Iatrogenic Vaginal Constriction

Introduction

Vaginal stricture may occur secondary to inflammatory conditions of the vagina, vaginal surgery, episiotomy repair, or radiotherapy. The surgical approach to the stenosis depends on its anatomic location, underlying cause, and severity. For introital or vaginal stenosis, the procedure can treat both upper and lower vaginal strictures or can correct lower vaginal strictures specifically. Operations that correct upper and lower vaginal strictures include incision of the vaginal constriction ring or ridge, vaginal advancement, Z-plasty, free skin graft, perineal flaps, and abdominal flaps. Restenosis risk is high after these interventions; therefore, postoperative care must include rigid dilation that is initiated immediately in the postoperative period.

Incisions

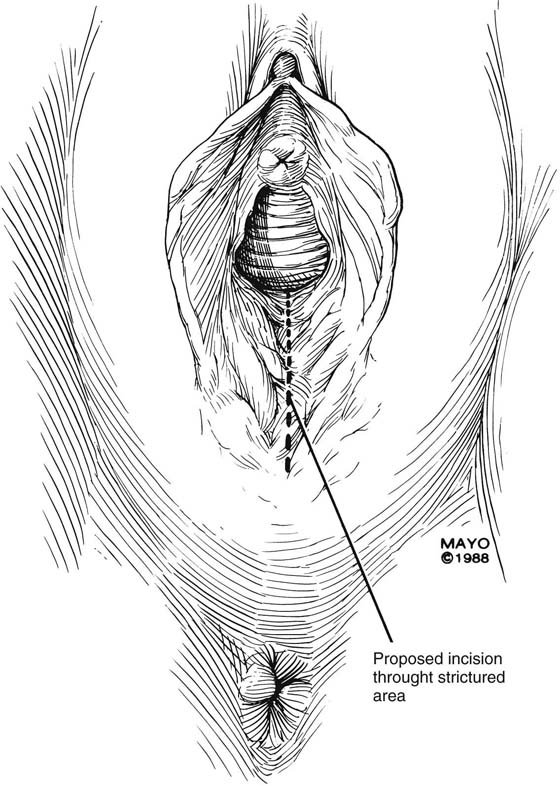

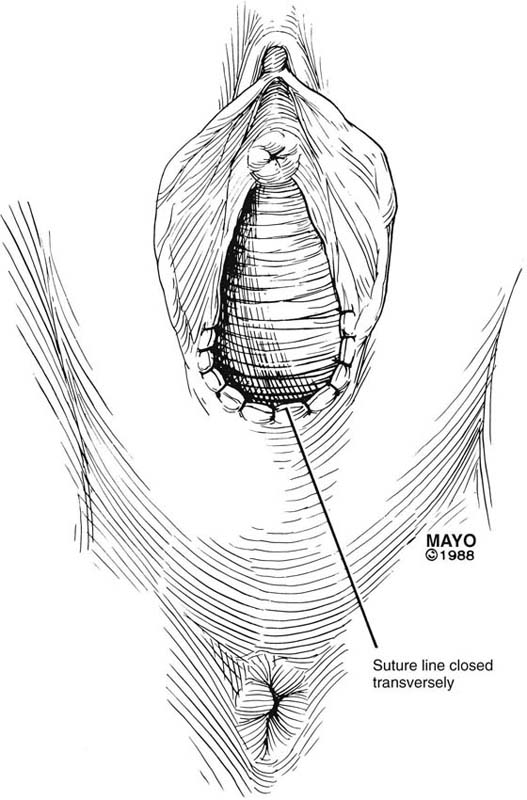

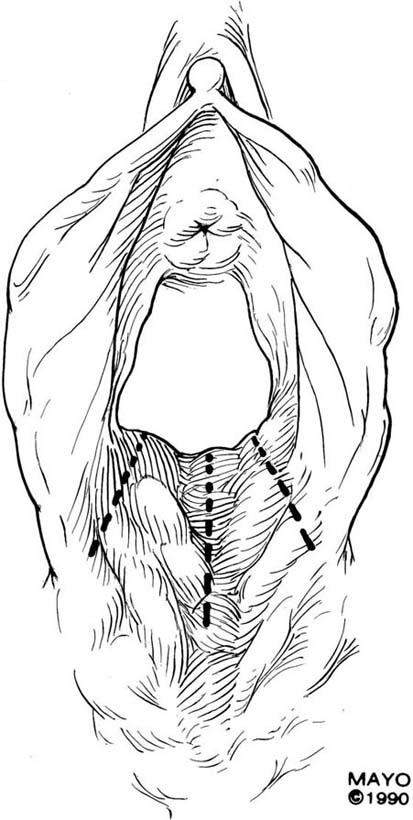

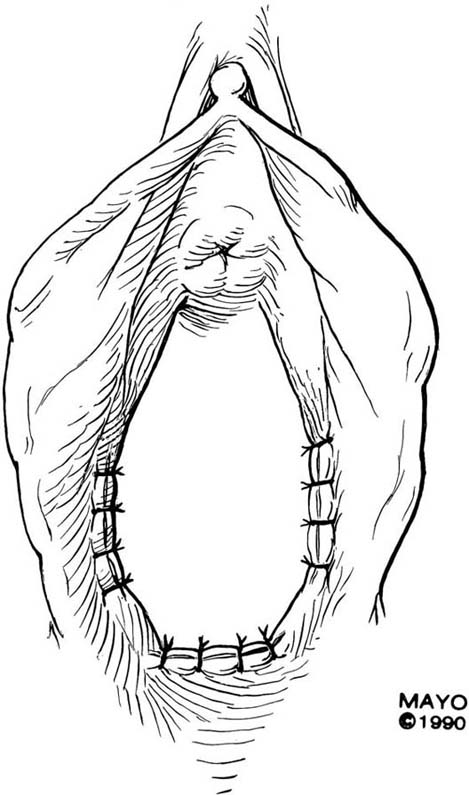

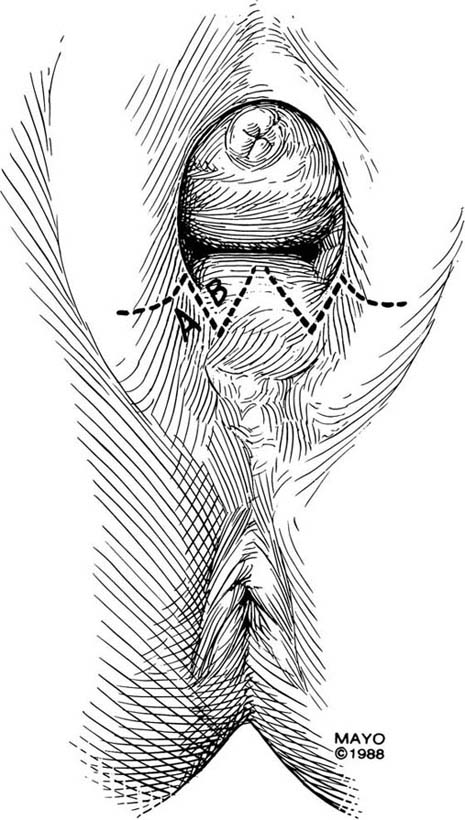

The simplest approach to a vaginal constriction is a midline incision of the contracting scar or ridge. The midline incision is made, and the vaginal mucosa is mobilized from the underlying scar (Fig. 62–1). Excessive scar tissue may be excised completely to increase the vaginal or introital diameter. When hemostasis is achieved, the wound may be left to heal by secondary intention, or the vaginal tissue may be undermined and advanced and the incision closed transversely in a tension-free manner (Fig. 62–2). When a single midline incision with transverse closure is inadequate, numerous vertical incisions may be made (Fig. 62–3). Separate vertical incisions are closed transversely—after mobilization of surrounding vaginal tissues—to obtain sufficient introital or vaginal diameter (Fig. 62–4).

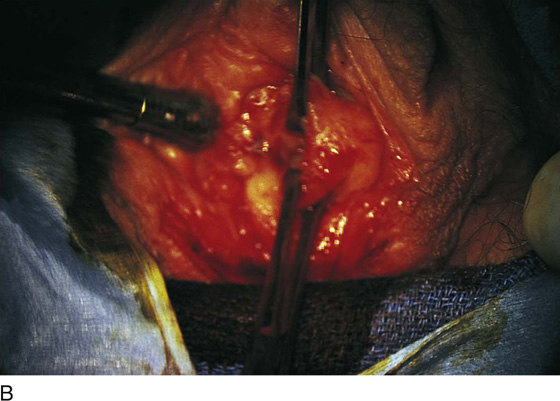

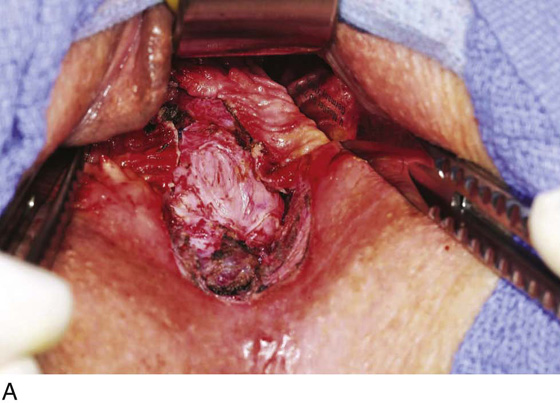

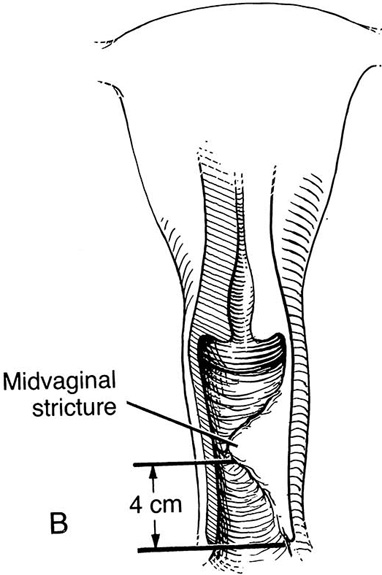

Figure 62–5A shows a midvaginal constriction ring after an overzealous anterior and posterior colporrhaphy. The stenotic site was initially enlarged with the use of Hegar dilators passed from the lower vaginal segment into the upper segment. When the vagina was dilated to at least 10 mm, bilateral longitudinal incisions were made in the lateral aspect of the stenotic site and were taken along the vaginal axis (Fig. 62–5B). The tight fibrous band was completely excised, and the dissection continued until loose connective tissue was encountered in the ischiorectal space (Fig. 62–5C). Some surgeons prefer to leave the space open; others prefer to close it transversely and perpendicular to the original incision, using interrupted, 3-0 absorbable sutures.

Z-Plasty

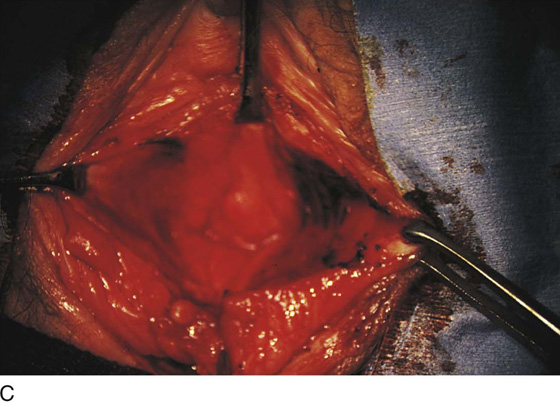

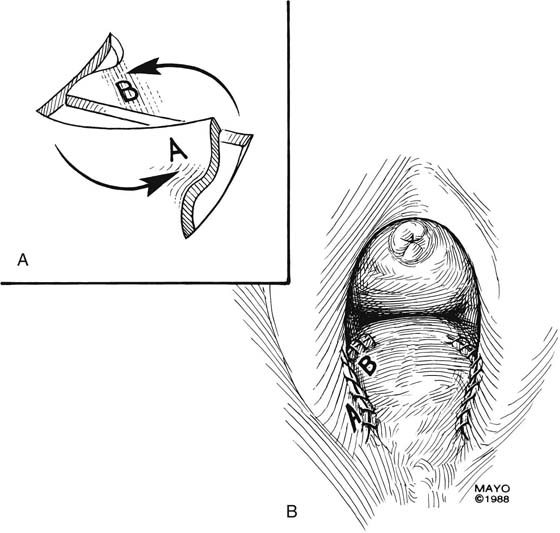

The Z-plasty technique involves transplantation of two interdigitating triangular flaps. The orientation of the Z may be vertical or transverse, depending on the stricture. The degree of stenosis determines the incision length of the flap arms and the flap angles. Typically, the flaps are 2 cm long and at 60° angles. Additional diameter is gained by increasing the angle. The midpoint, or the site of the most severe contracture, is identified, and a transverse incision is made (this incision becomes the common limb of the Z-plasty). The upper arm of the Z is extended into the vagina; the lower arm is extended toward the perineum (Fig. 62–6). Scar tissue, if present, may be excised, and the transposed flaps are reapproximated with interrupted, 3-0 or 4-0 absorbable sutures (Fig. 62–7).

Introital stricture may be amenable to a transverse Z-plasty. This technique results in the absence of a midline suture line. Duplication of the flaps at the 4- and 8-o’clock positions of the introitus results in an increase in introital diameter (Fig. 62–8). Care must be taken to approximate the apices of the incisions and thereby to gain maximum transverse diameter. “Dog ears” should be trimmed and absorbable sutures used to produce a smooth approximation of tissues (Fig. 62–9).

FIGURE 62–1 A midline incision is made and the vaginal mucosa is widely mobilized, excising the underlying scar tissue as needed. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–2 To increase vaginal diameter, the initial vertical incision is closed in a transverse manner. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–3 In cases of broader areas of scarring and stenosis, numerous vertical incisions may be used. The surrounding tissues are mobilized, and excessive scar tissue is excised. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–4 Numerous vertical incisions may be converted to multiple transverse closures, thereby increasing the diameter at the area of stricture. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–5 A. Midvaginal constriction ring that occurred after an overzealous anterior and posterior repair. The image shows the Hegar dilator in the small opening. B. Because the vagina was sufficient above this ring, bilateral relaxing incisions were performed to reopen the vagina. Allis clamps were used to grasp the ring in preparation for the incision. An incision was made at both 4 and 7 o’clock. C. The incisions were continued until the band was completely incised and loose areolar tissue was encountered. The incision was left open to heal by secondary intention.

FIGURE 62–6 The midpoint of the scar is identified, and a transverse incision made. This incision site becomes the common arm of the Z-plasty. The upper arm of the Z is extended into the upper vagina; the lower arm of the Z is extended toward the perineum. The area of stricture determines the length and angle of the incisions. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–7 A. After mobilization, the scar tissue is excised and the flaps interposed. B. The transposed flaps are reapproximated in a tension-free manner with interrupted sutures. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–8 The Z-plasty may be made on either side of the introital opening, which results in a lateral incision closure and the absence of an incision in the midline. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–9 A. After the incisions are made and the tissues mobilized, the subcutaneous tissues are separately approximated. B. The overlying mucosa is closed with interrupted, 4-0 delayed absorbable suture. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

Free Skin Grafts

Full-thickness skin grafts may be used for repair of vaginal stenosis or vaginal shortening. These grafts, in contrast to split-thickness grafts, are used because they cause less postoperative contracture. A full-thickness graft composed of dermis and epidermis (with all fat removed) can be harvested from any site on the body. Relaxing incisions can be made in the vagina through the area of stenosis, and the graft is sewn into place with fine absorbable sutures. The vagina should be packed with moistened gauze for at least 24 hours after the procedure.

Xenografts

Xenografts are acellular extracts of collagen—with or without additional extracellular matrix components—that are harvested from nonhuman sources. They differ in the source species (bovine or porcine), in the site of harvest (pericardium, dermis, or small intestine submucosa), and by whether chemical cross-linking is used in processing the material.

Xenograft materials include Surgisis (Cook Biotech Inc, West Lafayette, Indiana), an extracellular matrix material derived from the submucosa of the porcine small intestine. It contains structural and functional proteins arranged in a tissue-specific orientation for direct healing and tissue remodeling. Surgisis has been used as an alternative to split-thickness skin grafting in human patients with full-thickness chronic leg ulcers and granulating open dermal wounds. It is available in various sizes and thicknesses.

We have used four-layer Surgisis successfully to bridge gaps in vaginal epithelium or perineal skin in cases where approximating the tissue would cause narrowing or foreshortening. In this use, the surrounding vaginal epithelium is undermined, and the graft is laid flat beneath the epithelium and is secured in place with sutures (Fig. 62–10). The graft is generally well accepted by the body and remodels to become nearly indistinguishable from surrounding tissue. It is essentially used in lieu of a skin graft. Porcine small intestine submucosa is recommended over porcine dermis when used to replace or bridge epithelial defects.

Perineal Flaps

Lateral strictures near the introitus or farther up the vaginal canal may result in dyspareunia or in a functionally shortened vagina. In addition, inflammatory conditions (e.g., lichen planus, Behçet disease) may cause vaginal obliteration. Perineal flaps provide a potentially large and vascular tissue source to aid in management of various strictures and obliterative conditions.

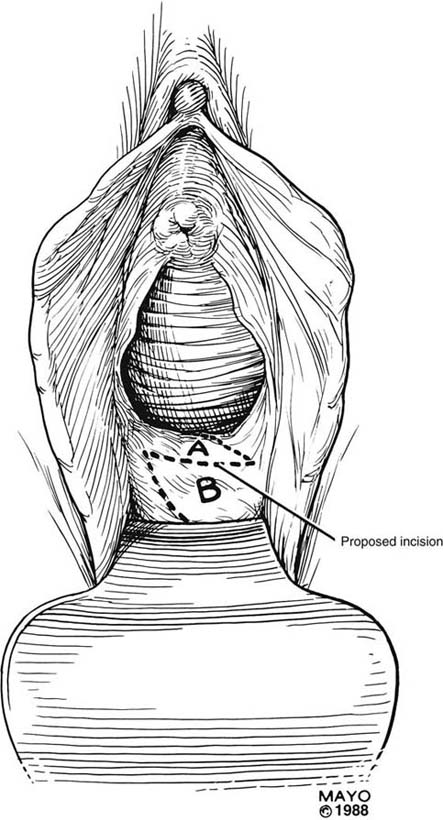

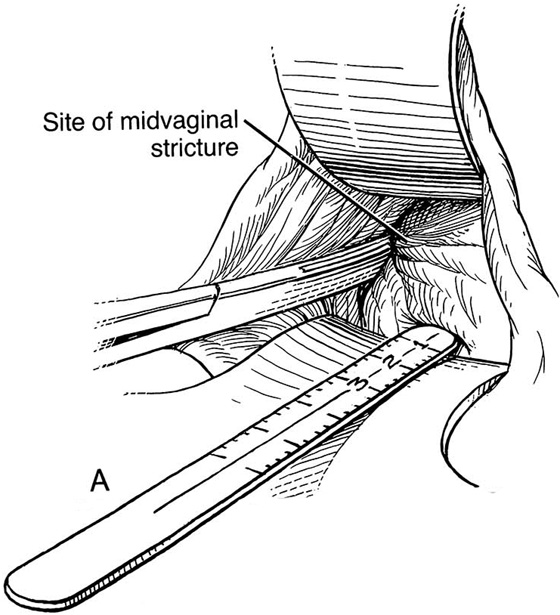

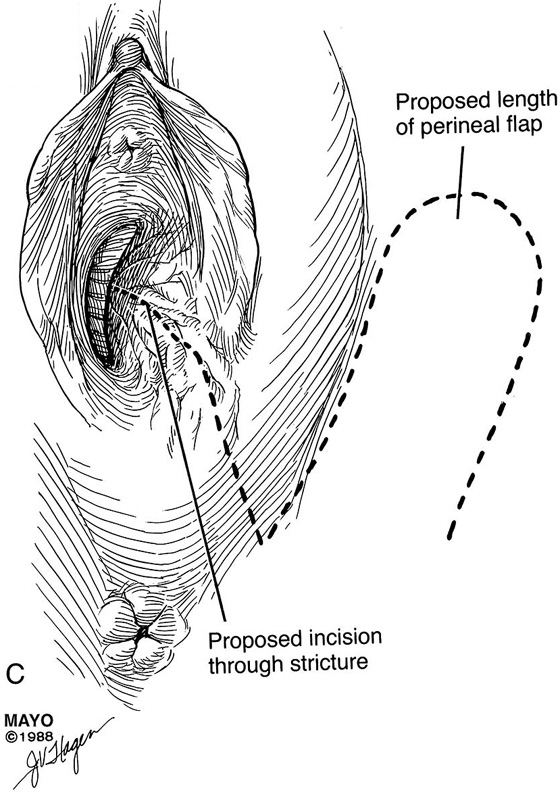

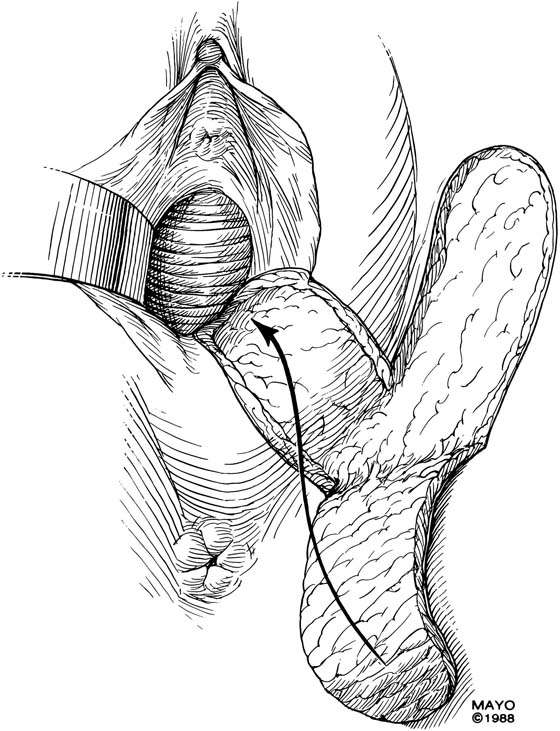

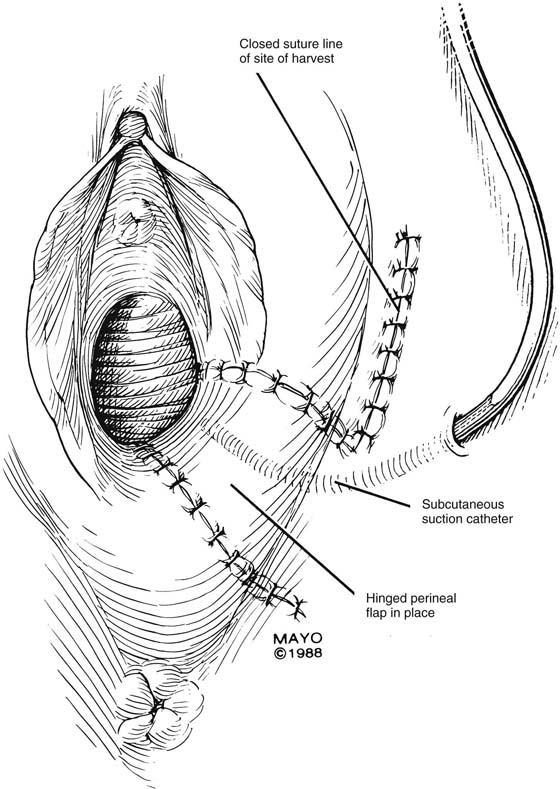

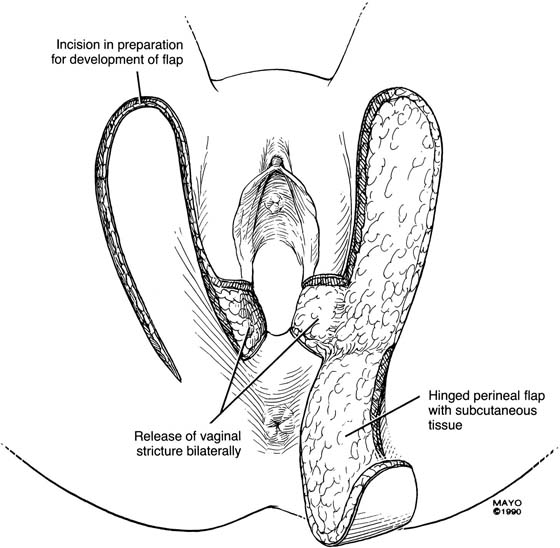

An incision is made throughout the entire longitudinal extent of the introital and vaginal scar (Fig. 62–11). The area is undermined to open the contracture completely. After measurements are taken to calculate the desired flap length, a hinged perineal flap is created immediately lateral to the labium majus on the side of the contracture (Fig. 62–12). The blood supply (in the flap base) generally supports a flap length several times the width of the flap base. A portion of subcutaneous fat is preserved on the flap to maintain a blood supply and results in a soft pad at the previous contracture site. The flap is rotated into the vaginal space and is secured in place with fine, absorbable, interrupted sutures after hemostasis is obtained. A suction catheter may be placed beneath the flap and generally is removed in 24 to 48 hours (Fig. 62–13).

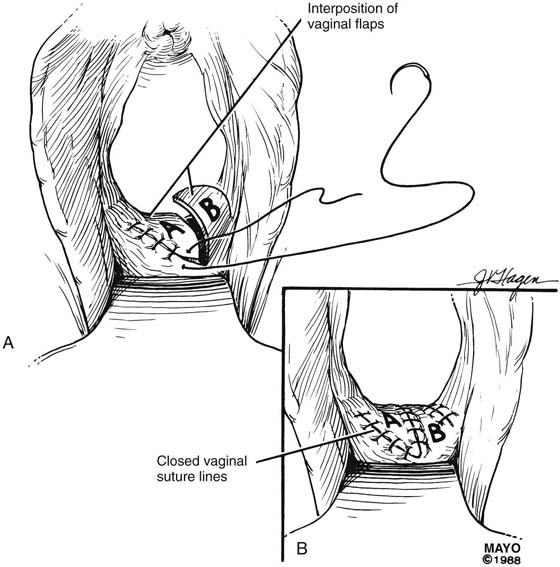

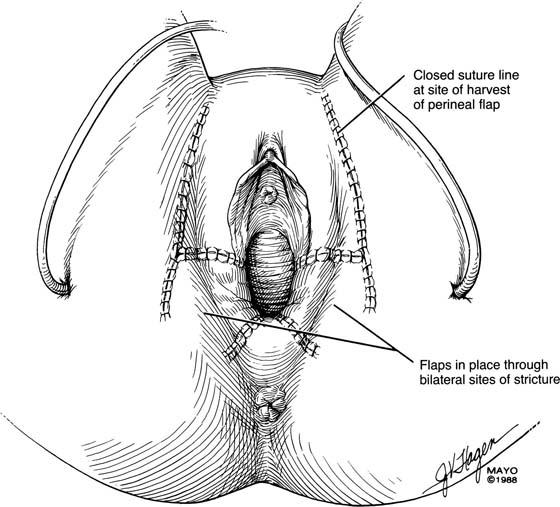

Occasionally, bilateral flaps (Fig. 62–14) are required to adequately address a large stricture or a complete vaginal obliteration. The resultant vagina and introitus should have adequate diameter and depth and should be completely free of any contracting bands or scars (Fig. 62–15).

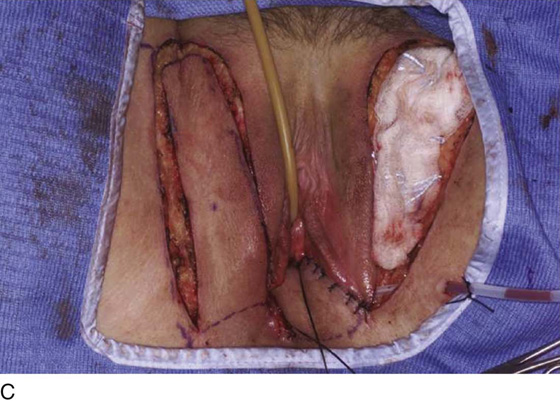

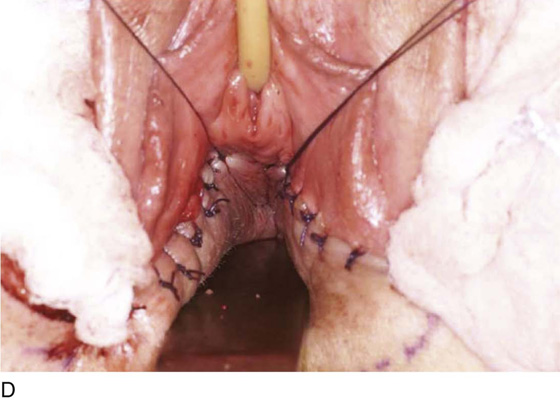

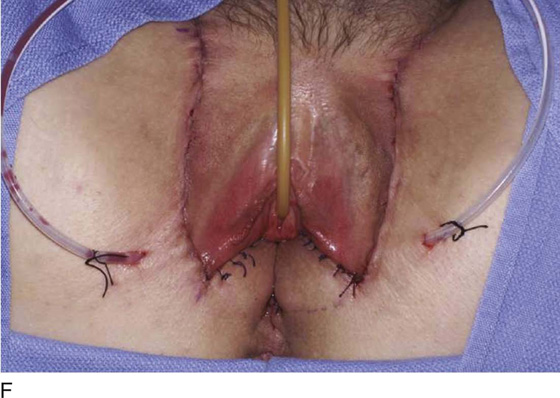

Figure 62–16 shows an example of vaginal obliteration from Behçet disease. Several prior attempts at repair were unsuccessful. After meticulous vaginal dissection and the placement of relaxing incisions at 4 and 8 o’clock, measurements were taken, and the left perineal flap was mobilized (Fig. 62–16A) and rotated into the dissected area (Fig. 62–16B). Interrupted sutures secured the flap in place after placement of a drain. Measurements were taken on the right side, and the right perineal flap was mobilized (Fig. 62–16C). Again, interrupted sutures were used to secure the flap after placement of a drain beneath the mobilized flap (Fig. 62–16D). Deaver and right-angle Heaney retractors were used to gain exposure to the vaginal apex and secure the proximal interrupted sutures (Fig. 62–16E). The skin surrounding the groin harvest sites was undermined to aid in a tension-free closure. (Bringing the patient’s legs down from the lithotomy position may be helpful for this part of the procedure.) The groin incisions were then closed in two layers: an interrupted subcutaneous layer to ease tension on the skin, and a subcuticular layer to close the skin (Fig. 62–16F). An ice pack was applied to help limit swelling, and a Foley catheter was left in place for several days to assist in bladder drainage.

Abdominal Flaps

When other, more traditional options have failed or circumstances dictate that a new tissue source must be used, abdominal flaps provide an alternative. Abdominal flaps are often used in other surgical procedures, such as breast reconstruction, and they may be applicable in gynecologic reconstruction as well. Vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps and transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flaps may be used for vaginal reconstruction in patients with vaginal stricture who have had previously unsuccessful procedures, and for vaginal reconstruction in patients with gynecologic malignancy.

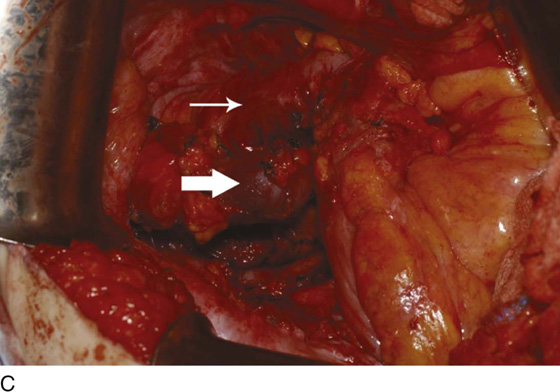

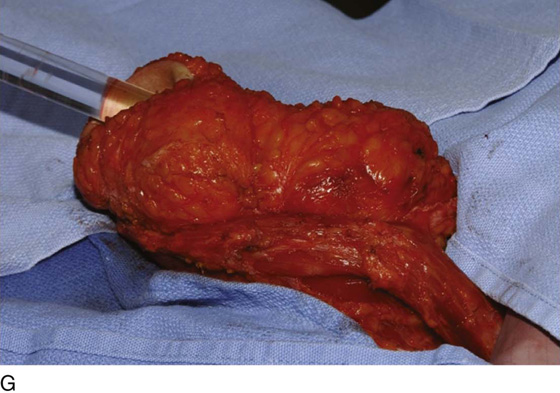

Figure 62–17 illustrates the use of a vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap in a patient who underwent radical resection of a rhabdomyosarcoma of the perineum at a very young age. Several subsequent operations failed to create a functional vagina. Figure 62–17A shows a multioperated perineum with a sigmoid neovagina, in which stricture developed over time (bilateral labial flaps and bilateral Singapore flaps had previously failed). In the planning of surgical incisions, preoperative markings were made (Fig. 62–17B). The sigmoid neovagina was isolated and mobilized from above (Fig. 62–17C). The mobilized sigmoid neovagina was everted (Fig. 62–17D) and excised at the perineum (Fig. 62–17E). The left rectus abdominis muscle, overlying skin, and adipose tissue (i.e., the vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap) were isolated (Fig. 62–17F), sacrificing the superior blood supply while preserving the inferior blood supply (i.e., the inferior epigastric artery). The flap was then configured in a helical manner with interrupted and continuous, delayed absorbable sutures (Fig. 62–17G) and was rotated into the pelvis, where it was secured to the perineum (Fig. 62–17H) with interrupted, delayed absorbable sutures. (The bulk of the neovagina may make this step a challenging part of the reconstruction.) The fascial defect was then approximated directly or with the use of a graft, and the overlying skin was closed primarily (Fig. 62–17I).

The advantages of abdominal flaps for vaginal reconstruction include the availability of a large, well-vascularized, and generally undisturbed tissue source that usually does not require dilation postoperatively. Disadvantages include the potential for partial graft skin slough, which may require further surgical intervention and grafting. In addition, these tissue flaps are often bulky (depending on the patient’s body habitus) and may be difficult to interpose between the bladder and the rectum and to attach to the perineum.

FIGURE 62–10 Operative photos show the use of four-layer extracellular matrix material (Surgisis; Cook Biotech Inc, West Lafayette, Indiana) in replacing epithelium after vaginal and perineal reconstruction. A. A large defect along the distal posterior vaginal wall and perineal body after excision of vaginal mesh secondary to dyspareunia. Closing the wound primarily would cause introital narrowing. B. The graft sutured into place. C. A painful vertical scar at the vaginal apex excised and the defect bridged with the graft. D. The vaginal apex 6 weeks later. E. Perineal scarring after an episiotomy, causing dyspareunia. F. Large perineal defect after excision of the scarred tissue. G. Graft sutured into place to bridge the defect. H. The perineum 6 weeks after surgery.

FIGURE 62–11 A. A ruler and curved tissue forceps used to define the area of stricture and to plan the size of graft needed for harvest. B. A narrowed midvaginal contracture in a longitudinal view, emphasizing a thick scar with a narrow passage connecting the upper and lower vagina. C. The proposed incision and perineal flap. An incision is made in the introitus and is extended through the constriction. The scar is incised and completely excised, and the surrounding tissues are adequately mobilized in preparation for a perineal flap. The region and extent of contracture determine the size of the perineal graft. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–12 After the contracture has been excised and the surrounding tissues mobilized, measurements are taken to determine the size of graft required. A hinged perineal graft is then created immediately lateral to the labium majus on the side of the contracture. The blood supply in the hinge region must be preserved. Making the distal end of the flap round rather than pointed is advised, to reduce the risk of slough of the distal aspect of the graft. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–13 A suction catheter is placed in the wound bed and is extended laterally. The flap is rotated into the defect and is secured to the adjoining tissue with interrupted sutures. The initial sutures secure the flap near the vaginal apex; subsequent sutures are placed toward the introitus, with care taken to avoid asymmetry. The tissue lateral to the labium majus is circumferentially mobilized to allow the incision to be closed in a tension-free manner. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–14 When a circumferential constriction or vaginal obliteration is encountered, bilateral perineal flaps may be required. The principles described in Figure 59–10 and Figure 59–11 and Figure 59–12 apply to this type of repair as well. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–15 Bilateral perineal flaps should yield a functional vagina. Meticulous hemostasis is required. Harvesting a graft that is approximately 1 cm longer than the vaginal incision is advised, to ensure adequate graft length and a tension-free closure. (Adapted from Lee RA: Atlas of Gynecologic Surgery. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, ©1992. Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.)

FIGURE 62–16 Bilateral perineal flaps in a patient with vaginal obliteration from Behçet disease. The patient previously underwent two vaginal dissections that quickly resulted in restenosis of the vagina. Adequate control of her underlying disease process, the desire for a functional vagina, and the failure of previous vaginal dissections led to the advice to use bilateral perineal flaps for reconstruction. A. The vaginal dissection has been completed, and measurements have been taken to determine the size of graft needed. The left perineal flap was thus mobilized. A broad base at the hinge preserved the blood supply, and rounding of the distal tip was performed. B. The left perineal flap was rotated into the defect and was secured to surrounding tissue with interrupted sutures. C. When the left perineal flap was secured, vaginal dissection was repeated on the right side, measurements were taken, and the right perineal flap was mobilized. D. Interrupted sutures, starting at the apex and working toward the introitus, were placed to secure the grafts in a symmetrical and tension-free manner. E. After the flaps were secured in place, the tissue surrounding the incisions lateral to the labia majora was mobilized. Often, the lateral aspect of the incision can be mobilized to a greater degree than the medial aspect, to avoid a tethering effect on the remaining labial and periclitoral tissues. F. An initial layer of interrupted sutures was placed to reapproximate the subcutaneous tissues in the lateral incisions. This placement reduced tension on the overlying skin closure. The skin was then reapproximated with a running subcuticular, delayed absorbable suture. A Foley catheter was left in place to drain the bladder, and an ice pack was applied to limit edema. Tissue edema in the perineal flaps was not uncommon, and the grafts were monitored for evidence of vascular compromise.

FIGURE 62–17 Use of a vertical rectus abdominis myocutaneous (VRAM) flap for vaginal reconstruction in a patient who at a very young age underwent radical resection of a rhabdomyosarcoma of the perineum, followed by pelvic irradiation. Vaginal stricture and hematocolpos developed. She eventually underwent hysterectomy, bilateral perineal flap, bilateral Singapore flap construction, and, finally, construction of a sigmoid neovagina, in which stenosis ultimately developed. A. The perineal area showed extensive scarring from previous operations and pelvic irradiation. The mucosa of the sigmoid neovagina had erythema from chronic irritation. B. The left rectus abdominis muscle was marked for future harvest. C. The sigmoid neovagina with a Lucite dilator in place (thick arrow) underwent stenosis and was mobilized from the left pelvic sidewall and adjacent rectum (thin arrow). D. After mobilization abdominally, the sigmoid neovagina was everted through the vagina and excised. E. With sharp dissection and cautery, the sigmoid neovagina was dissected free from the overlying bladder and urethra and underlying rectum. A preoperative left external ureteral stent was placed to aid the identification and dissection of the left ureter. F. The left VRAM flap was isolated, sacrificing the superior blood supply. G. The VRAM flap was rolled in a helical fashion to create a neovagina, and the skin edges were secured with interrupted and continuous delayed absorbable sutures. H. The VRAM-flap neovagina was then rotated into the pelvis and secured to the perineum with interrupted sutures. I. After the fascial edges were reapproximated, the skin was closed, leaving a long, vertical midline scar.

Mickey M. Karram

Mickey M. Karram