CHAPTER 113 Ileostomy, Colostomy, and Pouches

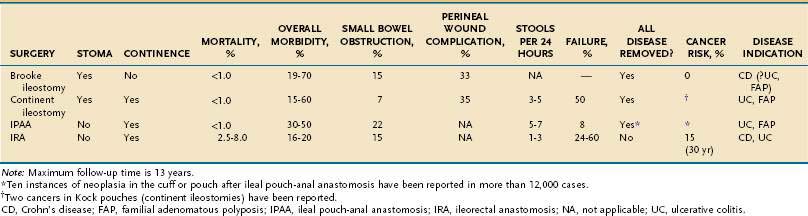

Proctocolectomy and permanent ileostomy return most patients with chronic ulcerative colitis (UC) to excellent health and remove premalignant mucosa in patients with UC or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Many of the inconveniences and dangers formerly associated with an ileal stoma have been eliminated by improved surgical techniques, a wider range of better stomal appliances, and more effective education of patients.1

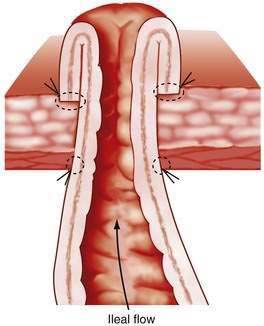

Between 1930 and 1950, the metabolic consequences of ileostomy became apparent, as did the frequent mechanical complications caused by ileostomy dysfunction. Better understanding of fluid, electrolyte, and blood replacement lessened the former problem, and newer techniques of ileostomy construction mitigated the second.2,3 Before these advances, ileostomies were made by withdrawal of the intestine through the abdominal wall, the serosal surface of ileum then being sutured to the skin. Ileostomy dysfunction resulted from the serositis following exposure of the serosal surface to the stomal effluent. The mucosa of the ileum, however, is not susceptible to inflammation after a similar exposure, and a solution, therefore, became conceptually simple: evert the mucosal surface of the bud and suture the mucosa to the skin. This modification was described simultaneously early in the 1950s in the United Kingdom and United States and is commonly referred to as a Brooke ileostomy (Fig. 113-1).1 Development of new ileostomy appliances quickly led to better acceptance by patients and, ultimately, to excellent long-term results.4 Enterostomal therapy was introduced in the 1960s as an additional allied health support, and ileostomy societies have blossomed in most countries, providing a lay component of support to patients with stomas.

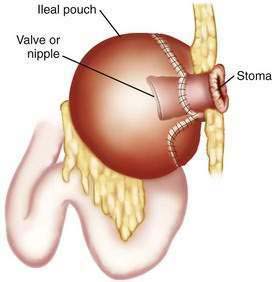

Brooke ileostomies are incontinent by definition, and during the 1960s, Nils Kock, a Swedish surgeon, developed the first effective alternative to this incontinent ileostomy.5 The Kock pouch procedure featured an ileal pouch, a nipple valve, and an ileal conduit, which led to a cutaneous stoma that, because this ileostomy was continent and therefore an appliance was not needed, could be made flush with the skin. The Kock pouch was used in selected patients with chronic UC and FAP.6

Stimulated by patients’ poor acceptance of the ileostomy, surgeons explored other alternatives to the incontinent ileal stoma with its ever-present external appliance. The ileoanal pull-through operation was resurrected, with an important technical modification: the addition of an ileal reservoir.7,8 This procedure offered the advantages of a normal exit for stool and preservation of the anal sphincters. Indeed, the use of this procedure in thousands of patients has revealed ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) to be the procedure of choice in most patients requiring proctocolectomy for chronic UC or FAP.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC CONSEQUENCES OF PROCTOCOLECTOMY

FECAL OUTPUT AFTER PROCTOCOLECTOMY

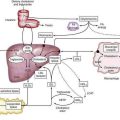

After a colectomy with any type of ileostomy, the absence of the colon obviously prevents its reabsorption of electrolytes and water. Usually, this creates no major pathophysiologic disturbance, but some important principles should be remembered. A normal colon absorbs at least 1000 mL of water and 100 mEq of sodium chloride each day, and the healthy colon can increase absorption more than 5 L/day when presented with increased amounts of fluid.9,10

Also, the colon has a greater capacity than the small intestine to conserve sodium chloride when a person is salt depleted. For example, under conditions of extremely low salt intake, sodium losses in normal stool can be reduced to 1 or 2 mEq/day, whereas patients with ileostomies have obligatory sodium losses of 30 to 40 mEq/day.11–13 The majority of patients adapt to these daily losses through minor changes in salt and water intake and physiologic compensation.14

Well-functioning conventional (Brooke) ileostomies discharge 300 to 800 g of material daily, 90% of which is water.12,13 Continent ileostomies and IPAAs have similar volumes of effluent.15 Foods containing substantial unabsorbable residue increase the total ileostomy output by increasing the amount of solids discharged. Although many anecdotes are reported on the effect of foods on the volume and consistency of stomal effluents, the response to specific foods varies from one patient to another, and changes usually are minimal.16

FUNCTIONAL SEQUELAE

When oral intakes of sodium, chloride, and fluid are adequate, patients with ileostomies do not become depleted in volume or electrolytes; negative sodium balance, however, can follow periods of diminished oral intake, vomiting, or excess perspiration.17 In addition, chronic oliguria is to be anticipated, even with established ileostomies, because normal stools contain approximately 100 mL of water, whereas ileostomies lose 500 to 600 mL/day.14 Patients with ileostomies also have lower urinary Na+/K+ ratios because of compensatory renal conservation of sodium and water. These changes in the composition of urine presumably contribute to the increased frequency of urolithiasis (about 5%) in patients with ileostomies, whose stones are predominantly composed of urate or calcium salts18; these patients have relatively narrow tolerances for change in their volume and electrolyte status, and even minor changes potentially result in life-threatening electrolyte disturbances.19

When the terminal ileum is resected and a proximal ileostomy is constructed, there can be abnormalities of bile acid reabsorption, malabsorption of vitamin B12 (see Chapters 64, 100, and 101), steatorrhea, and more than expected losses of fluid (1 L/day). These abnormalities usually do not follow a colectomy that is performed for chronic UC or FAP because the ileum, being free of disease, is preserved. Resection for Crohn’s colitis can require removal of additional diseased ileum with the possible consequences of malabsorption and even short bowl syndrome, depending on the length of small bowel removed (see Chapters 101, 103, and 111).

Colectomy also reduces the exposure of bile acids to the metabolic effects of the fecal flora, and after ileostomy, secondary bile acids largely disappear from bile; no metabolic consequences of significance have been recognized in this situation.20,21 The flora of ileostomy effluents have quantitative (104 to 107 colony-forming units [CFUs] per 100 milliliters) and qualitative characteristics that are intermediate between those of feces and those of normal ileal contents, whereas the flora in an IPAA or Kock pouch are more similar to feces.22–24

The principal pathophysiologic sequelae of colectomy with ileostomy are mainly the potential consequences of a salt-losing state; patients should be advised to use salt liberally and to increase their fluid intake, especially at times of stress, in hot weather, and after vigorous exercise. A balanced salt solution (Gatorade or Powerade) is a good source of balanced electrolytes. The limited ability of the small intestine to absorb sodium and water, however, means that stomal volumes also increase when the oral intake is increased.13

CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES OF PROCTOCOLECTOMY

After successful proctocolectomy, life expectancy is slightly below normal for the first few years owing to complications of the stoma and to intestinal obstruction; after ileorectostomy for FAP or chronic UC, particularly the former, cancer can develop in the retained rectum. In general, however, the long-term mortality rate in patients after proctocolectomy and conventional ileostomy is the same as for a matched normal population.25 Ninety percent of patients with conventional ileostomies who responded to a survey rated the results of their operation excellent and claimed little inconvenience.4 Overall, there is no real difference in the reported quality of life of patients with conventional ileostomies, continent ileostomies, or an ileal pouch.26 Almost all were able to lead normal lives and enjoy normal sexual relationships; a few patients avoided certain strenuous physical activities.

The metabolic consequences of a proctocolectomy per se should be the same regardless of whether a conventional ileostomy or an alternative procedure is performed. Patients in whom an ileostomy alternative achieves an excellent result have a better quality of life than do patients with a stoma because the former do not need to wear an ileostomy appliance. Indeed, when the Brooke ileostomy and IPAA were compared, patients with IPAA experienced significant advantages in performing daily activities and appeared to enjoy a better quality of life.27 There are certain unique complications of the newer operations, however, including incontinence (Kock pouch), pelvic infections and sepsis, and pouchitis (IPAA), which are discussed later.

THE CONVENTIONAL BROOKE ILEOSTOMY

Prestomal ileitis is a much less common problem than is stomal obstruction. Patients with this complication exhibit the features of mechanical obstruction, and, in addition, they have signs of systemic toxicity (e.g., fever, tachycardia, anemia).28,29 In prestomal ileitis, the ileum has numerous punched-out ulcers, sometimes extending to the serosa. It is not clear whether prestomal ileitis has a different pathogenesis from the changes that follow simple mechanical obstruction of the stoma; both complications involve ileum that was normal histologically at the time of colectomy. Backwash ileitis, seen typically in chronic UC, does not predispose to either prestomal ileitis or obstruction. Conversely, patients who have had colectomy and ileostomy for Crohn’s disease experience problems with the ileal stoma more often, perhaps because transmural inflammation involves the new terminal ileum. In some instances, it is difficult to determine whether stomal dysfunction results from mechanical obstruction or recurrent Crohn’s disease.

Most people with an ileostomy lead a normal life and eat a normal diet; poorly digestible foods (e.g., nuts, corn, some fruits, lightly cooked vegetables) can obstruct the stoma and should be eaten in moderation and with careful chewing.4 Some patients experience continuing difficulties managing their ileostomy. These problems vary in severity, some being minor inconveniences and others being significant drawbacks to the success of the operation. Mechanical difficulties because of a poorly fitting stomal appliance can cause excoriation of the skin around the ileostomy and can even erode the stoma to produce a fistula. Some patients complain of unpleasant odors arising from the ileostomy bag, especially after eating certain foods, such as onions and beans. Because most odor arises from bacterial action on the contents of the appliance, however, the problem may be offset by frequent emptying of the appliance or by adding sodium benzoate or chlorine tablets to the appliance. Oral bismuth subgallate also controls odor, but doubts exist as to whether its long-term use is justified, because questions of neurotoxicity and encephalopathy have been raised.30,31

A review of the long-term outcomes associated with ostomies has demonstrated a high rate of complications. The most common problems related to ostomies are skin irritation and parastomal hernias, both of which contribute to difficulty with appliance pouching, a term used by enterostomal therapists and referring to the fitting of an ostomy device. Several risk factors are associated with development of parastomal hernias, including obesity, malnutrition, chronic respiratory disorders that are associated with increased intra-abdominal pressure, chronic use of glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressive agents, malignancy, advanced age, and wound infection.32–35 Several techniques have been described for parastomal hernia repair, including primary fascial repair, stoma relocation, and mesh repair; mesh repair achieves the best outcomes.32 The simplest approach, primary repair, is associated with very poor outcomes and up to 100% recurrence rates. Stoma relocation may be an effective approach when the initial stoma site is unsatisfactory, but parastomal hernias occur at the new site in up to 76% of patients.35 The use of prosthetic mesh for parastomal hernia repair has significantly improved outcomes, with recurrence rates reported as low as 10%.36,37 To address the concerns of possible mesh infection and erosion of mesh into the bowel, the use of biologic materials, such as human acellular dermal matrix, has been reported, with results that are comparable to mesh in small series.38

Trained stomal therapists and lay societies of ileostomy patients can help with numerous aspects of postoperative care. Education of the patient is best started before surgery; meetings with others who have undergone ileostomy and referral to specialized publications can allay many fears and uncertainties. The United Ostomy Associations of America (UOAA, P.O. Box 66, Fairview, TN 37062-0066; www.uoaa.org) publishes an excellent series of booklets dealing with all aspects of life for the ostomy patient. These materials also are of great help to patients and nursing staffs in the absence of a registered enterostomal therapist (wound ostomy and continence nurse [WOCN]). The location of a registered therapist can be obtained from the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN Society National Office, 15000 Commerce Parkway, Suite C, Mt. Laurel, NJ 08054; www.wocn.org).

CONTINENT ILEOSTOMY (KOCK POUCH)

Clearly, one of the major (social) drawbacks to ileostomy could be eliminated if a continent stoma were possible. Nils Kock reasoned that a pouch and nipple valve constructed of terminal ileum could store ileal content internally until emptied voluntarily by the patient passing a large, soft catheter into the pouch several times daily, thereby obviating the need for an external appliance (Fig. 113-2). The first such operations were reported in 1969, and the results were promising; however, the nipple valve sometimes failed, usually because it slipped out of the pouch, resulting in incontinence.5 Techniques gradually improved, and the most recent approaches have been more successful, providing continence in most patients. In two series, more than 90% of patients were continent for gas and feces (i.e., never requiring an appliance).34,39

This high success rate, however, is achieved at the price of additional operations in most patients for nipple or pouch dysfunction, fistula, or stricture. Wasmuth and colleagues reported a 50% rate of reoperation by 14 years after continent ileostomy construction.40 Furthermore, in a series reported by Lepisto, 59% of patients with a continent ileostomy required reoperation, with a total of 85 pouch reconstructions being performed: 42 patients had one reconstruction, nine had two reconstructions, three had three reconstructions, one had four reconstructions, and two had six reconstructions.41 Others have reported similar findings: patients generally did well after initial continent ileostomy construction, but a sizable minority required repeated surgical intervention either to salvage pouch function or remove the pouch.42,43

Despite requiring numerous reoperations, the majority of Kock pouch patients are satisfied with the outcomes of their functioning pouch. In a recent comparative study on quality of life in patients with standard ileostomies, ileal pouch, and Kock pouch, the Kock pouch patients did not fare significantly better or worse than those with a conventional ileostomy or IPAA; 56% of the continent ileostomy patients, however, did require reoperation to maintain function of the continent ileostomy.26

The fundamental mechanical problem of the nipple valve design in the Kock pouch has prevented widespread acceptance of the procedure. Another continent ileostomy, the T pouch, has been developed to combat this problem44; its design prevents slippage of the intussusceptive nipple valve constructed in the traditional Kock pouch. In the T pouch, the valve mechanism is made by securing an isolated distal ileal segment into a serosal-lined trough formed by the base of two adjacent ileal segments. The high volume-low pressure reservoir is fashioned around this isolated valve segment. Once constructed, the distal end of the valve mechanism is brought up through the skin as a stoma. T pouches have been constructed in only a few patients, and the results are promising, but long-term follow-up is required to assess the structural integrity and clinical success of the new valve design. Given the wide acceptance of the IPAA, continent ileostomy operations are performed rarely and used mainly in patients who have had a proctocolectomy and ileostomy and who desire enteric continence.

ILEAL POUCH-ANAL ANASTOMOSIS

IPAA is now the procedure of choice for most patients who require proctocolectomy for chronic UC or FAP. IPAA is not considered suitable for patients with Crohn’s disease, although this recommendation now is being questioned.45,46 The operation has several major advantages: nearly all mucosal disease is removed in contrast to ileorectostomy; the normal route for elimination is maintained (a permanent stoma is not required); the anal sphincters are undisturbed; and the pelvic dissection, being less extensive than in cancer operations, should not endanger innervation of the sexual organs.

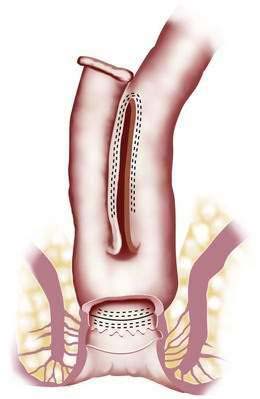

The general principle of ileoanal anastomosis was first described in 1947, and its revival was influenced by the success of pediatric surgeons in children with Hirschsprung’s disease.7 Early approaches used a straight pull-through and sutured the ileum directly to the anal verge.47 Although results in children were encouraging, excessive stool frequency and anal seepage were unacceptable to many adult patients. Subsequently, the operation was modified to include one of several forms of ileal pouch. The basic surgical steps are as follows: a proctocolectomy is performed; the distal rectal mucosa is divided at the top of the anal canal, which leaves a small cuff of residual rectal and anal canal mucosa; an ileal pouch is fashioned and then stapled or sutured to the cuff of remaining rectal and anal canal tissue. A diverting ileostomy is usually required for two to three months until the anastomosis heals completely. At a second operation eight to 12 weeks later, the diverting ileostomy is closed.

The Mayo Clinic has acquired considerable experience with IPAA, having performed more than 2200 of these operations.48–50 Although pouches of different configurations have been advocated by various surgical groups in the past, the pouch routinely used today is the J pouch because of its ease of construction and reliable function (Fig. 113-3).

LONG-TERM RESULTS

IPAA is a complex operation and complications occur frequently. The overall morbidity rate still hovers between 25% and 30%.49–51 Failure, however, is rare, even in those who suffer a postoperative complication.

At the Mayo Clinic, overall pouch success rate was 92% in patients who had had their IPAA for up to 20 years.52 In this series of 1885 IPAA operations performed for UC over a 20-year period with a mean follow-up of 11 years, the overall rate of pouch success at 5, 10, 15 and 20 years was 96.3%, 93.3%, 92.4% and 92.1%, respectively. Over time, the mean daytime stool frequency increased from 5.7 times at one year to 6.4 times at 20 years; nighttime stool frequency also increased from 1.5 to 2.0. The incidence of frequent daytime fecal incontinence increased from 5% to 11% during the day (P < 0.001) and from 12% to 21% at night (P < 0.001). This series demonstrated that IPAA is a reliable surgical procedure for patients requiring proctocolectomy for UC and indeterminate colitis. Furthermore, it showed that the clinical and functional outcomes are excellent and durable.

Complications

Pelvic sepsis, an ominous development, occurs in 5% to 24% of patients after IPAA.49,50,53,54 Computed tomography (CT) is useful for demonstrating pelvic fluid collections or phlegmon. Patients with pelvic phlegmon usually respond to conservative treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics and bowel rest, whereas patients with a pelvic abscess ideally should undergo CT-guided drainage, if technically feasible, or laparotomy and drainage (Fig. 113-4). The most commonly cited risk factor for pelvic sepsis is chronic or high-dose glucocorticoid use in the perioperative period.55 Pelvic sepsis can, in the short-term, lead to pouch excision, which fortunately is rare; long-term functional results of the pouch are worse, however, and there is a higher rate of pouch loss compared with patients who did not experience pelvic sepsis.52

A diverting temporary ileostomy, while minimizing the impact of pelvic sepsis, is associated with a number of complications.56 Closure of temporary ileostomies also may be associated with complications. Peritonitis occurred in 4% of patients and postoperative intestinal obstruction in 12% of patients. Proximal and distal serosal tears during stoma mobilization, in addition to anastomotic leaks, are important causes of peritonitis. If all extraperitoneal bowel (afferent and efferent limbs and the stoma itself) is resected, however, the chance of leaving an unrecognized perforation is nearly eliminated.

Almost all patients have a web-like stricture of the ileoanal anastomosis before ileostomy closure (Fig. 113-5). This stricture generally can be dilated digitally without difficulty, but narrowing can recur and is the most common indication for surgical intervention after an IPAA.57 If the pouch retracts under anastomotic tension, heavy scarring can result in a long, fibrotic stricture. This type of stricture is manifested by increased straining to empty the pouch, a sensation of incomplete pouch evacuation, or a high stool frequency (more than 10 to 12 stools per day). Repeated anal dilation can prevent progression of the stricture.

Clinical Results

Following an IPAA, the average stool frequency is six stools during the day, with one stool at night.48–5054 Daytime and nocturnal stool frequency and the ability to discriminate flatus from stool remain relatively stable over time, whereas the need for stool bulking and hypomotility agents declines. The lower stool frequencies six months after surgery compared with the frequency in the early postoperative period are likely attributable to increased pouch capacity over time.

In the Mayo Clinic experience, major fecal incontinence (more than twice per week) occurs in 5% or less of patients during the day and 12% of patients during sleep.50 In contrast, minor episodes of nocturnal incontinence occur in up to 30% of patients at least one year after the operation. A pad must be worn by 28% of patients for protection against seepage. Minor perianal skin irritation is reported by 63% of patients. Patients older than 50 years have a higher daytime stool frequency (eight per day) than do patients younger than 50 years (six per day). Men and women have similar stool frequencies postoperatively, but women have more episodes of fecal soilage during the day and night; this is thought to be related to a shorter average anal canal length in women. Seventy-eight percent of patients report excellent continence one year after surgery, which remains unchanged at 10 years; 20% experience minor incontinence; and 2% have poor control. Of patients with minor incontinence at one year, 40% remain unchanged, 40% improve, and 20% worsen by 10 years.52 Nocturnal fecal spotting increases during the 10-year period, but not significantly.

Pouchitis and Cuffitis

A wide range of reported incidences suggests that the level of clinical suspicion and the diagnostic criteria for pouchitis vary greatly.58–60 An early experience in IPAA patients demonstrated that patients who have preoperative extraintestinal manifestations of UC had significantly higher rates of pouchitis than patients without such manifestations (39% with preoperative symptoms and 26% without).58 A recent study by Hoda and colleagues, however, demonstrated that whereas extraintestinal manifestations might indicate a predisposition to episodes of acute pouchitis, they are not predictors of chronic pouchitis.60 Furthermore, they report that patients at highest risk for developing chronic pouchitis suffered from postoperative complications, more specifically anastomotic and septic complications.

Other investigators have suggested that there is a biological predisposition for pouchitis and that better risk stratification can be obtained by the preoperative use of serum markers of IBD.61–63 In the study by Hui and colleagues, 63% of patients who went on to develop chronic pouchitis had a positive perinuclear-staining antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) preoperatively, and only 17% had negative serologic results.61 There remain questions about these findings, because not all authors have demonstrated such a relationship.64 Furthermore, although the serologic information is intriguing, it is unclear if it provides any information that would change surgical decision making before surgery, because the surgical options are limited.

As more surgeons have begun to perform a double stapled anastomosis, as opposed to a mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis, there is a remnant cuff of rectal mucosa. This cuff of epithelial tissue can experience intermittent or chronic activity of UC, which has been termed cuffitis.65 Cuffitis can cause symptoms similar to pouchitis. In a study of 61 IPAA patients with symptoms of pouchitis, 7% had cuffitis.66

Most patients with apparent pouchitis or cuffitis have intermittent symptoms or respond well to therapy. In a few, however, symptoms are severe and persistent enough to lead to surgical removal of the pouch. Patients present with increased volumes of output, bleeding, discomfort from the pouch, and general symptoms similar to those of the initial disease. Fever, anemia, and dehydration as a result of diarrhea are variably present; fecal incontinence also is common. Extraintestinal dermatologic and rheumatologic manifestations are seen occasionally.58

In a patient with pouchitis, endoscopy shows the pouch mucosa to be reddened, swollen, and often ulcerated. The mucosa is friable and bleeds readily from minor trauma during endoscopy; inflammatory changes usually are confined to the pouch but also can be seen in the adjacent ileum. Biopsy specimens show a range of acute and chronic inflammatory changes depending on severity, and a pouchitis disease activity index combining clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features has been developed (Table 113-1).59 Gradual escalation of medical therapy for acute or chronic pouchitis is now the standard of care.67 Exclusion of possible etiologies that may require specific treatment is essential before initiating treatment for pouchitis. The following points must be remembered: Patients with ileal pouches are not immune to superimposed specific enteric infections; stool culture and microscopy for parasites are appropriate.

| CRITERIA | SCORE |

|---|---|

| Clinical | |

| Postoperative Stool Frequency | |

| Usual | 0 |

| 1 or 2 stools/day more than usual | 1 |

| ≥3 stools/day more than usual | 2 |

| Rectal Bleeding | |

| None or rare | 0 |

| Present daily | 1 |

| Fecal Urgency or Abdominal Cramps | |

| None | 0 |

| Occasional | 1 |

| Usual | 2 |

| Fever (>100°F) | |

| Absent | 0 |

| Present | 1 |

| Endoscopic | |

| Edema | 1 |

| Granularity | 1 |

| Friability | 1 |

| Loss of vascular pattern | 1 |

| Mucoid exudate | 1 |

| Ulceration | 1 |

| Histologic | |

| Polymorphonuclear Leukocyte Infiltration | |

| None | 0 |

| Mild | 1 |

| Moderate + crypt abscess | 2 |

| Severe + crypt abscess | 3 |

| Percent of Mucosa That Is Ulcerated per Low-Power Field (Average) | |

| <25 | 1 |

| 25-50 | 2 |

| >50 | 3 |

The total score is the sum of the individual scores.

* Pouchitis is defined as a total score of 7 or greater.

Adapted from Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, et al. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: A pouchitis disease activity index. Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69:409.

Pathogenesis

Histopathology of healthy and diseased pouches has shown that chronic inflammation is usual, even when the patient is asymptomatic.68,69 Villus architecture is distorted, and colonic metaplasia is present in biopsies from most pouches, even in the absence of severe acute inflammation. Thus, these changes are considered natural sequelae of the altered anatomy, just as the histologic changes of experimental and clinical blind-loop syndrome have been attributed to bacterial overgrowth.

Other possible causes of pouchitis have little support, including damage by bile acids or their bacterial metabolites and lack of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).59 Normal colonic mucosa uses SCFAs as a source of nutrition, and some authors have proposed that IBD can result when the colon is deprived of SCFAs.70 The clearest clinical experiment that tests this hypothesis is diversion colitis. Harig and coworkers proposed that diversion colitis is caused by deprivation of SCFAs,71 support for which is provided by the observation that diversion colitis improves in response to SCFA enemas. Ileal pouches contain high concentrations of SCFAs (≥100 mmol), however, and so a state of deprivation seems unlikely. Indeed, pouchitis has worsened or shown no predictable response to SCFA enemas.72 In a detailed evaluation of luminal factors, including fecal concentrations of bacteria, bile acids, and SCFAs, there were no differences between patients with or without pouchitis.59 Alteration in butyrate metabolism has been linked to pouchitis.73

At present, there is no definitive cause for pouchitis, but it most likely does involve an interaction between the pouch microenvironment and the patient’s underlying immune response to that environment. In the Mayo Clinic experience in patients who have had their IPAA for nearly 20 years, the rate of having at least one episode of pouchitis was 48% at 10 years, and it rose to 78% at 20 years.52 In this cohort, less than 5% of patients developed chronic pouchitis, and only 2% required pouch removal or permanent diversion.

Treatment

If diarrhea alone is the major complaint, treatment with simple antidiarrheal measures may be all that is required. For more severely symptomatic patients, a variety of empiric treatments have emerged. When the condition was first encountered in continent ileostomies, anecdotal evidence was that constant drainage would help, based on the assumption that stasis was an important predisposing factor.23 Stasis should be a lesser factor after IPAA, although incomplete emptying (e.g., with the S pouch) or a persistent anastomotic stricture might need to be excluded. Metronidazole, 500 mg twice daily for 28 days, has been used often as a first line of treatment. The response to metronidazole or other broad-spectrum antibiotics usually is dramatic. Some patients relapse after initial therapy with antibiotics, and they require subsequent courses of treatment. In general, antibacterial agents with a spectrum of activity against anaerobes have been most successful in treating pouchitis.

Sequelae

Although the prevalence of chronic pouchitis is low, the possible consequences of chronic inflammation of the neorectum, especially dysplasia and malignant change, arouse concern. Morphologic and biochemical changes occur in the ileal mucosa of pouches, including villus blunting, chronic inflammatory infiltrates, variable transition to production of a colonic type of mucus (sulfomucins), and increased cellular proliferation.74 Observations based on long-term follow-up (mean of 6.3 years) reveal three patterns of mucosal adaptation: approximately one half of the patients showed mild villus atrophy and minimal inflammation, slightly fewer had transient moderate or severe atrophy and inflammation with intervals of recovery, and approximately 10% had permanent subtotal or total villus atrophy with chronic inflammation.68 In this study, three of eight patients developed low-grade dysplasia; in one patient it developed two years postoperatively. In patients having a double-stapled anastomosis, the remaining rectal cuff and anal canal transition zone tissue represent at-risk tissue. In one series of 225 patients with a stapled IPAA, 238 rectal cuff and anal canal biopsies were obtained; 202 (84.9%) had histologically confirmed chronic inflammation, 11 (4.6%) had acute inflammation, and 25 (10.5%) were read as normal.75 Interestingly, 9 of the 11 patients with acute inflammation were asymptomatic.

Pouch Failure

Large series have reported failure rates between 2% and 12%, and in the Mayo clinic series, 8% of patients ultimately required pouch excision or construction of a permanent ileostomy.52 The most common causes of pouch failure, either alone or in combination, include pelvic sepsis, high stool volumes, Crohn’s disease, and uncontrollable fecal incontinence; pouchitis is the sole cause in 2% of all patients. Of the patients in whom the pouch fails, failure occurs within 1 year in 75%, by 2 years in 12%, and by 3 years in 12%. Fortunately, pouch failure is relatively uncommon. Early failures are almost always related to technical issues or complications related to the original operation, whereas late failures are more commonly related to chronic pouchitis or Crohn’s disease in the pouch.

Quality of Life

In one study of quality of life after a Brooke ileostomy or IPAA for UC and FAP, patients were highly satisfied with either operation (Brooke ileostomy, 93%; IPAA, 95%).27 Daily activities (e.g., sexual life, participation in sports, social interaction, work, recreation, family relationships, travel), however, were more likely to be adversely affected with a Brooke ileostomy than by IPAA.

Sexual Dysfunction

Impotence and retrograde ejaculation developed in 1.5% and 4% of men, respectively. Dyspareunia developed in 7% of women postoperatively.49,50 Early studies of IPAA focused on physiologic assessment, but recent studies have concentrated on more multidomain quality-of-life assessments. A prospective evaluation of sexual function in patients with IPAA was performed using validated survey instruments, including the International Index of Erectile Function in men and the Female Sexual Function Index in women. Overall quality of life was assessed using the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire. Preoperative scores were compared with scores at six and 12 months postoperatively. Of the 59 patients who completed the study, male sexual function and erectile function scores remained high 12 months after surgery and female sexual function improved 12 months after surgery. Quality of life significantly improved after IPAA in both men and women.76 Others have reported similar improvements after IPAA.77,78

CONTROVERSIES

Double-Stapled versus Hand-Sewn Anastomosis

To determine if stapled IPAA conferred any advantage over hand-sewn IPAA, we conducted a randomized study at the Mayo Clinic in which 41 patients were randomized to double-stapled (17 patients) or hand-sewn (15 patients) technique.79 In the stapled group, 1.5 to 2.0 cm of ATZ was preserved, whereas complete mucosectomy was performed in the hand-sewn group. Overall, complications were the same in the two groups. Stool frequency and rates of fecal incontinence during the day and night were similar between the groups; however, fewer patients treated with the double-stapled technique had nocturnal incontinence.

Similar findings have been reported by other groups.80 In a meta-analysis of more than 4000 patients, Silvestri and colleagues concluded that both techniques had similar early postoperative outcomes; stapled IPAA offered improved nocturnal continence, however, which was reflected in higher anorectal physiologic measurements.81

Role of Defunctioning Ileostomy

The most feared complication of IPAA is pelvic sepsis; therefore, a defunctioning ileostomy after pouch construction usually is performed to minimize its occurrence.82 In the literature, the reported rate of pelvic sepsis after IPAA varies between 0% and 25%. Although the incidence of pelvic sepsis is relatively low (6%) at the Mayo Clinic, when it occurs, it is responsible for a significant proportion of the failed pouches.52,57

Proponents of defunctioning ileostomies argue that diverting stomas allow the anal sphincter and ileal mucosa to recover before intestinal continuity is restored and that patients have a short-lived experience of a stoma to fully appreciate the ultimate benefit of IPAA. Use of a loop ileostomy does not appear to protect the patient fully from pelvic sepsis; however, its presence makes it easier to manage a patient with this complication. Supporters of a one-stage procedure believe that an IPAA can be performed without increased risk of pelvic sepsis.83–87 A one-stage procedure avoids an ileostomy and a second hospitalization and operation, lowers the total cost, and results in a shorter hospital stay and perhaps a decreased incidence of small bowel obstruction.

In the large single-surgeon study reported by Sugerman and associates, there were no differences in the complication rates and functional outcomes of patients who had not had a diverting ileostomy compared with those who had a diverting ileostomy; there also was no relationship to glucocorticoid use.83,88 Whereas there might be no significant difference in the complication rate in patients without a diverting ileostomy, one study has suggested that the severity of complications was greater in patients without a protecting ileostomy.89

ADDITIONAL ISSUES

Risk of Cancer

Patients with UC are at risk for developing adenocarcinoma of the colon, which increases with the duration of disease and extent of colonic involvement (see Chapters 112 and 123). Figures suggest that the risk of colon cancer for people with IBD increases by 0.5% to 1.0% yearly, eight to 10 years after diagnosis.90 Any surgery that leaves behind diseased colonic mucosa puts the patient at risk for developing dysplasia or neoplasia in this residual tissue. The risk of developing a carcinoma in the residual colonic mucosa may be directly related to the amount of residual mucosa remaining in situ. Complete excision of the rectal mucosa during IPAA substantially decreases the risk of dysplasia. With the more commonly used stapled IPAA, however, a small amount of residual rectal and anal canal tissue is retained.

Early studies by Tsunoda and colleagues demonstrated the presence of dysplasia in mucosectomy specimens, which they believed supports the use of a mucosectomy and hand-sewn anastomosis.91 Even performing a mucosectomy, however, does not ensure that all rectal and at-risk anal canal mucosa is removed. In one study that evaluated anal canal specimens, islands (rests) of mucosa were present despite “complete” mucosal resection.92 In a study with long-term follow-up, however, the risk of dysplasia was quite low.93 A cohort of 289 patients with stapled IPAAs was followed and had multiple biopsies of the rectal cuff and anal transition zone performed over a 10-year period. Dysplasia was identified in eight patients, including four with low-grade and four with high-grade dysplasia. No cancer in the ATZ was found during the study period. The authors concluded that ATZ dysplasia after stapled IPAA was infrequent and usually self-limiting. ATZ preservation did not lead to the development of cancer in the ATZ with a minimum of 10 years of follow-up, although long-term surveillance is recommended to monitor dysplasia.

Detection of neoplastic change in the pouch itself is another reason to perform follow-up in patients with IPAA. A subgroup of patients has been identified in whom the mucosa of the pelvic pouch develops severe villus atrophy.68 These patients seem to have a significantly higher incidence of dysplasia compared with patients without villus atrophy (71% vs. 0%). The former group may be at greater risk for developing carcinoma and might require more intensive follow-up with regular pouch endoscopy and biopsy. Despite these findings, dysplasia in a pouch is a rare event. In group of 45 patients followed for a median of six years (one to 28 years), dysplasia of any type was found in 4% of pouch biopsies and there was no evidence of malignancy.94

To date, there have been a small number of case reports of carcinomas arising in ileal pouches or in the region of the anastomosis.95–98 Surprisingly, many of these cancers have arisen in patients who have undergone a complete mucosectomy with hand-sewn anastomosis. In a recent review, Branco and colleagues found that the occurrence of adenocarcinoma following IPAA for UC is an infrequent event.99 Their conclusions were that post-IPAA cancer can occur following either mucosectomy or stapled anastomosis; that this malignancy can occur after IPAA performed for UC either with or without neoplasia; and that this complication is seen whether or not the initial cancer or dysplasia had involved the rectum. Given the known occurrence of dysplasia in pouch mucosa and the rare reports of cancers arising in pouches, routine clinical and endoscopic surveillance should be performed in patients after their IPAA.

Fertility and Pregnancy

Many patients with UC are in their childbearing years. Therefore, the impact of surgery on fertility is an important consideration when discussing surgery with a young woman. A number of studies have evaluated fertility and the course of a subsequent pregnancy after surgery.100,101 Patients who have had a proctocolectomy and end ileostomy or Kock pouch can expect to have a normal pregnancy and delivery; however, these women often have temporary stoma or Kock pouch dysfunction.102 A similar disturbance of pouch function is seen in IPAA patients, in whom a slight increase in stool frequency, incontinence, and pad use is reported during the pregnancy.100,101 Fortunately, this is temporary, and patients return to their baseline pouch function after the pregnancy. There is a reported higher rate of cesarean sections in IPAA patients, but there appears to be no contraindication to vaginal delivery, and the decision to proceed to a cesarean section should be based upon obstetric considerations.

Previous studies evaluated the course of pregnancies after IPAA, but the specific issue of fecundity after IPAA had not been considered. A Swedish population-based study, however, demonstrated a significant reduction in fecundity after IPAA.103 More important, of the post-IPAA patients who became pregnant, 29% of pregnancies occurred only after in vitro fertilization compared with the expected 1% of all births in Sweden during the study period. The basis of this decreased fertility is unknown, but the authors hypothesize that changes in pelvic anatomy resulting from removal of the rectum and scarring from the pelvic dissection are major contributors to the problem. A case-control study comparing women with IPAAs and female controls who had previous abdominal surgery found that women who had an IPAA had significantly more infertility evaluations and need for infertility treatments.104 Furthermore, an analysis of infertility treatments for post-IPAA women demonstrated that they suffered a reduction in the probability of conception rather than complete infertility. This reduction in fecundity is not seen in women who have undergone ileorectal anastomosis for FAP, which further the supports the idea that postoperative adhesions or altered pelvic anatomy contribute to this problem.105

Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis and Indeterminate Colitis

Among 1519 consecutive patients with UC undergoing IPAA between January 1981 and December 1995, 82 patients (5%) had features of indeterminate colitis, including unusual distribution of inflammation, deep linear ulcers, neural proliferation, transmural inflammation, fissures, and creeping fat.106 We found that 12 (15%) of the 82 patients with indeterminate colitis eventually developed Crohn’s disease during follow-up, compared with only 26 (2%) of 1437 patients with UC. The probability of remaining free of Crohn’s disease at 10 years was 98% in patients with UC and 81% in the indeterminate colitis patients. After IPAA, patients with indeterminate colitis who did not develop Crohn’s disease experienced long-term outcomes nearly identical to those of patients with UC; that is, nearly 85% had functioning pouches 10 years after the operation. Crohn’s disease, however, regardless of whether it develops and is diagnosed after IPAA operations for UC or indeterminate colitis, is associated with poor long-term outcomes. Similar to our findings, other institutions have shown that although pouch complications are higher in patients with indeterminate colitis, the functional results after IPAA for indeterminate colitis are identical to those after UC.107

Impact of Biological Medical Therapy

The inclusion of newer biological therapies, such as infliximab, in the treatment of UC has raised concerns regarding their impact on the surgical outcomes after IPAA. In a study by Selvasekar and colleagues, 47 UC patients received preoperative (IPAA) infliximab therapy and 254 did not.108 Patients who received infliximab were statistically more likely to have postoperative infectious complications and pelvic abscesses. After multivariate adjustment for disease severity and other medication use, infliximab remained independently associated with an increased risk of ileal pouch-related and infectious complications. Another study of 85 patients with UC who received infliximab preoperatively found that they were at increased risk for postoperative septic complications as well as late complications compared with patients who did not receive infliximab.109 The authors noted that patients who received infliximab were more likely to have undergone a three-stage IPAA, likely due to surgeon reluctance to perform an IPAA in the setting of preoperative infliximab administration.

As previously discussed, pelvic sepsis and abscess are devastating postoperative complications and are the leading risk factor for ileal pouch loss.52 Given the uncertainty about the role of biologic therapy contributing to this problem or the possibility of much sicker patients presenting for surgery, a three-stage approach in patients who have received preoperative infliximab may be considered.

ABDOMINAL COLECTOMY AND ILEORECTAL ANASTOMOSIS

The aim of a colectomy with an ileorectal anastomosis (IRA) is to extirpate most of the diseased colonic mucosa, thus reducing the risks of hemorrhage, megacolon and its complications, and malignant degeneration, while allowing the rectum to retain continence for stool and gas. The rationale for an IRA is that the operation avoids a permanent stoma, minimizes or eliminates injury to the pelvic nerves, and is easy to perform. Other operations, if they become necessary, are not precluded.110–113 The rationale against the operation, however, is nearly as convincing. Subsequent proctectomy is required in 6% to 37% of patients, poor results have been reported in up to 50%, and the risk of developing carcinoma in the retained rectum approaches 17% after 27 years.113,114

In a study by Pastore and colleagues, who reviewed the course of 48 patients with UC and 42 patients with Crohn’s disease who underwent an IRA, 84% of the UC and 91% of the Crohn’s disease patients reported an improvement in their quality of life.115 One patient with UC developed carcinoma of the rectal stump 11.5 years after the colectomy and IRA (cumulative probability of remaining free of cancer, 85.7% at 12 years).

In patients with Crohn’s disease and minimal or no rectal involvement, IRA with excision of the diseased colon is an appropriate operation. In addition, IRA, as a sphincter-saving procedure, continues to have a place in the surgical treatment of UC for high-risk or older patients who are not good candidates for IPAA and have relatively mild disease. It is also important that these patients understand the need for continued screening of the rectum because of possible development of a malignancy. The quality of life after IRA has been reported to be good; patient satisfaction is high, and an active, productive lifestyle can be preserved.115,116

COMPLICATIONS

Operative mortality for elective IRA has been reported to vary between 2% and 8%.116,117 In the series of UC patients reported by Leijonmarck and colleagues, complications occurred in seven of 43 patients (16%) undergoing an elective, one-stage procedure.116 There were two postoperative deaths (4%). Twenty-two patients (43%) had a functioning IRA at the time of follow-up, with a mean time of observation of 13 years. The cumulative probability of having the IRA in function at 10 years was 51%. The causes of total excision were recurrent inflammation in the retained rectum (N = 23), dysplasia (N = 3), and postoperative complications (N = 3). No rectal carcinoma occurred.

LAPAROSCOPIC APPROACH

The most important change in surgical practice related to all of these procedures is the application of laparoscopic techniques. Minimal-access colon surgery began in the early 1990s; however, improvements in image technology and instrumentation have only recently facilitated complex colorectal procedures. Laparoscopic approaches for IPAA were developed to reduce the impact of this procedure on patients who are already physiologically stressed, decrease length of hospital stay, reduce morbidity, and improve cosmesis. The initial reports of laparoscopic IPAA were discouraging, however, because of very long operative times and few observed postoperative benefits.118–120

Subsequent reports, from our institution and others, have clearly demonstrated the benefits of a minimally invasive approach in regard to postoperative decreases in length of stay, need for narcotics, and overall morbidity.121–123 At the Mayo Clinic, the minimally invasive approach has become the preferred surgical operation for IPAA. Indications for operative intervention are not changed by the laparoscopic approach.

In a case-matched series, 40 patients undergoing laparoscopic IPAA (LAP) were matched to open controls. The patients were matched for disease, age, gender, body mass index (BMI), and date of operation. The LAP group exhibited significant benefits in time to ingesting clear liquids (1 vs. 3 days; P < 0.001), eating a regular diet (3 vs. 4 days; P < 0.001), and regaining bowel function (2 vs. 3 days; P < 0.001).93 Duration of narcotic use was shorter in the LAP group (P < 0.001), and length of stay was reduced (4 vs. 7 days; P < 0.001). LAP patients had longer operative times (270 vs. 192 minutes; P < 0.001), but operative time decreased with experience and now averages 180 to 210 minutes. Subsequent studies within our institution have continued to demonstrate these short-term patient benefits.124

RISK-BENEFIT ANALYSIS

CONVENTIONAL ILEOSTOMY

The Brooke ileostomy is safe and reliable and has broad applicability to patients with IBD who require proctocolectomy. It is not, however, entirely free of complications (Table 113-2). Up to 30% of patients have a septic complication, 20% to 25% require revision of the stoma, 15% have recurrent small bowel obstruction, and stomal dysfunction can occur in up to 30% of cases.

ILEORECTAL ANASTOMOSIS

The primary benefit of an IRA is that the rectum is undisturbed by the operative dissection, the normal pathway of defecation is left in situ, and the incidence of bladder or sexual problems is low. There also is no perineal wound (see Table 113-2). In many patients, the overall functional results are reasonably good.

Farouk R, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. Functional outcomes after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2000;231:919-26. (Ref 50.)

Hahnloser D, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. The effect of ageing on function and quality of life in ileal pouch patients: A single cohort experience of 409 patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2004;240:615-21. (Ref 51.)

Hahnloser D, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. Results at up to 20 years after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 2007;94:333-40. (Ref 52.)

Israelsson LA. Preventing and treating parastomal hernia. World J Surg. 2005;29:1086-9. (Ref 34.)

Larson DW, Cima RR, Dozois EJ, et al. Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileal-pouch–anal anastomosis: A single institutional case-matched experience. Ann Surg. 2006;243:667-72. (Ref 123.)

Olsen K, Joelsson M, Laurberg S, et al. Fertility after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in women with ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:493. (Ref 103-5.)

Pemberton JH, Phillips SF, Ready RR, et al. Quality of life after Brooke ileostomy and ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Ann Surg. 1989;209:620-28. (Ref 27.)

Remzi FH, Fazio VW, Delaney CP, et al. Dysplasia of the anal transitional zone after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: Results of prospective evaluation after a minimum of ten years. Dis Colon Rectum.. 2003;46:6-13. (Ref 93.)

Selvasekar CR, Cima RR, Larson DW, et al. Effect of infliximab on short-term complications in patients undergoing operation for chronic ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:956-62. (Ref 108.)

Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of inflammatory and non-inflammatory sequelae of ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:93-101. (Ref 65.)

Weise WJ, Serrano FA, Fought Gennari FJ. Acute electrolyte and acid-base disorders in patients with ileostomies: A case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:494-500. (Ref 19.)

Yu E-D, Shao Z, Shen B. Pouchitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5598-604. (Ref 67.)

Ziv Y, Church JM, Fazio VW, et al. Effect of systemic steroids on ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:504-8. (Ref 55.)

1. Hill GL. Historical introduction. editor. Hill GL, editor. Ileostomy: Surgery, physiology, and management. 1976. Grune & Stratton, New York: 1

2. Brooke BN. Management of ileostomy including its complications. Lancet. 1952;2:102.

3. Turnbull RB. Symposium on chronic ulcerative colitis: Management of ileostomy. Am J Surg. 1953;86:617.

4. Roy PH, Sauer WG, Beahrs OH, et al. Experience with ileostomies: Evaluation of long-term rehabilitation in 497 patients. Am J Surg. 1970;119:77.

5. Kock NG. Intra-abdominal reservoir in patients with permanent ileostomy: Preliminary observations on a procedure resulting in fecal continence in five ileostomy patients. Arch Surg. 1969;99:223.

6. Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Beart RWJr, et al. Continent ileostomy: The Mayo Clinic experience. In: Dozois RR, editor. Alternatives to conventional ileostomy. Chicago: Year Book; 1985:180.

7. Ravitch MM, Sabiston DC. Anal ileostomy with preservation of the sphincter. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1947;84:1095.

8. Beart RWJr, Metcalf AM, Dozois RR, et al. The J ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: The Mayo Clinic Experience. In: Dozois RR, editor. Alternatives to conventional ileostomy. Chicago: Year Book; 1985:384.

9. Phillips SF, Giller J. Contribution of the colon to electrolyte and water conservation in man. J Lab Clin Med. 1973;81:733.

10. Debongnie JC, Phillips SF. Capacity of the human colon to absorb fluid. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:698.

11. Dole VP, Dahle LK, Cotzias G, et al. Dietary treatment of hypertension: Clinical and metabolic studies of patients on the rice-fruit diet. J Clin Invest. 1950;29:1189.

12. Kramer P. The effect of varying sodium loads on the ileal excreta of human ileostomized subjects. J Clin Invest. 1966;45:1710.

13. Kanaghinis T, Lubran M, Coghill NF. The composition of ileostomy fluid. Gut. 1963;4:322.

14. Clarke AM, Chirnside A, Hill GL, et al. Chronic dehydration and sodium depletion in patients with established ileostomies. Lancet. 1967;2:740-43.

15. Metcalf AM, Phillips SF. Ileostomy diarrhea. Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;15:705.

16. Kramer P, Kearney MS, Ingelfinger FJ. The effect of specific foods and water loading on the ileal excreta of ileostomized human subjects. Gastroenterology. 1962;42:535.

17. Gallagher ND, Harrison DD, Skyring AP. Fluid and electrolyte disturbances in patients with long established ileostomies. Gut. 1962;3:219.

18. Clarke AM, McKenzie RG. Ileostomy and the risk of urinary uric acid stones. Lancet. 1969;2:395.

19. Weise WJ, Serrano FA, Fought Gennari FJ. Acute electrolyte and acid-base disorders in patients with ileostomies: A case series. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:494.

20. Morris JS, Low-Beer TS, Heaton KW. Bile salt metabolism and the colon. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1973;8:425.

21. Gadacz TR, Kelly KA, Phillips SF. The Kock ileal pouch: Absorptive and motor characteristics. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:1287.

22. Gorbach SL, Nahas L, Weinstein L. Studies of intestinal microflora: IV. The microflora of ileostomy effluent: A unique microbial etiology. Gastroenterology. 1967;53:874.

23. Kelly DG, Phillips SF, Kelly KA, et al. Dysfunction of the continent ileostomy: Clinical features and bacteriology. Gut. 1983;24:193.

24. O’Connell PR, Rankin DR, Weiland LH, et al. Enteric bacteriology, absorption, morphology, and emptying after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1986;73:909.

25. Watts JM, de Dombal FT, Goligher JC. Long-term complications and prognosis following major surgery for chronic ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 1966;53:1014.

26. Hoekstra LT, de Zwart F, Guijt M, et al. Morbidity and quality of life after continent ileostomy in the Netherlands. Colorectal Dis. 2008 Aug 21. [Epub ahead of print]

27. Pemberton JH, Phillips SF, Ready RR, et al. Quality of life after Brooke ileostomy and ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Ann Surg. 1989;209:620.

28. Phillips SF. Metabolic consequences of a stagnant loop at the end of the small bowel. World J Surg. 1987;11:763.

29. Knill-Jones RP, Morson B, Williams R. Prestomal ileitis: Clinical and pathological findings in five cases. Q J Med. 1970;39:287.

30. Sparberg M. Bismuth subgallate as an effective means for control of ileostomy odor: A double-blind study. Gastroenterology. 1974;66:476.

31. Report from the Australian Drug Evaluation Committee. Adverse effects of bismuth subgallate. Med J Aust. 1974;2:664.

32. Carne PW, Robertson GM, Frizelle FA. Parastomal hernia. Br J Surg. 2003;90:784.

33. Shellito PC. Complications of abdominal stoma surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1562.

34. Israelsson LA. Preventing and treating parastomal hernia. World J Surg. 2005;29:1086.

35. Allen-Mersh TG, Thomson JP. Surgical treatment of colostomy complications. Br J Surg. 1988;75:41.

36. Hofstetter WL, Vukasin P, Ortega AE, et al. New technique for mesh repair of paracolostomy hernias. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1054.

37. Janes A, Cengiz Y, Israelsson LA. Preventing parastomal hernia with a prosthetic mesh. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1356.

38. Taner T, Cima RR, Larson DW, et al. The use of human acellular dermal matrix for parastomal hernia repair in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A novel technique to repair fascial defects. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(2):349-54.

39. Kock NG, Mynvold HE, Nilsson LO, et al. Continent ileostomy: The Swedish experience. In: Dozois RR, editor. Alternatives to conventional ileostomy. Chicago: Year Book; 1985:163.

40. Wasmuth HH, Svinsa M, Trano A, et al. Surgical load and long-term outcomes for patients with Kock continent ileostomy. Colorectal Disease. 2007;9:713.

41. Lepisto AH, Jarvinen HJ. Durability of Kock continent ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:925.

42. Denoya PI, Schluender SJ, Bub DS, et al. Delayed Kock pouch nipple valve failure: Is revision indicated. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1544.

43. Borjesson L, Oresland T, Hulten L. The failed pelvic pouch: Conversion to a continent ileostomy. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8:102.

44. Kaiser AM, Stein JP, Beart RW. T-pouch: A new valve design for a continent ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:411.

45. Panis Y, Poupard B, Nemeth J, et al. Ileal pouch/anal anastomosis for Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 1996;347:854.

46. Regimbeau JM, Panis Y, Pocard M, et al. Long-term results of ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for colorectal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:769.

47. Stryker SJ, Dozois RR. The ileoanal anastomosis: Historical perspectives. In: Dozois RR, editor. Alternatives to conventional ileostomy. Chicago: Year Book; 1985:225.

48. Pemberton JH, Kelly KA, Beart RWJr, et al. Ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: long-term results. Ann Surg. 1987;206:504.

49. Dozois RR, Kelly KA. J ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: Complications and long-term outcome in 1310 patients. Br J Surg. 1998;85:800.

50. Farouk R, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. Functional outcomes after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2000;231:919.

51. Hahnloser D, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. The effect of ageing on function and quality of life in ileal pouch patients: A single cohort experience of 409 patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2004;240:615.

52. Hahnloser D, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. Results at up to 20 years after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 2007;94:333.

53. Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, et al. Ileal pouch–anal anastomoses complications and function in 1995. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120.

54. Michellassi F, Lee J, Rubin M, et al. Long-term functional results after ileal pouch anal restorative proctolocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: A prospective observational study. Ann Surg. 2003;238:433.

55. Ziv Y, Church JM, Fazio VW, et al. Effect of systemic steroids on ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:504-8.

56. Feinberg SM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z. Complications of loop ileostomy. Am J Surg. 1987;153:102.

57. Galandiuk S, Scott NA, Dozois RR, et al. Ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: reoperation for pouch-related complications. Ann Surg. 1990;212:446.

58. Lohmuller JL, Pemberton JH, Dozois RR, et al. Pouchitis and extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Ann Surg. 1990;211:622.

59. Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, et al. Pouchitis after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: A pouchitis disease activity index. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:409.

60. Hoda KM, Collins JF, Knigge KL, et al. Predictors of pouchitis after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: A retrospective review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:554.

61. Hui T, Landers C, Vasiliauskas E, et al. Serologic responses in indeterminate colitis patient before ileal-pouch–anal anastomosis may determine those at risk for continuous pouch inflammation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1254.

62. Fleshner PR, Vasiliauskas E, Kam LY, et al. High level perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) in ulcerative colitis patients before colectomy predicts the development of chronic pouchitis after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Gut. 2001;49:671-7.

63. Kusisma J, Jarvinen H, Kahri A, et al. Factors associated with disease activity of pouchitis after surgery for ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:544.

64. Aisenberg J, Legnani PE, Nilubol N, et al. Are pANCA, ASCA, or cytokine gene polymorphisms associated with pouchitis? Long-term follow-up in 102 ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:432.

65. Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of inflammatory and non-inflammatory sequelae of ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:93-101.

66. Shen B, Achkar J-P, Lashner BA, et al. Irritable pouch syndrome: A new category of diagnosis for symtomatic patients with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:972.

67. Yu E-D, Shao Z, Shen B. Pouchitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5598.

68. Veress B, Reinholt FP, Lindquist K, et al. Long-term histomorphological surveillance of the pelvic ileal pouch: Dysplasia develops in a subgroup of patients. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1090.

69. Apel R, Cohen Z, Andrews CW, et al. Prospective evaluation of early morphological changes in pelvic ileal pouches. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:435.

70. Roediger WEW. The colonic epithelium in chronic ulcerative colitis—an energy deficiency disease? Lancet. 1980;2:712.

71. Harig JM, Soergel KH, Komorowski RA, et al. Treatment of diversion colitis with short chain fatty acid irrigation. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:23.

72. DeSilva HJ, Ireland A, Kettlewell M, et al. Short-chain fatty acids irrigation in severe pouchitis [letter]. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1416.

73. De Preter V, Bulteel V, Suenaert P, et al. Pouchitis, similar to active ulcerative colitis, is associated with impaired butyrate oxidation by intestinal mucosa. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(3):335-40.

74. DeSilva HJ, Millaro PR, Kettlewell M, et al. Mucosal characteristics of pelvic ileal pouches. Gut. 1991;32:61.

75. Fichera A, Ragauskaite L, Silvestri MT, et al. Preservation of the anal tranisition zone in ulcerative colitis: Long-term effects on defecatory function. J Gastointest Surg. 2007;11:1647.

76. Davies RJ, O’Connor BI, Victor C, et al. A prospective evaluation of sexual function and quality of life after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1032.

77. Larson DW, Davies MM, Dozois EJ, et al. Sexual function, body image, and quality of life after laparoscopic and open ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:392.

78. Gorgun E, Remzi FH, Montague DK, et al. Male sexual function improves after ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:545.

79. Reilly WT, Pemberton JH, Wolff BG, et al. Randomized prospective trial comparing ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) performed by excising the anal mucosa to IPAA performed by preserving the anal mucosa. Ann Surg. 1997;225:666.

80. Silvestri MT, Hurst RD, Rubin MA, et al. Chronic inflammatory changes in the anal transition zone after stapled ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: Is mucosectomy a superior alternative. Surgery. 2008;144:533.

81. Lovegrove RE, Constantinides VA, Heriot AG, et al. A comparison of hand-sewn versus stapled ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) following proctocolectomy: A meta-analysis of 4183 patients. Ann Surg. 2006;244:18.

82. Galandiuk S, Wolff BG, Dozois RR, et al. Ileal pouch–anal anastomosis without ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:870.

83. Sugerman HJ, Sugerman EL, Meador JG, et al. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis without ileal diversion. Ann Surg. 2000;232:530.

84. Heuschen UA, Hinz U, Allemeyer EH, et al. One- or two-stage procedure for restorative proctocolectomy: Rationale for a surgical strategy in chronic ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2001;234:788.

85. Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Milsom JW, et al. Omission of temporary diversion in restorative proctocolectomy: Is it safe? Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:1007.

86. Matikainen M, Santavirta J, Hiltunen K. Ileoanal anastomosis without a covering ileostomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:384.

87. Sugerman HJ, Newsome HH, Decosta G, et al. Stapled ileoanal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis and familial polyposis without a temporary diverting ileostomy. Ann Surg. 1991;213:606.

88. Cohen Z, McLeod RS, Stephen W, et al. Continuing evolution of the pelvic pouch procedure. Ann Surg. 1992;216:506.

89. Williamson MER, Lewis WG, Sagar PM, et al. One-stage restorative proctocolectomy without temporary ileostomy for ulcerative colitis: A note of caution. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1019.

90. Munkholm P. Review article: The incidence and prevalence of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18(Suppl 2):1.

91. Tsunoda A, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ. Incidence of dysplasia in the anorectal mucosa in patients having restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:506.

92. Haray PN, Amamath B, Weiss EG, et al. Low malignant potential of the double-stapled ileal pouch–anal anastomosis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1406.

93. Remzi FH, Fazio VW, Delaney CP, et al. Dysplasia of the anal transitional zone after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis: Results of prospective evaluation after a minimum of ten years. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:6.

94. Borjesson L, Willen R, Haboubi N, et al. The risk of dysplasia and cancer in the ileal pouch mucosa after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative proctocolitis: A long-term follow-up study. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:494.

95. Laureti S, Ugolini F, D’Errico A, et al. Adenocarcinoma below ileoanal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: Report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:418.

96. Hassan C, Zullo A, Speziale G, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the ileoanal pouch anastomosis: An emerging complication? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2003;18:276.

97. Heuschen UA, Heuschen G, Autschbach F, et al. Adenocarcinoma in the ileal pouch: Late risk of cancer after restorative proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16:126.

98. Lee SW, Sonoda T, Milsom JW. Three cases of adenocarcinoma following restorative proctocolectomy with handsewn anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: A review of reported cases in the literature. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:591.

99. Branco BC, Sachar DB, Heimann TM, et al. Adenocarcinoma following ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: Review of 26 cases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:295.

100. Juhasz ES, Fozard B, Dozois RR, et al. Ileal pouch–anal anastomosis function following childbirth: An extended evaluation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:159.

101. Nelson H, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, et al. The effect of pregnancy and delivery on the ileal pouch–anal anastomosis functions. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:384.

102. Gopal KA, Amshel Al, Shonberg IL, et al. Ostomy and pregnancy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:912.

103. Olsen KO, Joelsson M, Laurberg S, et al. Fertility after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in women with ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:493.

104. Lepisto A, Sarna S, Tiitinen A, et al. Female fetility and childbirth after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 2007;94:478.

105. Olsen KO, Juul S, Bulow S, et al. Female fecundity before and after operations for familial adenomatous polyposis. Br J Surg. 2003;90:227.

106. Yu CS, Pemberton JH, Larson D. Ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in patients with IC: Long-term results. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1487.

107. Dayton MT, Larsen KR, Christiansen DD. Similar functional results and complications after ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in patients with indeterminate vs ulcerative colitis. Arch Surg. 2002;137(6):690.

108. Selvasekar CR, Cima RR, Larson DW, et al. Effect of infliximab on short-term complications in patients undergoing operation for chronic ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:956.

109. Mor IJ, Vogel JD, Moreira AL, et al. Infliximab in ulcerative colitis is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1202.

110. Aylett SO. Three hundred cases of diffuse chronic ulcerative colitis treated by total colectomy and ileo-rectal anastomosis. Br Med J. 1966;1:1001.

111. Grundfest SF, Fazio V, Weiss RA, et al. The risk of cancer following colectomy and IRA for extensive mucosal chronic ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 1981;193:9.

112. Watts JM, Hughes SR. Chronic ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: Results after colectomy and IRA. Br J Surg. 1977;64:77.

113. Adson MA, Cooperman AM, Farrow GM. Ileorectostomy for ulcerative disease of the colon. Arch Surg. 1972;104:424.

114. Johnson WR, McDermott FT, Hughes ESR, et al. The risk of rectal carcinoma following colectomy in chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:44.

115. Pastore RL, Wolff BG, Hodge D. Total abdominal colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis for inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1455.

116. Leijonmarck CE, Löfberg R, Ost A, et al. Long-term results of ileorectal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis in Stockholm County. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:195.

117. Baker WNW, Glass RE, Ritchie JK, et al. Cancer of the rectum following colectomy and IRA for chronic ulcerative colitis. Br J Surg. 1978;65:862.

118. Wexner SD, Johansen OB, Nogueras JJ, et al. Laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy. A prospective trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:651.

119. Liu CD, Rolandelli R, Ashley S, et al. Laparoscopic surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. Am Surg. 1995;61:1054.

120. Thibault C, Paulin EC. Total laparoscopic proctocolectomy and laparoscopy assisted proctocolectomy for inflammatory bowel disease: Operative technique and preliminary report. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1995;5:472.

121. Hasegawa H, Watanabe M, Baba H, et al. Laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy for patients with ulcerative colitis. J Laparoendoscop Adv Surg Tech. 2002;12:403.

122. Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Piotrowicz K, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open ileal pouch anal anastomosis: Functional outcome in a case-match series. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1845.

123. Larson DW, Cima RR, Dozois EJ, et al. Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileal-pouch–anal anastomosis: A single institutional case-matched experience. Ann Surg. 2006;243:667-72.

124. Benavente-Chenhalls L, Mathis KL, Dozois EJ, et al. Laparoscopic ileal pouch–anal anastomosis in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: A case-matched study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:549.