Immunologic, Reactive, and Purpuric Disorders

Eulalia Baselga, Angela Hernández-Martín, Antonio Torrelo

Introduction

In this chapter, a number of non-related entities will be discussed. They appear grouped by convenience, and represent a heterogeneous group of genetic and acquired diseases with a common ground of an immunologic pathophysiology. Several disorders appear to represent hypersensitivity reactions. Purpuric eruptions will also be covered in this chapter. The differential diagnosis of purpura is extensive in neonates and young infants, and includes hematological disorders, infections, trauma, metabolic diseases, and iatrogenic disorders.

Annular erythemas

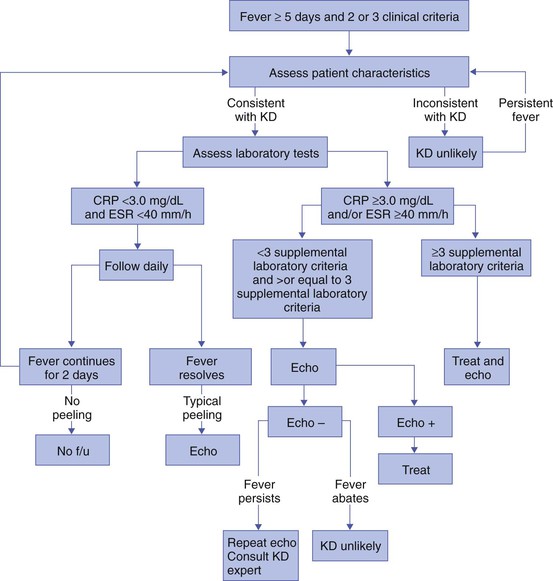

Annular erythema is a descriptive term that encompasses several entities of unknown etiology characterized by circinate polycyclic lesions that extend peripherally from a central focus.1–3 Because of subtle differences in clinical features, age of onset, duration of individual lesions, and total duration of the eruptions, a variety of descriptive terms have been coined for these disorders (Table 20.1). For prognostic reasons, it is useful to subdivide annular erythemas into transient and persistent forms.7 Transient forms include annular erythema of infancy and the less well-established entities erythema gyratum atrophicans transiens neonatale, neutrophilic figurate erythema of infancy and eosinophilic annular erythema. Persistent annular erythemas include erythema annulare centrifugum and familial annular erythema. The most important issue, however, is to exclude entities which require specific evaluation and treatment, such as neonatal lupus, tinea corporis, erythema chronicum migrans, erythema marginatum rheumaticum, erythema gyratum repens, and erythema multiforme. These ‘annular’ erythemas have distinctive clinical or histologic features and are considered below and elsewhere in this book.

TABLE 20.1

Annular erythemas

| Age of onset | Clinical features | Duration of individual lesions | Duration of eruption | Healing | Histopathology | |

| Transient forms | ||||||

| Annular erythema of infancy4 | Early infancy | Annular plaques No scaling or vesiculation Raised borders |

Days | Transient (5–6 weeks; cyclic course) | No residual lesions | Perivascular infiltrate of eosinophils |

| Erythema gyratum atrophicans transiens neonatale | Early infancy | Annular plaques No scaling or vesiculation Raised borders Atrophic center |

Days to months | Resolves before first year | No residual lesions | Perivascular monocytic infiltrate Epidermal atrophy DIF granular IgG; C3 and C4 at the BMZ |

| Eosinophilic annular erythema | Infants and adults | Annular plaques No scaling or vesiculation Raised borders |

Weeks to months | New lesions develop for months or years | No residual lesions | Perivascular infiltrate, very prominent eosinophils, no flame figures |

| Neutrophilic figurate erythema of infancy | Infants | Annular plaques No scaling or vesiculation Raised borders |

Weeks | Cyclic for a few years | No residual lesions | Neutrophils and leukocytoclasia without vasculitis |

| Persistent forms | ||||||

| Erythema annulare centrifugum5 | Adulthood, newborn period possible | Mild scaling may be seen at borders | Weeks | Persistent (months or years, with new lesions developing continuously) | Residual hyper-pigmentation | Superficial and deep perivascular cuff of lymphocytes |

| Familial annular erythema6 | Early infancy to puberty Autosomal dominant |

Possible vesiculation or scaling Geographic tongue may be associated Pruritus |

Days | Persistent (lifelong, short remissions) | Transient hyper-pigmentation | Superficial perivascular cuff of lymphocytes Spongiosis and parakeratosis |

Annular erythema of infancy

Annular erythema of infancy is a benign disease of early infancy characterized by the cyclic appearance of urticarial papules that enlarge peripherally, forming 2–3 cm rings or arcs with firm, raised, cord-like or urticarial borders.4,8 Adjacent lesions become confluent, forming arcuate and polycyclic lesions (Fig. 20.1). Neither vesiculation nor scaling is present at the border. The eruption is asymptomatic. Individual lesions resolve spontaneously without a trace within several days, but new lesions continue to appear in a cyclical fashion until complete resolution within the first year of life. Resolution of the lesions only during febrile episodes has been reported.9 A few cases lasting for years have been described.10,11

The cause of annular erythema is unknown, and there are no associated systemic findings. Histologic studies reveal a superficial and deep, dense, perivascular infiltrate of mononuclear cells and eosinophils. No flame figures are observed. The epidermis is normal or mildly spongiotic. Two variants with a predominantly eosinophilic and neutrophilic infiltrate have been described and renamed as eosinophilic annular erythema and neutrophilic figurate erythema of infancy, respectively.9,12

Laboratory studies are normal. Peripheral eosinophilia does not accompany tissue eosinophilia. Immunoglobulin levels, including IgE levels, are normal. The differential diagnosis should include other annular lesions of infancy (see below). No treatment is warranted because of the self-limited nature of the eruption.

Erythema gyratum atrophicans transiens neonatale is a less well-defined entity,13 characterized clinically by annular plaques with an erythematous border and an atrophic center. The lesions appear in the newborn period and resolve within the first year of life. Histologic findings include epidermal atrophy and a mild perivascular mononuclear infiltrate. Immunofluorescence studies reveal granular deposits of IgG, C3, and C4 at the dermoepidermal junction and around capillaries. Erythema gyratum atrophicans transiens neonatale possibly represents a variant of neonatal lupus erythematosus.5

Erythema annulare centrifugum

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a more persistent type of annular erythema that usually affects adults,14 but may also occur in children and rarely in newborns.7,11,15,16 Two clinicopathologic variants have been identified: a superficial and a deep variety. The lesions consist of annular and polycyclic plaques with an indurated border in the deep variety and a scaly border in the superficial variety. The scales characteristically lag behind the advancing border. Individual lesions resolve spontaneously after a few weeks, but new plaques continue to develop for years, or may be a lifelong condition. There is no associated pruritus. Erythema annulare centrifugum is thought to represent a hypersensitivity reaction to several trigger factors, including infectious agents (Candida,17 Epstein–Barr virus,16 Ascaris,18 Pseudomonas), drugs or foods,6,19 and neoplasia, especially in adults. Intradermal injection of candidin or trichophytin may reproduce the clinical lesions.15

Histologic features for superficial EAC consist of a dense, superficial, perivascular mononuclear infiltrate. There is also parakeratosis or epidermal spongiosis. The deep variant shows a sleeve-like arrangement of the superficial and deep lymphocytic infiltrate, and in some cases of melanophages, subtle vacuolar changes at the dermal–epidermal junction, and individual necrotic keratinocytes, which makes differential diagnosis from tumid lupus erythematosus very difficult.20,21

No therapy has been successful in all cases. Depending on the trigger factor, treatment agents that have been used include oral nystatin, oral amphotericin B, topical antifungals, antihistamines, disodium cromoglycate, and interferon-α.15,17

Familial annular erythema

Familial cases of annular erythema with autosomal dominant inheritance have rarely been described.22–24 The onset is in early infancy. Dermographism and pruritus was marked in the original cases. Lesions resolve with residual hyperpigmentation. Chronicity is the rule and geographic tongue may be associated.23

Differential diagnosis of annular erythemas

Differential diagnosis includes other eruptions with ring-like lesions, such as neonatal lupus, erythema multiforme, urticaria, urticarial lesions of pemphigoid, fungal infections, erythema chronicum migrans, and congenital Lyme disease.3,10,25,26

Serum antibody determinations (antinuclear, SS-A, and SS-B) are recommended to exclude neonatal lupus. Scraping any scaly lesion for KOH preparation is also advisable.

Neonatal lupus erythematosus

Neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE)27–34 is a disease of newborns caused by maternally transmitted autoantibodies. The major manifestations are dermatologic and cardiac. Skin findings are transient. Cardiac disease, which is responsible for the morbidity and mortality of NLE, begins in utero and affects the cardiac conduction system permanently. Other findings include hepatic and hematologic abnormalities. Mothers of infants with neonatal lupus have anti-Ro/SS-A autoantibodies in 95% of cases. Anti-La/SS-B and anti-U1RNP autoantibodies have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of NLE in a minority of patients.35,36

Cutaneous findings

Of infants with NLE, 50% have skin lesions, and congenital heart block is present in about 10%.27,34 Lesions commonly develop at a few weeks of age but may be apparent at birth, which suggests that ultraviolet (UV) radiation is not essential for the development of skin lesions.37 Ulcerations, bullae, and extensive atrophy may be present, particularly in cases that are present at birth38 and transient bullous lesions from severe vacuolar damage of the basal cell layer39 have been reported as unusual manifestations of NLE. These cases might more accurately be called ‘congenital LE’ rather than NLE (Fig. 20.2).

The more common skin manifestations of NLE fall into two main morphologies, papulosquamous and annular. Papulosquamous lesions are more common and are characterized by erythematous, nonindurated scaly plaques (Fig. 20.3), sometimes with an atrophic appearance (Fig. 20.4). In contrast to discoid lupus, scarring and follicular plugging are usually absent. The annular variant consists of well-circumscribed round plaques.40 Lupus profundus and generalized poikiloderma with erosions and patchy alopecia are rare manifestations.41,42

NLE lesions are most common on the face and scalp, predominantly affecting the periorbital and malar areas, often causing the ‘raccoon eyes’ appearance (Figs 20.4, 20.5), but can occur on virtually any body site. The eruption is frequently precipitated or aggravated by sun exposure, but lesions can develop in sun-protected areas (e.g., the diaper region, palms, and soles).37,43,44 Skin lesions are transient and cease to appear around the age of 6 months, after the disappearance of maternal antibodies. Transient or persistent hypopigmentation and epidermal atrophy may result (Fig. 20.6).34 Telangiectases, vascular ectasias resembling petechiae, persistent livedo or cutis marmorata, features of cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita, and widespread erythema mimicking an extensive capillary malformation have been observed but are much less common manifestations. In some cases, these findings can be an initial sign of NLE, occurring without preceding identifiable inflammatory lesions.33,45–47 A rare report of a case of NLE with a serological profile consistent with drug-induced lupus has been described in a newborn whose mother was treated with α-interferon during pregnancy.48

Extracutaneous findings

The most significant manifestation is isolated complete congenital heart block. More than 90% of such cases are due to NLE. Most patients have third-degree block, but progression from a second-degree block has been reported.49 Heart block can often be detected as early as 20 weeks’ gestation. Cardiomyopathy and other types of arrhythmias are associated with NLE.50

Transient liver disease, manifesting as hepatomegaly (with a picture of cholestasis) or elevation of liver enzymes,33,51–53 and thrombocytopenia or other isolated cytopenias, may occur.54 Petechiae and purpura have been described as presenting signs of NLE.55 Less common findings include thrombosis associated with anticardiolipin antibodies, hypocalcemia, spastic paraparesis, pneumonitis, and transient myasthenia gravis.56–58 Central nervous system (CNS) involvement has been emphasized in some reports, and can be asymptomatic, with only ultrasound and CT scan abnormalities, suggesting a transient phenomenon.59 However, hydrocephalus has been reported in 8% of children with NLE.60 NLE is a cause of chondrodysplasia punctata, seen in X-rays as stippling of the epiphyses and the spine.60 Between 30% and 50% of mothers of infants with NLE have a connective tissue disease, most commonly SLE or Sjögren syndrome. Most, however, are asymptomatic. The risk for developing overt connective tissue disease in these mothers is highly debated, with estimates ranging from 2% to more than 70%.34,61–66

Etiology and pathogenesis

Placentally transmitted maternal IgG autoantibodies are associated with the pathogenesis of NLE.67 The most commonly implicated autoantibodies have been anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B, present in 95% and 60–80%, respectively. A small subset of affected infants have neither Ro or La antibodies, but instead have anti-U1RNP.35,36 Antibodies against the 52/60-kD Ro and 48-kD La ribonucleoproteins are associated with heart block, whereas antibodies against the 50-kD La ribonucleoprotein are associated with cutaneous disease.68 Significantly more symptomatic mothers of children with congenital heart block have anti-La antibodies than do disease-matched mothers with unaffected children.69 Moreover, the mean level of anti-La seems to be higher in mothers of infants with congenital heart block than in mothers of children with cutaneous NLE.70 It is likely that the amount of maternal antibodies, rather than their presence, is associated with fetal injury.68

Why less than 5% of mothers with anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies give birth to affected children is not understood, nor is the fact that mothers of affected infants are often asymptomatic despite having these antibodies. Fraternal twins are often discordant for NLE, and NLE does not occur in every subsequent pregnancy. Genetic factors may be important for the development of NLE in children with maternal lupus antibodies. A link has been suggested between NLE rash and the allele HLA-DRB1*03, as well as a -308A polymorphism in the TNF-α gene.32 Alternatively, maternal and/or sibling microchimerism may play an additional role, as levels of microchimerism have been reported to correlate with NLE disease activity.71

Laboratory tests and histopathology

Serologic studies for autoantibodies in the mother and infant demonstrate anti-Ro, anti-La, and/or anti-U1RNP antibodies. Anti-NDNA, anticardiolipin antibodies, antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor may also be present. Anti-Sm antibody, highly specific for systemic lupus erythematosus, is not found in NLE. The maternal antibody titer is usually higher than the infant titer. In apparently seronegative infants, more sensitive studies such as ELISA, immunoblotting, or line immunoassay, should be used instead of immunodiffusion techniques. Skin biopsy, which is usually not necessary for diagnosis, shows changes characteristic of lupus erythematosus, i.e., epidermal atrophy, vacuolization of the basal layer with a sparse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction with a periappendageal distribution. In many instances, histopathological features in children with NLE rash are subtle. Direct immunofluorescence is positive in 50% of cases, demonstrating granular deposits of IgG, C3, and IgM at the dermoepidermal junction.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis encompasses congenital infections including rubella, cytomegalovirus and syphilis, congenital graft-versus-host disease, annular erythema of infancy, tinea corporis, and seborrheic dermatitis. False-positive VDRL tests for syphilis may occur in NLE. Telangiectasia and photosensitivity may suggest Bloom syndrome or Rothmund–Thomson syndrome. Serologic studies for autoantibodies in both infant and mother help to confirm the diagnosis. Skin biopsy for histologic and direct immunofluorescence studies is seldom necessary.

Course, management, treatment, and prognosis

Neonates with suspected NLE should receive a complete physical examination, electrocardiogram, complete blood count with platelet count, and liver function tests (Box 20.1).

Skin lesions are transient. Treatment of skin disease consists of sun protection and the application of topical steroids. Pulsed dye laser therapy may be considered for residual telangiectasia. Congenital heart block is permanent. Half of newborns with complete congenital heart block require implantation of a pacemaker in the neonatal period.30,64,72 The average mortality rate from complete congenital heart block in the neonatal period is 15%; another 10–20% die of pacemaker complications.25,30 Late-onset cardiomyopathy may develop in a few infants.73–75

Mothers with anti-Ro or anti-La antibodies have a risk of delivering an infant with NLE in the range of 1–20%, depending on whether they have asymptomatic or symptomatic SLE.27,30 The risk of recurrence of congenital heart block in subsequent pregnancies may be as high as 25%.64 Such pregnancies should be closely monitored, ideally by obstetricians familiar with managing high-risk pregnancies. Although NLE is usually self-limited, SLE or other rheumatologic/autoimmune diseases may develop later in life in a small subset of patients.65,76,77 The exact risk is unknown.

Other collagen vascular disorders of the newborn and young infant

Collagen vascular disorders seldom appear in newborns and young infants. Both discoid and systemic lupus erythematosus (LE) has been reported in infants below 12 months of age, but skin lesions are very unusual.78–81 A systemic LE-like rash was seen at 12 months of age in an infant with C1q deficiency.82 Patients with familial chilblain lupus have been reported to develop skin lesions in infancy. Familial chilblain lupus is usually due to mutations in the TREX1 gene, and thus is allelic with the Aicardi–Goutières syndrome (AGS).83 In AGS, chilblains are a common symptom, and there is some overlap between AGS and familial chilblain lupus. In one family, a dominant heterozygous mutation in SAMHD1 caused familial chilblain lupus with infantile onset.84

Localized (linear) morphea can be present at birth, but this is very rare.85 It may be initially confused with vascular malformations such as port-wine stains.

Drug eruptions

Cutaneous drug reactions86,87 are very rare in neonates. This is likely due to the relative inability to generate a drug-induced immune response88–90 and the lack of medication exposures together with time lag for sensitization required in many drug hypersensitivities. However, drug eruptions become far more common in older infants. These eruptions may be true hypersensitivity reactions, but many are idiosyncratic reactions, triggered in the setting of concomitant viral illnesses. If a drug eruption is suspected, a detailed history of medications should be obtained. In breast-feeding infants, this should include medications taken by the mother. A history of recent vaccinations can also be relevant.

Maculopapular and morbilliform eruptions are the most frequent type of drug reactions in infants and usually have a benign course (Fig. 20.7). These eruptions are characterized by the abrupt onset of multiple small pink-red macules and papules that begin on the head and upper trunk and symmetrically progress downwards (Figs 20.8, 20.9). The lesions appear within the first 2 weeks of starting the offending medication and are often pruriginous. Most benign drug reactions are delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions to antibiotics.91 Distinguishing a drug eruption from a viral exanthem is often difficult. Skin biopsy is not helpful in most cases. It has been proposed that FAS ligand serum concentration might be useful in discriminating between drug rashes and viral exanthems, as it is raised in drug reactions and consistently low in viral rashes,92 but it is not available in most clinical settings. Drug eruptions are usually self-limiting after prompt recognition and discontinuation of the causative drug. Antihistamines in infants older than 6 months of age may help to alleviate the pruritus, but systemic steroids are not indicated unless the reaction is severe, and their efficacy remains controversial. Drug rechallenge to confirm the diagnosis is not recommended,91 and family education about generic and trade drug names is important to avoid recurrences.

The primary infection by Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), usually asymptomatic in young children, may display the so-called ‘ampicillin rash’ when patients are given ampicillin, amoxicillin or, much less frequently, other antibiotics such cephalosporins or macrolides. The incidence of ampicillin rash in EBV infection was estimated to appear in 90% of patients, but recent studies have shown that the amoxicillin-induced rash appears only in about 30% of cases.93 The antibiotic-related rash can be macular, petechial, scarlatiniform or urticarial, and it can be differentiated from the spontaneous eruption in EBV infection in that it begins 1–2 days after starting the antibiotic treatment and that it is more severe and generalized, involving the head, neck, trunk, extremities, and even palms and soles. No consistent relationship has been shown for antibiotic dose, duration of treatment, atopic history, or previous exposure to penicillin. The pathogenesis behind the aminopenicillin-associated rash is uncertain. Ampicillin and amoxicillin can be re-administered after viral resolution without any adverse effect, suggesting a toxic etiology and not a true allergy.93,94

Vancomycin, an antibiotic frequently administered to premature newborn infants for Staphylococcus epidermidis nosocomial infections, may produce shock and rash (red-baby syndrome).95,96 This reaction is characterized by the appearance of an intense, macular, erythematous eruption on the neck, face, and upper trunk shortly after the infusion is completed. It may be accompanied by hypotension and shock. The reaction resolves rapidly in a matter of hours. It is frequently associated with rapid infusion; however, lengthening the infusion to more than 1 hour does not completely eliminate the risk.

Newborns with AIDS have an increased susceptibility to drug reactions.97,98 Reactions to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole in patients with HIV infections can be severe and life-threatening.99

Fixed drug eruptions (FDE) are rare in infants and newborns. The classic cutaneous reaction of FDE consists of one or more round, well-circumscribed, erythematous to violaceous patches of variable size that appear anywhere on the body. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxasole and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are well-known causes of fixed drug eruptions. Reactions of the scrotum and penis, with erythema and edema resulting from hydroxyzine hydrochloride, have also been described in early infancy,100 as well as bullous forms.101 Recurrences in the exact same location are common prior to diagnosis.

Vegetant bromoderma is a reaction to bromides characterized by coalescing papules and pustules which form vegetant inflammatory or pseudotumoral lesions. It usually affects the scalp, face, and legs. Most cases of vegetant bromoderma have been described in infants after the ingestion of syrups and solutions containing bromide, which has sedative, anticonvulsant and expectorant properties, or the spasmolytic agent scopolamine bromide.102,103 The eruption ceases after withdrawal of bromide. The risk of systemic intoxication, known as bromism, makes it advisable to avoid bromide use in newborns and infants.

Other anecdotal reports of toxicoderma in very young infants or newborns have been described, such as a papular eruption from G-CASF for collection of stem cells,104 a lichenoid reaction to ursodeoxycholic acid for neonatal hepatitis,105 and a maculopapular rash from diazoxide used for neonatal hyperglycemia (Fig. 20.9).106

Serum sickness-like reaction is rare in neonates but has been reported in infants as young as 5 months of age.107 It is characterized by fever, an urticarial eruption, and arthralgias. Lymphadenopathy may be present. In contrast to true serum sickness, there are no immune complexes, vasculitis, or renal impairment. The most commonly implicated drug has been cefaclor,107–109 but this eruption can be seen in infants with an unknown or presumably viral etiology (Fig. 20.10).

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is characterized by acute onset of fever and a widespread eruption of less than 5 mm sterile pustules on an erythematous background (Fig. 20.11). It is more common in older children and adults, but a few cases have been reported in infancy.110,111 Known etiologies of AGEP include exposure to systemic medications, mainly antibiotics, recent viral infection, vaccinations,111 and exposure to mercury.112 Histological study shows subcorneal pustules associated with dermal edema, and occasionally vasculitis, eosinophils in the superficial dermis, and focal keratinocyte necrosis. AGEP may be both clinically and histologically difficult to distinguish from pustular psoriasis. In AGEP, however, additional skin lesions such as purpura, vesicles, bullae, and target lesions, may be seen,111,112 there is an antecedent drug exposure in most cases, and the fever and pustules have a shorter duration than in pustular psoriasis. The condition fades away in a few days to weeks after abandoning the offending medication.

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome

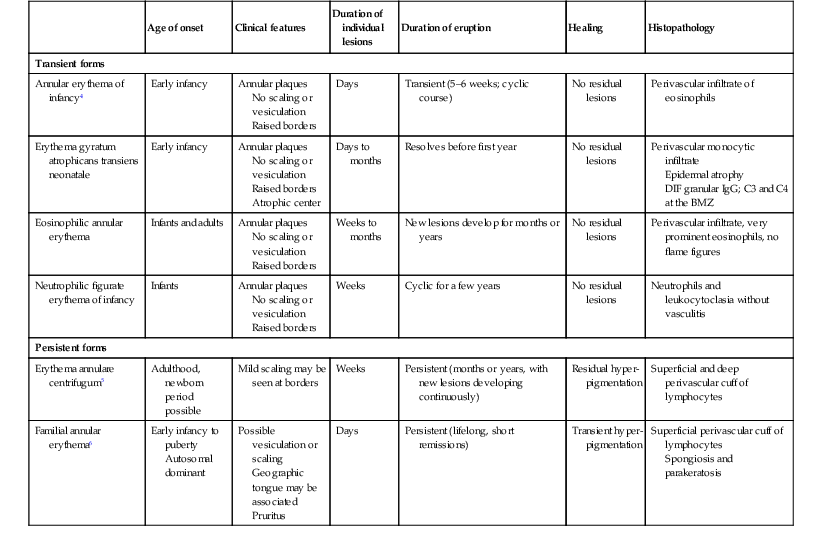

Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DISH), also known as ‘drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms’ (DRESS) is a serious drug reaction characterized by fever, skin rash, lymphadenopathy, hematological abnormalities and internal organ involvement, especially involving the liver.113–115 It is rare in this age group, although a fatal case in a 3-month-old infant has been reported, as well as a case in a premature infant,116,117 and another in a 22-month-old patient.118 The most commonly implicated drugs are anticonvulsants, particularly phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine, and antibiotics, e.g., trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, isoniazid, vancomycin, and amoxicillin.119 It usually occurs within 2 months of the introduction of the offending drug, most often in 2–6 weeks, but cases developing after 3 months of exposure have also been reported.120 However, symptoms can appear earlier and be more severe after re-exposure. The condition may be progressive even after discontinuation of the causative agent. Affected patients are frequently initially misdiagnosed as having less severe conditions such as streptococcal pharyngitis, mononucleosis, or other viral illness, both because the association with medication is not recognized and because early cutaneous manifestations are nonspecific maculopapular rashes. Facial and periorbital swelling are very characteristic and suggestive of DRESS. Diffuse erythroderma, desquamation and occasionally vesicles and bullae evolving into Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis may occur (Table 20.2).121 Erythema multiforme-like targetoid lesions and features mimicking Kawasaki disease (KD) have been reported.119,122 In addition to the nearly universal fever, rash and lymphadenopathy, laboratory abnormalities are common, namely eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis and elevated transaminases. Lungs, kidneys, muscle, and the gastrointestinal system may also be affected.123 Thyroid disease has been reported in 6–10% of pediatric patients.120,123 Systemic steroids are the most commonly used therapy,113,114,123 and successful treatment with intravenous immunoglobulins in refractory-to-steroid cases has also been reported.124 Although the prognosis is generally good, the condition is potentially life-threatening and early diagnosis and discontinuation of the offending drug are very important. In cases of severe cutaneous or systemic involvement, admission to an ICU or a burn unit for careful monitoring is mandatory (Box 20.2).125

TABLE 20.2

Characteristic findings of severe cutaneous drug reactions

| DRESS | SJS/TEN | AGEP | |

| Onset of eruption | 2–6 weeks | 1–3 weeks | 48 h |

| Duration of eruption (weeks) | Several | 1–3 | <1 |

| Fever | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Mucocutaneous features | Facial edema, morbilliform eruption, pustules, exfoliative dermatitis, tense bullae, and possible target lesions | Bullae, atypical target lesions, and mucocutaneous erosions | Facial edema, pustules, tense bullae, possible target lesions, and possible mucosal involvement |

| Histological pattern of skin | Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate | Epidermal necrosis | Subcorneal pustules |

| Lymph node enlargement | +++ | − | + |

| Hepatitis | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Other organ involvement | Interstitial nephritis, pneumonitis, myocarditis, and thyroiditis | Tubular nephritis and tracheobronchial necrosis | Possible |

| Neutrophils | ↑ | ↓ | ↑↑↑ |

| Eosinophils | ↑↑↑ | − | ↑ |

| Neutrophils | ↑ | ↓ | ↑↑↑ |

| Mortality rate | 10% | 5–35% | 5% |

AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Modified from Husain Z, Reddy BY, Schwartz RA. DRESS syndrome: Part II. Management and therapeutics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013; 68(5):709.e1–e9.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are characterized by detachment of epidermis, acute skin blisters, and mucous membrane erosions, and are generally considered to be on a spectrum of the same disease. SJS is defined as epidermal detachment of <10% body surface area (BSA), TEN as >30% BSA involvement, and cases with 10–30% BSA classified as SJS/TEN overlap.126 All forms are extremely rare in newborns and very infrequent in infants.

Cutaneous findings

Cutaneous involvement is widespread but usually involves the trunk and consists of flat targetoid lesions with two zones of erythema or ill-defined confluent flat erythematous to purpuric macules.127 Underlying erythema and blisters may be seen in both presentations (see Fig. 10.34![]() ). Mucosal erosions are reported to be present in more than 90% of patients, and a majority have two or more affected membranes127,128 with oral and conjunctival mucosa most commonly affected, and less frequently genital, anal, pharyngeal, and upper respiratory tract involvement developing (Fig. 20.12; Box 20.1). Numerous reports have described patients with ‘atypical SJS’ who were infected with Mycoplasma pneumoniae and presented with severe mucositis without skin lesions.129

). Mucosal erosions are reported to be present in more than 90% of patients, and a majority have two or more affected membranes127,128 with oral and conjunctival mucosa most commonly affected, and less frequently genital, anal, pharyngeal, and upper respiratory tract involvement developing (Fig. 20.12; Box 20.1). Numerous reports have described patients with ‘atypical SJS’ who were infected with Mycoplasma pneumoniae and presented with severe mucositis without skin lesions.129

Extracutaneous findings

SJS and TEN patients are febrile with malaise and constitutional symptoms. In cases of extensive involvement, an elevated sedimentation rate, leukocytosis, and mild elevation of transaminases may be seen, as well as eosinophilia in drug-related cases. Electrolyte imbalance and hypoproteinemia may be encountered in SJS.

Etiology and pathogenesis

Both SJS and TEN are considered to be immune-mediated mucocutaneous reactions, usually secondary to medications or infections. Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection is a well-documented cause.130,131 In children, the majority of cases are triggered by anticonvulsants, sulfonamides, and oxicam nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.132,133 Cases of TEN in newborns due to E. coli sepsis have been reported; other cases have been related to antibiotics and phenobarbital.134 The greatest risk of development of SJS occurs during 7–21 days after a medication has been started.132 Other reported triggers of SJS include immunizations and viral infections, and as an acute manifestation of graft-versus-host disease in infants with severe combined immunodeficiency or after bone-marrow transplantation.135

Histopathology

Skin biopsy reveals a superficial perivascular mixed infiltrate with vacuolar interface change and apoptotic keratinocytes progressing to full-thickness epidermal necrosis in TEN.

Differential diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis in cases with severe mucosal involvement is erythema multiforme (EM), which is most often triggered by herpes simplex virus infection (see below).126,128,136 Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) can also resemble SJS, particularly early SJS, but the lack of intraoral involvement and level of blistering are helpful clues to differentiate the two conditions.

Treatment

SJS and TEN are potentially life-threatening conditions and their clinical course is typically prolonged, even after drug discontinuation. There is no evidence-based standardized treatment other than supportive care (Box 20.2). Therapies such as systemic corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin, alone or in combination,137–139 are often used but are controversial.140 Recurrences have been reported in up to 20% of patients, a high rate that strongly suggests a potential genetic predisposition.139 Such mechanisms have been shown in Asian patients with the HLA-B*1502 genotype, who have a strong tendency to develop carbamazepine-induced SJS.141 Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced SJS has a better prognosis than its drug-induced counterpart.128,130 Long-term sequelae due to genital and ocular scarring may impact the long-term prognosis.128,139

Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an acute, self-limited disorder of skin and mucous membranes.142–144 It was previously classified as EM minor and EM major, depending on whether there was one or more mucous membranes involved respectively, and the term EM major was often used synonymously with SJS. However, there is now evidence that EM and the spectrum of SJS/TEN have distinct clinical features and different precipitating factors, so the terms ‘EM major’ and ‘EM minor’ are best avoided.127,145 EM is a common disease in children but extremely unusual in the neonatal period and rarely occurs during infancy.97,143,146–151

Cutaneous findings

The prototypic lesion of EM is a 1–3 cm targetoid lesion with a dusky vesicular, purpuric, or necrotic center surrounded by a raised edematous ring of pallor and an erythematous outer ring. In some cases, only two zones are seen, with a single ring around the central papule (atypical target lesions). The lesions are distributed symmetrically on the extensor surface of the extremities and acral parts of the body (Fig. 20.13). They may extend to the trunk, flexural surfaces, palms, and soles. In children, lesions on the face and ears are common, but are rare on the scalp.152 Areas of epidermal detachment may occur, but usually affect less than 10% of the body surface area. Mucosal lesions may occur in EM but are usually milder that in SJS.

Extracutaneous findings

Mild, nonspecific, prodromal symptoms of cough, rhinitis, and low-grade fever are occasionally present in EM.

Etiology and pathogenesis

EM has been considered a hypersensitivity reaction to multiple precipitating factors such as infectious agents, medications, or even severe contact dermatitis. In children, herpes simplex infections are thought to be responsible for more than 80% of EM, although clinical infection may be minor or inapparent.153 HSV-associated EM follows the lesions of herpes by 1–3 weeks. It can recur but not necessarily with every episode of HSV infection. HSV-specific DNA has been detected by polymerase chain reaction and in situ hybridization in lesional skin from children with EM, whether ‘idiopathic’ or clearly HSV-related.153 Cow’s milk intolerance has been described as a cause of erythema multiforme in a neonate.148 Vaccinations were the only known possible causative agents in a newborn and two infants with erythema multiforme.150,154

Laboratory tests and histopathology

The diagnosis is generally made clinically. Histopathologic examination of early lesions reveals a lymphocytic band-like infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction, with exocytosis and individual necrotic keratinocytes in close proximity to lymphocytes (‘satellite cell necrosis’). There is vacuolization of the basal layer with focal cleft formation at the dermoepidermal junction. The upper dermis is edematous. Over time, more extensive confluent necrosis of the epidermis supervenes, resulting in subepidermal blister formation.

Differential diagnosis

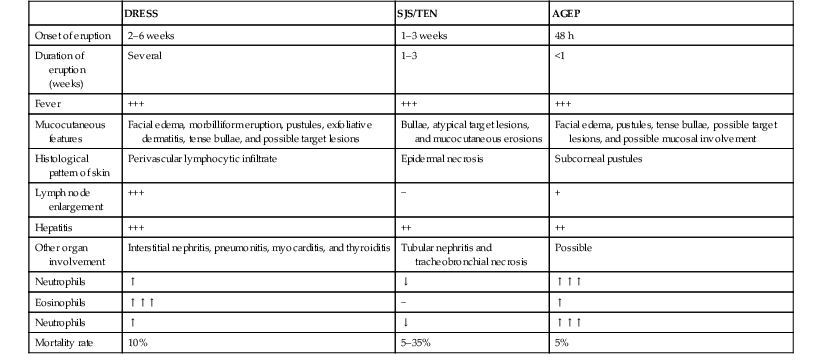

The most common mimic of EM is urticarial multiforme or serum sickness-like reactions (see below). Others include urticarial vasculitis, acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy, Kawasaki disease, EM-like drug eruptions, and Stevens–Johnson syndrome (Table 20.3).

TABLE 20.3

Differential diagnosis of erythema multiforme and STS/TEN

| Erythema multiforme | SJS/TEN | |

| Lesion morphology | Raised three-zone targets | Flat atypical two-zone targets and macules |

| Mucosal involvement | Milder | More severe |

| Percent epidermal detachment | <10% | 10–30% |

| Distribution | Acral and extremities | Widespread and truncal |

| Underlying erythema | Localized | Diffuse |

| Underlying disease | Uncommon | Common |

| Recurrences | Common | Uncommon |

| Etiology | HSV or other infections, rarely drugs | Drugs (less commonly secondary to infection) |

Course, management, treatment, and prognosis

Erythema multiforme is usually self-limited. Individual lesions heal in 1–2 weeks, with residual hyperpigmentation. Conservative supportive care is the preferred form of treatment. Possible underlying causes should be sought and treated. Corticosteroids are usually unnecessary and may even worsen a concurrent infection.155,156 In HSV-associated EM, early intervention or even prophylactic treatment with oral acyclovir may be beneficial.157

Urticaria and urticarial eruptions

Urticaria (hives) and urticarial lesions (other conditions with hive-like morphology) occur frequently in childhood but are uncommon in children younger than 6 months and even rarer in the neonatal period.86,158–167

Urticaria is defined by the development of transient edematous pruritic wheals (Fig. 20.14). By definition, individual lesions last less than 24 hours. Hives may occur on the skin and mucous membranes. Urticaria is usually sporadic; however, familial forms with autosomal dominant inheritance have been described for certain forms of urticaria including many of the physical urticarias, such as dermographism, heat urticaria, cold urticaria, vibratory urticaria, and familial hereditary angioedema.

Urticaria and urticarial eruption may be seen in different clinical situations and can be classified in acute and chronic urticaria, physical urticarias and urticarial eruptions with systemic symptoms or in the context of a systemic or autoinflammatory disease depending on disease duration, triggers, associated diseases, and prognosis.

Acute and chronic urticaria

Urticaria can be divided into acute (lasting <6 weeks) and chronic (lasting >6 weeks) types. This division, while somewhat arbitrary, has prognostic and etiopathogenic significance. Chronic urticaria is very rare in infancy and suggests the possibility of an underlying systemic disease.160,168,169

Physical urticarias represent a special subgroup of urticaria in which wheals are elicited by different types of physical stimuli.170 These include dermographic, cold, pressure, cholinergic, aquagenic, vibratory, and solar urticaria.

Cutaneous findings

Urticaria is characterized by transient pruritic wheals that in younger children, may have certain characteristic features. Itching may be absent and may be replaced by pain in this age group. The hives tend to coalesce, forming bizarre polycyclic, serpiginous, or annular shapes (figurative urticaria, Fig. 20.15; or annular urticaria, Fig. 20.16), and may become hemorrhagic.158,161 The term ‘urticaria multiforme’ has been coined to describe this form of annular urticaria, as it is often confused with erythema multiforme, especially in cases where there is an ecchymotic dusky center.171 Sometimes there may be purpura or ecchymosis in urticaria multiforme and the term ‘hemorrhagic urticaria’ has been coined for this. In these cases, the purpura persists longer than 24 hours but the erythematous edematous plaques change from area to area. These features confer a very dramatic appearance to the eruption.

Urticaria multiforme may be also confused with serum sickness-like reaction because there is often associated facial, hand, and feet edema (angioedema). However, in serum sickness-like reaction, often triggered by antibiotics, there may be accompanying fever and arthralgias.

Extracutaneous findings

Acute urticaria may be accompanied by signs of anaphylactic shock. Urticaria may have associated angioedema with a deep swelling of the face, extremities and genitalia, as well as abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, respiratory compromise, and joint pain. Chronic urticaria in children may be the first presenting sign or be seen in autoimmune disorders such as thyroid autoimmunity, systemic lupus, or juvenile arthritis.

Etiology and pathogenesis

In conventional urticaria, hives develop as a result of an increased permeability of capillaries and small venules, which leads to leakage of fluid into the extravascular space.86,162 Mast cell activation leads to release of mediators, such as histamine, that are responsible for these changes. Many triggers (secretagogues) initiate mast cell degranulation through receptors on mast cell membranes, either via an IgE-dependent mechanism or through complement activation (immunologic secretagogues), or by acting directly without the need for receptors (nonimmunologic secretagogues).

The most common provocative agents of acute urticaria in children are infections, drugs, and foods, which account for 40% of the cases of acute urticaria.161,164,166 In the majority of cases of urticaria in children, there is a history of upper respiratory tract infection, otitis media or viral symptoms preceding the onset and many infectious agents have been reported, including mycoplasma, group A Streptococcus, adenovirus, herpes virus type 6, parvovirus, Helicobacter pylori, and others.167 However, exhaustive diagnostic evaluations for an infectious etiology are generally not helpful unless directed by other signs or symptoms. Antibiotics (penicillins, macrolides, and oral cephalosporins), anticonvulsants and NSAIDs are the most frequently incriminated drugs. In IgE, mediated food allergy hives usually appear within minutes to 2 hours after ingestion, and respiratory, gastrointestinal and/or cardiovascular signs and symptoms may also be present. In infants, cow’s milk is the most common food for food-induced urticaria and anaphylaxis. Urticaria may be more common and recurrent in atopic patients.161,164

Identifying the cause of chronic urticaria is even more difficult as it is often idiopathic. Occult infections should be considered (such as a low-grade urinary tract infection or otitis), as well as autoimmune disorders. Thyroid autoimmunity, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes, and coeliac disease have been associated with chronic urticaria in children, but not in infants.169

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of urticaria is usually made clinically. In atypical or chronic cases, skin biopsy may be helpful, particularly if persistent or if prominent systemic symptoms are present. Histopathologic examination demonstrates vascular dilation, edema, and a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate most typically composed of lymphohistiocytic cells, polymorphonuclear cells, and eosinophils. The presence of neutrophils, particularly if predominant, can be an important clue to an autoinflammatory disease, which requires different evaluation and management (see below).

In most cases, laboratory tests are not usually necessary to evaluate acute urticaria, unless signs point to a specific infection. An exhaustive search for an underlying cause not elicited by history alone is unwarranted. In drug-induced urticaria, the eosinophil count may be elevated. In cases with recurring episodes, it may be useful to keep a diary of triggering factors. In many patients, no cause is identified. For chronic urticaria the same principles apply and investigation of thyroid autoimmunity, celiac disease and other autoimmune conditions may be considered if suggested by the patient’s history or signs.

Differential diagnosis

Urticaria in infants is often misdiagnosed as erythema multiforme, acute hemorrhagic edema and other forms of vasculitis, annular erythema of infancy, Kawasaki disease, or serum sickness. In neonates, generalized hive-like eruptions and dermatographism can also be seen in diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis (see Chapter 28).172 Hemorrhagic urticaria and annular urticaria especially may be mistaken for erythema multiforme because the dusky center gives a targetoid configuration (Table 20.4). However in urticaria, there are no epidermal changes, blistering, or necrotic centers. Autoinflammatory conditions should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of neonates with urticaria, especially in febrile infants (see below).

TABLE 20.4

Differential diagnosis of urticaria multiforme and erythema multiforme

| Skin lesions | Duration of individual lesions | Mucous membranes | Angioedema (face and extremities) | Dermographism | Pruritus | Triggers | Treatment | |

| Urticaria multiforme | Annular and polycyclic wheals with central clearing | 24–36 h, no fixed lesions. No residual pigmentation |

Swollen lips and mucosal edema may be present without erosions | May be present | May be present | Present | Viral infections, drugs, idiopathic | Discontinue any new or unnecessary medications; antihistamines; systemic steroids can be helpful in more recalcitrant cases |

| Erythema multiforme | Annular and polycyclic papules and plaques with necrotic, vesicular or dark center, middle ring of pallor and edema, outer ring of erythema or blisters | 7–10 days, fixed lesions. Residual pigmentation |

Blisters and erosions may be present | Not present | Not present | Usually mild | Herpes virus, mycoplasma | Supportive care; early institution of systemic steroids can sometimes be helpful |

Adapted from Shah KN, Honig PJ, Yan AC. ‘Urticaria multiforme’: a case series and review of acute annular urticarial hypersensitivity syndromes in children. Pediatrics 2007 May; 119(5):e1177–83.

Course, management, treatment, and prognosis

Acute urticaria in infants is usually benign and self-limiting. If medication is required, oral antihistamines are the mainstay of therapy. First generation antihistamines are safe in older infants, however, in newborns who have an increased susceptibility to antimuscarinic side-effects, they may cause central nervous system (CNS) excitation, which in rare cases can lead to seizures. Second generation antihistamines such as cetirizine and levocetirizine have been proved to be safe in infants older than 6 months.173,174 Systemic corticosteroids are rarely necessary.

Physical urticarias

Physical urticarias represent a subset of urticaria triggered by physical agents. These include cold, cholinergic (heat), solar, dermographic, delayed-pressure, and vibratory urticaria. Physical urticarias are often chronic. Dermographism is the most common type.

Dermographism is manifested by the appearance of linear wheals at the sites of rubbing or scratching of the skin. Wheals usually fade in a few minutes. It is the most common form of physical urticaria in young children and in many cases of ordinary acute and chronic urticaria, there is some degree of dermographism. In neonates, dermographism can also be a manifestation of ‘silent’ diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis.172

In pressure urticaria, deep painful wheals develop at sites of the pressure. The onset of the urticarial lesions may be delayed for a few hours after the pressure.

Cholinergic urticaria is characterized by discrete, small, papular wheals elicited by heat, stress, or physical activity. Aquagenic urticaria is considered a variant of cholinergic urticaria triggered by contact with water or perspiration independent of temperature. Both are usually seen in adolescents and adults.

Acquired cold urticaria is triggered by contact with cold objects, water or air. It is the most severe form of all the physical urticarias, as it may be associated with angioedema, hypotension and syncope. Acquired cold urticaria may be primary or secondary to cryoglobulinemia or a viral infection.

Familial forms with autosomal dominant inheritance have been described for dermographic, vibratory, cholinergic, and cold urticaria.175–177 Although rare, these familial cases begin early in life, even immediately after birth, and have a lifelong course, usually with increased severity. Familial cold urticaria is discussed below within the autoinflammatory syndromes.178

Urticarial eruptions associated with autoimmune disorders or autoinflammatory diseases

Autoimmune diseases such as thyroid autoimmunity, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, type 1 diabetes, and coeliac disease have been associated with chronic urticaria but this is extremely unusual in infants. In many cases, there are other symptoms and signs that point to the correct diagnosis.

In neonates and infants, urticarial eruptions, especially if persistent, can be the first manifestation of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) such as NOMID and familial cold urticaria. In NOMID, the urticarial eruption is usually not pruritic, is very persistent, and often there is associated fever. The other symptoms of NOMID such as arthropathy and neurologic symptoms develop soon after. Familial cold urticaria may present in infancy or early childhood with urticaria induced by cold exposure but characteristically there is delayed onset after exposure. Fever and arthralgia are often present.

Isolated angioedema

Angioedema is characterized by subcutaneous edema, with diffuse swelling of the eyelids, genitalia, lips, and tongue. Angioedema is most commonly seen accompanying acute and chronic urticaria. Isolated angioedema without urticarial skin lesions is infrequent and very rare in infants. Angioedema is often idiopathic, but may represent a hypersensitivity reaction to different agents or a manifestation of hereditary angioedema. This autosomal dominant disorder is due to lack (type I) or disfunction (type II) of C1-inhibitor. There is a third hereditary form with normal C1 inhibitor levels. In hereditary angioedema, there are recurrent episodes of painful and persistent (24–72 h) swellings on the face and extremities. Gastrointestinal and respiratory tract involvement may occur with severe abdominal pain and life-threatening upper airway obstruction. Onset is usually during late childhood or adolescence. There are rare reports of initial episodes of angioedema in the perinatal period.179

Diagnosis of isolated angioedema should prompt obtaining C4 levels (the natural substrate for C1 esterase) and C1 inhibitors (antigenic and functional levels).

Autoinflammatory syndromes

Autoinflammatory syndromes refer to a group of diseases in which recurrent systemic inflammation is triggered, often by minor infections, cold temperature, or other innocuous stimuli. Unlike autoimmune diseases, affected patients do not make antigen-specific autoantibodies.180 Many of these are genetic disorders due to mutations in genes that alter the innate immune system (Box 20.3).181,182 Several present in the neonatal period or infancy with prominent skin findings.

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS)

Three allelic diseases: familial cold urticaria (also called familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome, FCAS); Muckle–Wells syndrome, and chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome (CINCA) (also known as neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID)) are now grouped under the umbrella term ‘cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes’ (CAPS). They are the result of activating mutations in the CIAS1 gene, which codifies a protein called NALP3, NLRP3, or cryopyrin. This protein is a key component in the NALP3 inflammasome. Its constitutive activation leads to continuous caspase activation, which leads to an increased conversion of pro-IL-1β into IL-1β, resulting in multisystem disease.

Familial cold urticaria

Familial cold urticaria (FCU) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by the development of burning wheals, and frequently pain and swelling of joints, stiffness, chills, and even fever after exposure to cold, especially in combination with damp and windy weather.183–186 The skin lesions appear on exposed areas and generalize afterwards. Leukocytosis may be present during the attacks. The reaction may be delayed for up to 6 hours after cold challenge. In contrast to acquired cold urticaria, the reaction cannot be elicited by an icecube test; rather, the patient must be subjected to cold environmental temperatures or cold water immersion. On skin biopsy, a neutrophilic infiltrate predominates. The symptoms tend to improve with age. Responses to H1 and H2 blockers and ketotifen are poor. Stanozolol has been of limited benefit.187 FCU has also been described along with amyloidosis and deafness as Muckle–Wells syndrome (MWS).188 It has been recently demonstrated that both FCU and MWS are due to mutations in the CIAS1 (cryopyrin) gene; in fact they are the same disorder and may share exactly the same genetic mutation.189 FCU and MWS are also allelic diseases with CINCA syndrome (see below), which is also due to CIAS1 gene mutations.190

Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome (CINCA)

CINCA syndrome,191–194 also known as neonatal onset multisystemic inflammatory disease (NOMID), is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease of neonatal onset characterized by skin rash, arthropathy, and CNS manifestations. Cutaneous findings are the presenting signs. The disease follows a chronic course with acute febrile exacerbations, lymph node enlargement, and hepatosplenomegaly. Two-thirds of patients are born prematurely.

Cutaneous findings

A skin eruption is usually the first manifestation of the disease and is present at birth or develops during the first 6 months of life. It is characterized by generalized, evanescent, urticarial macules and papules that migrate over the course of a single day and wax and wane in intensity (Fig. 20.17). The rash is typically always present but can worsen with increased disease activity flare-ups. The lesions are usually asymptomatic, but can be pruritic, especially after sun exposure.193,194 Geographic tongue and oral ulcers have been noted in a single patient.194

Extracutaneous findings

Symmetric or asymmetric arthropathy is another constant finding and is severe in half of patients. It is often absent in the first few weeks of life, but usually develops during the first year.193,195 The knees are most frequently affected, followed by the ankles and feet, elbows, wrists, and hands. Neurologic signs and symptoms such as headache, vomiting, and seizures develop at a variable age, and intellectual impairment, spasticity, and hypotonia have been described. Progressive sensorineural hearing loss and hoarseness are also common. Ocular disease, an inconstant finding, may include papilledema, uveitis, keratitis, conjunctivitis, and chorioretinitis. Affected children may have a characteristic phenotype with growth retardation, and an increased head circumference, with frontal bossing. Icterus may be present in the neonatal period, especially in patients with severe arthropathy.193

Etiology and pathogenesis

Mutations in the CIAS1 gene have been identified in 60% of patients with CINCA syndrome.196,197 In a subset of patients in whom the mutation was not detected by standard techniques, molecular cloning has revealed somatic CIAS1 mutations.198 CIAS1 encodes a protein called ‘cryopyrin’, which is involved in the regulation of apoptosis and the inflammatory signaling pathway.197 It is proposed that familial cold urticaria and CINCA represent extreme groups of the same disease, defined by the magnitude of phenotypic expression.197 Considerable clinical overlapping exists between these disorders.

Laboratory tests, radiologic findings, and histopathology

Nonspecific findings typical of a chronic inflammatory process include microcytic anemia; leukocytosis with high neutrophil and eosinophil counts; elevated platelet counts; sedimentation rates, and acute-phase reactants; and polyclonal hyperglobulinemia G, A, or M. Rheumatoid factor and antinuclear antibodies are usually absent. Liver enzymes may be mildly elevated. CSF examination shows pleocytosis and high protein levels.

Radiologic studies of the affected joints show irregularly enlarged, bizarre, spiculated epiphyses with a grossly coarsened trabecular appearance.193,195 There is periosteal new bone formation, and growth cartilage abnormalities are frequent. With time, there is bowing deformity of long bones and shortening of diaphyseal length. CT scans of the head have demonstrated hydrocephalus and cerebral atrophy.

Histopathologic examination of the skin reveals interstitial and perivascular neutrophilia.194,195 Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis has been described.194 Biopsies of lymph nodes, liver, and synovium show nonspecific signs of chronic inflammation.

Differential diagnosis

CINCA must be differentiated from systemic onset juvenile arthritis. The main differences are its neonatal onset, persistent rash, the short duration of bouts of fever, absence of morning stiffness, and central nervous system involvement. The arthropathy is more deforming, and the radiographic findings of enlarged and disorganized epiphyses are distinctive. In addition, the response to NSAIDs is poor. Urticaria should also be considered and the predominance of eosinophils in skin biopsy may be a relative clue.

Course, management, treatment, and prognosis

Untreated, the disease follows a chronic course with acute febrile exacerbations and can have a fatal course. Occasionally, it causes death in the first or second decade. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be effective for pain relief but do not alter the course of the disease. Prednisone has been palliative in doses ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 mg/kg per day.195 Chlorambucil and penicillamine have been tried, with limited success.199,200 Thalidomide has shown beneficial effects in a single patient.201 Other choices include methotrexate, the recombinant human IL-1 receptor antagonist anakinra,202–205 and the anti-TNF-α agent etanercept.206 Other IL-blocking agents such as rilonacept and canakinumab, are very effective and promising agents.207

Pustular autoinflammatory syndromes in newborns

Two syndromes, called deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist (DIRA) and deficiency of the IL-36 receptor antagonist (DITRA), can present in the neonatal period in the form of a severe pustular eruption (see Chapters 10 and 16).

In DIRA,208 homozygous mutations in the gene IL1RN lead to complete absence of the IL-1 receptor antagonist, which leads to an imbalanced IL-1 action causing continuous inflammation with neonatal onset. The eruption appears as crops of pustules or generalized severe pustulosis; histopathology shows extensive neutrophilic infiltration of the dermis and the epidermis. In some cases, DIRA closely resembles pustular psoriasis.209 The skin eruption is accompanied by malaise, but not high-grade fevers. Typically, pain and joint swellings, with epiphyseal ballooning, resembling CINCA syndrome, develop very early in life. Treatment with anakinra (the recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist) is rapidly effective. If untreated, patients will develop multiorgan failure and may suffer a fatal outcome.

In some families with autosomal recessive pustular psoriasis, appearing as early as one week of life, homozygous missense mutations in the IL36RN gene, which codifies the IL-36 receptor antagonist, have been reported.210 This disease has been named ‘DITRA’. Patients show a diffuse skin eruption with erythema and pustules and high-grade fever. Unlike DIRA, patients with DITRA seldom have other organs involved except the skin, and the skin flares are associated with high-grade fever. It is possible that deficiencies in the IL-36 receptor antagonist are responsible for cases of classic pustular psoriasis.

Immunoproteasome-related syndromes

CANDLE syndrome, an acronym for chronic, atypical, neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature,211 describes a group of diseases due to homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in genes encoding components of the immunoproteasome, mainly the PSMB8 gene encoding the β5i subunit of the immunoproteasome.212 The proteasome and the immunoproteasome are cell structures involved in peptide and protein destruction and/or processing for presentation to the immune system. Ubiquitinized proteins fated to destruction should be recognized by the proteasome/immunoproteasome and cleaved into smaller peptides. In the absence of a normal proteasome/immunoproteasome function, these proteins accumulate in the macrophages, thus leading to cellular stress; in turn, cellular stress causes activation of the JAK pathway and accumulation of proteins that cannot be destroyed by misfunctioning proteasomes/immunoproteasomes, thus leading to further cellular stress. The end-point in this circle is the release of proinflammatory molecules with a strong interferon signature that leads to the symptoms of the disease.

CANDLE syndrome begins in the first weeks of life in the form of recurrent attacks of erythematous and purpuric plaques and nodules that disappear leaving purpuric residua. They are accompanied by fever. Later in life, the nodules continue to appear, as well as a typical perioral and periocular violaceous swelling. Virtually any organ can be the target of an acute attack of inflammation, which can be fatal. In childhood, a typical lipodystrophy with short stature leads to an unmistakable phenotype. On histopathology, an interstitial infiltrate composed of bizarre mononuclear cells, neutrophils, and leukocytoclasia occupies the dermis and extends into the subcutis.

Two other diseases, called ‘JMP syndrome’ (an acronym for joint contractures, muscle atrophy, microcytic anemia, and panniculitis-induced lipodystrophy) and ‘Nakajo–Nishimura syndrome’ in Japan, are allelic with CANDLE syndrome, and have overlapping manifestations.

There is currently no effective therapy for CANDLE syndrome. NSAIDs, oral corticosteroids and methotrexate can help to control inflammation. No biologic agents, including etanercept, anakinra or canakinumab, have thus far been efficacious.

Eosinophilic cellulitis

Eosinophilic cellulitis or Wells syndrome is a recurrent inflammatory condition, most commonly seen in adults, but cases in infants, and even in newborns213–216 have been reported. The pathogenesis of Wells syndrome is not clearly understood. It may represent a hypersensitivity reaction triggered by insect bites, viral and parasitic infections, thimerosal-containing vaccines, or drugs.213,217–221 However, in approximately one-half of reported pediatric cases, there was no identifiable precipitating factor.222 Patients present with persistent erythematous edematous plaques that resolve spontaneously after 2–8 weeks, leaving residual skin hyperpigmentation (Fig. 20.18). The lesions may occasionally become bullous.213,223–225 Occasionally, systemic manifestations, including fever, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgias can occur. Recurrences are common, with exacerbations and remissions spanning several years. Peripheral eosinophilia is found in up to 50% of cases in an active phase. Biopsy shows diffuse infiltration of eosinophils within the dermis along with characteristic flame figures caused by the deposition of eosinophil major cationic protein. Older lesions may show a granulomatous histiocytic palisade surrounding the flame figures.226 The main differential diagnosis is bacterial cellulitis, which is usually tender, warm, lacks pruritus and responds well to antibiotic therapy. Other much less common differential diagnoses include Churg–Strauss syndrome, eosinophilic fasciitis, eosinophilic folliculitis, and hypereosinophilic syndrome.227–229

Wells syndrome is often self-limited. If a treatable precipitating factor can be identified, improvement with treatment of the underlying condition may occur.221 When needed, treatment with topical and systemic corticosteroid therapy alone or in combination has proved useful.213 In recalcitrant cases, dapsone and antihistamines are treatment options.213,223 Although Wells syndrome is a benign condition, if the child presents with systemic symptoms or a chronic course, defined as >6 months of peripheral eosinophilia or recurrences of clinical disease, referral to hematology/oncology should be considered.213

Eosinophilic annular erythema of infancy is considered by some authors as a variant of Wells syndrome.230,231 Although more common in adults, it has also been reported in infants.7,8,232,233 It is characterized by persistent annular lesions, a chronic course, resistance to treatment and high relapse rate. Histopathology shows a perivascular infiltration of eosinophils but without flame figures or granulomas.

Sweet syndrome

Sweet syndrome, also known as acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis, is a benign disease characterized by tender, raised erythematous plaques, fever, peripheral leukocytosis, histologic findings of a dense dermal infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and a rapid response to systemic corticosteroids.234–238 Only a few pediatric cases have been reported,239–253 the youngest being 5 weeks of age.242 Two brothers with Sweet syndrome starting at 2 weeks of life have been reported.250

Cutaneous findings

The lesions of Sweet syndrome typically have an acute, explosive onset and are characterized by indurated, tender, erythematous plaques, or nodules that vary in size from 0.5 to 4 cm (Fig. 20.19). Pustules may also be present, though usually at a later stage. The borders may be raised, mammillated, or even vesicular. Some lesions may show central clearing, forming annular or gyrate plaques (Fig. 20.20). The lesions are usually multiple and distributed over the face and extremities or, more rarely, the trunk. Pathergy is not uncommon.253 Without treatment, they tend to heal spontaneously within a few months. In some patients, especially children, the lesions heal with areas of secondary cutis laxa, also known as ‘Marshall syndrome’.241,251,254

Extracutaneous findings

A high, spiking fever is characteristic but may be absent in up to 50% of patients.238 Arthralgias or asymmetric arthritis may be associated, and conjunctivitis or iridocyclitis may be seen in one-third of patients.238 Renal involvement manifesting as proteinuria or hematuria, as well as lung involvement with infiltrates visible on chest radiographs, has also been described. Central nervous system involvement may occur in rare instances and manifests as headaches, convulsions, or disturbance of consciousness. Cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis with lymphocyte predominance is usually found in such cases.255 Neonatal lupus erythematosus has been reported to present with a neutrophilic dermatosis in newborns.256

Etiology and pathogenesis

The pathogenesis is unknown. Many of the patients reported have had a preceding respiratory tract infection or elevated anti-streptolysin O titers.238 Of the cases, 10% have been seen in the setting of a variety of hematologic malignancies, particularly acute myeloid and myelomonocytic leukemias.257 Sweet syndrome has also been associated with solid tumors, inflammatory bowel disease, connective tissue diseases, and chronic granulomatous disease, or it may occur as an adverse reaction to drugs,258–260 particularly granulocyte colony-stimulating factor261 or after vaccination.262 Because of these associations and the rapid response to systemic corticosteroids, Sweet syndrome is thought to represent a hypersensitivity reaction to infectious agents or tumoral antigens.

Laboratory tests and histopathology

An elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and peripheral leukocytosis are frequent accompanying abnormalities. Eosinophilia, microcytic anemia, mild elevation of liver enzymes, and urinalysis abnormalities may be present occasionally. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies have been detected in some cases.238 α1-Antitrypsin deficiency has been documented in one case of Marshall syndrome.254

The histopathologic findings are diagnostic.235 There is a dense perivascular infiltrate composed almost entirely of neutrophils. The dermis appears edematous, and subepidermal blisters may form. Spongiosis, exocytosis, and intraepidermal vesiculation may be seen. There is endothelial swelling and nuclear dust, but true vasculitis is characteristically absent.

Differential diagnosis

The lesions of Sweet syndrome may initially resemble those of EM or acute hemorrhagic edema. Lesions on the lower extremities may resemble those of erythema nodosum, but lesions more characteristic of Sweet syndrome are usually present in other locations.

Course, management, treatment, and prognosis

Sweet syndrome itself is a benign disease but may be a marker of malignancy. If left untreated, it resolves spontaneously over weeks to months. However, recurrences are common. Marshall syndrome may have a poorer prognosis, with the development of elastolysis in the lungs or cardiovascular involvement.

Oral corticosteroids are the treatment of choice and usually elicit a prompt response.263 Potassium iodide administration has been successful in a few cases,264 as have colchicine,265 dapsone,266 clofazimine,251 and intravenous immunoglobulin.246

There is considerable clinical and histopathologic overlap between Sweet syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum in infants.

Kawasaki disease

Kawasaki disease is an acute systemic vasculitis involving small and medium-sized muscular arteries, especially the coronary arteries, of young children.267–269 In the past, many cases in very young infants were diagnosed as ‘infantile polyarteritis nodosa’.

Kawasaki disease occurs predominantly in children under 5 years with the peak incidence between 9 and 11 months.270–272 It is infrequent before 6 months of age, but has been reported in younger infants, including neonates.273–275 Boys are affected 1.5 times as often as girls. Kawasaki disease is an endemic disease with epidemic and geographic clustering. There is seasonal predominance in late winter and spring, although this may differ in different countries.276 Familial cases in household contacts have been described.277 The recurrence rate is 3%, with some patients having two or more recurrences.

Cutaneous findings

The skin is involved in virtually all patients. The initial signs are often diffuse erythema and painful induration of the hands and feet.267,278,279

A polymorphous exanthem on the trunk and proximal extremities usually appears within 5 days of onset of fever (Fig. 20.21). The morphology is most often a nonspecific, diffuse maculopapular or morbilliform eruption, but may be urticarial, scarlatiniform, targetoid, or even pustular. Bullous or vesicular eruptions have not been described. The rash involves the perineum in up to two-thirds of cases, with early desquamation, far earlier than that appearing on the fingers and toes (Fig. 20.22).280

Changes in the lips and oral mucosa include erythema, swelling and fissuring of the lips, strawberry tongue, and erythema of the oropharynx. Oral ulcerations and pharyngeal exudates are not seen. Intermittent acrocyanosis as well as peripheral gangrene have been observed in infants younger than 6 months of age.272,281 Inflammatory changes with necrosis at the site of a previous BCG inoculation have also been described.282

Between 1 and 3 weeks after disease onset, the eruption characteristically begins to desquamate beneath the distal nail plates, and peeling may extend to involve the entire palm and sole. Horizontal depressions in the nail plates (Beau’s lines) usually result. A maculopapular eruption may appear in the convalescent phase, that may represent an adverse effect of intravenous γ-globulin (IVIG) therapy, as it appears approximately 10 days after the infusion. It is usually self-limited and does not require specific treatment.283 Plaque-type, guttate, and pustular psoriasis have been described, either during the acute or the convalescent phase of the disease, which supports a superantigen-mediated etiology.284–287

Extracutaneous findings

Fever lasting for at least 5 days is the cardinal and initial feature of the disease.278,279,288,289 It usually begins abruptly and reaches temperatures as high as 39–40°C. Irritability is usually prominent. Other extracutaneous features include nonexudative conjunctival injection, involving mainly the bulbar conjunctivae, anterior uveitis, and cervical lymphadenopathy, which is present in approximately 65% of cases. Enlarged nodes are usually firm, nonfluctuant, slightly tender, unilateral, and confined to the anterior cervical triangle. Cardiac disease is the main cause of long-term morbidity and mortality. The pericardium, myocardium, endocardium, and coronary arteries may all be involved. Without treatment, coronary artery aneurysms develop in 20% of cases, and are most commonly detected 10 days to 4 weeks after onset. Risk factors for the development of coronary aneurysms include age younger than 1 year, male gender, fever for more than 2 weeks, recurrent fever, and delayed treatment. Aneurysms may also develop in systemic medium-sized arteries and result in peripheral gangrene.281

Polyarticular arthritis and arthralgias may occur in the first weeks of the illness, affecting small as well as large joints. Lethargy and other signs of aseptic meningitis may be present. Abdominal symptoms such as vomiting, diarrhea, and pain are common. Respiratory symptoms due to pulmonary nodules, infiltrates, or pleural effusion may also be observed.290–292 Rare findings include testicular swelling, hemophagocytic syndrome,293 transient unilateral peripheral facial nerve palsy, and transient high-frequency sensorineural hearing loss (20–35 dB).294

Etiology and pathogenesis

Epidemiologic and clinical data295,296 suggest that Kawasaki disease has features of infectious disease in an immunologically susceptible host and of an immune-mediated vasculitis. Many infectious etiologic agents have been suggested as a trigger but none has been consistently demonstrated.295 Regardless of the cause, evidence points to a generalized immune activation with production of various proinflammatory cytokines and endothelial cell activation which lead to coronary artery alteration.268

Host genetic determinants play a role in both susceptibility and coronary artery outcome in Kawasaki disease.297 The incidence rate in siblings is 10 times the population incidence.277,298,299 The risk of occurrence in twins is higher than in ordinary siblings. Parents who had Kawasaki disease in childhood are more likely to have affected children, and children with recurrent disease.300

Laboratory tests and histopathology

In the acute phase, laboratory studies show leukocytosis (~15 000/mm3) with a left shift, normochromic normocytic anemia, increased sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, depressed albumin, and elevated IgM and IgE levels. After IVIG treatment, the value of ESR becomes uninterpretable due to increased plasma viscosity.279 In the subacute stage, in the second and third weeks of illness, there is a marked and almost universal thrombocytosis, which returns to normal in 4–8 weeks. Thrombocytopenia is rarely seen in the acute stage and may be a sign of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Plasma lipids are altered in the acute stage, with depressed plasma cholesterol and HDL.301 There may be mild elevation of transaminases and polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia. There may be sterile pyuria with mild proteinuria. Cerebrospinal fluid shows a mononuclear pleocytosis with normal protein and glucose levels. Skin biopsy findings are not specific. There is edema in the papillary dermis, with a mild perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate. Vasculitis of medium and large arteries is observed.

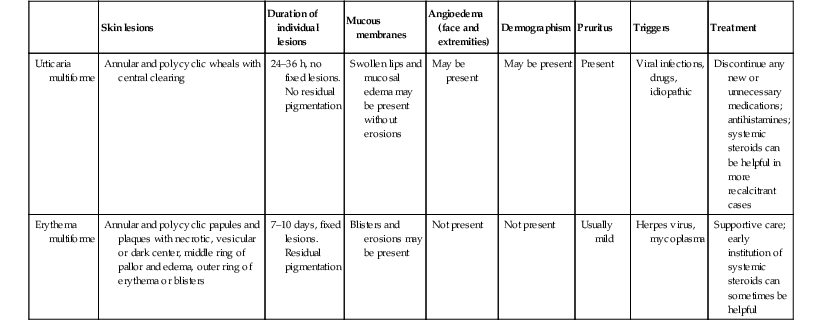

Diagnosis

Kawasaki disease should be suspected267,279 in any patient with fever lasting at least 5 days, nonpurulent conjunctivitis, a polymorphous exanthem, erythema, and swelling of the hands and feet, inflammatory changes of the lips and oral cavity, and acute nonpurulent cervical adenopathy.278,288,302,303