Hypothermia

Definition

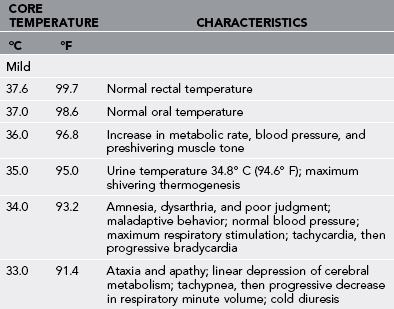

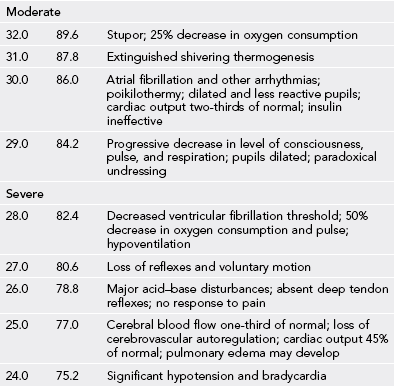

Accidental hypothermia is the unintentional decline of at least 2° C (3.6° F) from the normal human core temperature of 37.2° to 37.7° C (99° to 99.9° F) that occurs in the absence of any primary central nervous system causation. It is both a symptom and a clinical disease entity. Hypothermia occurs in mild, moderate, severe, or profound forms (Table 3-1) and can present as either a primary disorder resulting from environmental exposure or secondary to other causes, such as trauma, infection, or metabolic disease.

General Treatment

1. Consider rescuer scene safety factors, including unstable snow, ice, and rock fall.

2. Handle all patients suspected of having moderate or severe hypothermia carefully to avoid unnecessary jostling or sudden impact. Rough handling can cause ventricular fibrillation. Consider aeromedical evacuation.

3. The rescuer should stabilize injuries, protect the spine, splint fractures, and cover open wounds (Box 3-1).

4. Prevent further heat loss; insulate the patient from above and below (Box 3-2).

5. Anticipate an irritable myocardium, hypovolemia, and a large temperature gradient between the periphery and the core.

6. Anticipate problematic intravenous (IV) access, and carry intraosseous (IO) infusion systems, which are compatible with crystalloids, colloids, and medications.

7. Treat hypothermia before treating frostbite.

8. Reconsider the decision to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the field if there is evidence of lethal injury.

Disorders

Treatment

1. Gently remove all wet clothing, and replace it with dry clothing.

2. Insulate the patient with sleeping bags, cloth pads, bubble wrap, blankets, or other suitable material.

3. Always insulate the patient from the ground up. Use adequate insulation underneath the patient.

4. If the patient is capable of purposeful swallowing (will not aspirate), encourage drinking of warm and sweet drinks such as warm gelatin (Jell-O), reconstituted fruit beverages, juice, or decaffeinated tea or cocoa, because carbohydrates fuel shivering. Avoid heavily caffeinated drinks to prevent further diuresis.

5. If a mildly hypothermic patient is well hydrated and insulated from further cooling, he or she can often walk out to safety.

Moderate Hypothermia

Signs and Symptoms

1. Stupor progressing to unconsciousness

3. Atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias, bradycardia

5. Mild to moderate hypotension

6. Diminished respiratory rate and effort, bronchorrhea

8. Diminished neurologic reflexes and voluntary motion

9. Decreased ventricular fibrillation threshold

Treatment

If the patient is confused, stuporous, or unconscious and shows obvious signs of life:

1. Handle gently and immobilize the patient (reduces the potential for ventricular fibrillation).

2. Consider aeromedical evacuation to prevent jostling.

3. Maintain the patient in a horizontal position to avoid orthostatic hypotension.

4. Do not encourage ingestion of oral fluids. The small contribution to hydration and rewarming is outweighed by the risk for aspiration.

5. Do not massage or vigorously manipulate the patient’s extremities.

6. Provide oxygenation commensurate with the patient’s clinical condition.

a. Options include simple administration of oxygen by nasal cannula or face mask, bag-valve-mask ventilation, or endotracheal intubation.

b. If endotracheal intubation is performed, avoid overinflation of the tube cuff with frigid air, which may later expand and obstruct the tube or cause laryngeal injury as the air within the cuff warms.

7. If IV or IO capability exists, initiate access and administer 250 to 500 mL of heated (37° to 41° C [98.6° to 105.8° F]) 5% dextrose in normal saline (NS) solution. If NS solution is unavailable, use any crystalloid, preferably containing dextrose. However, avoid lactated Ringer’s solution because a cold liver poorly metabolizes lactate. The IV fluid can be warmed by any of the following techniques:

a. Use commercially available products, such as the Wilderness IV Warmer and the Ultimate Hot Pack.

b. Place the IV bag underneath the patient’s back, shoulder, or buttocks.

c. Tape heat-producing packets (e.g., hand warmers, meals ready to eat [MRE] heating packs) to the fluid bag.

d. If heated fluids are unavailable, administer fluid heated to the rescuer’s skin temperature (i.e., >86° F [30° C]). This can be accomplished by carrying plastic fluid-filled bags next to the skin during rescue.

8. Use a fluid bag–compressor inflatable cuff.

9. Consider treatment of hypoglycemia, specifically, therapy with 50% dextrose, 25 g IV or IO.

10. Stabilize the patient’s body temperature.

a. Remove wet clothing, and replace it with dry clothing; insulate the patient from above and below.

b. Be cautious with immersion warming in the field because this may cause core temperature afterdrop.

c. Place hot water bottles or padded heat packs in the axillae and groin area and around the neck. Wrap hot water bottles with insulation (e.g., fleece) to prevent thermal burns.

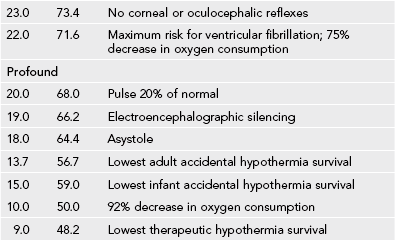

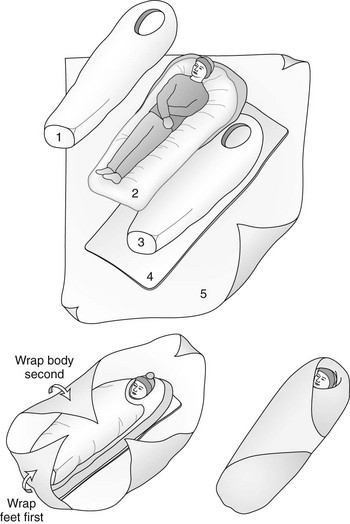

d. Initiate external warming using blankets, sleeping bags, or shelter. Patients in the field should be wrapped. The wrap starts with a large plastic sheet on which is placed an insulated sleeping pad. A layer of blankets, sleeping bag, or bubble wrap insulating material is laid over the sleeping bag. The patient is placed on the insulation, the heating bottles are put in place along with fluid-filled bags intended for infusion, and the entire package is wrapped layer over layer. The plastic is the final closure. The face should be partially covered, but a tunnel should be created to allow access for breathing and monitoring of the patient (see Fig. 3-1).

e. A warmed-air–circulating heater pack may be used as an adjunct.

f. Consider inhalation with humidification if possible rewarming if available and personnel are well trained in its use.

Severe Hypothermia

Severe hypothermia is diagnosed when core body temperature falls below 28° C (82.4° F).

Treatment

1. Determine if the patient is breathing.

a. Because chest rise may be difficult to discern, listen and feel carefully around the nose and mouth. A “vapor trail” is usually absent. If a stethoscope is available, auscultate for breath sounds.

b. If the patient is not breathing, assist with oxygenation and ventilation by endotracheal intubation or supraglottic airway device (e.g., laryngeal mask airway, King airway).

c. Avoid overzealous assistance of ventilation, which can induce hypocapnic ventricular irritability.

2. Feel for a pulse (best done at the carotid or femoral arteries). Do this for at least 1 minute. If there is no palpable pulse and a stethoscope is available, auscultate for heart sounds. If a portable ultrasound device is available, assess for heart wall motion.

3. Avoid unnecessary chest compressions of CPR, because these may initiate ventricular fibrillation and be catastrophic.

4. Apply a cardiac monitor-defibrillator.

a. If ventricular fibrillation or asystole is determined, defibrillate one time with 2 watt sec/kg up to 200 watt sec. Use benzoin to affix nonadherent electrodes. Do not defibrillate if electrical complexes indicating an organized rhythm are seen on a cardiac monitor. Defibrillation rarely succeeds below a core temperature of 30° C (86° F). If the patient remains in asystole or ventricular fibrillation, begin CPR.

b. If electrical complexes indicating an organized rhythm are seen on a cardiac monitor, assess for a central pulse to determine if the patient has pulseless electrical activity. This is a difficult judgment call. The patient may have a low blood pressure that cannot be appreciated by the rescuer, in which case the chest compressions of CPR might initiate ventricular fibrillation.

4. If resuscitation is not successful in the field, continue warming and CPR until the patient arrives at a hospital or you cannot continue because of fatigue or danger to yourself.

5. If the resuscitation is successful, follow the preceding protocol for moderate or severe hypothermia.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

1. Carefully determine the patient’s cardiopulmonary status.

a. Feel for a carotid or femoral pulse for at least 1 minute.

b. Watch the chest for motion (breathing) for at least 30 seconds.

c. Listen with the ear close to the patient’s nose for breathing for at least 30 seconds.

2. If a hypothermic patient has any sign of life, do not begin the chest compressions of CPR, even if a peripheral pulse cannot be appreciated.

a. If the patient is breathing at a suboptimal rate, assist with mouth-to-mouth or mouth-to-mask technique.

b. Perform endotracheal intubation or place a supraglottic airway for standard indications (oxygenation, ventilation, and protection of the airway).

4. If the patient is without any sign of life, begin standard CPR.

a. A single rescuer who is fatigued may continue at slower rates of compression and artificial breathing with some expectation that these may be adequate because of the protective effects of hypothermia.

b. Continue CPR until the patient is brought to a hospital, the rescuer is fatigued, or the rescuer is endangered.

5. Do not begin CPR if the patient has suffered obviously fatal injuries.

a. A serum potassium (K+) level greater than 10 mEq/L in the presence of hypothermia is a strong prognostic marker for death.

b. Remember that a patient who appears dead may recover from hypothermia. Fixed and dilated pupils, dependent lividity, rigid muscles, and absence of detectable vital signs may be seen in patients with profound hypothermia. If in doubt, begin the resuscitation.