Chapter 35 Imaging in Thyroid Cancer

Introduction

Although thyroid cancer represents less than 1% of all malignancies worldwide, it is currently one of the most rapidly increasing malignancies in the Western world.1 Thyroid nodules can be palpated in 4% to 7% of patients and can be detected on imaging in approximately 50% of the general population.1–3 Five percent of these nodules represent cancer.1,2 With newly available imaging modalities, more and more asymptomatic and nonpalpable nodules are detected, making it imperative that primary care doctors and radiologists understand how to interpret these diagnostic studies, understand indications for further referral, and manage the long-term survivors of thyroid cancer. Most of the patients who have thyroid cancer have well-differentiated cancers, with an excellent long-term prognosis. Some patients have well-differentiated cancers with a poor prognosis, and some have other less common types of thyroid cancers. The challenge for the clinician is to identify the patients who have cancers, to treat them according to the extent and aggressiveness of their disease, and to limit morbidity and mortality.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Over the last few decades, the incidence of thyroid cancer has increased dramatically. It is unclear whether this increased incidence is real or whether it may be attributable to increased detection by newer diagnostic imaging techniques.4,5 Autopsy studies have shown that up to 30% of adults have incidental cancers smaller than 1 cm at the time of death.6 The average age of diagnosis of thyroid cancer is 47 years, and the average age of death is 74 years.5 The most common type is the papillary thyroid cancer (PTC); it accounts for approximately 70% of all thyroid cancers. Follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) represents approximately 15% of cancers and, in combination with PTC, composes the category of well-differentiated thyroid carcinomas. Grouped into the less common cancers are medullary (4-6%), anaplastic (3-4%), and others (≤5%). This group may include lymphoma, sarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and metastases.5

The most significant environmental risk factor for developing thyroid cancer is prior exposure to ionizing radiation, which can be due to either medical treatment or nuclear fallout (e.g., atomic bomb/testing survivors, nuclear energy accidents). The effects of ionizing radiation are most pronounced in children, especially those younger than 10 years old at the time of exposure. The latency period of developing cancer from this exposure is approximately 10 years for patients having external beam radiation exposure to less than 5 years for victims of the Chernobyl nuclear accident in the Ukraine.7 The increased risk persists for 30 to 40 years.8,9 Patients presenting with benign thyroid disease may also be at higher risk of harboring a malignant nodule; for example, cold nodule found on radionuclide scanning in patients with Graves’ disease may be malignant 15% to 38% of the time and complex cysts in thyroid disease may harbor a malignancy approximately 17% of the time.7 Given that, overall, two thirds of thyroid cancer cases occur in women, there would seem to be a link between reproductive hormones and the development of thyroid cancer. Estrogen has been linked as a stimulus for genomic instability, which may explain how it exerts its mutagenic effects on the thyroid.10 There are no definite data on the role of dietary iodine and its role in the development of thyroid cancer.11 Certain genetic syndromes increase the risk for thyroid cancer, or are associated with thyroid cancer, especially medullary thyroid cancer, which has been linked to several specific genetic abnormalities. In some cases, PTC follows a familial pattern. Several rare genetic disorders, including Cowden’s disease, multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN), and Gardner’s syndrome, are also associated with a higher incidence of thyroid cancer.5

Anatomy

The thyroid is a shield-shaped gland that consists of right and left lobes connected by the isthmus in midline, although occasionally, the isthmus can be absent. The thyroid isthmus is anterior to the trachea, usually overlying the first through the third tracheal rings. The thyroid gland typically terminates above the level of the clavicle; however, substernal extension into the superior mediastinum can occur. An accessory lobe, the pyramidal lobe, may be present in 50% to 70% of people and usually arises from the isthmus and extends superiorly.12 The visceral fascia, part of the middle layer of the deep cervical fascia, attaches the thyroid gland to the larynx and trachea. As a result, the gland or abnormalities related to it will move with the larynx during swallowing. The arterial supply to the gland is derived from two separate paired vessels. The inferior thyroid vessels come directly off of the thyrocervical trunk and supply the inferior part of the gland as well as both the superior and the inferior parathyroids. The superior thyroid artery arises as the first branch of the external carotid artery and supplies the superior portion of the gland. Rarely, a small artery or pair of arteries may come directly from the aorta or brachiocephalic trunk, named the thyroid ima artery. There are three main paired veins that drain the thyroid. There is some variability in location and presence, but they generally drain into the internal jugular veins and innominate vein. The lymphatics of the thyroid consist of intraglandular and extraglandular components. Extraglandular lymphatics generally follow venous flow; the inferior portions of the lateral lobes drain along the tracheoesophageal groove into the central neck. The superior parts of the lobes drain toward the superior thyroid veins, and the isthmus may drain toward the delphian (prelaryngeal) lymph node or central neck nodes. More unusual, but clearly documented, are lymphatic pathways to the retropharyngeal region, accounting for metastases to the skull base. Based on clinical and anatomic review, the central lymphatics are generally considered the primary drainage pathways for thyroid cancers, with the lateral neck nodes being considered secondary levels of lymphatic spread. These facts are important from an imaging and a treatment perspective.13 The parathyroid glands are also closely related to the thyroid anatomically. They tend to lie on the undersurface of the thyroid and receive their blood supply from the inferior thyroid artery.

Pathology

Tumor Types

Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

The most common type is the PTC, which accounts for approximately 70% of all thyroid cancers. This cancer has a favorable prognosis with most of the patients who are treated; either cured of their disease or live for many years after the initial diagnosis. Less than 50% of recurrences occur within the first 5 years, and sometimes recurrences can present several years after the initial diagnosis.12 The cancer often retains the ability to concentrate iodine, secrete thyroglobulin, and respond to thyrotropin-stimulating hormone (TSH) stimulation. There are several variants of PTC. The follicular variant of PTC has a pattern of neoplastic follicles that are small with little colloid. They contain relatively fewer nuclear inclusions and psammoma bodies. The prognosis and biologic behavior are similar to that of PTC. The tall cell variant has neoplastic cells in which the height is twice the width. It is associated with more aggressive biologic characteristics and tends to metastasize earlier in its course. It is common for PTC to demonstrate multifocal disease within the thyroid gland at the time of histologic examination. The incidence has been reported to be as high as 80% in the literature.5 Extrathyroidal extension of the tumor is seen and has prognostic significance.14 The overlying strap muscles in the neck are the most commonly invaded structures. Cases of tracheal, laryngeal, esophageal, and other soft tissue extensions in the neck are sometimes seen.

Follicular Thyroid Carcinoma

FTC is the second most common type of thyroid cancer. It represents approximately 15% of thyroid cancers. Many authors have suggested that the prognosis is slightly poorer than that for PTC. Both benign and malignant follicular lesions demonstrate follicular cells arranged in microfollicles, rosettes, or spindles, and thus, they cannot be differentiated on fine-needle aspiration. Capsular invasion is the only current method of distinguishing between the two entities, and hence, quite often, the diagnosis is made after surgery, unless extracapsular extension is seen on imaging before surgery. In patients who have minimal capsular invasion, the prognosis is excellent, and few patients develop distant metastases or die of disease.5,15 Unfortunately, patients with capsular invasion have worse prognosis. Young patients and women may have a slightly better prognosis than men. Clinically, FTCs tend to present with a solitary thyroid mass. The incidence of multicentric disease within the thyroid is much lower than with PTC.

Hurthle Cell Carcinoma

Hurthle cell carcinoma is a variant of FTC, accounting for 3% to 5% of all thyroid cancers.16 It is composed of large acidophilic or oncocytic cells that do not take up radioiodine as well as classic FTC. Like FTC, the diagnosis can be made only after examination of the entire tumor capsule. The cancers generally have a slightly worse prognosis than other FTCs. They are associated with a higher rate of lymph node and distant metastasis than other FTCs.17

Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) arises from the parafollicular or C cells, which are a part of the amine precursor uptake and decarboxylation (APUD) cell system. These cells produce calcitonin and are unrelated to the iodine-concentrating and thyroid hormone production of the gland. MTC is more closely related to other tumors of the neuroendocrine system such as the carcinoid tumors and pheochromocytomas. MTC is rare, accounting for 3% to 5% of thyroid cancers.5 The familial form, which is less common than the sporadic form of MTC, is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. It can be inherited as a part of three distinct entities. The most common, MEN IIA, is associated with pheochromocytoma and hyperparathyroidism. The second most common, MEN IIB, is associated with pheochromocytoma, mucosal neuromas, and marfanoid body habitus. The least common, familial medullary thyroid cancer (FMTC), consists of MTC only. The presence of MTC has been strongly linked to the RET oncogene, located on chromosome 10. The discovery of this gene mutation has been studied extensively and has had a significant effect on diagnosis, management, and understanding of these tumors.5 Clinically, patients tend to present with a solitary thyroid nodule. Some patients present with an enlarging neck mass or, rarely, with signs of local invasion, including hoarseness or dysphagia. Some patients can present with paraneoplastic syndromes, such as Cushing’s or carcinoid syndrome.

Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma

Anaplastic thyroid cancer is an aggressive disease, usually proving fatal within several weeks to months of diagnosis. It represents approximately 3% to 5% of thyroid cancers.5 This cancer tends to affect elderly patients, and the peak incidence is in the seventh decade.18 Some investigators believe that anaplastic carcinoma may represent a dedifferentiation of well-differentiated cancers.19 Clinically, patients present with a rapidly growing neck mass, often in the context of a slow-growing mass or goiter for several decades. Patients often present with signs of local invasion such as dysphagia, dyspnea, hoarseness, sore throat, and neck pain.

Lymphoma of the Thyroid Gland

Lymphoma of the thyroid has been reported to make up 2% to 5% of thyroid cancers.20 It tends to be non-Hodgkin’s B-cell type, although other types do occur. Patients with Hashimoto’s disease (chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis) have a 70-fold increased incidence of thyroid lymphoma compared with the general population.20 It is suspected that chronic autoimmune stimulation is responsible for the development of this cancer.20 Many lymphomas can be diagnosed cytologically, based on their monoclonality. Differentiating them from anaplastic carcinoma is often challenging, however, and it is not uncommon to require core or open biopsy to make an accurate diagnosis. In the clinical setting, lymphoma also mirrors anaplastic carcinoma in many ways. It tends to present with a rapidly expanding mass in the neck, often fixed to surrounding structures. Patients often have neck pain, hoarseness, dysphagia, and even facial edema. The tumor is often fixed to surrounding structures, including the trachea and larynx, the esophagus, and the skin.

Other Cancers of the Thyroid

Although rare, several other cancers can involve the thyroid, either primarily or through metastasis. Squamous cell carcinoma is a rare primary cancer of the thyroid. Once diagnosed, a thorough workup must be performed to rule out a head and neck primary that has merely metastasized to the thyroid. Metastatic cancer to the thyroid is also rare, although well documented. It is suspected that the significant vascularity of the gland accounts for these metastases. Cancers of the kidney, lung, breast, and melanoma are the most commonly documented.5 In patients who have a known history of other primary cancers who have a new thyroid mass, the possibility of metastatic disease must be entertained.

Gross and Microscopic Features

On gross pathology, PTC is poorly encapsulated, firm, and often has calcifications (psammoma bodies) within their substance. The presence of these calcifications is of diagnostic significance, because they are rarely present in other cancers. Larger tumors may contain focal areas of hemorrhage and necrosis. PTC demonstrates papillary fronds along with follicular components. The nuclei have a characteristic appearance, with a feature described as “Orphan Annie eyes” used to refer to the relatively empty appearance of the nucleoplasm.5

FTC has a thick capsule with focal necrosis and cystic changes.21 The cells are small and monotonous and organized into follicles with sparse amount of colloid. Psammoma bodies are rare compared with PTC.

MTCs are well-encapsulated tumors. Histologically, the tumor demonstrates amyloid depositions in 60% to 80% of cases.22 The tumor often displays nuclear pleomorphism, necrosis, and multiple mitosis. Calcitonin staining is also helpful, and the level of staining may reflect the level of cellular differentiation. Serum calcitonin levels are useful as a diagnostic and measure of response to therapy. MTC have been reported to secrete multiple polypeptide hormones, adrenocorticotropic hormone, somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal peptide, chromogranin A, neuron-specific enolase, and substance P.5 Carcinoembryonic antigen is also secreted by many MTCs and has been used as a tumor marker and a receptor for nuclear imaging with octreotide imaging.

Clinical Presentation

Most of the patients with thyroid cancer commonly self-diagnose a lump in their neck found during palpation. Other patients may present with a thyroid nodule detected incidentally on imaging ordered for other medical reasons. Other symptoms that may be seen in thyroid cancer include dysphagia, change in voice, coughing, choking, dyspnea, and pain. There may be a history of exposure to ionizing radiation and a family history of thyroid or parathyroid disease. Physical examination should assess for features of the nodule and for the presence of cervical lymphadenopathy. Suspicious features for cancer include nodules that are hard, fixed, irregular, 4 cm or larger, or with associated lymphadenopathy. A general rule to follow is that any lesion with two or more associated high-risk characteristics may have a malignancy rate greater than 80%.23

Patterns of Tumor Spread

Regional metastasis to the neck and mediastinal lymph nodes is the common pattern of spread for PTC, with incidence rates from 40% to more than 75%.24 The role of regional metastasis on overall prognosis of PTC is still being debated.12,25 Unlike regional metastasis, distant metastasis does seem to adversely affect prognosis. Approximately 10% of patients demonstrate metastasis to distant sites, most commonly to the lungs, brain, and bones.26

Patients with anaplastic tumors may demonstrate cervical metastasis. Distant metastasis tends to be to the lungs, although other sites, including bone, brain, and mediastinum, have been demonstrated.27

Staging Evaluation

Table 35-1presents the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) system diagnosis.28

| Primary Tumor (T) |

| TXPrimary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0No evidence of primary tumor |

| T1Tumor ≤ 2 cm in greatest dimension limited to the thyroid |

| T2Tumor ≥ 2 cm but not > 4 cm in greatest dimension limited to the thyroid |

| T3Tumor > 4 cm in greatest dimension limited to the thyroid or any tumor with minimal extrathyroid extension (e.g., extension to sternothyroid muscle or perithyroid soft tissue) |

| T4a Tumor of any size extending beyond the thyroid capsule to invade subcutaneous soft tissues, larynx, trachea, esophagus, or recurrent laryngeal nerve |

| T4b Tumor invades prevertebral fascia or encases carotid artery or mediastinal vessels |

| All anaplastic carcinomas are considered T4 tumors: |

| T4a: Intrathyroid anaplastic carcinoma–surgically resectable |

| T4b: Extrathyroid anaplastic carcinoma–surgically unresectable |

| Note: All categories may be subdivided: (a) solitary tumor or (b) multifocal tumor (the largest determines the classification). |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) |

| Regional lymph nodes are the central compartment and lateral cervical and upper mediastinal lymph nodes |

| NXRegional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1Regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1aMetastasis to level VI (pretracheal, paratracheal, and prelaryngeal/delphian lymph nodes) |

| N1bMetastasis to unilateral, bilateral, or contralateral cervical or superior mediastinal lymph nodes |

| Distant Metastasis (M) |

| MXDistant metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0No distant metastasis |

| M1Distant metastasis |

| Stage Grouping |

| Separate stage groupings are recommended for papillary, follicular, medullary, and anaplastic (undifferentiated) carcinoma |

| Papillary or Follicular |

| Younger than 45 years |

| Stage I: Any T, Any N, M0 |

| Stage II: Any T, Any N, M1 |

| 45 years and older |

| Stage I: T1, N0, M0 |

| Stage II: T2, N0, M0 |

| Stage III: T3, N0, M0 |

| T1, N1a, M0 |

| T2, N1a, M0 |

| T3, N1a, M0 |

| Stage IVA: T4a, N0, M0 |

| T4a, N1a, M0 |

| T1, N1b, M0 |

| T2, N1b, M0 |

| T3, N1b, M0 |

| T4a, N1b, M0 |

| Stage IVB: T4b, Any N, M0 |

| Stage IVC: Any T, Any N, M1 |

From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York: Springer; 2010.

Imaging

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice to evaluate all palpable and nonpalpable thyroid nodules. It is extremely sensitive for detection of thyroid nodules missed on physical examination or other imaging modality. In addition, ultrasound screening is recommended for all patients at high risk of thyroid malignancy (FMTC, MEN IIb, or significant radiation exposure) and for patients with multinodular goiter.3 Ultrasound may be the only imaging modality in assessing uncomplicated thyroid nodules with no associated palpable neck adenopathy.

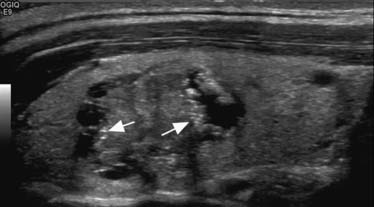

Along with size determination, ultrasound helps to characterize thyroid nodules and to stratify a nodule’s risk of cancer. The characteristics of thyroid nodule evaluated for identifying cancers include echogenicity of the nodule, the nodule’s boundary, the presence of a sonolucent halo, calcifications, and internal structure. The nodule’s echogenicity should be described by using normal thyroid tissue as a reference; with the nodule described as “hypoechoic,” “isoechoic,” or “hyperechoic.” Hypoechoic solid nodules transmit the ultrasound wave with minimal reflection, whereas hyperechoic nodules reflect a greater proportion of the signal. Isoechoic nodules are similar to the normal thyroid tissue. A thyroid cyst is characterized as thin-walled without internal structure, with an increased echo pattern behind the structure. Cysts are rare and benign, but cystic degeneration of solid nodules, benign or malignant, is common. Intralesional calcifications are seen as bright echogenic densities that greatly attenuate the ultrasound beam, a phenomenon known as shadowing.

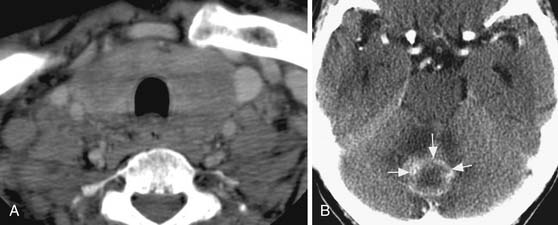

Sonographic features that increase the possibility of malignancy includes hypoechogenicity, microcalcification (Figure 35-1), irregular margins, and chaotic vascular pattern, as well as extracapsular invasion and lymph node involvement.29 However, these features are suggestive of malignancy because there are no definite sonographic features that are specific for thyroid cancer. Many thyroid cancers are less echogenic than surrounding normal thyroid tissue; hyperechoic lesions are unlikely to be of clinical significance.30 However, benign nodules can also be hypoechoic on imaging. Punctate calcifications are rare but suggest the presence of psammoma bodies in PTCs.31 Peripheral or eggshell-like calcification generally indicates a benign nodule. However, chronic cancers may uncommonly demonstrate peripheral calcification. Coarse, scattered calcifications may be seen in benign or malignant nodules, especially hemorrhagic lesions. Large areas of calcification may be seen in MTCs. An ill-defined margin of a nodule may be a marker of aggressiveness of the thyroid nodule, with cancers that have invaded surrounding tissue having a poorly defined, irregular border.32 However, the sharpness of the nodule’s border probably has little diagnostic value. An incomplete halo has been reported as a feature of malignancy but has neither high sensitivity nor specificity.

The presence of at least two suspicious songographic criteria reliably identifies most neoplastic lesions of the thyroid gland. Identifying vascular invasion may be the most reliable predictor of malignancy but is uncommonly seen. However, definitive differentiation between benign and malignant lesions with current ultrasound technology is not possible. The positive or negative predictive value of sonographic characteristics vary widely, with the predictive value 97% for cytologically diagnosed cancer and 96% for benign disease.33 In addition, sonography is important to detect or confirm cervical lymphadenopathy in patients with a high risk of thyroid cancer and is essential to detect recurrence after thyroidectomy.

Finally, ultrasound guidance of the biopsy can be used to decrease the rate of nondiagnostic fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Ultrasound-guided aspiration biopsy is valuable in patients with palpable thyroid nodule, multinodular goiter, all patients with high risk of malignancy, and for cervical lymphadenopathy.3 Similarly, biopsy seems appropriate in nonpalpable thyroid nodules in patients with a high risk of cancer or in those with nodules larger than 1 to 1.5 cm and ultrasound features concerning for malignancy.34 Small nonpalpable lesions with benign sonographic features should be reevaluated with sonography at perhaps yearly intervals.

Isotope Scanning

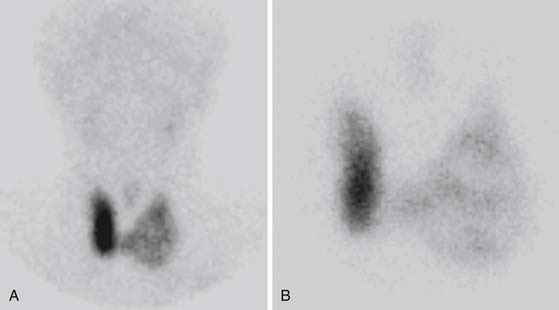

Thyroid scintigraphy, using 99mTc pertechnetate, 123I, or 131I, is used for assessment of thyroid function, detection of autonomously functioning thyroid nodules, and evaluation of thyroid cancer extent. Thyroid follicular cells can take up iodine and 99mTc pertechnetate; however, only iodine is organified and stored (as thyroglobulin) in the lumen of thyroid follicles. 99mTc and 123I scintigraphy is primarily recommended for functional assessment in cases in which TSH concentration is suppressed in patients with suspected hyperthyroidism (e.g., Graves’ disease, autonomously functioning nodule, or toxic multinodular goiter) or in which ectopic thyroid tissue is suspected.3

Conversely, 99mTc and 123I scintigraphy is utilized to functionally classify thyroid nodules. Based on the pattern of isotope uptake, nodules are classified as cold (decreased uptake) (Figure 35-2), hot (increased uptake), or warm (uptake similar to surrounding tissue). Thyroid scintigraphy is also recommended in a subset of patients who have indeterminate fine-needle aspiration results. Hot nodules on scintigraphy are rarely malignant.35 A review of published reports of radionuclide scanning reveals that 84% of solitary thyroid nodules are cold, 10% are warm, and the remaining 5% are hot. A cold thyroid nodule is more likely to be malignant, but most thyroid nodules are cold (~84%), including many benign lesions.1,36 The sensitivity of scintigraphy for detection of cold nodule is further limited in smaller lesions (<1 cm) owing to the limited spatial resolution of the camera. Approximately 5% of thyroid nodules will concentrate pertechnetate with no uptake on the 123I scan.37 These discordant nodules will appear as hot or warm nodules on 99mTc pertechnetate scan but as cold nodules on radioiodine scan. Although the majority of these nodules are benign, few represent thyroid cancers. As a result, patients with nodules that are functioning on pertechnetate imaging should undergo radioiodine imaging. 131I can be used diagnostically in order to measure the uptake within the hyperfunctional gland or for localization of recurrent or metastatic thyroid cancer in patients with thyroid cancer that concentrates iodine. Conversely, 131I can be delivered at a therapeutic dose for radioiodine treatment of a hyperfunctional gland or nodule. Similarly, it is considered the treatment of choice for residual, recurrent, or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer.

Fluorine-18–labeled Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose Positron-Emission Tomography Scanning

The clinical role of fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan in preoperative evaluation of thyroid nodules is controversial and is not routinely used in daily clinical practice. Focal FDG uptake is incidentally seen in approximately 2% of all patients, and one third of these lesions are thyroid cancer.38 However, benign lesions also demonstrate FDG uptake. FDG-PET scan has an increasing role in the evaluation of selected patients treated for thyroid cancer with clinically negative examinations and rising thyroglobulin level. The uptake of FDG in general is inversely proportional to iodine uptake/differentiation. Therefore, it may be particularly useful in metastatic thyroid tumors that do not concentrate radioiodine.39 Potential pitfalls include indolent or well-differentiated thyroid tumors that take-up FDG poorly and FDG uptake that may not be related to metastatic thyroid cancer. Additional limitation of PET is that cancerous nodes may not be detected on PET owing to low cellularity or because they are predominantly cystic or necrotic.

Other Diagnostic Imaging (Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

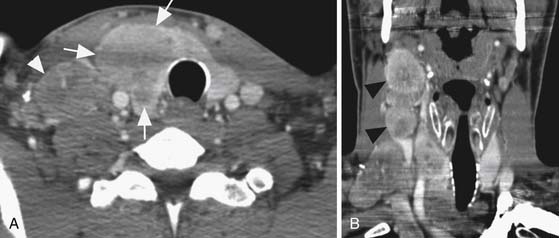

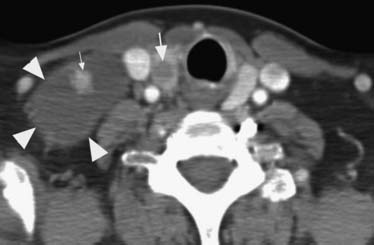

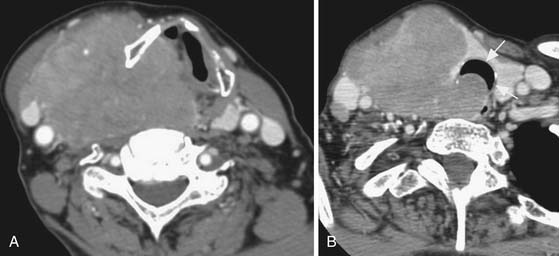

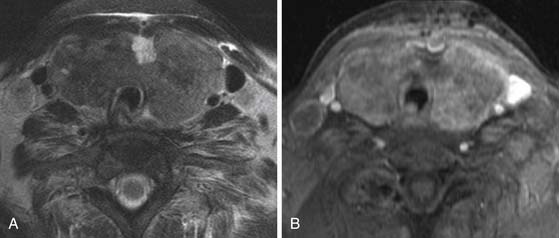

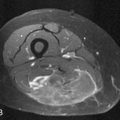

Cross-sectional imaging, using CT scan (Figures 35-3 to 35-6) and MRI (Figure 35-7), is not indicated to primarily evaluate the intrathyroid nodules as benign, and malignant nodules may have a similar imaging appearance. Its main role is to assess for local aggressiveness including extracapsular extension, lymph node metastasis (see Figures 35-3 and 35-4), infiltration of the strap muscles, invasion to the airway (see Figure 35-6) and esophagus, and invasion of the prevertebral musculature. Consequently, cross-sectional imaging is usually obtained when patients present with features concerning for aggressive cancer including a fixed, immobile thyroid mass or are symptomatic with hoarseness, dysphagia, or respiratory symptoms. In addition, cross-sectional imaging is frequently requested for evaluation of the extent of the disease in the neck and mediastinum for surgical planning and to look for distant metastasis (see Figure 35-5). Diagnostic CT often requires iodinated contrast, which may be contraindicated if iodine-131 whole body scanning or ablation therapy is a consideration. MRI can be helpful because it is highly sensitive for evaluation of local disease in the neck without the concern about iodinated contrast agents.

Treatment

Surgery

There are two potential surgical approaches to differentiated thyroid cancer: total (or near-total) thyroidectomy and unilateral lobectomy and isthmusectomy. Total thyroidectomy involves removal of all thyroid tissue. This more aggressive surgical approach is associated with lower rates of local and regional recurrence and a lower mortality in high-risk patients. One half of patients who die from recurrent thyroid cancer die from complications of central neck recurrence.40 Near-total thyroidectomy is identical except for preserving the posterior thyroid capsule of the lobe contralateral to the thyroid tumor. During a unilateral lobectomy and isthmusectomy, one entire lobe and the isthmus are removed, without entering the contralateral neck. Subtotal thyroidectomy is an inadequate procedure for patients with thyroid cancer. It is associated with a higher complication rate if subsequent surgery is required.

Total thyroidectomy is recommended if the primary tumor is 1.0 cm in diameter or greater or there are the presence of extrathyroidal extension of tumor or metastases. This operation should also be performed in all patients with thyroid cancer who have a history of exposure to ionizing radiation of the head and neck owing to the higher rate of tumor recurrence. Foci of papillary cancer are found in both thyroid lobes in up to 36% to 85% of patients,41,42 with 5% to 10% of thyroid cancer recurrences in the contralateral lobe.43 In addition, radioiodine ablation of thyroid bed remnants and treatment of metastatic disease is facilitated by resection of as much thyroid tissue as possible. The specificity of measurements of serum thyroglobulin as a tumor marker is facilitated by removal of nearly all normal thyroid tissue. Unilateral lobectomy and isthmusectomy is considered if the tumor is less than 1.0 cm in diameter (or even ≤ 3 cm if entirely confined to the thyroid in low-risk patients) and confined to one lobe of the gland. For patients with a cytologically suspicious nodule, and not proven cancer, a unilateral lobectomy and isthmusectomy is usually performed.

Lymph node dissection should be performed if there is clinical evidence of cervical or mediastinal nodal metastases.44 Pathologic adenopathy of the central neck will require resection of all nodal groups in this area. The presence of pathologic adenopathy lateral to the jugular vein indicates a need for a modified radical neck dissection. The precise role of prophylactic neck dissection of microscopic lymph node metastases that are not clinically identifiable is controversial because it may not improve long-term outcome.45 In addition subsequent radioiodine administration will ablate these occult foci. However, in experienced hands, this procedure can be done with minimal additional risk and some studies have suggested a survival benefit in selected patients.46

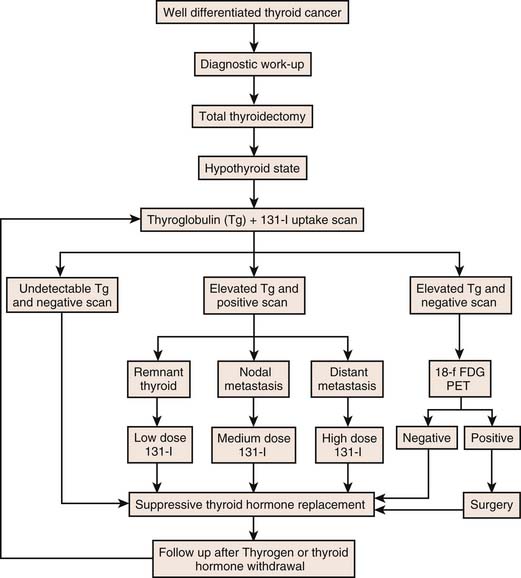

Radioiodine Ablation Therapy and Chemotherapy

The advantage of radioiodine therapy in the postthyroidectomy treatment of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer includes adjuvant ablation of residual thyroid tissue and possible microscopic residual cancer, imaging for possible metastatic disease, and treatment of known residual or metastatic thyroid cancer. In addition, the sensitivity of serum thyroglobulin measurements is improved during follow-up for recurrence. 131I treatment after thyroidectomy has decreased the 30-year recurrence and disease-specific mortality rates by approximately 50%.44 Radioiodine therapy is indicated for all patients with known distant metastases, gross extrathyroidal extension of the tumor regardless of tumor size, or primary tumor size larger than 4 cm even in the absence of other high-risk features.47 Radioiodine ablation is not routinely recommended for patients with unifocal cancer smaller than 1 cm without other high-risk features. Chemotherapy may occasionally be beneficial in patients with progressive symptomatic thyroid cancer that is unresponsive or not amenable to surgery, radioiodine therapy, or external radiotherapy. Nevertheless, no chemotherapeutic regimen has been consistently successful, whether using single-agent or multiagent chemotherapy.48 Treatment guideline is generally dictated by the results of case reports or small retrospective series.

Radiation

External irradiation is rarely used as adjunctive therapy in the initial management of patients with well-differentiated thyroid cancer.49 Radiation therapy may be beneficial, however, in patients with poorly differentiated thyroid cancer whose tumors do not concentrate radioiodine. External beam radiotherapy also has been used as adjuvant therapy after complete surgical excision to prevent recurrence, after incomplete surgical resection or local recurrence to provide regional tumor control, and as palliative therapy for distant metastases. Radiotherapy has been used in patients with all types of thyroid epithelial cancer, MTC, and thyroid lymphoma. It can be given as primary therapy to treat unresectable cancer, as adjuvant therapy after surgical resection, and as palliative therapy for recurrent cancer. It can be given alone or in combination with surgery or chemotherapy.

Surveillance

Most recurrences of differentiated thyroid cancer occur within the first 5 years after initial treatment, although recurrences may occur many years later, particularly with papillary cancer.50 All patients should have periodic physical examination, biochemical testing, and anatomic or functional imaging to monitor for recurrence. Anatomic imaging using ultrasound, CT, or MRI, or functional imaging, using 131I or PET scan, is essential for evaluation of tumor recurrence. There has been a shift in using biochemical testing for monitoring recurrence, in comparison with imaging, which is used if there is clinical and biochemial evidence of recurrence.

Serum Thyroglobulin Measurement

Following thyroidectomy and ablation of any thyroid remnant, the serum thyroglobulin concentration should be very low (<1-2 ng/mL), both during T4 therapy and after it is discontinued or stimulated by rhTSH. A stimulated thyroglobulin value of at least 2 ng/mL or higher suggests recurrence and, consequently, more extensive evaluation is indicated. Patients with lower values of thyroglobulin may still present with localized recurrence during subsequent years of follow-up. The positive predictive value of the initial thyroglobulin greater than 2 ng/mL is 80% and the negative predictive value is 98%.51 Antithyroglobulin antibodies, present initially in approximately 25% of patients with thyroid cancer, may interfere with all assays for thyroglobulin. As a result, the laboratory should always test for antithyroglobulin antibodies before measuring serum thyroglobulin.

In low-risk patients with a thyroglobulin level of less than 2 ng/mL, a combination of neck ultrasound and rhTSH-stimulated thyroglobulin is effective at detecting persistent/recurrent disease. A combination of rhTSH-stimulated thyroglobulin and neck ultrasound has a better predictive value than rhTSH-stimulated thyroglobulin either alone or in combination with radioiodine scanning.52 Diagnostic whole body radioiodine scanning is unnecessary if rhTSH-stimulated serum thyroglobulin concentration is less than 2 ng/mL53; however, whole body scanning is necessary in the follow-up of higher-risk patients. A 2003 consensus statement suggests relying upon rhTSH-stimulated thyroglobulin testing instead of radioiodine scanning in all low-risk patients.54

Imaging

Ultrasonography has been particularly useful in identifying recurrent cancer in the thyroid bed after thyroidectomy or lobectomy, in the contralateral lobe and in the lymph nodes. Following thyroidectomy, cervical ultrasound should be performed to evaluate the thyroid bed and central and lateral cervical nodal compartments at 6 and 12 months, and then annually for at least 3 to 5 years, depending on the patient’s risk for recurrent disease and thyroglobulin status. Sonographic lymph node characteristics most consistent with malignancy are a cystic appearance, microcalcification, loss of hilum, and peripheral vascularization.55 In addition, ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration is highly effective in evaluating and detecting regional recurrence in previously treated patients. Cross-sectional imaging, using CT scan and MRI, is essential for evaluation of the extent of recurrent disease including adenopathy in the neck and mediastinum.

The use of rhTSH before FDG-PET scan significantly increases the number of lesions detected.56 FDG-PET may complement 131I scanning57 because FDG uptake, in general, is inversely proportional to iodine uptake/differentiation. Therefore, it may be particularly useful in metastatic thyroid tumors that do not concentrate radioiodine.

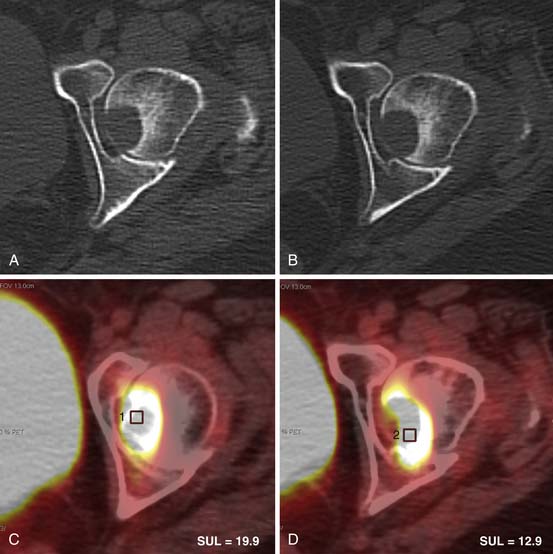

In patients with evidence of distant metastases, FDG-PET scanning may provide useful prognostic information.58 This was illustrated in a study of 125 patients with well-differentiated thyroid cancer who underwent FDG-PET scanning, uptake of FDG in a large volume of tissue correlated with poor survival, predicting outcome better than uptake of radioiodine (Figure 35-8).

1. Ghassi D., Donato A. Evaluation of thyroid nodule. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:190-195.

2. Pacini F., Schlumberger M., Dralle H., et al. European consensus for the management of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma of the follicular epithelium. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:787-803.

3. Singer P.A., Cooper D.S., Daniels G.H., et al. Treatment guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and well-differentiated thyroid cancer. American Thyroid Association. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2165-2172.

4. Hall S.F., Walker H., Siemens R., Schneeberg A. Increasing detection and increasing incidence in thyroid cancer. World J Surg. 2009;33:2567-2571.

5. Newman J.G., Chalian A.A., Shaha A.R. Surgical approaches in thyroid cancer: what the radiologist needs to know. Neuroimag Clin North Am.. 2008;18:491-504.

6. Bramley M.D., Harrison B.J. Papillary microcarcinoma of the thyroid gland. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1674-1683.

7. Suliburk J., Delbridge L. Surgical management of well differentiated thyroid cancer: state of the art. Surg Clin North Am.. 2009;89:1171-1191.

8. Schneider A.B., Sarne D.H. Long-term risks for thyroid cancer and other neoplasms after exposure to radiation. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2005;1:82-91.

9. Acharya S., Sarafoglou K., LaQuaglia M., et al. Thyroid neoplasms after therapeutic radiation for malignancies during childhood or adolescence. Cancer. 2003;97:2397-2403.

10. Li J.J., Weroha S.J., Lingle W.L., et al. Estrogen mediates Aurora-A overexpression, centrosome amplification, chromosomal instability, and breast cancer in female ACI rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:18123-18128.

11. Harach H.R., Escalante D.A., Day E.S. Thyroid cancer and thyroiditis in Salta, Argentina: a 40-yr study in relation to iodine prophylaxis. Endocr Pathol. 2002;13:175-181.

12. Cady B., Sedgwick C.E., Meissner W.A., et al. Changing clinical, pathologic, therapeutic, and survival patterns in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Ann Surg. 1976;184:541-553.

13. Loevner L.A., Kaplan S.L., Cunnane M.E., Moonis G. Cross-sectional imaging of the thyroid gland. Neuroimag Clin North Am.. 2008;18:445-461.

14. Shaha A.R. TNM classification of thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg. 2007;31:879-887.

15. Emerick G.T., Duh Q.Y., Siperstein A.E., et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of follicular thyroid carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;72:3287-3295.

16. McDonald M.P., Sanders L.E., Silverman M.L., et al. Hurthle cell carcinoma of the thyroid gland: prognostic factors and results of surgical treatment. Surgery. 1996;120:1000-1004.

17. Carling T., Ocal I.T., Udelsman R. Special variants of differentiated thyroid cancer: does it alter the extent of surgery versus well-differentiated thyroid cancer? World J Surg. 2007;31:916-923.

18. Trimboli P., Ulisse S., Graziano F.M., et al. Trend in thyroid carcinoma size, age at diagnosis, and histology in a retrospective study of 500 cases diagnosed over 20 years. Thyroid. 2006;16:1151-1155.

19. Livolsi V., Merino M. Pathology of thyroid tumors. In: Thawley S., Panje W., Batsakis J., et al. Comprehensive Management of Head and Neck Tumors. Philadelphia: WB: Saunders; 1987:1710-1721.

20. Holm L.E., Blomgren H., Lowhagen T. Cancer risks in patients with chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:601-604.

21. Evans H.L. Follicular neoplasms of the thyroid. A study of 44 cases followed for a minimum of 10 years, with emphasis on differential diagnosis. Cancer. 1984;54:535-540.

22. Papaparaskeva K., Nagel H., Droese M. Cytologic diagnosis of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid gland. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;22:351-358.

23. Hegedus L. Clinical practice. The thyroid nodule. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1764-1771.

24. Lin J.D., Chen S.T., Hsueh C., et al. A 29-year retrospective review of papillary thyroid cancer in one institution. Thyroid. 2007;17:535-541.

25. Mazzaferri E.L. Papillary thyroid carcinoma: factors influencing prognosis and current therapy. Semin Oncol. 1987;14:315-332.

26. Hoie J., Stenwig A.E., Kullmann G., et al. Distant metastases in papillary thyroid cancer. A review of 91 patients. Cancer. 1988;61:1-6.

27. Shvero J., Gal R., Avidor I., et al. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. A clinical, histologic, and immunohistochemical study. Cancer. 1988;62:319-325.

28. Green F.L., Page D.L., Fleming I.D., et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer; 2002. 90-92

29. Cappelli C., Castellano M., Pirola I., et al. The predictive value of ultrasound findings in the management of thyroid nodules. QJM. 2007;100:29-35.

30. Solivetti F.M., Bacaro D., Cecconi P., et al. Small hyperechogenic nodules in thyroiditis: usefulness of cytological characterization. J Exp Clin Cancer Res.. 2004;23:433-435.

31. Kakkos S.K., Scopa C.D., Chalmoukis A.K., et al. Relative risk of cancer in sonographically detected thyroid nodules with calcifications. J Clin Ultrasound. 2000;28:347-352.

32. Ito Y., Kobayashi K., Tomoda C., et al. Ill-defined edge on ultrasonographic examination can be a marker of aggressive characteristic of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29:1007-1011.

33. Ito Y., Amino N., Yokozawa T., et al. Ultrasonographic evaluation of thyroid nodules in 900 patients: comparison among ultrasonographic, cytological, and histological findings. Thyroid. 2007;17:1269-1276.

34. Papini E., Guglielmi R., Bianchini A., et al. Risk of malignancy in nonpalpable thyroid nodules: predictive value of ultrasound and color-Doppler features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1941-1946.

35. Miller J.M. Thyroid carcinoma in an autonomously functioning nodule. J Nucl Med. 1980;21:296.

36. Giuffrida D., Gharib H. Controversies in the management of cold, hot, and occult thyroid nodules. Am J Med. 1995;99:642-650.

37. Reschini E., Ferrari C., Castellani M., et al. The trapping-only nodules of the thyroid gland: prevalence study. Thyroid. 2006;16:757-762.

38. Kang K.W., Kim S.K., Kang H.S., et al. Prevalence and risk of cancer of focal thyroid incidentaloma identified by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for metastasis evaluation and cancer screening in healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 88, 2003. 4100-4104

39. Nahas Z., Goldenberg D., Fakhry C., et al. The role of positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the management of recurrent papillary thyroid carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:237-243.

40. Silverberg S.G., Hutter R.V., Foote F.W.Jr. Fatal carcinoma of the thyroid: histology, metastases, and causes of death. Cancer. 1970;25:792.

41. Katoh R., Sasaki J., Kurihara H., et al. Multiple thyroid involvement (intraglandular metastasis) in papillary thyroid carcinoma. A clinicopathologic study of 105 consecutive patients. Cancer. 1992;15(70):1585-1590.

42. Pacini F., Elisei R., Capezzone M., et al. Contralateral papillary thyroid cancer is frequent at completion thyroidectomy with no difference in low- and high-risk patients. Thyroid. 2001;11:877-881.

43. Tollefsen H.R., Decosse J.J. Papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. recurrence in the thyroid gland after initial surgical treatment. Am J Surg. 1963;106:728.

44. Mazzaferri E.L., Jhiang S.M. Long-term impact of initial surgical and medical therapy on papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. Am J Med. 1994;97:418-428.

45. Scheumann G.F., Gimm O., Wegener G., et al. Prognostic significance and surgical management of locoregional lymph node metastases in papillary thyroid cancer. World J Surg. 1994;18:559-567. discussion 567–568

46. White M.L., Gauger P.G., Doherty G.M. Central lymph node dissection in differentiated thyroid cancer. World J Surg. 2007;31:895-904.

47. Cooper D.S., Doherty G.M., Haugen B.R., et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009;19:1167-1214.

48. Williams S.D., Birch R., Einhorn L.H. Phase II evaluation of doxorubicin plus cisplatin in advanced thyroid cancer: a Southeastern Cancer Study Group Trial. Cancer Treat Rep. 1986;70:405-407.

49. Brierley J.D., Tsang R.W. External radiation therapy in the treatment of thyroid malignancy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am.. 1996;25:141-157.

50. Shaha A.R., Loree T.R., Shah J.P. Prognostic factors and risk group analysis in follicular carcinoma of the thyroid. Surgery. 1995;118:1131-1136.

51. Kloos R.T., Mazzaferri E.L. A single recombinant human thyrotropin-stimulated serum thyroglobulin measurement predicts differentiated thyroid carcinoma metastases three to five years later. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5047-5057.

52. Pacini F., Molinaro E., Castagna M.G., et al. Recombinant human thyrotropin-stimulated serum thyroglobulin combined with neck ultrasonography has the highest sensitivity in monitoring differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3668-3673.

53. Pacini F., Capezzone M., Elisei R., et al. Diagnostic 131-iodine whole-body scan may be avoided in thyroid cancer patients who have undetectable stimulated serum Tg levels after initial treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1499-1501.

54. Mazzaferri E.L., Robbins R.J., Spencer C.A., et al. A consensus report of the role of serum thyroglobulin as a monitoring method for low-risk patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1433-1441.

55. Leboulleux S., Girard E., Rose M., et al. Ultrasound criteria of malignancy for cervical lymph nodes in patients followed up for differentiated thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3590-3594.

56. Leboulleux S., Schroeder P.R., Busaidy N.L., et al. Assessment of the incremental value of recombinant thyrotropin stimulation before 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging to localize residual differentiated thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1310-1316.

57. Esteva D., Muros M.A., Llamas-Elvira J.M., et al. Clinical and pathological factors related to 18F-FDG-PET positivity in the diagnosis of recurrence and/or metastasis in patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2006-2013.

58. Robbins R.J., Wan Q., Grewal R.K., et al. Real-time prognosis for metastatic thyroid carcinoma based on 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose-positron emission tomography scanning. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:498-505.