23 Independent learning

In Chapters 21 and 22 we looked at how students learn in the lecture and small group settings. Independent learning by students outside these contexts has always been a feature of education. The importance of independent learning, where students take charge of their learning and tailor it to their own particular needs, has become increasingly recognised.

The importance of independent learning

There are a variety of reasons for the increased interest in independent learning:

• There has been a move from teacher-centred learning, where the emphasis is on what the teacher teaches, to student-centred learning with the emphasis on what the student learns.

• The excessive use of lectures as a learning experience has been criticised and more time is available in the curriculum for other learning activities.

• Curricula now include electives or options where, for part of the course, students plan their own studies as described in Chapter 17.

• Collaborative learning and peer-to-peer learning is increasingly becoming part of mainstream education as discussed in Chapter 27.

The benefits of independent learning

Independent learning offers a number of advantages:

• With a more diverse student population now admitted to medical school, the learning can be matched to the needs of the individual student.

• The move to an outcome-based model (see Section 2) has made it easier for students to understand what is expected of them and makes it possible for them to create their own personal learning programme. When asked about the necessity of attending lectures students indicate that the main reason is to learn what they should be studying. In outcome-based education the learning outcomes are transparent.

• There is an increasing focus on distance learning and hybrid models that incorporate face-to-face and distance learning. Independent learning by the student is a key feature.

• Students now learn in a variety of sites such as the community, the district hospital and clinical skills centres. This often results in the students having to take more responsibility for their own learning.

• The need for life-long learning and continuing professional development is recognised. This requires students to learn to take more responsibility for their own learning early in their training and to acquire and refine the necessary learning skills.

• Advances in technology and internet developments have resulted in rich and powerful learning experiences becoming available.

• If independent learning is used to replace some lectures, the teacher is free to engage in more rewarding activities interacting with small groups or individual students.

Benefits for the student

• Choose to work at their own pace spending whatever time is necessary to achieve the required mastery of the subject.

• Decide when and where they study. This may be in the work place, on the job or at home.

• Tailor the content of the learning to their personal learning needs.

• Select the method of learning and an instructional design to match how they best learn. Some students are visual learners while others prefer the audio channel.

• Engage to a greater extent in deep learning and reflect on the subject as they pursue their studies.

• Monitor their own progress, using appropriate learning resources, and adjust their continuing learning based on feedback received.

Role of independent learning in the curriculum

Two questions have to be asked about the role of independent learning in the curriculum. First, how much time should be scheduled in the curriculum for independent learning or private study? Some curricula have formal activities timetabled from 9.00am until 5.00pm leaving the student free for independent study only at other times. This is built on the premise that if time is left for private study students will not make full use of the opportunity and teachers will not be employed in the work for which they have been engaged. A second decision relates to the extent to which the students’ independent learning should be managed or the control left with the students. There are strong arguments for replacing the term ‘self-directed learning’ with the term ‘directed self learning’ as all students benefit from some direction or management of their learning. The need for this will vary from student to student, and with the same student in the different phases of undergraduate and postgraduate education. It has been suggested that the level of autonomy given to a student is one of the most important decisions a teacher has to make. Too little direction will result in confusion and inefficient and ineffective learning. Excessive direction will be de-motivating and even result in boredom. This is described in Chapter 13.

The role of the teacher

• Creating a supportive learning environment for students that encourages independent learning, self-confidence, curiosity and the desire to continue to learn. Independent learning will be fostered by a climate that is flexible and responsive to the learner’s needs.

• Briefing students on the role of independent learning in the curriculum and, if students are relatively inexperienced, providing counselling and advice on the skills required.

• Working with the students to help them develop their own learning plan.

• Communicating the core learning outcomes expected of the student.

• Assisting students to identify appropriate learning resource materials and providing advice on how they can best be used. The teacher may also create new learning materials or annotate or adapt existing resources.

• Advising and assisting students to monitor their progress and assess their mastery of the subject.

• Responding to problems that may arise and being available, perhaps at a specified time and place, to advise students.

Learning resources

A wide range of learning resources are available to support independent learning. These include:

• Published books and journal articles. Print has the advantage that it does not require technology. It is highly portable, and the text can be easily annotated or highlighted.

• DVDs. These have the advantage of offering multi-media images including video clips of procedures or personal commentaries from the author.

• Online resources. An increasing amount of learning material is available for instant access through a range of websites including YouTube, Wikipedia and Facebook. There may be a problem however with quality assurance.

• Recordings and podcasts of lectures.

• Resources delivered through smart phones and other mobile devices such as the iPad.

• Tele- and web-conferences using a tool such as Wimba. These allow live interaction with other students and with a teacher or facilitator.

• Models and simulators as discussed in Chapter 25.

• Patients, both real and simulated, as discussed in Chapter 25.

A teacher may wish to create independent learning resources for use by his or her students. Unless these are simply recordings of their teaching sessions, which is not advised, it can be a demanding task and is best undertaken in collaboration with an educational technologist or a colleague who has experience in the technology and in instructional design. The same general educational principles apply that were described in Chapter 2. Feedback should be provided, learning should be active rather than passive, and the students encouraged to reflect on what they have learned. Students should be able to individualise the resources to meet their own personal needs and the content should be relevant and matched to the specified learning outcomes.

Independent learning and the curriculum

Independent learning can be scheduled in the curriculum:

• As a replacement for scheduled activities such as lectures. It may be used as a substitute for lectures when a new course is planned or to replace lectures in an existing course to free students’ time for other activities.

• As an alternative option to student attendance at a lecture. Podcasts are available for this purpose in many medical schools. Students have the choice of attending the lecture or covering the topic at a time and place more convenient to them.

• As an adjunct to existing learning opportunities. The modern equivalent of the reading list includes URLs for online resources and other multi-media. The teacher can provide annotations and comments to assist the student to select the most appropriate resources.

Study guides

The concept of study guides to support a student’s learning was introduced in Chapter 13. They can play an important part in independent learning. The student is guided through the range of learning opportunities and given advice on how they can make the best use of the available time. The guide can include activities relating to the topic.

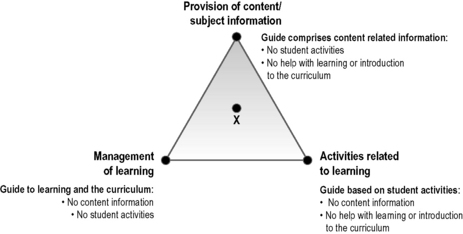

Guides can be provided in printed or electronic format. An extract from a study guide for junior doctors is shown in Appendix 4. Icons and the page layout are used to facilitate learning. The design of a study guide varies depending on how it is intended the student will make use of it. The position of a study guide on the study guide triangle (Fig. 23.1) indicates the extent to which the guide has been designed to:

A guide can be positioned anywhere on the study guide triangle, depending on its intended use.

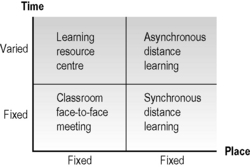

Distance learning

Students working independently have a choice of when and where they study (Fig. 23.2). This may be at a central learning resource centre on campus, in a peripheral training facility at a distance from the teacher and the main campus, or at home. In synchronous learning the time is fixed and students interact live with other students or with the teacher. A typical example of this is a telephone or web-conference or an online chat room. Working asynchronously, students may choose the time at which they wish to learn and communicate with other students and the teacher. This may be done using email or bulletin boards.

Reflect and react

1. Consider whether you have the right balance in your teaching programme between face-to-face contact with your students and opportunities for students to work on their own. Is time scheduled in the curriculum for independent learning?

2. Do you do enough to help the students maximise the benefits of learning on their own through the provision of advice and/or study guides to support the students’ learning?

3. Are the benefits to be gained from the use of the new technologies sufficiently exploited in your programme?

4. Consider the level of autonomy that you offer the student and the control that you exert over their learning. How does this change as the student progresses through the course?

5. Consider whether you might work on the creation of learning resource material and if so with whom you might collaborate.

Dron J. Control and Constraint in e-Learning: Choosing When to Choose. London: IDEA Group Publishing; 2007.

Laidlaw J.M., Hesketh E.A., Harden R.M. Study guides. In Dent J.A., Harden R.M., editors: A Practical Guide for Medical Teachers, third ed., London: Elsevier, 2009. (Chapter 27).

This chapter outlines important trends in independent learning.