CHAPTER 21 Imperforate Anus

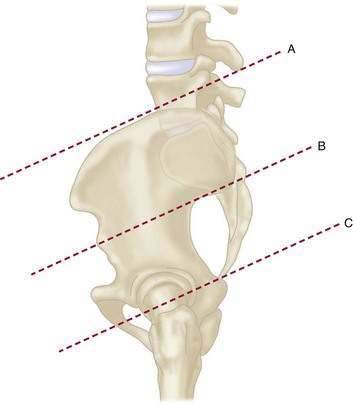

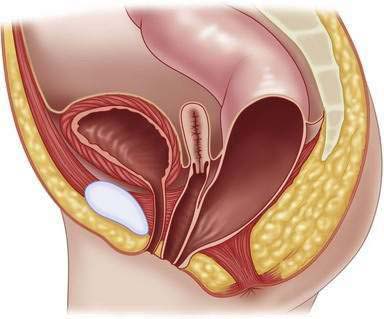

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

Step 2: Preoperative Considerations

Associated Defects

Sacrum and Spine

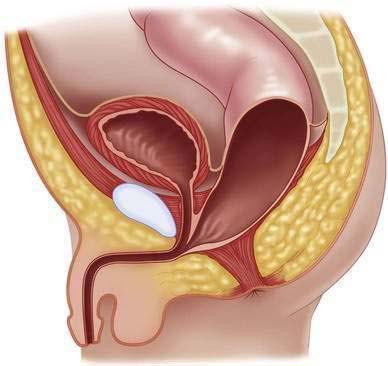

Urogenital Defects

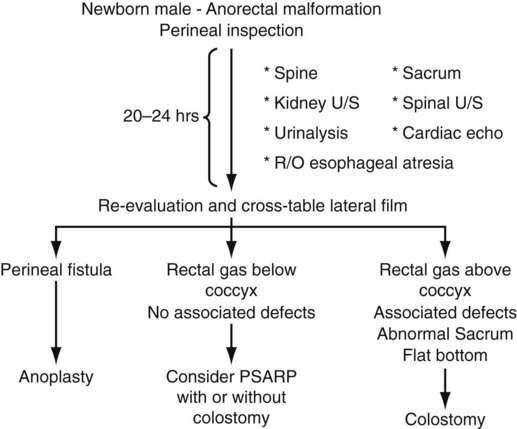

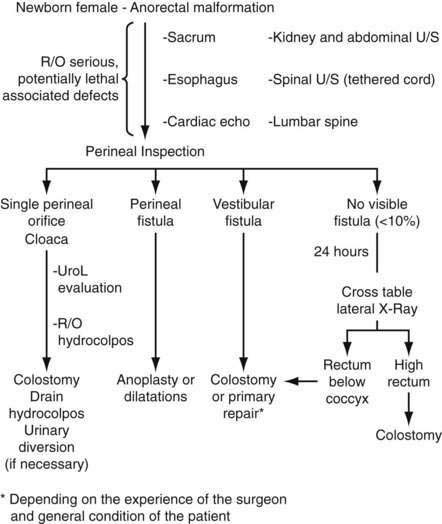

Management of Anorectal Malformations During the Neonatal Period

Males

Females

High-Pressure Distal Colostography

Step 3: Operative Steps

Males

Perineal (Cutaneous) Fistula

Rectourethral Fistula

Rectobladder Neck Fistula

Imperforate Anus Without Fistula

Rectal Atresia

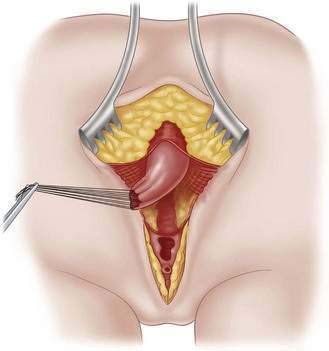

Females

Vestibular Fistula

Colostomy

Definitive Repair

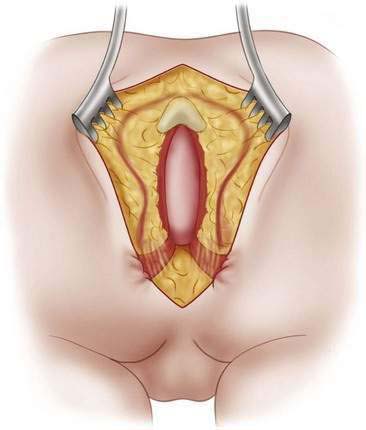

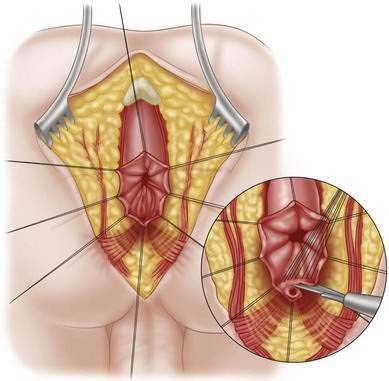

Incision

Perineal (Cutaneous) Fistulas

Rectourethral Fistula

Rectobladder Neck Fistula

Imperforate Anus Without Fistula

Rectal Atresia and Stenosis

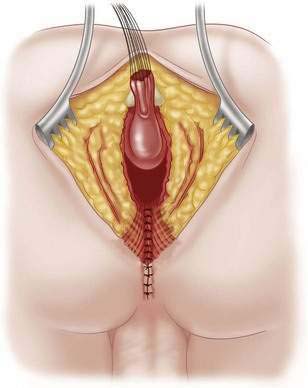

Repair in Girls

Vestibular Fistula

Rectovaginal Fistula

Step 4: Postoperative Care

Step 5: Pearls and Pitfalls

Belizon A, Levitt MA, Shoshany G, et al. Rectal prolapse following posterior sagittal anorectoplasty for anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:192-196.

Belman BA, King LR. Urinary tract abnormalities associated with imperforate anus. J Urol. 1972;108:823-824.

Bianchi DW, Crombleholme TM, D’Alton ME. Cloacal exstrophy. In Fetology: Diagnosis and management of the fetal patient, 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010; pp. 459-466

Boemers TM, de Jong TP, van Gool JD, Bax KM. Urologic problems in anorectal malformations. Part 2: Functional urologic sequelae. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(5):534-537.

deVries P, Peña A. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty. J Pediatr Surg. 1982;17:638-643.

Drake JM. Occult tethered cord syndrome: not an indication for surgery. J Neurosurg. 2006;104(5):305-308.

Falcone RA, Levitt MA, Peña A, Bates MD. Increased heritability of certain phenotypes. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:124-128.

Georgeson K. Laparoscopic-assisted anorectal pull-through. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16(4):266-269.

Georgeson KE, Inge TH, Albanese CT. Laparoscopically assisted anorectal pull-through for high imperforate anus: a new technique. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:927-931.

Goon HK. Repair of anorectal anomalies in the neonatal period. Pediatr Surg Int. 1990;5:246-249.

Gross GW, Wolfson PJ, Peña A. Augmented-pressure colostogram in imperforate anus with fistula. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21:560-563.

Hong AR, Rosen N, Acuña MF, et al. Urological injuries associated with the repair of anorectal malformations in male patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:339-344.

Levitt M, Falcone R, Peña A. Pediatric fecal incontinence. In: Fecal incontinence: Diagnosis and treatment. New York: Springer; 2007:341-350.

Levitt M, Peña A. Surgery and constipation: when, how, yes, no? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:S58-S60.

Levitt MA, Stein DM, Peña A. Gynecological concerns in the treatment of teenagers with cloaca. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(2):188-193.

Livingston J, Elicevik M, Crombleholme T, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of persistent cloaca: a 10 year review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(6):S63.

Peña A, deVries P. Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty: important technical considerations and new applications. J Pediatr Surg. 1982;17:796-881.

Pena A, Grasshoff S, Levitt A. Reoperations for anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:318-325.

Peña A, Guardino K, Tovilla JM, et al. Bowel management for fecal incontinence in patients with anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33(1):133-137.

Peña A, Levitt M. Colonic inertia disorders in pediatrics. Curr Prob Surg. 2002;39(7):661-730.

Peña A, Migotto-Krieger M, Levitt MA. Colostomy in anorectal malformations: a procedure with serious but preventable complications. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:748-756.

Seldon NR. Occult tethered cord syndrome: the case for surgery. J Neurosurg. 2006;104(5):302-304.

Shaul DB, Harrison EA. Classification of anorectal malformations—initial approach, diagnostic tests, and colostomy. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1997;6(4):187-195.

Stoll C, Alembik Y, Dott B. Associated malformations in patients with anorectal anomalies. Eur J Med Genet. 2007;50(4):281-290.

Vick LR, Gosche JR, Boulanger SC, Islam S. Primary laparoscopic repair of high imperforate anus in neonatal males. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1877-1881.