Chapter 6 Impairment Rating and Disability Determination

This chapter includes a brief introduction to the latest (sixth) edition to the American Medical Association (AMA) Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment,48 a reference text that can be likened to an updated tax code for impairment rating. The sixth edition chief editor is Robert D. Rondinelli, a physiatrist. In contrast to previous editions of the AMA Guides, it is fortunate that the sixth edition moves toward a more functional view of impairment rating.

This chapter is not intended to be used to determine impairment or disability for a specific patient. The reader is referred in this regard to the AMA Guides,48 which outlines a method for rating impairment for virtually every organ system. In practical terms, however, most impairment and disability evaluations focus on musculoskeletal disorders.

Disability Agencies

The VA has its own disability benefits program, described as follows:

Disability compensation is a monetary benefit paid to veterans who are disabled by an injury or disease that was incurred or aggravated during active military service. These disabilities are considered to be service-connected. Disability compensation varies with the degree of disability and the number of veteran’s dependents, and is paid monthly.60

Definitions: Disability and Impairment

Social Security Administration

Agencies have different definitions of disability. For example, the SSA defines disability as “the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity … by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment that can be expected to result in death or that has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months.”56 To determine work disability, the SSA uses a sequential evaluation process that focuses on applicants’ diagnoses, not their functional abilities. Although the SSA’s five-step process assesses earnings and impairment severity, it is not until late in the process that functional capacity is assessed. An applicant may appeal an unfavorable disability determination, which can markedly extend processing time. Unlike the VA, the SSA does not award benefits for “partial disability.”

AMA Guides, Sixth Edition

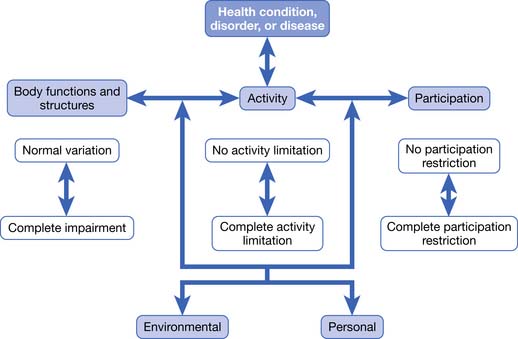

The latest edition of the AMA Guides48 uses as its foundation the World Health Organization model of disablement. This model is called the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) and is illustrated in Figure 6-1. There are three key inputs to the ICF model determining disability, paraphrased here from the AMA Guides48:

Note that body functions are physiologic—for example, the ability of the upper limb to generate accurate motion and strength. Body structures are anatomic—for example, the upper limb itself. Either or both can be compromised to produce impairment. The inability to carry out tasks, such as not being able to comb one’s hair, is an activity limitation. The inability to be involved in a typical life situation, such as being gainfully employed and interacting with one’s peers, is a participation restriction. Note that there is not a necessary correlation between activity limitation and participation restriction.

FIGURE 6-1 The World Health Organization ICF Model of Disablement.

(Redrawn from Rondinelli RD, editor: Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment, ed 6, Chicago, 2008, American Medical Association Press.)

In the ICF model, there is no linear progression from pathology to impairment to disability and to participation restriction. The AMA Guides justifies the use of the ICF model as follows48:

Impairment rating within the latest AMA Guides10 has more weight given to loss of function in the determination of impairment rating. This is defined as a “consensus-derived percentage estimate of loss of activity reflecting severity for a given health condition, and degree of associated limitations in terms of ADLs [italics added].”

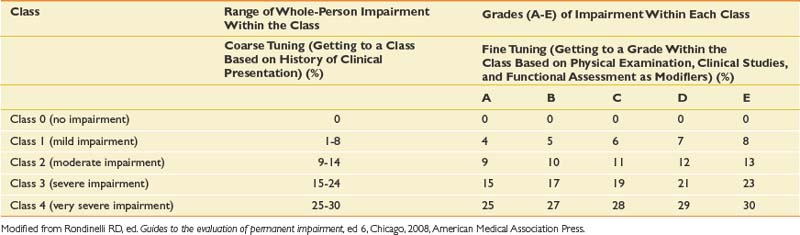

This chapter is not meant to provide the reader with the necessary skills to do actual impairment ratings, which can be fairly complex and detailed. However, a brief sketch of the approach to impairment rating based on the latest AMA Guides is given here48:

Note that there is a new emphasis on functional history with this edition of the AMA Guides. Loss of function is assessed in part by self-report measures that claimants may fill out at the time of their impairment evaluations. Different measures are used for different kinds of disorders; for example, the QuickDASH is used for disorders of the hand, while the Pain Disability Questionnaire is used for evaluating functional limitations involving the spine. The important general point is that impairment ratings in the AMA Guides sixth edition incorporate subjective information from claimants about their burden of illness. The significance of this change in the Guides is modest, however, because functional history plays a relatively minor role, modulating the grade within a given class. The primary emphasis in the Guides continues to be on objective findings rather than subjective history in the impairment rating process.

Further Thoughts on Impairment Versus Disability

Roles of Physicians in Disability Evaluation

Many physicians do not seek opportunities to perform disability evaluations because they are uncomfortable evaluating disability in patients whom they are treating. They correctly perceive that the process of disability evaluation places a physician between the interests of the patient and those of an insurance company or disability agency. In the best of circumstances, this can seem to the physician like trying to fit a round peg into a square hole, because the categories of disability established by such agencies often do not match the clinical realities of patients.

The concerns that treating physicians have about doing disability evaluations appear to fall into two categories: knowledge deficits and ethical concerns. Physicians who work primarily as clinicians are likely to be unfamiliar with the disability laws and regulations relevant to their patients, and the disability agencies that administer them. They are also likely to lack expertise in the mechanics of rating impairment, such as those detailed in the AMA Guides,48 and in the methods that can be used to assess work ability.20,21,31,33,49

Treating physicians can be concerned about conflicts between the clinical role they normally play when they treat patients and the adjudicative role that is required during a disability evaluation. Informal observation as well as examination of the limited literature on these roles26,42,58,65 suggests several differences between the two roles. For example, physicians performing disability evaluations are expected to focus on objective findings and legal responsibility, including causation, for an examinee’s disorder, but these are not the main concern of physicians when they provide clinical treatment.46 As Sullivan and Loeser58 have noted, significant ethical issues arise when physicians switch back and forth between these two roles.

Assessing Self-Reports of Patients Regarding Physical Capacity

A key challenge is to combine examinees’ self-reports regarding their incapacitation with objective medical information relevant to their injury.47 Note that the definition of “objective medical information” is not always clear. Unfortunately the existence of objective medical findings often depends on the degree to which technologies have advanced. For example, before myelography became available, radiographic studies (i.e., x-ray films) did not demonstrate objective findings for patients with radiculopathies.

A position somewhere between these two extremes is probably most appropriate. The perceptions that patients have about their abilities certainly should not be ignored or discounted. As a practical matter, research demonstrates that these self-appraisals are important predictors of whether patients with pain problems will perform well on physical tests or will succeed in terminating their disability, or both.14,15,23–25,30 Physicians who make disability decisions without considering patients’ appraisals are discarding valuable data. As a result, their decisions can go awry in two ways. First, they can pressure patients to return to work in jobs that the patients are realistically not capable of performing. Second, they can be ineffective in resolving disability issues. Consider patients who are released to work by their treating physician or by an independent medical examiner even though they are convinced that they are unable to work. Such patients are likely to retain an attorney and start a protracted legal battle regarding their work status.

But the fact that patients’ perceptions are important does not mean that they are valid or immutable. In fact, research on patients with disability related to chronic pain suggests the opposite: some often have distorted views of their capabilities, and these views are modifiable.1,12,28,35 Disability evaluators need to consider the validity of a patient’s stated activity limitations in light of the biomedical information available and their assessment of the patient’s credibility. Evaluators should reserve the right to challenge the patient’s self-assessments and to make decisions that are discordant with these assessments.

Blending Administrative Imperatives With Patient Realities

The assumption of transparency is problematic. This assumption is so pervasive that most physicians, and essentially all disability adjudicators, accept it without question. From a historical perspective, however, it is apparent that physicians have not always believed that incapacitation from trauma should be transparent. In fact, when the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program was being considered by Congress during the 1950s, physician groups almost uniformly protested that they would not be able to do the assessments that were envisaged in the SSDI legislation.41

For some impairments, objective criteria can be used in a transparent manner. For example, physicians have straightforward tools to quantify impairment stemming from amputations, complete spinal cord injuries, or clear cases of radiculopathy that are supported by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence of a focal disk herniation. However, in many medical conditions, including many musculoskeletal and neurologic disorders, physicians cannot easily identify injuries to organs or body parts that lead to the activity limitations that examinees report. Again the example of spinal facet joint injuries is given. Carefully controlled studies since the 1990s have documented that cervical facet joint injury is the probable primary pain generator for 50% of whiplash patients with nonradicular neck pain.2,3,37

More recently, animal and postmortem biomechanical studies of cervical facet joint injury have strengthened these clinical findings by documenting posttraumatic facet capsular laxity,27 as well as pain behavioral changes34 and histologic axonal changes29 in animals exposed to facet joint distensions simulating whiplash injury. Despite these advances, documenting facet joint injury for impairment rating remains problematic. Although cervical facet joints show up on MRI scanning, injury to them, or pain stemming from them, is generally not detected. Conversely, facet joint arthropathy, when detected with imaging studies, can be seen among asymptomatic patients and cannot be taken as a reliable physical sign of facet joint injury or impairment.52,54 There are guidelines for giving impairment for motion segment instability, which might be associated with increased facet capsular laxity, but the threshold for giving impairment for such instability is likely not sensitive.

In addition, there is increasing evidence that patients with chronic whiplash pain, chronic low back pain, or both, develop changes in central nervous system functioning that augment the severity of their chronic pain.11,18,32,57 These changes are also difficult to quantify but can become the basis for significant loss of function and vocational disability. Disability evaluators cannot easily rate impairment for this common clinical scenario. More importantly, they cannot offer a clear correlation between severity of impairment and severity of disability.

In the latest AMA Guides, facet injury after whiplash is formally acknowledged for the first time as a ratable impairment.48 However, it is grouped as “nonspecific chronic, or chronic recurrent neck pain (also known as chronic sprain/strain, symptomatic degenerative disk disease, facet joint pain, chronic whiplash, etc.).” This carries a maximum 8% whole-person impairment.

By contrast, a patient who has a documented severe facet joint injury resulting in facet joint neurotomy might become disabled from heavy physical work, require vocational retraining, and might become dependent upon repeated neurotomies indefinitely at approximate 8- to 12-month intervals for adequate pain relief.53 This can represent a huge burden of future medical and vocational costs projected over the person’s lifetime.

Even in the case of radiculopathy, a condition thought to be fairly well assessed within the AMA Guides, there are pitfalls for assessing spinal impairment. Research has shown that most lumbar MRI findings among patients with radiculopathy do not correlate well with their pain diagrams and physical examination findings, except in the rare case of a disk extrusion or severe spinal stenosis, or both.4 In practice, most MRI findings do not demonstrate such severe pathology. In addition, there is increasing understanding that radiculopathy is an inflammatory condition and might not depend on demonstrable nerve root compression by MRI scanning. There can be clear clinical evidence of radiculopathy causing significant functional impairment in the absence of MRI-detected nerve root compression.55,64

These examples highlight two problems. First, it is can be difficult to identify an anatomic or physiologic abnormality that rationalizes the claim of incapacity. This problem occurs frequently. For example, data from the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that more than 40% of work injuries requiring time off work are coded as sprains/strains.59 Although such injuries might be supported by objective findings, such as a complete tear of the anterior cruciate ligament documented by MRI scan, physicians often diagnose a sprain/strain when a patient complains of pain without well-defined objective findings. Second, a given structural abnormality might be associated with a wide range of functional loss among different patients. In this regard, it is worth noting that there is little empirical evidence to validate the quantitative impairment percentages given in the AMA Guides.

Topics Addressed in Disability Evaluations

Physicians are typically asked to address the following when they conduct disability evaluations:

A fundamental goal of the disability evaluation process is to determine whether a patient can work. From this perspective, the first five items can be viewed as preliminary items that set the stage for addressing the sixth and crucial question.

Practical Strategies for Disability Evaluation

The discussion below is largely based on our experiences treating patients in clinical settings, performing independent medical examinations, and consulting with the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. Scientific data on the reliability and validity of disability evaluations are limited.7–944 In the absence of scientific data, it is impossible to say what decision-making strategies are appropriate when performing disability evaluations. In this ambiguous situation, it is easy for practitioners to fall into the trap of believing they are making valid judgments, when in fact their judgments are based on a variety of biases.19,46

Addressing the Main Questions

Causation and Apportionment

First, patients might have cumulative trauma disorders, which would be the result of an “occupational exposure” rather than a specific injury. In this setting, especially if the injured worker has had multiple employers during the period when the exposure appears relevant, the issue of how to distribute liability becomes critical. In this case, there is a need for apportionment. Apportionment is an attempt to distribute causation among multiple possible sources. In the latest edition of the AMA Guides, apportionment is described as “an allocation of causation among multiple factors that caused or significantly contributed to the injury or disease and resulting impairment.”48

Disability agencies differ significantly in the standards they set for establishing causation and the need for apportionment. Some agencies follow the principle that for an index injury to be accepted as the cause of a patient’s impairment, the injury must be the major factor contributing to the impairment. Others adopt a lower standard of causation that has been described as “lighting up.” When this standard applies, an index injury can be viewed as the cause of increased impairment even when the injury is minor and when preexisting impairment is severe. For example, consider an individual with a multiply operated knee who falls at work, develops an effusion in the knee, and is told by an orthopedist that he needs a total knee replacement. If the individual’s workers’ compensation carrier operated under the “lighting up” standard of causation, this person’s knee symptoms and need for a total knee replacement would be viewed as caused by the fall at work.

Apportionment analysis is most commonly described for impairment only48 and is determined by subtracting preexisting impairment, with respect to an index injury, from the current impairment. It is clear, however, that apportionment analyses for the cost of care and for disability are critical to the successful adjudication of compensable claims.

Some of the factors that help with a credible apportionment analysis include:

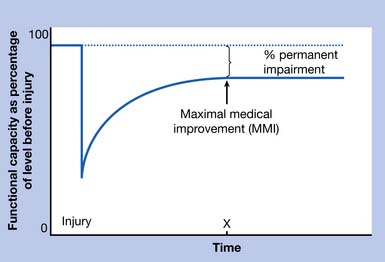

Need for Further Treatment

Disability agencies generally adopt an idealized model of the course of recovery after an injury. This model is shown in Figure 6-2. It embodies the assumption that people show rapid improvement after injury but then reach a plateau. Before patients reach this hypothetical plateau, they presumably can benefit from further treatment. When they reach the plateau, they are considered to have achieved maximal medical improvement (MMI). When a patient has reached MMI, insurance companies and disability agencies typically refuse to pay for additional medical care and attempt to make a final determination regarding a patient’s impairment and work capacity. From an administrative perspective, the model is convenient because it provides guidelines for intervention and decision making. For example, when a patient has reached point X on the graph, curative treatment should be abandoned, and a permanent partial impairment rating should be made.

The problem with this approach is that patients frequently have clinical problems that are hard to conceptualize in terms of the idealized recovery shown in Figure 6-2. First, it is not clear that patients with repetitive strain injuries or chronic spinal pain39,61 follow the trajectory shown in Figure 6-2. Second, patients can have comorbidities that complicate recovery and make it difficult to determine when they have reached MMI. An example is a patient with diabetes who has a work-related carpal tunnel syndrome in addition to a peripheral polyneuropathy. Third, many who use the MMI concept fail to remember that a patient who has reached maximal benefit from a particular kind of treatment might not have reached maximal benefit from treatment in general. For example, consider a patient who is examined 6 months after a low back injury. Assume that treatment has consisted entirely of chiropractic care during the 6-month interval, and that the patient has not shown any measurable improvement during the past 2 months. This patient might be judged to have reached maximal medical benefit from chiropractic care, but an examining physician would understandably be uncertain about whether the patient could benefit from physical therapy, epidural corticosteroids, lumbar surgery, aggressive use of various medications, or other therapies that might not be offered by the chiropractor. This problem is not just a hypothetical one, because examiners routinely find that some patients with chronic conditions have not had exposure to all reasonable treatments for their condition.

Impairment

Once a physician decides that an impairment rating is appropriate for a patient, the rating itself is a fairly mechanical task that is based on formulas and procedures described in various texts, or in manuals published by disability agencies. The agency that requests an impairment rating typically specifies the system that physicians are required to use. For example, the AMA Guides48 describes an impairment rating system that is used by multiple jurisdictions. Some states have their own impairment rating systems. To perform an impairment evaluation according to the rules of a jurisdiction, the physician needs to be familiar with the system used by that jurisdiction.

Physical Capacities Assessment

Another way to obtain physical capacities data is to refer a patient for a functional capacities evaluation (FCE), also called a performance-based physical capacities evaluation.31,33,49 FCEs are formal, standardized assessments typically performed by physical therapists. They usually last from 2 to 5 hours. The therapist gathers information about a patient’s strength, range of motion, and endurance in various tasks, preferably ones that simulate the type of work that the patient is expected to do. As noted by King et al.,31 FCEs are popular with insurance carriers and attorneys because they provide objective performance data. In their comprehensive review, however, King et al. also noted that there is a paucity of data that validate FCEs against actual job performance.

Pransky and Dempsey43 noted that a generalized FCE has less utility than one simulating a specific job requirement, in terms of predicting actual job performance. However, tailoring the FCE process to a specific job requires more resources and is likely not practical in most scenarios. Gross and Battie20–22 noted that for both patients with low back pain and those with upper limb disorders, FCE results are poor predictors of termination of time loss benefits and return to work. Clearly, psychological factors and coping skills play an important role in predicting return to work, and these variables are not well captured within a standardized FCE.

The FCE can also gauge the level of the patient’s effort, to help address the possibility of malingering, secondary gain, or excessive fear of exertion after injury. As an example, full effort is assumed if the coefficients of variation—the standard deviation divided by the mean as a percentage—are less than 10% to 15% for repeated hand grip measurements blinded from the patient. As discussed in a recent review,43 however, the ability to detect submaximal effort is imperfect at best.

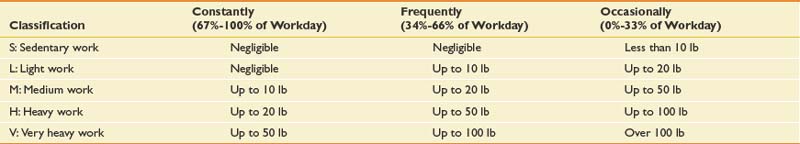

In practice, a category between none and occasional is useful, described as “Seldom” or “Rare,” which is defined as 1% to 10% of the time. Also available from the Dictionary of Occupational Titles is a broad definition of job categories by physical lifting requirements (Table 6-2).

Ability to Work

The ability of a patient to work is the key issue in most disability evaluations. Assessing employability is difficult, and there is no simple set of techniques to apply when a decision about employability is requested. Box 6-1 outlines issues that should be considered when judging a patient’s employability.

Box 6-1 Issues to Consider in Determining Employability

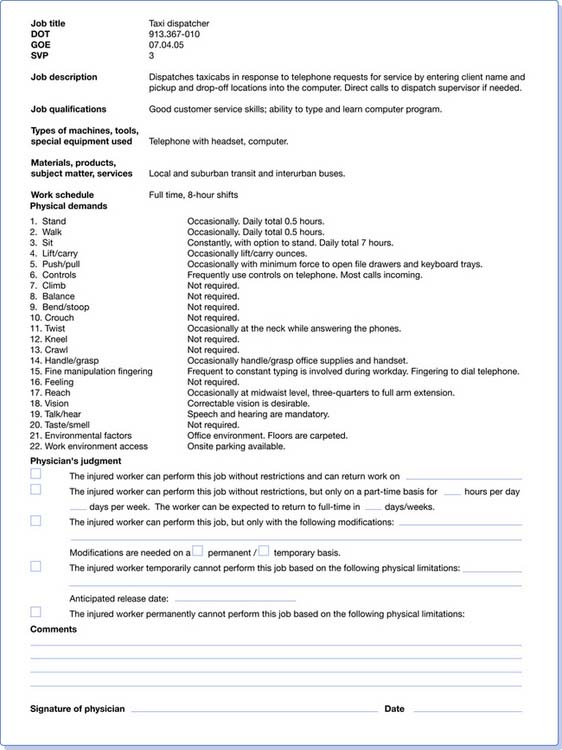

A physician makes a judgment about a patient’s employability by balancing the patient’s functional capacities (or limitations) against the functional demands of jobs for which the patient is being considered. Concerning job demands, the physician usually has to rely upon information provided by vocational rehabilitation counselors or employers. In workers’ compensation claims, vocational rehabilitation counselors often prepare formal job analyses. Figure 6-3 gives a sample job analysis. Note that the job analysis form includes a section in which the evaluating physician is asked to give an opinion about whether the worker can perform the job.

Sometimes physicians are presented with “trick” questions dealing with employability. As an example, a physician is treating a patient with chronic low back pain who has failed multiple spine surgeries and continues to complain of relentless pain despite the implantation of an intrathecal opiate delivery system. The physician believes it is unrealistic for this patient to return to competitive employment. A disability agency asks the physician whether the patient can work as a telephone solicitor. This question poses a dilemma. If the physician says “Yes,” the patient’s disability benefits will probably be terminated. If the answer is “No,” the physician is implicitly saying that the low back pain prevents the patient from doing a job that has few physical demands. This can represent an ethical dilemma, and the physician ultimately must use clinical judgment, at the same time addressing guidelines within the disability system.

Further Special Issues in Disability Evaluations

Possibility of Deception

Physicians need to be aware of the possibility that any of the participants in a disability claim can have a hidden agenda. Opportunities for deception are particularly notable in workers’ compensation claims. An extensive medical literature on secondary gain, compensation neurosis, and malingering has dealt with hidden agendas of patients.5,17,36,40,62

Behavioral signs suggesting psychological distress that can be observed in patients with chronic pain have been inappropriately used within a medicolegal setting as evidence for malingering. The most famous example is the Waddell signs, developed by the well-known spinal surgeon, Dr. Gordon Waddell, who urged his fellow surgeons “to operate on a patient, not a spine,” as this “may save years of coping with the human wreckage caused by ill-considered surgery on the lumbar discs.”63 There have been numerous articles reappraising the Waddell signs, one of which has been coauthored by Dr. Waddell himself,38 making clear that these behavioral signs do not have a role in the detection of malingering.13,16

Other parties to a workers’ compensation claim, including employers and adjudicators for disability agencies, can also have hidden agendas. Their agendas have been ignored almost completely in research on disability, so the physician needs to use clinical judgment in deciding whether participants in a disability claim are behaving in a deceptive manner. The physician should consider the following:

Objective Findings

As noted earlier, the term “objective findings” is not precisely defined.47 Some examiners believe that objective data refer to laboratory or physical findings that are measurable, valid, and reliable and are not subject to voluntary control or manipulation by a patient. Objective findings can be contrasted with “subjective findings” such as patients’ reports of activity restrictions caused by pain. A lot of clinically important examination findings, however, including range of motion (ROM), tested strength, and some muscle stretch reflex findings might be described as “semiobjective.” They are objective in the sense that they can be observed and measured, but they might not be completely reliable because patients can voluntarily modify them. Most adjudicators who request objective findings are not aware of these subtleties. The AMA Guides generally accepts physical examination findings as objective data, even if they are able to be voluntarily manipulated by the patient.

The latest edition of the AMA Guides48 has less emphasis on ROM measurements for determining spinal impairments as compared with prior editions. This has not been done because ROM is subject to voluntary control, but because ROM has not correlated well with loss of function and probable impairment in the spinal region.66

Upper limb ROM determination remains important in the AMA Guides.48 Active ROM is considered to reflect true function better than passive ROM. The AMA Guides also warns that if there is a significant discrepancy between active and passive ROM, however, there should be a clear physiologic basis (e.g., full rotator cuff tear) for the discrepancy. The possibility of symptom magnification and self-inhibition by the patient should be specifically addressed.

Conclusion

Note that there is strikingly little published information on the subject of disability evaluation, despite the fact that millions of evaluations are done each year in the United States. At a very basic level, there is very little evidence about whether the decisions made by large agencies such as the SSA are overall good or bad—that is, whether the SSA is awarding benefits to individuals who are truly disabled, or is withholding them from individuals who are truly unable to work.45,50,51

1. Alaranta H., Rytokoski U., Rissanen A., et al. Intensive physical and psychosocial training program for patients with chronic low back pain: a controlled clinical trial. Spine. 1994;19:1339-1349.

2. Barnsley L., Lord S., Wallis B., et al. False-positive rates of cervical zygapophysial joint blocks. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:124-130.

3. Barnsley L., Lord S.M., Wallis B.J., et al. The prevalence of chronic cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash. Spine. 1995;20:20-25. discussion 26

4. Beattie P.F., Meyers S.P., Stratford P., et al. Associations between patient report of symptoms and anatomic impairment visible on lumbar magnetic resonance imaging. Spine. 2000;25:819-828.

5. Bellamy R. Compensation neurosis: financial reward for illness as nocebo. Clin Orthop. 1997;336:94-106.

6. Carragee E.J. Validity of self-reported history in patients with acute back or neck pain after motor vehicle accidents. Spine J. 2008;8:311-319.

7. Chibnall J.T., Tait R.C., Andresen E.M., et al. Race and socioeconomic differences in post-settlement outcomes for African American and Caucasian Workers’ Compensation claimants with low back injuries. Pain. 2005;114:462-472.

8. Clark W., Haldeman S. The development of guideline factors for the evaluation of disability in neck and back injuries: Division of Industrial Accidents, State of California. Spine. 1993;18:1736-1745.

9. Clark W.L., Haldeman S., Johnson P., et al. Back impairment and disability determination: another attempt at objective, reliable rating. Spine. 1988;13:332-341.

10. Cocchiarella L., Andersson G.B.J., editors. Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment, ed 5, Chicago: American Medical Association Press, 2001.

11. Curatolo M., Petersen-Felix S., Arendt-Nielsen L., et al. Central hypersensitivity in chronic pain after whiplash injury. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:306-315.

12. Estlander A.M., Mellin G., Vanharanta H., et al. Effects and follow-up of a multimodal treatment program including intensive physical training for low back pain patients. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1991;23:97-102.

13. Fishbain D.A., Cole B., Cutler R.B., et al. A structured evidence-based review on the meaning of nonorganic physical signs: Waddell signs. Pain Med. 2003;4:141-181.

14. Fishbain D.A., Cutler R.B., Rosomoff H.L., et al. Impact of chronic pain patients’ job perception variables on actual return to work. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:197-206.

15. Fishbain D.A., Cutler R.B., Rosomoff H.L., et al. Prediction of “intent,” “discrepancy with intent,” and “discrepancy with nonintent” for the patient with chronic pain to return to work after treatment at a pain facility. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:141-150.

16. Fishbain D.A., Cutler R.B., Rosomoff H.L., et al. Is there a relationship between nonorganic physical findings (Waddell signs) and secondary gain/malingering? Clin J Pain. 2004;20:399-408.

17. Fishbain D.A., Rosomoff H.L., Cutler R.B., et al. Secondary gain concept: a review of the scientific evidence. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:6-21.

18. Giesecke T., Gracely R.H., Grant M.A., et al. Evidence of augmented central pain processing in idiopathic chronic low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:613-623.

19. Gilovich T. How we know what isn’t so: the fallibility of human reason in everyday life. New York: Free Press; 1991.

20. Gross D.P., Battie M.C. The prognostic value of functional capacity evaluation in patients with chronic low back pain. 2. Sustained recovery. Spine. 2004;29:920-924.

21. Gross D.P., Battie M.C. Does functional capacity evaluation predict recovery in workers’ compensation claimants with upper extremity disorders? Occup Environ Med. 2006;63:404-410.

22. Gross D.P., Battie M.C., Cassidy J.D. The prognostic value of functional capacity evaluation in patients with chronic low back pain. 1. Timely return to work. Spine. 2004;29:914-919.

23. Hazard R.G., Bendix A., Fenwick J.W. Disability exaggeration as a predictor of functional restoration outcomes for patients with chronic low-back pain. Spine. 1991;16:1062-1067.

24. Hidding A., van Santen M., De Klerk E., et al. Comparison between self-report measures and clinical observations of functional disability in ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:818-823.

25. Hildebrandt J., Pfingsten M., Saur P., et al. Prediction of success from a multidisciplinary treatment program for chronic low back pain. Spine. 1997;22:990-1001.

26. Holleman W.L., Holleman M.C. School and work release evaluations. JAMA. 1988;260:3629-3634.

27. Ivancic P.C., Ito S., Tominaga Y., et al. Whiplash causes increased laxity of cervical capsular ligament. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2008;23:159-165.

28. Jensen M.P., Turner J.A., Romano J.M. Correlates of improvement in multidisciplinary treatment of chronic pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:172-179.

29. Kallakuri S., Singh A., Lu Y., et al. Tensile stretching of cervical facet joint capsule and related axonal changes. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:556-563.

30. Kaplan G.M., Wurtele S.K., Gillis D. Maximal effort during functional capacity evaluations: an examination of psychological factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:161-164.

31. King P.M., Tuckwell N., Barrett T.E. A critical review of functional capacity evaluations. Phys Ther. 1998;78:852-866.

32. Koelbaek Johansen M., Graven-Nielsen T., Schou Olesen A., et al. Generalised muscular hyperalgesia in chronic whiplash syndrome. Pain. 1999;83:229-234.

33. Lechner D.E. Functional capacity evaluation. In: King P.M., editor. Sourcebook of occupational rehabilitation. New York: Plenum Press, 1998.

34. Lee K.E., Thinnes J.H., Gokhin D.S., et al. A novel rodent neck pain model of facet-mediated behavioral hypersensitivity: implications for persistent pain and whiplash injury. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;137:151-159.

35. Lipchik G.L., Milles K., Covington E.C. The effects of multidisciplinary pain management treatment on locus of control and pain beliefs in chronic non-terminal pain. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:49-57.

36. Loeser J.D., Henderlite S.E., Conrad D.A. Incentive effects of workers’ compensation benefits: a literature synthesis. Med Care Res Rev. 1995;52:34-59.

37. Lord S.M., Barnsley L., Wallis B.J., et al. Chronic cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash: a placebo-controlled prevalence study [see comments]. Spine. 1996;21:1737-1744. discussion 1744–1745

38. Main C.J., Waddell G. Behavioral responses to examination: a reappraisal of the interpretation of “nonorganic signs.”. Spine. 1998;23:2367-2371.

39. McGorry R.W., Webster B.S., Snook S.H., et al. The relation between pain intensity, disability, and the episodic nature of chronic and recurrent low back pain. Spine. 2000;25:834-841.

40. Mendelson G. Psychiatric aspects of personal injury claims. Springfield: Charles C Thomas; 1988.

41. Osterweis M., Kleinman A., Mechanic D. Pain and disability: clinical, behavioral, and public policy perspectives. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1987.

42. Peterson K.W., Babitsky S., Beller T.A., et al. The American Board of Independent Medical Examiners. J Occup Environ Med. 1997;39:509-514.

43. Pransky G.S., Dempsey P.G. Practical aspects of functional capacity evaluations. J Occup Rehabil. 2004;14:217-229.

44. Reville R.T. Institute for Civil Justice (US), California. Commission on Health and Safety and Workers’ Compensation. An evaluation of California’s permanent disability rating system. Santa Monica: RAND Institute for Civil Justice; 2005.

45. Robinson J.P. Evaluation of function and disability. In Loeser J.D., editor: Bonica’s management of pain, ed 3, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

46. Robinson J.P. Pain and disability. In: Jensen T.S., Wilson P., Rice A., editors. Chronic pain. London: Edward Arnold, 2002.

47. Robinson J.P., Turk D.C., Loeser J.D. Pain, impairment, and disability in the AMA guides. J Law Med Ethics. 2004;32(191):315-326.

48. Rondinelli R.D., editor. Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairment, 6th edn, Chicago: American Medical Association Press, 2008.

49. Rondinelli R.D., Katz R.T. Impairment rating and disability evaluation. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000.

50. Rucker K.S., Metzler H.M. Predicting subsequent employment status of SSA disability applicants with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:22-35.

51. Rucker K.S., Metzler H.M., Kregel J. Standardization of chronic pain assessment: a multiperspective approach. Clin J Pain. 1996;12:94-110.

52. Saal J.S. General principles of diagnostic testing as related to painful lumbar spine disorders: a critical appraisal of current diagnostic techniques. Spine. 2002;27:2538-2545. discussion 2546

53. Schofferman J., Bogduk N., Slosar P. Chronic whiplash and whiplash-associated disorders: an evidence-based approach. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:596-606.

54. Schwarzer A.C., Wang S.C., O’Driscoll D., et al. The ability of computed tomography to identify a painful zygapophysial joint in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:907-912.

55. Shamji M.F., Allen K.D., So S., et al. Gait abnormalities and inflammatory cytokines in an autologous nucleus pulposus model of radiculopathy. Spine. 2009;34:648-654.

56. SSA. Disability evaluation under social security. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1994.

57. Sterling M., Jull G., Vicenzino B., et al. Sensory hypersensitivity occurs soon after whiplash injury and is associated with poor recovery. Pain. 2003;104:509-517.

58. Sullivan M.D., Loeser J.D. The diagnosis of disability. Treating and rating disability in a pain clinic. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:1829-1835.

59. U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work for State government and local government workers, 2008. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/iif/oshcdnew.htm. Accessed January 21, 2008.

60. VA. Federal benefits for veterans and dependents. Washington, DC: Superintendent of Documents; 2007. US Government Printing Office

61. van Tulder M., Koes B., Bombardier C. Low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2002;16:761-775.

62. Voiss D.V. Occupational injury. Fact, fantasy, or fraud? Neurol Clin. 1995;13:431-446.

63. Waddell G., McCulloch J.A., Kummel E., et al. Nonorganic physical signs in low-back pain. Spine. 1980;5:117-125.

64. Yamashita M., Ohtori S., Koshi T., et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the nucleus pulposus mediates radicular pain, but not increase of inflammatory peptide, associated with nerve damage in mice. Spine. 2008;33:1836-1842.

65. Ziporyn T. Disability evaluation: a fledgling science? JAMA. 1983;250:873-874. 879-880

66. Zuberbier O.A., Kozlowski A.J., Hunt D.G., et al. Analysis of the convergent and discriminant validity of published lumbar flexion, extension, and lateral flexion scores. Spine. 2001;26:E472-478.