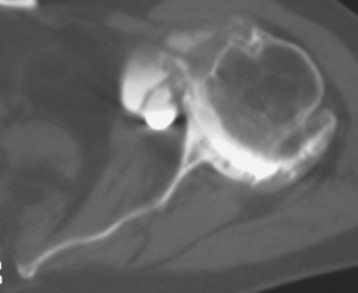

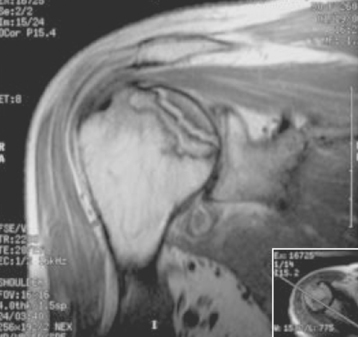

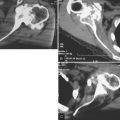

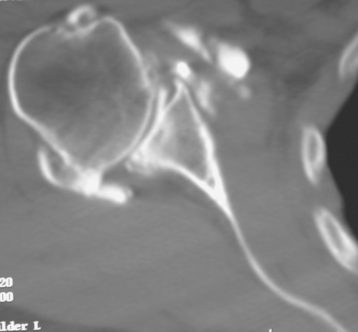

Secondary imaging studies (computed tomographic arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging) will show the “classic” posterior glenoid erosion with biconcavity in only 20% of cases (Fig. 6-3).3 Approximately half of patients with primary osteoarthritis will have the humeral head centered within the glenoid, and another 25% will demonstrate posterior subluxation without osseous erosion (Fig. 6-4).3 Less than 5% of patients with primary osteoarthritis will demonstrate a dysplastic-appearing glenoid morphology(Fig. 6-5).3

Figure 6-3 Computed tomography demonstrating the “classic” biconcave glenoid seen in primary osteoarthritis.

Seven percent of patients with primary osteoarthritis have a full-thickness rotator cuff tear limited to the supraspinatus, and an additional 7% have a partial-thickness rotator cuff tear.4 Moreover, moderate to severe fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus or subscapularis (or both) occurs in approximately 20% of patients with primary osteoarthritis.4

Special Considerations

We perform total shoulder arthroplasty in nearly all cases of primary osteoarthritis because it has been shown to be superior to hemiarthroplasty without an increased risk of complications or reoperations.5,6 The only patients with primary osteoarthritis in whom we perform hemiarthroplasty are those with insufficient glenoid bone or anterior or posterior rotator cuff insufficiency. In patients with rotator cuff insufficiency, we usually opt for a reverse-design prosthesis instead of a hemiarthroplasty (see Section Four).

RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common inflammatory joint disease. Shoulder manifestations develop in 60% to 90% of patients as their disease progresses. In a large multicenter study, rheumatoid arthritis was the underlying cause in 12% of the primary shoulder arthroplasties performed.7

Imaging Findings

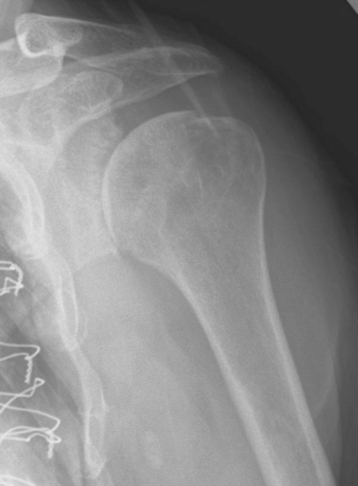

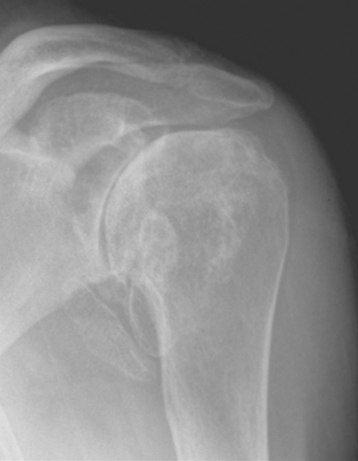

Plain radiography demonstrates loss of the normal glenohumeral joint space. Humeral head osteophytes are rarely present (Fig. 6-6). The humeral head may be centered or statically migrated, depending on the condition of the rotator cuff.

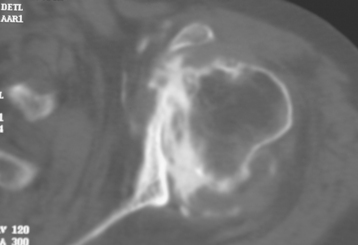

Secondary imaging studies (computed tomographic arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging) may show protrusio-type glenoid morphology (Fig. 6-7). Eight percent of patients with rheumatoid arthritis have a full-thickness rotator cuff tear limited to the supraspinatus, and an additional 9% have a partial-thickness supraspinatus tear.8 Twelve percent of patients with rheumatoid arthritis have massive rotator cuff tears involving the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons.8 Additionally, moderate to severe fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus or the subscapularis (or both) occurs in approximately 45% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.8

Special Considerations

We perform total shoulder arthroplasty in nearly all cases of rheumatoid arthritis because it has been shown to be superior to hemiarthroplasty.9 The only patients with rheumatoid arthritis in whom we perform hemiarthroplasty are those with insufficient glenoid bone or anterior or posterior rotator cuff insufficiency. In patients with rotator cuff insufficiency, we usually opt for a reverse-design prosthesis instead of a hemiarthroplasty, provided the patient does not have severe osteopenia (see Section Four).

HUMERAL HEAD OSTEONECROSIS

Although humeral head osteonecrosis is rare, it is the most common nontraumatic indication for shoulder hemiarthroplasty in our practice. In a large multicenter study, osteonecrosis was the underlying cause in only 5% of the primary shoulder arthroplasties performed.10 Many factors have been implicated as contributing to atraumatic osteonecrosis, including corticosteroid use, alcohol abuse, and hematologic disorders. Despite the influence of these factors, most cases of humeral head osteonecrosis are idiopathic.

Imaging Findings

Radiographic classification of humeral head osteonecrosis has evolved from that described for the femoral head.11,12 Stage I is a preradiographic stage that requires diagnosis by magnetic resonance imaging or scintigraphy. Stage II is characterized by a zone of osteopenia surrounding a zone of relatively increased osseous density with the sphericity of the humeral head preserved (Fig. 6-8). Stage III is characterized by the presence of a subchondral fracture (the “crescent sign”); sphericity of the humeral head is preserved (Fig. 6-9). Stage IV corresponds to loss of sphericity of the humeral head as a result of collapse of the necrotic segment (Fig. 6-10). Stage V is characterized by loss of glenoid articular cartilage with secondary osteoarthritis (Fig. 6-11). Stage VI is characterized by osseous collapse of the humeral head with medialization of the humerus relative to the glenoid (Fig. 6-12).

Figure 6-11 Stage V osteonecrosis is characterized by loss of glenoid articular cartilage with secondary osteoarthritis.

Magnetic resonance imaging will reliably show the area of osteonecrosis in all except the earliest cases (what has been described as stage 0 in the hip and characterized by increased intraosseous pressure without imaging abnormalities), as shown in Figure 6-13. Secondary imaging studies (computed tomographic arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging) almost always show a concentric glenoid.

The incidence of rotator cuff tears in patients with atraumatic osteonecrosis is similar to that observed in primary osteoarthritis. Conversely, moderate to severe fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus or subscapularis (or both) occurs less frequently than with primary osteoarthritis.10

Special Considerations

We perform hemiarthroplasty for stage I, II, III, and IV osteonecrosis because the results have been shown to be equal to those of total shoulder arthroplasty.12 In patients with stage V and VI osteonecrosis, we perform total shoulder arthroplasty if no contraindications to glenoid resurfacing exist.

INSTABILITY ARTHROPATHY

Instability arthropathy of the shoulder necessitating shoulder arthroplasty is a rare entity; it is seen in less than 5% of unconstrained primary shoulder arthroplasties in our practice. Patients with previous shoulder dislocations treated operatively and nonoperatively are included in this category. Patients usually fall into a bimodal distribution with regard to age at the time of initial dislocation. The first group of patients dislocate their shoulder when they are relatively young, and progressive arthropathy develops over a period of several years. The second group of patients are older (>60 years) at the time of initial dislocation and are prone to a rapidly developing glenohumeral arthritis that may result in a complete loss of articular cartilage within months of the initial dislocation. We have not been able to distinguish between what has previously been termed “capsulorrhaphy arthropathy” and “instability arthropathy” and consequently include these patients in a single entity under the diagnosis of instability arthropathy.13

Imaging Findings

Plain radiography demonstrates loss of the normal glenohumeral joint space. In patients with slowly progressing arthropathy, the radiographic changes are very similar to those of primary osteoarthritis and consist of humeral head osteophytes with or without loose bodies (Fig. 6-14). In older patients with rapidly appearing instability arthropathy, loss of the glenohumeral joint space with a paucity of osteophytes is apparent (Fig. 6-15).

Secondary imaging studies (computed tomographic arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging) show posterior subluxation with or without glenoid erosion with biconcavity in 20% of cases, and this finding occurs in both patients who have previously undergone stabilization surgery and those who have not.13 Twenty percent of patients with instability arthropathy have a full-thickness rotator cuff tear, with most being limited to the supraspinatus tendon.13

Special Considerations

We perform total shoulder arthroplasty in nearly all cases of instability arthropathy because it has been shown to be superior to hemiarthroplasty and is not associated with an increased risk of complications or reoperations.13 The only patients with instability arthropathy in whom we perform hemiarthroplasty are those with insufficient glenoid bone or anterior or posterior rotator cuff insufficiency. In patients with rotator cuff insufficiency, we usually opt for a reverse-design prosthesis instead of hemiarthroplasty (see Section Four).

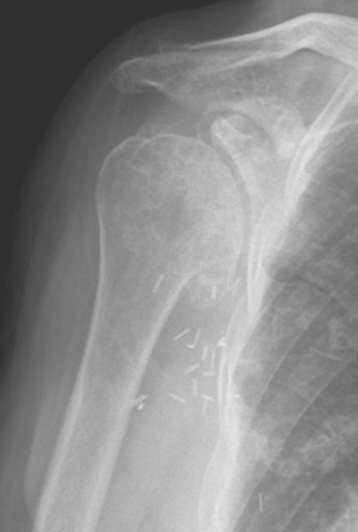

POST-TRAUMATIC ARTHRITIS

Post-traumatic glenohumeral arthritis covers a large spectrum of causes, including chondral damage secondary to blunt trauma and malunion and nonunion of the proximal humerus after fracture. This diagnosis can be relatively uncomplicated to treat when little glenohumeral osseous deformity is present (Fig. 6-16) or extremely difficult to treat in the case of severe proximal humeral malunion (Fig. 6-17). The integrity of the rotator cuff and the position of the tuberosities are very important when considering a patient for shoulder arthroplasty. If the rotator cuff is largely intact and the tuberosities are acceptably positioned to allow nearly normal rotator cuff function, unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty is our treatment of choice. In situations in which rotator cuff or tuberosity compromise (nonunion, severe malunion) is severe and would require a greater tuberosity osteotomy, we often opt for a reverse-design prosthesis (see Section Four).

Rarely, post-traumatic arthritis will develop after a glenoid fracture (Fig. 6-18). In these cases it is of paramount importance to ensure that the osseous glenoid is sufficient to allow placement of a glenoid component (Fig. 6-19). We prefer computed tomo-graphic arthrography rather than magnetic resonance imaging.

Imaging Findings

Secondary imaging studies (computed tomographic arthrography, magnetic resonance imaging), like plain radiography, show variable findings, depending on the deformity present. We much prefer the use of computed tomographic arthrography over magnetic resonance imaging in this diagnosis for the osseous detail provided.

Special Considerations

We perform total shoulder arthroplasty in nearly all cases of post-traumatic arthritis because it has been shown to be superior to hemiarthroplasty without an increased risk of complications or reoperations.14 The only patients with post-traumatic arthritis in whom we perform hemiarthroplasty are those with insufficient glenoid bone or anterior or posterior rotator cuff insufficiency. In patients with rotator cuff insufficiency or in those who would require a greater tuberosity osteotomy to perform humeral arthroplasty, we usually opt for a reverse-design prosthesis instead of hemiarthroplasty (see Section Four).

FIXED GLENOHUMERAL DISLOCATION

A distinct subset of patients with glenohumeral instability are those with fixed (chronic) glenohumeral dislocations (Fig. 6-20). These dislocations can be anterior or posterior. Long-standing dislocations can result in severe glenohumeral arthritis with complete loss of proximal humeral articular cartilage, especially in older patients. Our results using unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty in this subset of patients have been disappointing.15 We now use a reverse-design prosthesis in this patient subset (see Section Four).

ROTATOR CUFF TEAR ARTHROPATHY (GLENOHUMERAL OSTEOARTHRITIS WITH A MASSIVE ROTATOR CUFF TEAR)

Historically, hemiarthroplasty has been the operative treatment of choice in patients with osteoarthritis combined with a massive irreparable rotator cuff tear (Fig. 6-21). Unconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty is contraindicated because of the risk of loosening of the glenoid component by eccentric loading of the glenoid component.1 The results of hemiarthroplasty for this diagnosis, however, have been disappointing, with most patients achieving only modest improvement postoperatively.16

Since its introduction in the United States and because of its superior results, we have used the reverse prosthesis in nearly all cases of osteoarthritis with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears that we have treated operatively.16 We still consider the use of unconstrained hemiarthroplasty in patients with insufficient glenoid bone stock to support the reverse-prosthesis glenoid component and in elderly patients with severe osteopenia who would seemingly be at increased risk for glenoid failure after the implantation of a reverse-design prosthesis (Fig. 6-22).

POSTINFECTIOUS ARTHROPATHY

Postinfectious arthropathy is a rare and somewhat controversial indication for shoulder arthroplasty. Successful shoulder arthroplasty in these patients depends on complete eradication of the infection before shoulder arthroplasty is undertaken. We use a systematic approach in our workup of these patients preoperatively. We first confirm through review of previous medical records the type of infection (hematogenous versus postoperative, type of organism). We also ensure that the infection was properly and adequately treated. Consultation with an infectious disease specialist is obtained and continued throughout the preoperative workup and the shoulder arthroplasty. Patients are not considered for shoulder arthroplasty for postinfectious arthropathy until they are free of infection for at least 6 months.

Imaging Findings

Plain radiography demonstrates loss of the normal glenohumeral joint space in nearly all cases (Fig. 6-23). Humeral head osteophytes may be present if the condition has been long-standing and has progressed over many years. The humeral head may be statically subluxated superiorly or anterosuperiorly in cases of massive rotator cuff tearing (Fig. 6-24).

Special Considerations

Patients are not considered for arthroplasty until 6 months after their shoulder infection has resolved, and the preoperative infection workup is not initiated until this time. In all patients with postinfectious arthropathy, fluoroscopically guided aspiration of the glenohumeral joint is performed after the patient has been off all antibiotics for at least 2 weeks (even antibiotics used for other conditions such as respiratory infections). The aspirate is cultured for aerobic bacteria, anaerobic bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi. Serum studies include a complete blood count with differential, a sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. At the time of fluoroscopically guided aspiration, patients undergo computed tomographic arthrography or magnetic resonance imaging (if they are allergic to radiographic contrast material).

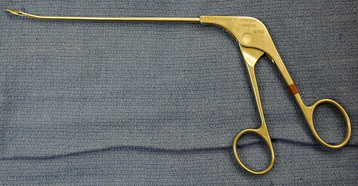

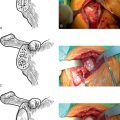

In all patients with postinfectious arthropathy and negative aspirate cultures, arthroscopic synovial biopsy is performed before arthroplasty. An arthroscopic punch is used to obtain more than 10 synovial specimens before the administration of perioperative antibiotics (Fig. 6-25); after obtaining the synovial specimens, standard perioperative intravenous antibiotics are administered immediately. These specimens are sent for microscopic analysis by a pathologist and cultured for aerobic bacteria, anaerobic bac-teria, mycobacteria, and fungi. If these cultures are positive or if findings of the frozen section are indicative of infection (more than five polymorphonuclear leukocytes per high-power field on five consecutive fields), the patient is considered actively infected and treated as such, and the arthroplasty is delayed in-definitely.17 If this workup is negative for infection, the patient is a candidate for total shoulder arthroplasty. With these criteria our infection rate has been no higher for this indication than for primary osteoarthritis.

GLENOHUMERAL CHONDROLYSIS

A rare but disturbing disease process that we are seeing with increasing frequency is glenohumeral chondrolysis.18 We have observed this diagnosis in patients in the early portion of their third decade. Nearly all patients have a history of an arthroscopic shoulder stabilization procedure, with or without the use of thermal energy.18 We have observed a single patient with glenohumeral chondrolysis at age 21 after a single dislocation with no surgery performed. The chondrolysis that occurs is diffuse and affects both the humeral head and glenoid.

Imaging Findings

Plain radiography demonstrates loss of the normal glenohumeral joint space. Humeral head osteophytes are absent (Fig. 6-26).

GLENOHUMERAL ARTHRITIS ASSOCIATED WITH NEUROLOGIC PATHOLOGY

Infrequently, we encounter patients with glenohumeral osteoarthritis combined with a systemic neurologic disorder. The most common neurologic disorder in patients with glenohumeral arthritis is Parkinson’s disease.19 Clinically, these patients are usually functioning at a lower level than patients with primary osteoarthritis. Radiographically and on secondary imaging studies, these patients resemble those with primary osteoarthritis (Fig. 6-27).

GLENOHUMERAL ARTHRITIS ASSOCIATED WITH PREVIOUS RADIATION THERAPY

An indication for shoulder arthroplasty that we are seeing less frequently is glenohumeral arthritis after radiation therapy (Fig. 6-28).20 Most patients in this diagnostic group have undergone radiation therapy for the treatment of breast cancer or lymphoma. Radiographically, some cases resemble aseptic osteonecrosis and other cases resemble inflammatory arthropathy. This indication is becoming less common as radiotherapy technology improves and becomes less toxic.

GLENOHUMERAL ARTHRITIS ASSOCIATED WITH SKELETAL DYSPLASIA

An exceedingly rare indication for unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty is glenohumeral arthritis associated with skeletal dysplasia. Little is known about this entity. Our limited experience with this indication has led us to treat it like primary osteoarthritis (i.e., perform total shoulder arthroplasty), provided that the anterior and posterior rotator cuff is intact and the osseous glenoid is sufficient. Many of these patients require custom-manufactured implants because of their small size and osseous distortion (Fig. 6-29).

TUMOR

Tumors about the shoulder girdle are an exceptionally rare indication for unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty. In our practice, we infrequently assist in reconstruction of the shoulder after tumor resection by an orthopedic oncologic surgeon. If the resection leaves the rotator cuff and tuberosities intact and attached to the humeral diaphysis, an unconstrained prosthesis can be considered and would usually consist of a hemiarthroplasty. In nearly all cases of shoulder girdleTable 3-1 tumor, however, the rotator cuffis substantially compromised by the resection. In our practice, we opt for use of a reverse-design prosthesis (see Section Four).

CONTRAINDICATIONS TO UNCONSTRAINED SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY

Contraindications to unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty are listed in Table 6-1. Some of these contraindications are absolute and others are relative. Additionally some situations are contraindications to glenoid resurfacing with an unconstrained implant but not to unconstrained hemiarthroplasty.

Table 6-1 CONTRAINDICATIONS TO UNCONSTRAINED SHOULDER ARTHROPLASTY

| Contraindication | Absolute or Relative | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Poor generalized health | Relative | Appropriate perioperative medical treatment required |

| Active infection | Absolute | |

| Axillary nerve palsy | Relative | Probably better suited for resection arthroplasty or arthrodesis |

| Suprascapular nerve palsy | Relative | Glenoid component contraindicated; better suited for hemiarthroplasty or a reverse prosthesis |

| Massive rotator cuff tear | Relative | Glenoid component contraindicated; better suited for hemiarthroplasty or a reverse prosthesis |

| Insufficient humeral bone stock | Absolute | |

| Insufficient glenoid bone stock | Relative | Glenoid component contraindicated; better suited for hemiarthroplasty |

| Ankylosed shoulder | Absolute | |

| Previous shoulder arthrodesis | Absolute | |

| Upper motor neuron lesion | Relative | Absolute contraindication if the patient has uncontrolled shoulder spasticity |

| Poor patient motivation | Absolute |

1 Franklin JL, Barrett WP, Jackins SE, Matsen FAIII. Glenoid loosening in total shoulder arthroplasty: Association with rotator cuff deficiency. J Arthroplasty. 1988;3:39-46.

2 Neer CS2nd. Replacement arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:1-13.

3 Edwards TB. Primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: Epidemiological, clinical, and radiographic findings in patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:65-72.

4 Edwards TB, Boulahia A, Kempf JF, et al. The influence of the rotator cuff on the results of shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: Results of a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:2240-2248.

5 Edwards TB, Kadakia NR, Boulahia A, et al. A comparison of hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: Results of a multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:207-213.

6 Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, Hammerman SM. Shoulder arthroplasty with or without resurfacing of the glenoid in patients who have osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:26-34.

7 Aswad R, Franceschi JP, Levigne C. Rheumatoid arthritis: Epidemiology and preoperative radiographic assessment. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:159-162.

8 Vandermaren C, Docquier P. Shoulder arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis: Influence of the rotator cuff on the results. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:177-182.

9 Loehr J, Levigne C. Shoulder arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis: Influence of the glenoid on the results. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:171-176.

10 Willems WJ. Atraumatic avascular osteonecrosis of the humeral head: Epidemiology and radiology. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:121-126.

11 Cruess RL. Steroid-induced avascular necrosis of the head of the humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58:313-317.

12 Nové-Josserand L, Basso M. Prosthèses d’épaule sur ostéonécroses avasculaires: Facteurs pronostiques. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:135-142.

13 Matsoukis J, Tabib W, Guiffault P, et al. Shoulder arthroplasty in patients with a prior anterior shoulder dislocation: Results of a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1417-1424.

14 Duparc F, Trojani C, Boileau P. Results of shoulder arthroplasty in cephalic collapse or necrosis following proximal humerus fractures (type 1 fracture sequelae). In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:279-289.

15 Matsoukis J, Tabib W, Guiffault P, et al. Primary unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty in patients with a fixed anterior glenohumeral dislocation: Results of a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:547-552.

16 Favard L, Lautmann S, Sirveaux F, et al. Hemiarthroplasty versus reverse shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of osteoarthritis with massive rotator cuff tear. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:261-268.

17 Feldman DS, Lonner JH, Desai P, Zuckerman JD. The role of intraoperative frozen sections in revision total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1807-1813.

18 Larsen MW, Higgins LD, Basamania CJ: Severe glenohumeral chondrolysis following shoulder arthroscopy: A series of 6 cases treated with hemiarthroplasty. Paper presented at the 22nd Open Meeting of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons, March 2006, Chicago.

19 Garreau de Loubresse C. Prothèse d’épaule et affections neurologiques. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:195-203.

20 Godenèche A. Shoulder arthroplasty and previous radiotherapy. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Molé D, editors. 2000 Prosthèses d’Epaule … Recul de 2 à 10 Ans. Paris: Sauramps Medical; 2001:143-148.