Chapter 8. Immediate care and major incidents

Immediate management of multiple injuries

The management of a patient with multiple injuries depends upon an organized and disciplined approach. The most spectacular injury is seldom the most dangerous while the one that goes unseen can kill the patient. If the ‘ABC’ routine below is followed, life-threatening conditions will be dealt with first and undiagnosed injuries kept to a minimum.

Immediate action

A – Airway.

B – Bleeding.

C – Circulation.

Check the airway

An obstructed airway causes death most rapidly and must be dealt with first. Complete obstruction of the airway is easily recognized but partial obstruction causes a gradually increasing hypoxia which can go unnoticed until the partial pressure of oxygen ( PO 2) falls to critical levels and the patient loses consciousness. Always check the airway.

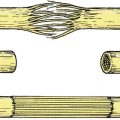

The airway can be obstructed by blood, vomit, broken teeth or dentures, soft tissue swelling around injuries to the neck or larynx, or facial fractures (Fig. 8.1). The first step in resuscitation is to check that the mouth and pharynx are clear (Fig. 8.2).

|

| Fig. 8.1

Obstruction of the airway. The tongue, broken dentures, blood, vomit or a fractured mandible can all obstruct the airway.

|

|

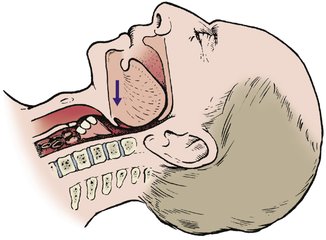

| Fig. 8.2

Consolidation of the right upper lobe after inhalation of a foreign body by an unconscious patient.

|

Respiratory failure can also be caused by chest injuries such as a pneumothorax or flail chest, even if the airway is clear. Pain can also inhibit breathing, and respiratory failure can follow cervical spine fractures above C3 because the phrenic nerve (C3, 4, 5) is damaged, but this complication is so serious that the patients seldom reach hospital. Chest movement and respiratory rate should be checked regularly.

Endotracheal or nasotracheal intubation, or even tracheostomy may be needed to establish an airway.

Stop bleeding

Bleeding is best stopped by external pressure with a thumb or fist over the bleeding point, but a tourniquet may be needed to control bleeding from a limb. Whenever a tourniquet is used, the time of application must be recorded carefully and the tourniquet released after proper control of the haemorrhage has been achieved, or once every hour, to avoid gangrene.

If there is venous bleeding from a limb, lift the bleeding point above the level of the heart. This will stop the bleeding and improve blood pressure.

Restore blood volume

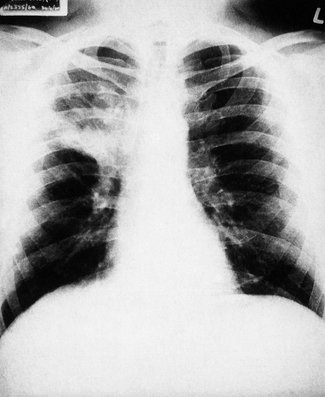

A large intravenous infusion line should be set up as soon as the airway is established and bleeding controlled. Entering a vein is difficult in the deeply shocked or hypovolaemic patient because the vessels will have collapsed. If the usual veins in the forearm cannot be entered, try the cephalic or external jugular. If these cannot be entered either, cut down onto a vein. The long saphenous vein at the ankle is convenient and is reliably found 3 cm above the tip of the medial malleolus and one-third of the way back from the anterior edge of the tibia (Fig. 8.3).

|

| Fig. 8.3

Site for saphenous cut-down. The long saphenous vein lies 3 cm above the medial malleolus, one-third of the way between the anterior and posterior surfaces of the tibia.

|

In a well-organized accident department there will be enough people to do all these things at once while the patient’s clothes are removed – it is better to cut clothing off rather than pull it over limbs that may be fractured.

A skilled resuscitation team can establish an airway, arrest bleeding, remove the patient’s clothes and set up an intravenous line within minutes of the patient entering the resuscitation unit.

Monitoring and complete examination

When these steps have been taken, the resuscitation team is in control of the situation and less immediate problems can be dealt with.

When immediate action is complete:

1. Begin charts.

2. Examine the patient completely.

3. Record ECG.

4. Set up central venous pressure (CVP) line.

5. Check the patient again.

6. Notify appropriate specialists.

7. Grade injury.

Charts

Set up a record of the pulse rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate and neurological signs, including level of consciousness and pupil sizes, as soon as possible.

Complete examination

The entire patient should be inspected for wounds, including the back. If there is any possibility of a spinal injury the patient should be ‘log rolled’, until radiographs are available, to minimize the risk of displacing the fracture. The cervical spine should be protected at all times.

If this thorough inspection is not done very early, injuries will be missed. It is not only embarrassing but reprehensible to save the life of a patient and then find that he cannot work because of a malunited finger that needed only a few turns of adhesive strapping to achieve a perfect result.

Measure the wounds. Bruises and lacerations should be inspected, measured and recorded. Look particularly at the abdominal skin: bruising or imprints of clothing mean that there has been a violent blow to the abdomen and intra-abdominal bleeding should be suspected. Look also for signs of seat-belt bruising.

Examine every bone in the body. This does not take long. The superficial bones, including the skull and clavicle, can be felt with the fingers, the ribs and pelvis ‘sprung’ (p. 24), and long bones stressed. Fingers and toes can be checked by longitudinal pressure and suspicious areas examined radiologically.

Record ECG

ECG leads should be applied, if not done already, and the ECG displayed on a monitor.

CVP line

If there has been severe blood loss, set up a CVP line. The normal CVP is 4–8 cmH 2O and this level should be maintained. In some centres pulmonary capillary wedge pressure is preferred to monitor the restoration of blood volume.

Check the patient again

To be sure that there is no deterioration, check the patient again and again. Pulmonary contusion causing respiratory failure and hypotension from intra-abdominal bleeding may first be apparent at this stage.

Other specialties

If any injuries need specialist attention, the relevant specialists should be informed. Faciomaxillary surgeons, ophthalmic surgeons, neurosurgeons, thoracic surgeons and plastic surgeons may all be needed, as well as ‘general’ surgeons for the management of abdominal injuries.

Advanced trauma life support (ATLS)

Courses on advanced trauma life support are now mandatory for all surgical trainees and not just for those involved in immediate care. The courses teach internationally agreed techniques to a high standard and are very effective.

These courses advise the primary survey and the secondary survey. The primary survey means attending to the airway, breathing and circulation while ensuring no damage is done to the spinal column, etc. The secondary survey involves a full systematic review of all body parts and systems.

Grading

Several systems are used to grade the severity of injury and give a score that can be used to assess the prognosis. Calculate the scores and record them.

First aid at the scene of an accident

There is a tendency for doctors, but especially medical students, to try to save life at the scene of an accident rather than attend to practical matters. In practice, very few accident victims require urgent medical care, and those that do usually need equipment found only in an ambulance or accident department.

If you are the first person at the scene of an accident, with nobody to help, take the following steps:

Check the airway

Check the patient’s airway and clear it if it is obstructed.

Feel the pulse

If the radial pulse cannot be felt, feel for the carotid.

Recovery position

If the patient is unconscious, place them in the recovery position but take special care of the spine if there is any possibility of spinal injury. Protect the cervical spine at all times.

Stop oncoming traffic

Stop traffic before it collides with the crashed vehicle(s) or the patient and send for help from police and ambulance services.

Treat the patient

This done, more time can be spent with the patient. Cover exposed bone with the cleanest material available, arrest bleeding and comfort the patient.

Do not be tempted to pull trapped patients out of cars, unless they are on fire, or start definitive treatment such as reducing fractures. Confirm that the emergency services are on the way, wait for the ambulance and give a clear account of events to the crew.

When the patient is in the ambulance, the first aider’s task is done and it is neither necessary nor desirable to accompany the patient to hospital. Ambulance teams have great experience in dealing with road accidents and know their own equipment and routines well. They do not need help from a stranger, however gifted.

Trapped patients

If a road accident victim is trapped in a car, leave the individual there until the rescue services arrive. Access to the patient will be difficult because the doors of crashed vehicles are usually jammed and to drag an injured patient with broken limbs or a fractured spine through a broken window is only justified if there is a risk of fire. The rescuers should wear stout gloves to protect their own hands from lacerations on broken glass or torn metal.

If the engine compartment has been pushed backwards the patient may have broken legs and be pinned in the car by the steering wheel. The rescue service has the necessary equipment to cut the window pillars and remove the roof of the car to give easy access to the patient (Fig. 8.4). The patient can then be secured to a support placed behind the back and lifted directly into the ambulance, if necessary after intubation and setting up an intravenous line (Fig. 8.5).

|

| Fig. 8.4

Road traffic accident.

|

|

| Fig. 8.5

Emergency rescue. An unconscious patient has an intravenous line and is receiving oxygen before being removed from the vehicle. The roof of the vehicle has been removed for access.

|

Medical rescue team

In many rural areas general practitioners operate accident rescue services to assist the ambulance crew. The general practitioner’s car will have equipment to intubate the patient or set up an intravenous line before the ambulance arrives, and narcotics to provide analgesia while the patient is removed from the wreck.

Major disasters and major incidents

A major disaster is an event which requires an extraordinary mobilization of the emergency services (fire, police, ambulance), and a major incident is one which stretches the resources of the accident department and hospital. Not all major disasters are major incidents. Evacuating families after a flood may not generate even one patient, for example.

Major incident procedure

All accident departments have contingency plans for handling a major incident and carry out regular practice drills. As with the management of multiple injuries, success depends upon a well planned and disciplined approach.

The precise details of major incident routines vary from area to area but a typical plan would be as follows.

Designated hospital

The first people to know of a major incident are usually the police. It is they who initiate the major incident procedure routine and select the hospital to which the casualties will be sent, known as the designated hospital. Although criteria vary from area to area, 15 or more patients likely to require hospital treatment are usually enough to trigger the major incident procedure.

The major incident procedure cannot be instituted by concerned members of the public.

Notifying the hospital

The hospital is notified and the switchboard operators initiate the routine at the hospital, which involves almost every department. The medical records staff, portering staff, mortuary technicians, security staff, administrators and nursing staff all have specific duties, and medical staff are only one part of the team.

Duties of individuals

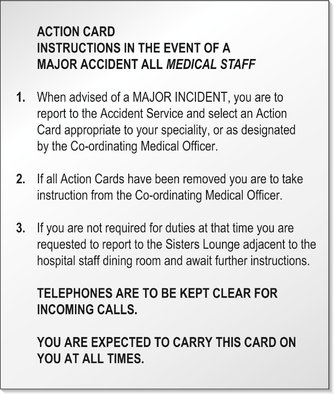

Any member of staff likely to be involved in a major incident will have an action card which lists their duties and they will refer to this when summoned to take part in a major incident routine (Fig. 8.6).

|

| Fig. 8.6

Action card. A typical action card for medical staff who may be involved with a major incident.

By kind permission of Cambridge Health Authority.

|

Some of the duties might be as follows.

Medical Controller. There is always one doctor in charge of coordinating the medical services, usually the consultant in accident and emergency.

The consultant surgeon or consultant physician on call will go to a predetermined ward and create a certain number of beds (perhaps 20) to cope with the anticipated number of victims by discharging or transferring patients well enough to be moved.

The director of the accident service or senior orthopaedic surgeon takes charge of the accident department and allocates staff to other areas, but until then the senior doctor present takes charge. To avoid confusion and conflicting orders, the senior doctor wears a brightly coloured tabard, or sometimes a coloured hat for identification.

Theatre staff. All on-call nurses and operating department assistants go to the operating theatre and await instructions.

Medical records department. All casualties are issued with an emergency record number and a set of case notes. Special sets of records are kept available, with identifying bracelets to attach to the injured patients. In some areas, the recording of injured patients is undertaken by the police.

Medical staff. All available medical staff should go directly to the accident service and place themselves under the direction of the senior doctor. They will usually be given an action card appropriate to their grade.

Medical students. There is seldom any shortage of medical staff during a major incident, and a wealth of untrained individuals such as medical students can be a real handicap. By all means ask if there is anything that can be done but be prepared to do something mundane, such as acting as a runner carrying samples for the laboratory or helping to move patients.

Organization at the hospital

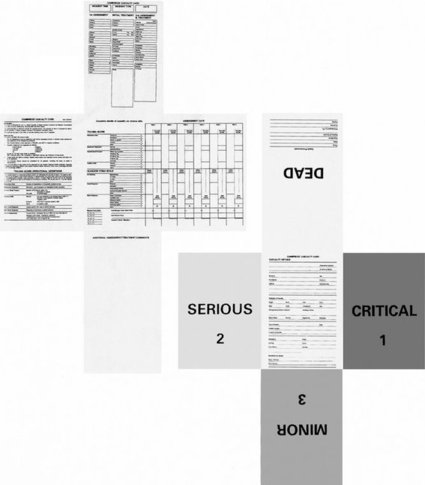

When patients arrive, they are assessed by medical staff and placed in one of three categories (Fig. 8.7):

1. Those requiring immediate and energetic treatment.

2. Those with minor injuries, or none at all.

3. Those with serious but non-urgent injuries who do not fit into either of the other categories.

|

| Fig. 8.7

Cambridge casualty card. One side carries a clinical record. The card can be folded so that the other side displays the state of the patient in a distinctive colour. The card is then placed in a plastic envelope and attached to the patient.

By kind permission of Carl Wallin Consultancy Services.

|

This classification of patients is known as ‘triage’ and was devised by French military surgeons during the Napoleonic Wars. Although ancient, it is still the best way of handling large numbers of casualties. It is best done by senior surgeons.

Organization at the scene of the incident

Incident Control Officers. Events at the scene of the incident are under the direction of the Incident Control Officer (ICO), usually the senior police officer present, or the senior fire officer if the incident is a fire. Each service – Fire, Police and Ambulance – also has its own ICO at the scene.

Incident Medical Officer. The ICO will request the presence of an Incident Medical Officer (IMO) whenever there are casualties. An accident and emergency consultant from another hospital or a general practitioner from the accident rescue service, if one is available, are common choices for such tasks because they are not needed at the designated hospital. The IMO takes charge of assessing patients, preparing them for transfer to hospital and any treatment that may be required at the scene. The IMO is not responsible for the organization of rescue services, which remains with the ICO.

In some circumstances, the IMO will ask for a mobile surgical team to be sent to the scene of the incident. The mobile surgical team includes nurses and other staff, who take with them equipment kept ready in the accident department for such a request.

First- and second-line hospitals

It is unusual for there to be so many accident victims that the designated hospital cannot cope, but major incident routines include provision for this with a ‘second-line’ or back-up hospital, nominated if more than a certain number of patients (usually 30) is anticipated. No patients are sent to the second-line hospital until the full quota has gone to the designated hospital. Thereafter, all patients go to the second-line hospital and, if necessary, a third-line hospital when that is full.

Patients sent to the second-line hospital are usually more seriously injured than those sent to the designated hospital, because this receives patients most easily accessible and most easily moved.

Military surgery

Although only a few surgeons are involved in the treatment of battle injuries, the principles are important for all wound management because much of the surgery of warfare concerns the management of contaminated soft tissue injuries in fit young men, without the resources of a modern hospital.

On the conventional battlefield, wounds are usually contaminated with earth, and delay allows time for infection, particularly anaerobic infection, to become established. All such wounds are potentially lethal, which is why the old military surgeons treated open fractures by immediate amputation (see ‘Simple and compound’ fractures, p. 97).

In urban warfare, the position is different. Patients can be seen by specialist surgeons in ideal circumstances less than an hour from injury. However quickly the patient receives treatment, the mainstay in the management of gunshot wounds is still wide excision and delayed primary suture (p. 141).