Chapter 47 Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Other Interstitial Lung Diseases

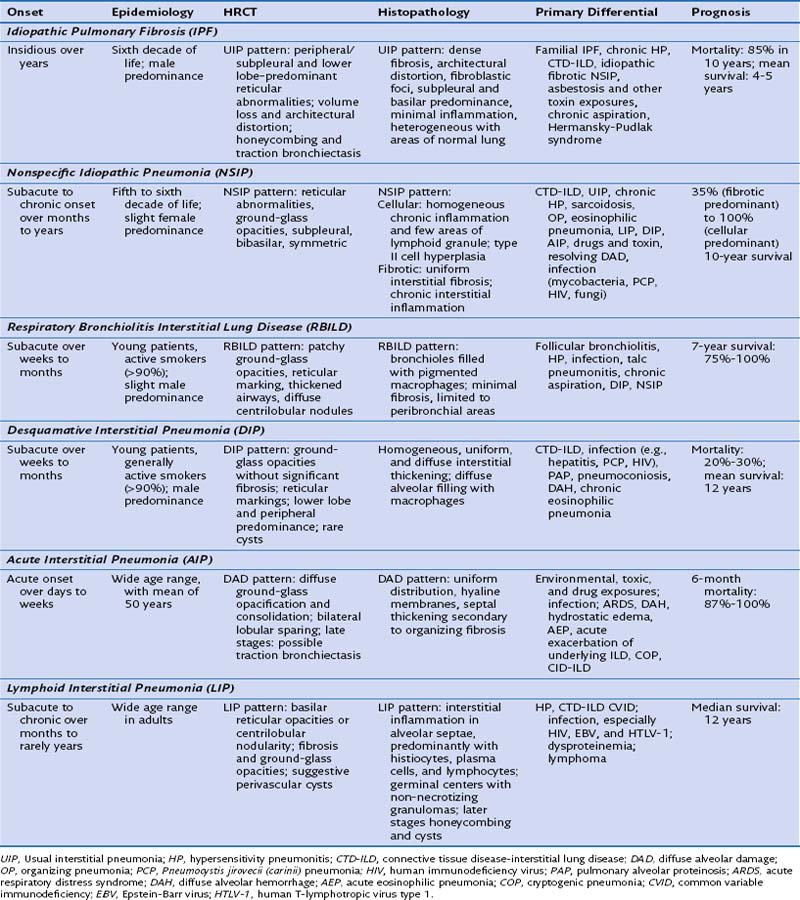

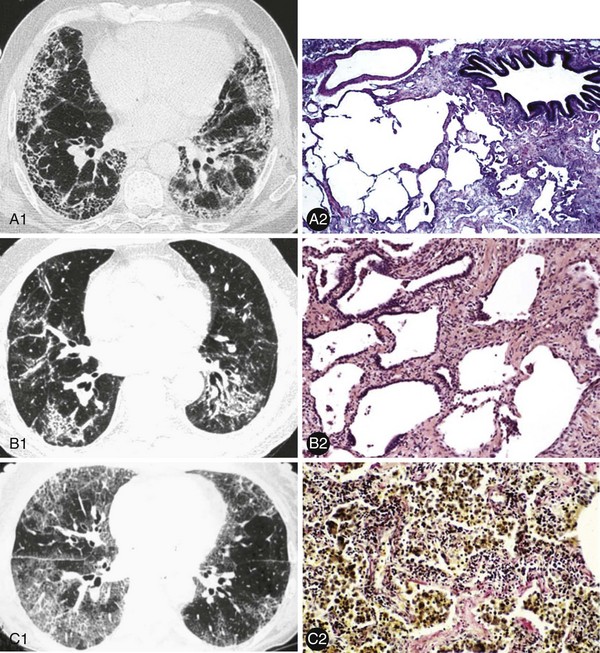

These ILDs differ based on epidemiology, onset of disease, chest imaging findings, histopathology, and most importantly, prognosis and response to treatment. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia presents and is treated similarly to noncryptogenic presentations of organizing pneumonia, as discussed in Chapter 50. The remaining idiopathic ILDs are discussed in this chapter. Table 47-1 compares various characteristics and Figure 47-1 shows some distinct radiologic and histologic patterns of these idiopathic ILDs.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

1. Extensive fibrosis and architectural distortion, characterized by significant myofibroblasts and fibroblasts and dense collagen in the interstitium. This may be with or without honeycombing.

2. Heterogeneous involvement of the lung with areas of diseased lung, mostly in the subpleural/basilar regions, intermixed with areas of normal lung.

1. Subpleural/basal predominance

2. Honeycombing with or without traction bronchiectasis

1. The clinical context is that of an idiopathic ILD; other potential causes or associations, including infection, drug or environmental exposures, and systemic disorders (e.g., CTDs), have been excluded.

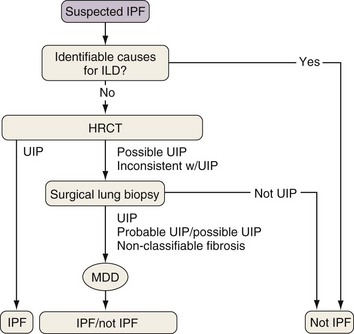

Because the diagnosis of IPF requires combining clinical, radiologic, and often pathologic information, multidisciplinary discussions with chest imagers and pathologists are strongly recommended, especially since a definitive diagnosis cannot be made based on radiologic and histologic findings alone. Figure 47-2 outlines an algorithm for the diagnosis of IPF.

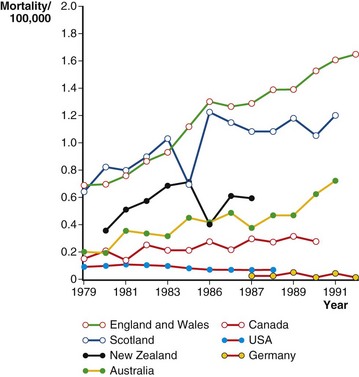

A study quantified the mortality rate associated with IPF in 2003 in the United States as 61.2 deaths per 1 million in men and 54.5 per 1 million in women, with 60% of deaths attributed to progressive lung disease. Increased rates are seen in older patients and in the winter months. Figure 47-3 compares mortality rates (per 100,000 population) from various countries. Although the median survival of symptomatic patients is generally accepted as 3 to 5 years, the survival of individual patients varies widely.

Figure 47-3 Mortality estimates for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in seven countries (1979–1991).

(Modified from Coultas DB et al: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 150:967–972, 1994.)

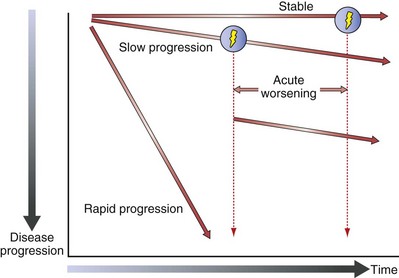

Figure 47-4 shows the natural history of IPF. Relatively stable lung function and slow (most common) or rapid disease progression can all occur. A patient’s course is unpredictable, and risk factors for decompensation are poorly understood. No clear consensus exists on a valid staging system for IPF. However, the specific characteristics used at diagnosis to identity patients with risk factors for early mortality include severity of dyspnea, lower forced vital capacity (FVC) or diffusion capacity (DLCO), significant desaturation on 6-minute walking distance (6MWD) testing, and the extent of fibrosis on HRCT. Other suggested risk factors include a shorter 6MWD, presence of significant emphysema, and pulmonary hypertension. Important longitudinal factors associated with an increased risk of early mortality in IPF patients are worsening dyspnea, decline in FVC, decline in DLCO, and increasing extent of disease on HRCT.

Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonia

Treatment and Prognosis

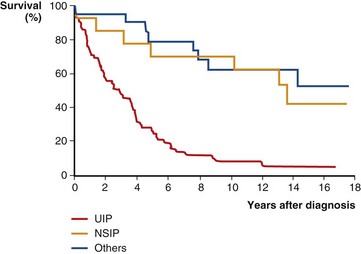

Prospective, controlled therapeutic trials are lacking in the treatment of patients with NSIP, and expert opinion provides the basis for most recommended regimens. Corticosteroids are typically initiated in these patients, with an anticipated transition to steroid-sparing agents such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclophosphamide. The prognosis of NSIP is variable, with a minority of patients with progressively fatal disease and others with nearly complete recovery. Patients with a predominantly fibrotic NSIP have a worse prognosis than those with predominantly cellular NSIP. The majority of patients will have relatively stable disease or some mild improvement with therapy. Overall, mortality is better than with UIP. Figure 47-5 compares the survival curves of patients with NSIP, UIP, and other idiopathic ILD.

2002 American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304. erratum, 166:426, 2002

Bjoraker JA, Ryu JH, Edwin MK, et al. Prognostic significance of histopathologic subsets in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:199–203.

Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:967–972.

Demedts M, Wells AU, Antó JM, et al. Interstitial lung diseases: an epidemiological overview. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2001;32:2–16.

Frankel SK, Schwarz MI. Update in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15:463–469.

Gal AA, Staton GWJr. Current concepts in the classification of interstitial lung disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;123:S67–S81.

Kim DS, Collard HR, King TEJr. Classification and natural history of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:285–292.

Leslie KO. Historical perspective: a pathologic approach to the classification of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Chest. 2005;128(5 Suppl 1):513–519.

Ley B, Collard HR, King TEJr. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:431–440.

Lynch DA, Travis WD, Müller NL, et al. Idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: CT features. Radiology. 2005;236:10–21.

Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824.

Travis WD, Hunninghake G, King TEJr, et al. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: report of an American Thoracic Society project. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:1338–1347.

Vassallo R, Ryu JH. Tobacco smoke–related diffuse lung diseases. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;29:643–650.