Chapter 45 Hyponatremia and Hypernatremia

3 Does hyponatremia simply mean there is too little sodium in the body?

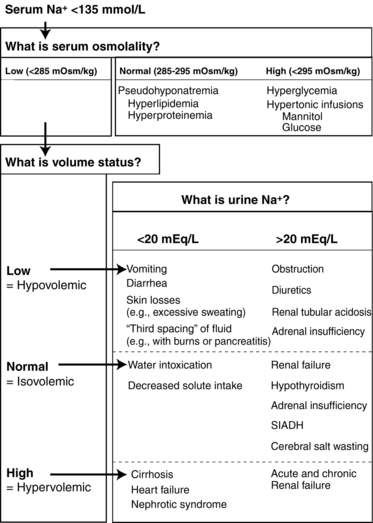

No. The serum sodium concentration is not a reflection of the total body sodium content; instead, it is more representative of changes in the total body water. With hyponatremia, defined as serum sodium level less than 135 mEq/L, there is too much total body water relative to the amount of total body sodium, thereby lowering its concentration. Despite this key observation, the serum sodium concentration is not a reflection of volume status, and it is possible for hyponatremia to develop in states of volume depletion, euvolemia, and volume excess. Assessing a patient’s volume status is therefore the key step in identifying the underlying cause of hyponatremia (Fig. 45-1). Helpful physical findings include tachycardia, dry mucous membranes, orthostatic hypotension, increased skin turgor (associated with hypovolemia) or edema, an S3 gallop, jugular venous distention, and ascites (present in hypervolemic states).

10 What is the difference between acute and chronic hyponatremia?

Acute hyponatremia: A distinct entity in terms of morbidity, mortality, and treatment strategies. Acute hyponatremia most commonly occurs in the hospital (frequently in the postoperative setting), in psychogenic polydipsia, and in elderly women taking thiazide diuretic agents.

Acute hyponatremia: A distinct entity in terms of morbidity, mortality, and treatment strategies. Acute hyponatremia most commonly occurs in the hospital (frequently in the postoperative setting), in psychogenic polydipsia, and in elderly women taking thiazide diuretic agents.

Chronic hyponatremia: Chronic hyponatremia is defined as hyponatremia lasting longer than 48 hours. The majority of patients who are seen by physicians or emergency departments with hyponatremia should be assumed to have chronic hyponatremia.

Chronic hyponatremia: Chronic hyponatremia is defined as hyponatremia lasting longer than 48 hours. The majority of patients who are seen by physicians or emergency departments with hyponatremia should be assumed to have chronic hyponatremia.

20 What are some helpful formulas for assessing sodium abnormalities?

Serum osmolality = 2 [Na+] + Glucose/18 + Blood urea nitrogen/2.8 + Ethyl alcohol/4.6

Serum osmolality = 2 [Na+] + Glucose/18 + Blood urea nitrogen/2.8 + Ethyl alcohol/4.6

Total body water (TBW) = Body weight × 0.6 (for men)

Total body water (TBW) = Body weight × 0.6 (for men)

TBW = Body weight × 0.5 (for women and the elderly)

TBW excess in hyponatremia = TBW (1 − [Serum Na+]/140)

TBW excess in hyponatremia = TBW (1 − [Serum Na+]/140)

TBW deficit in hypernatremia = TBW (Serum [Na+]/140 − 1)

TBW deficit in hypernatremia = TBW (Serum [Na+]/140 − 1)

Expected change in serum sodium level after 1 L D5W = (Serum [Na+])/(TBW + 1)

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Stuart Senkfor, MD, and Tomas Berl, MD.

Key Points Useful Diagnostic Tests in Hyponatremia

1. Serum osmolality measurement is useful in the diagnosis of hyponatremia.

2. Determination of volume status is necessary.

3. If urine osmolality is inappropriately high, it is easier to differentiate causes of euvolemic hyponatremia. High urine osmolality implies inappropriate levels of ADH or ADH-like hormones.

4. Urine sodium concentration needs to be interpreted with caution in cases of renal failure.

1 Adrogue H.J., Madias N.E. Hyponatremia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1581–1589.

2 Anderson R.J., Chung H.M., Kluge R., et al. Hyponatremia: a prospective analysis of its epidemiology and the pathogenetic role of vasopressin. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:164–168.

3 Budisavljevic M.N., Stewart L., Sahn S.A., et al. Hyponatremia associated with 3-4-methylenedioxymethylamphetamine (“Ectasy”) abuse. Am J Med Sci. 2003;326:89–93.

4 Elhassan E.A., Schrier R.W. Hyponatremia: diagnosis, complications and management including V2 receptor antagonists. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:161–168.

5 Ellison D.H., Berl T. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2064–2072.

6 Hillier T.A., Abbott R.D., Barrett E.J. Hyponatremia: evaluating the correction factor for hyperglycemia. Am J Med. 1999;106:399–403.

7 Lin M., Liu S.J., Lim I.T. Disorders of water imbalance. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:749–770.

8 Milionis H.J., Liamis G.L., Elisaf M.S. The hyponatremic patient: a systematic approach to laboratory diagnosis. Can Med Assoc J. 2002;166:1056–1062.

9 Moritz M.L., Ayus J.C. The pathophysiology and treatment of hyponatremic encephalopathy: an update. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:2486–2491.

10 Sterns RH: Osmotic demyelination syndrome and overly rapid correction of hyponatremia: www.uptodate.com. Accessed February 23, 2011

11 Verbalis J. Disorders of body water homeostasis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17:471–503.

12 Verbalis J.G., Berl T. Disorders of water balance. In: BM Brenner, ed. Brenner and Rector’s The Kidney. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007:460–504.