Hyponatraemia

assessment and management

Clinical assessment

Clinicians assessing a patient with hyponatraemia should ask themselves several questions.

Severity

Mechanism

Clinical examination

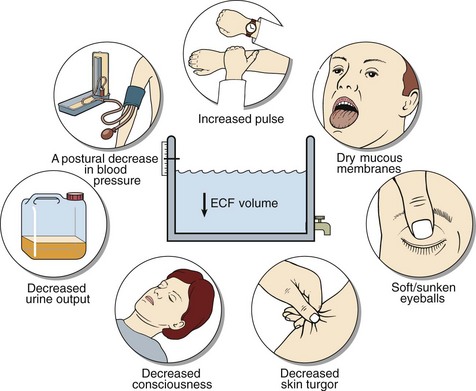

The clinical signs characteristic of ECF and blood volume depletion are shown in Figure 9.1. These signs should always be looked for; in hyponatraemic patients they are diagnostic of sodium depletion. If they are present in the recumbent state, severe life-threatening sodium depletion is present and urgent treatment is needed. In the early phases of sodium depletion postural hypotension may be the only sign. By contrast, even when water retention is strongly suspected, there may be no clinical evidence of water overload. There are two good reasons for this. Firstly, water retention due to the SIAD (the most frequent explanation) occurs gradually, often over weeks or even months. Secondly, the retained water is distributed evenly over all body compartments; thus the increase in the ECF volume is minimized.

Biochemistry

Sodium depletion is diagnosed largely on clinical grounds, whereas in patients with suspected water retention, history and examination may be unremarkable. However, both sodium depletion and SIAD produce a similar biochemical picture (Table 9.1) with reduced serum osmolality reflecting hyponatraemia, and a high urine osmolality reflecting AVP secretion. In sodium depletion, AVP secretion is appropriate to the hypovolaemia resulting from sodium and water loss; in SIAD it is inappropriate (non-osmotic). Urinary sodium excretion is often increased in SIAD (a hypervolaemic state). It may be low or high in sodium depletion depending on whether the pathological loss is from gut or kidney.

Table 9.1

Clinical and biochemical features of sodium depletion and SIAD

| Sodium depletion | Water retention | |

| Symptoms* | Often present, e.g. dizziness, light-headedness, collapse | Usually absent |

| Signs* | Often present. Signs of volume depletion, e.g. hypotension (see Fig 9.1) | Usually absent Oedema |

| Clinical value of signs | Diagnostic of sodium depletion if present | Oedema narrows differential diagnosis |

| Clinical course | Rapid | Slow |

| Serum osmolality | Low | Low |

| Urine osmolality | High | High |

| Urinary sodium excretion | Low if gut/skin loss of sodium Variable if kidney loss |

Variable but usually increased |

| Water balance | Too little | Too much |

| Sodium balance | Too little | Normal Too much if oedema |

| Treatment aim | Replace sodium | Restrict water Natriuresis if oedema |

*Relating specifically to the mechanism. There may well be symptoms/signs relating to the underlying cause.

Oedema

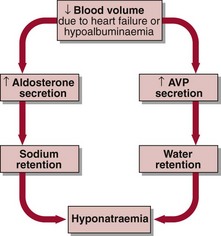

Oedema is an accumulation of fluid in the interstitial compartment. It is readily elicited by looking for pitting in the lower extremities of ambulant patients (Fig 9.2), or in the sacral area of recumbent patients. It arises from a reduced effective circulating blood volume, due either to heart failure or hypoalbuminaemia.

Fig 9.2 Pitting oedema. After depressing the skin firmly for a few seconds an indentation or pit is seen.

The response to this is secondary hyperaldosteronism. Aldosterone causes sodium (and water) retention, thus expanding the ECF volume. Patients with oedema become hyponatraemic despite sodium retention because the effective hypovolaemia also stimulates AVP secretion, resulting in additional water retention (Fig 9.3).