Hyponatraemia

pathophysiology

Development of hyponatraemia

Loss of sodium. Sodium is the main extracellular cation and plays a critical role in the maintenance of blood volume and pressure, by osmotically regulating the passive movement of water. Thus when significant sodium depletion occurs, water is lost with it, giving rise to the characteristic clinical signs associated with ECF compartment depletion. Primary sodium depletion should always be actively considered if only to be excluded; failure to do so can have fatal consequences.

Loss of sodium. Sodium is the main extracellular cation and plays a critical role in the maintenance of blood volume and pressure, by osmotically regulating the passive movement of water. Thus when significant sodium depletion occurs, water is lost with it, giving rise to the characteristic clinical signs associated with ECF compartment depletion. Primary sodium depletion should always be actively considered if only to be excluded; failure to do so can have fatal consequences.

Water retention. Retention of water in the body compartments dilutes the constituents of the extracellular space including sodium, causing hyponatraemia. Water retention occurs much more frequently than sodium loss, and where there is no evidence of fluid loss from history or examination, water retention as the mechanism becomes a near-certainty.

Water retention. Retention of water in the body compartments dilutes the constituents of the extracellular space including sodium, causing hyponatraemia. Water retention occurs much more frequently than sodium loss, and where there is no evidence of fluid loss from history or examination, water retention as the mechanism becomes a near-certainty.

Water retention

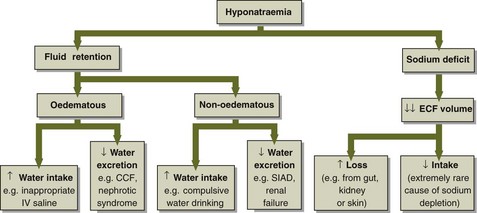

The causes of hyponatraemia due to water retention are shown in Figure 8.1. Water retention usually results from impaired water excretion and rarely from increased intake (compulsive water drinking). Most patients who are hyponatraemic due to water retention have the so-called syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIAD). The SIAD is encountered in many conditions, e.g. infection, malignancy, chest disease, and trauma (including surgery); it can also be drug-induced. SIAD results from the inappropriate secretion of AVP. Whereas in health the AVP concentration fluctuates between 0 and 5 pmol/L due to changes in osmolality, in SIAD huge (non-osmotic) increases (up to 500 pmol/L) can be seen. Powerful non-osmotic stimuli include hypovolaemia and/or hypotension, nausea and vomiting, hypoglycaemia, and pain. The frequency with which SIAD occurs in clinical practice mirrors the widespread prevalence of these stimuli. It should be stressed that the increase in AVP secretion induced by, say, hypovolaemia is an entirely appropriate mechanism to try to restore blood volume to normal. The term ‘inappropriate’ in SIAD is used specifically to indicate that the secretion of AVP is inappropriate for the serum osmolality.

AVP has other effects in the body aside from regulating renal water handling (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1

Sodium loss

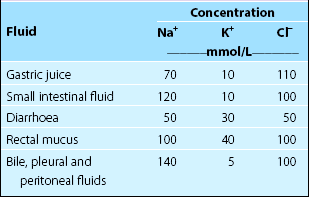

The causes of hyponatraemia due to sodium loss are shown in Figure 8.1. Sodium depletion effectively occurs only when there is pathological sodium loss, either from the gastrointestinal tract or in urine. Gastrointestrinal losses (Table 8.2) commonly include those from vomiting and diarrhoea; in patients with fistulae due to bowel disease, losses may be severe. Urinary loss may result from mineralocorticoid deficiency (especially aldosterone) or from drugs that antagonize aldosterone, e.g. spironolactone.

Sodium depletion – a word of caution

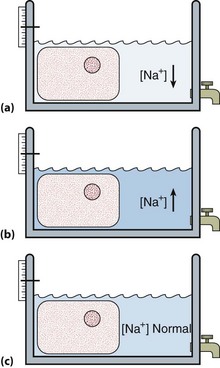

Not all patients with sodium depletion are hyponatraemic. Patients with sodium loss due to an osmotic diuresis may become hypernatraemic if more water than sodium is lost. Life-threatening sodium depletion can also be present with a normal serum sodium concentration. In short, the serum sodium concentration does not of itself provide any information about the presence or severity of sodium depletion (Fig 8.2). The history and clinical examination are much more useful in this regard.

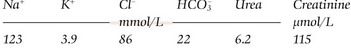

Pseudohyponatraemia

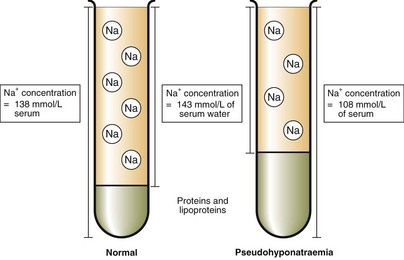

Hyponatraemia is sometimes reported in patients with severe hyperproteinaemia or hyperlipidaemia. In such patients, the increased amounts of protein or lipoprotein occupy more of the plasma volume than usual, and the water less (Fig 8.3). Sodium and the other electrolytes are distributed in the water fraction only, and these patients have a normal sodium concentration in their plasma water. However, many of the methods used in analytical instruments measure the sodium concentration in the total plasma volume, and take no account of a water fraction that occupies less of the total plasma volume than usual. An artefactually low sodium result may thus be obtained in these circumstances. Such pseudohyponatraemia should be suspected if there is a discrepancy between the degree of apparent hyponatraemia and the symptoms that one might expect due to the low sodium concentration (see pp. 18–19), e.g. a patient with a sodium concentration of 110 mmol/L who is completely asymptomatic. The serum osmolality is unaffected by any changes in the fraction of the total plasma volume occupied by proteins or lipids, since they are not dissolved in the water fraction and, therefore, do not make any contribution to the osmolality. A normal serum osmolality in a patient with severe hyponatraemia is, thus, strongly suggestive of pseudohyponatraemia. This can be assessed formally by calculating the osmolal gap, the difference between the measured osmolality and the calculated osmolality (see p. 13).