Hysterectomy for Benign and Malignant Conditions

Introduction

Hysterectomy may be performed for both benign and malignant conditions of the uterus. The surgical approach to hysterectomy is determined by the pathology at hand as well as operator experience. Surgical approaches may include total abdominal hysterectomy, total laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy, robotic hysterectomy or total vaginal hysterectomy. This chapter focuses on the basic description of the total abdominal extrafascial hysterectomy. Oophorectomy is described in Chapter 52.

Surgical Anatomy

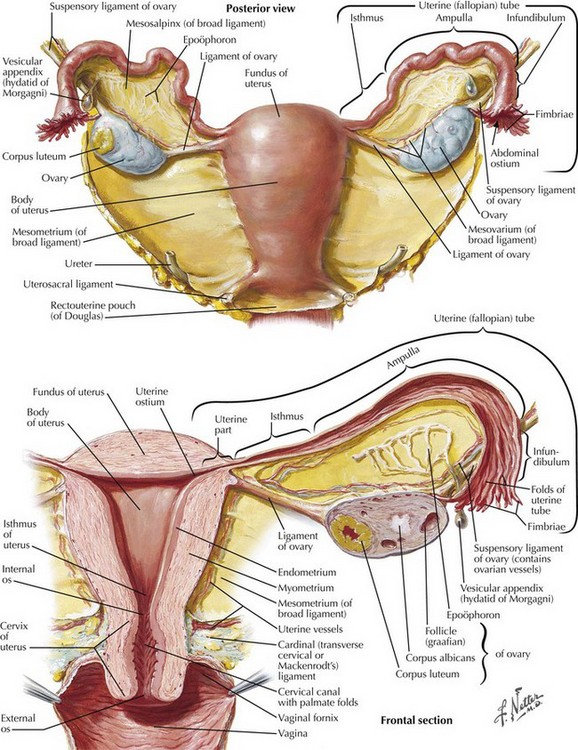

Cardinal and Uterosacral Ligaments

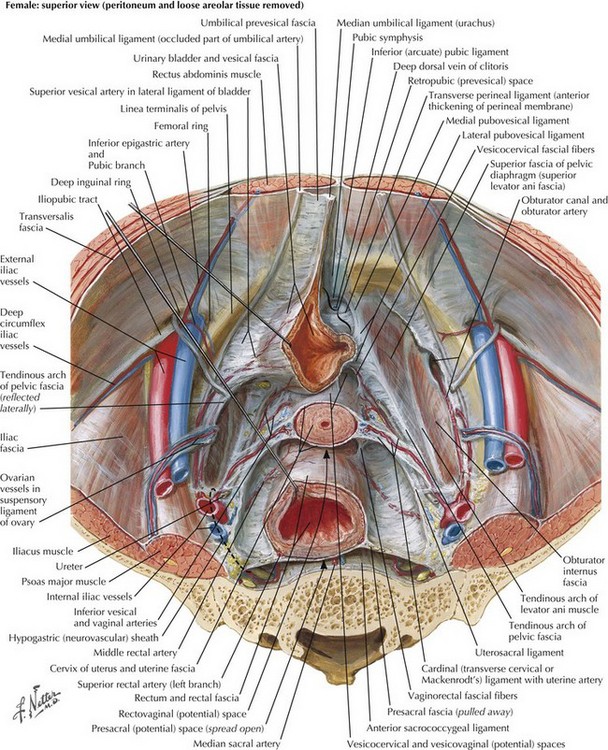

Excellent knowledge of both intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal anatomy is critical to perform a hysterectomy. Uterine support is provided by the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments (Fig. 51-1). The cardinal ligaments extend laterally from the level of the cervical-uterine junction and divide the pelvic cavity in potential spaces: the paravesical spaces divide the cavity anteriorly and the pararectal spaces divide it posteriorly. The uterosacral ligaments extend from the cardinal ligaments posteriorly toward the ischial spines and sacrum. Between the uterosacral ligaments lies the uppermost portion of the rectovaginal septum covered by peritoneum. This area can serve as the entry point into the retrouterine space.

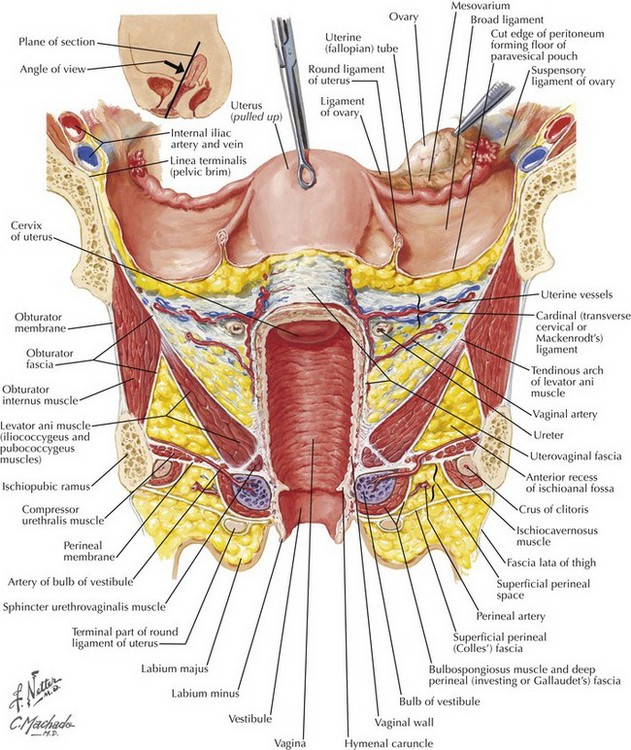

Round and Broad Ligaments

The broad ligament consists of an anteroposterior layer of peritoneum draped over the uterus and extends from the round ligament to the infundibulopelvic ligaments posteriorly (Fig. 51-2). The retroperitoneal space and structures can be accessed through the broad ligament, which contains areolar fat.

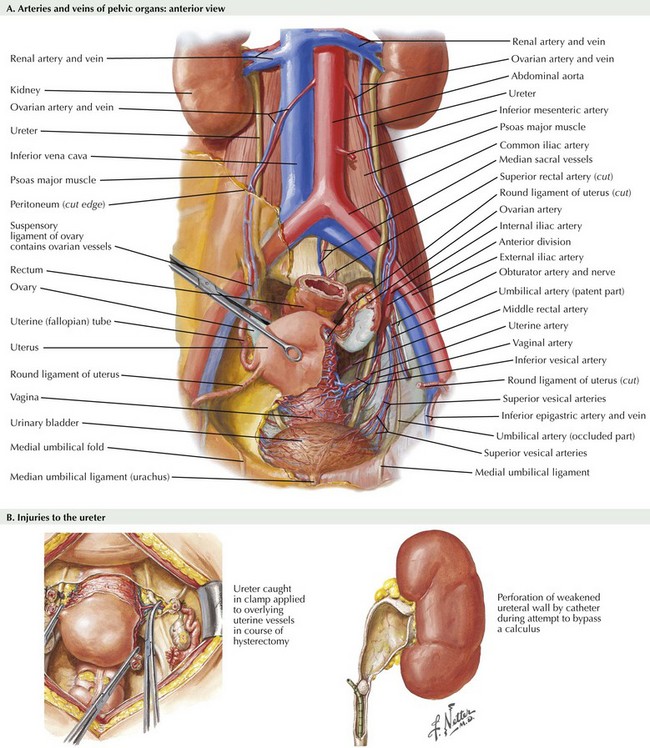

Vascular Landmarks and Ureteral Injury

Uterine blood supply is derived from the uterine artery, which originates in the anterior branch of the hypogastric (internal iliac) artery (Fig. 51-3, A). Additional branches and collateral vessels include the vaginal and cervical branches of the uterine artery. The uterine artery crosses the lower third of the ureter before the uterine entry point at the cervicouterine junction. The majority of pelvic surgery–related ureteral injuries occur at this location, and detailed knowledge of ureteral anatomy and the relationship to the uterus and uterine blood supply is necessary to avoid iatrogenic injury to the ureter (Fig. 51-3, B).

Hysterectomy

Surgical Approach

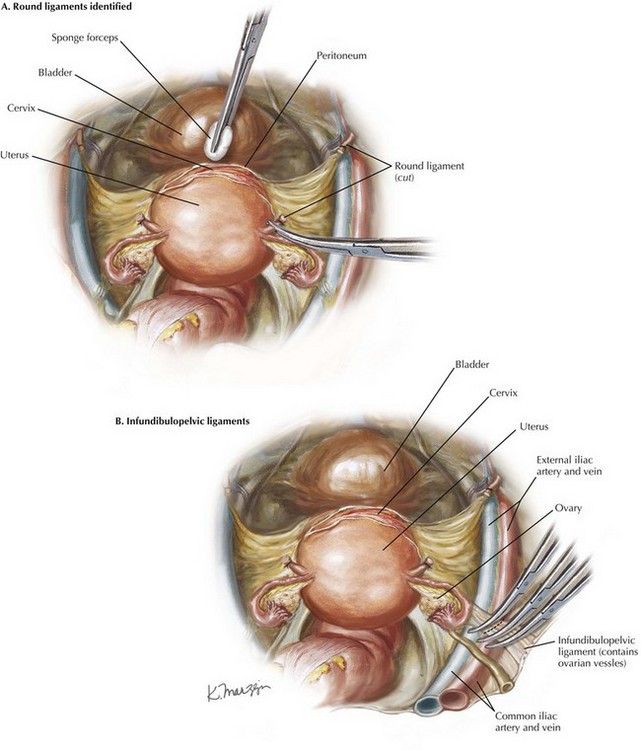

Kelley clamps are placed on the uterine cornua bilaterally, and gentle upward traction is used. The round ligaments are identified bilaterally and suture-ligated with 0 Vicryl (Fig. 51-4, A). These sutures are left long and tagged. The round ligaments are transected, and the retroperitoneal space is entered.

Abdominal Dissection

The posterior broad ligament is dissected parallel to the course of the infundibulopelvic ligaments bilaterally (Fig. 51-4, B). If significant dissection into the retroperitoneum is planned, this dissection may be continued along the white line of Toldt, with mobilization of the cecum and the sigmoid colon. Once this dissection is performed, the retroperitoneal space is now clearly visible through the layer of areolar fat. This tissue may be dissected with gentle blunt dissection, monopolar cautery, or gentle dissection with a suction tip.

The ureter will be identified coursing along the medial leaf of the broad ligament, below the infundibulopelvic ligaments. The pararectal space may be developed by gentle dissection between the hypogastric artery and ureter (Fig. 51-5). The author recommends awaiting ureteral peristalsis so as not to confuse the ureter with anterior division of the hypogastric artery.

Once these structures are clearly identified and the ureters identified and out of harm’s way, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may be performed (see Chapter 52).

Baggish, MS, Karram, MM. Atlas of pelvic anatomy and gynecologic surgery, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

Rock, JA, Jones, HW. TeLinde’s operative gynecology, 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Wheeless, CR, Parker, J. Atlas of pelvic surgery, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 1997.