Hypoglycaemia

Clinical effects

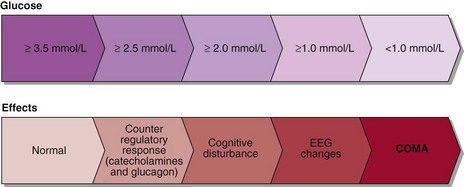

Hypoglycaemia normally leads to suppression of insulin secretion, an increase in catecholamine secretion and stimulation of glucagon, cortisol and growth hormone. The catecholamine surge accounts for the signs and symptoms most commonly seen in hypoglycaemia, i.e. sweating, shaking, tachycardia as well as feeling weak, jittery and nauseated. Hypoglycaemia decreases the glucose fuel supply to the brain and symptoms of cognitive impairment must always be sought since they reflect neuroglycopenia. They include confusion, poor concentration, detachment and, in more severe instances, convulsions and coma. The clinical effects of hypoglycaemia are summarized in Figure 34.1.

Assessment

The diagnosis of hypoglycaemia is established when three criteria (‘Whipple’s triad’) are satisfied.

There must be symptoms consistent with hypoglycaemia.

There must be symptoms consistent with hypoglycaemia.

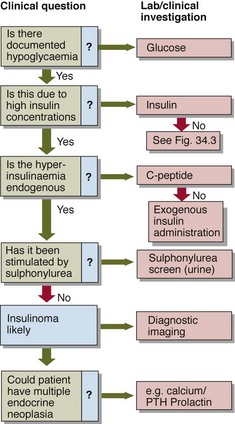

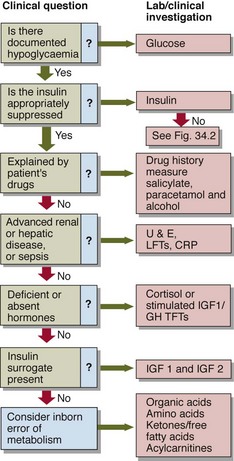

As a preliminary step to formal assessment, patients may be supplied with blood spot strips and asked to take fingerprick blood samples during symptomatic episodes. It may be necessary to try to precipitate symptoms, e.g. by prolonged fasting. If a blood sample is being collected for glucose analysis during a symptomatic episode, an additional sample should be collected simultaneously for insulin. This need not be analysed at the time, or indeed at all unless hypoglycaemia is confirmed, but the insulin level critically alters the differential diagnosis of hypoglycaemia (Figs 34.2 and 34.3).

Specific causes of hypoglycaemia

Fasting hypoglycaemia

Causes of fasting hypoglycaemia include:

Insulinoma. These insulin-producing β-cell tumours of the pancreas may be isolated or part of the wider multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome (see pp. 142–143). Insulin-induced weight gain is a characteristic feature. Localization of the tumour may be difficult.

Insulinoma. These insulin-producing β-cell tumours of the pancreas may be isolated or part of the wider multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndrome (see pp. 142–143). Insulin-induced weight gain is a characteristic feature. Localization of the tumour may be difficult.

Malignancy. Hypoglycaemia may be found with any advanced malignancy. Some tumours, e.g. retroperitoneal sarcomas, cause hypoglycaemia by producing insulin-like growth factors.

Malignancy. Hypoglycaemia may be found with any advanced malignancy. Some tumours, e.g. retroperitoneal sarcomas, cause hypoglycaemia by producing insulin-like growth factors.

Hepatic and renal disease. Both the liver and kidneys are capable of gluconeogenesis. Hypoglycaemia is occasionally a feature of advanced hepatic or renal impairment, but this is not usually a diagnostic dilemma.

Hepatic and renal disease. Both the liver and kidneys are capable of gluconeogenesis. Hypoglycaemia is occasionally a feature of advanced hepatic or renal impairment, but this is not usually a diagnostic dilemma.

Addison’s disease. Given the fact that glucocorticoids antagonize the actions of insulin, it should not be surprising that hypoglycaemia is occasionally a feature of adrenal insufficiency.

Addison’s disease. Given the fact that glucocorticoids antagonize the actions of insulin, it should not be surprising that hypoglycaemia is occasionally a feature of adrenal insufficiency.

Sepsis. Overwhelming sepsis may be associated with hypoglycaemia; the mechanism is unclear.

Sepsis. Overwhelming sepsis may be associated with hypoglycaemia; the mechanism is unclear.

Reactive hypoglycaemia

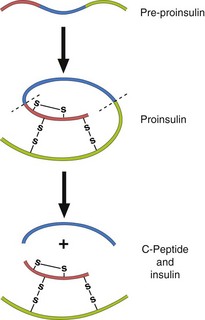

Insulin-induced. Inappropriate or excessive insulin predictably produces hypoglycaemia. Occasionally it is important to distinguish between exogenous insulin (administered by the patient or someone else) and endogenous insulin. Standard assays for insulin cannot distinguish between the two kinds. However, insulin and its associated connecting peptide (or C-peptide) are secreted by the islet cells in equimolar amounts, and thus measurement of C-peptide along with insulin can differentiate between hypoglycaemia due, for example, to an insulinoma (high C-peptide) and that due to exogenous insulin (low C-peptide) (Fig 34.4).

Insulin-induced. Inappropriate or excessive insulin predictably produces hypoglycaemia. Occasionally it is important to distinguish between exogenous insulin (administered by the patient or someone else) and endogenous insulin. Standard assays for insulin cannot distinguish between the two kinds. However, insulin and its associated connecting peptide (or C-peptide) are secreted by the islet cells in equimolar amounts, and thus measurement of C-peptide along with insulin can differentiate between hypoglycaemia due, for example, to an insulinoma (high C-peptide) and that due to exogenous insulin (low C-peptide) (Fig 34.4).

Drug-induced. Oral hypoglycaemics, e.g. sulphonylureas, can produce hypoglycaemia. Urinary screens for sulphonylureas exist. Other drugs that occasionally give rise to hypoglycaemia less predictably include salicylate, paracetamol and β-blockers. More importantly, the last may also mask the patient’s awareness of hypoglycaemia, by blunting the β-effect of adrenaline and reducing or eliminating the warning symptoms such as palpitation or tremor.

Drug-induced. Oral hypoglycaemics, e.g. sulphonylureas, can produce hypoglycaemia. Urinary screens for sulphonylureas exist. Other drugs that occasionally give rise to hypoglycaemia less predictably include salicylate, paracetamol and β-blockers. More importantly, the last may also mask the patient’s awareness of hypoglycaemia, by blunting the β-effect of adrenaline and reducing or eliminating the warning symptoms such as palpitation or tremor.

Alcohol. Hypoglycaemia is not uncommon in alcoholic patients. Mechanisms include inhibition of gluconeogenesis, malnutrition and liver disease.

Alcohol. Hypoglycaemia is not uncommon in alcoholic patients. Mechanisms include inhibition of gluconeogenesis, malnutrition and liver disease.

‘Dumping syndrome’. Accelerated gastric emptying following gastric resection may result in the rapid absorption of large amounts of glucose with a resultant surge of insulin release. Smaller, more frequent meals may help to minimize this phenomenon.

‘Dumping syndrome’. Accelerated gastric emptying following gastric resection may result in the rapid absorption of large amounts of glucose with a resultant surge of insulin release. Smaller, more frequent meals may help to minimize this phenomenon.

Diabetic patients

In diabetic patients, hypoglycaemia is rarely a diagnostic dilemma. Precipitating factors include:

Neonatal hypoglycaemia

Certain groups of neonates are especially vulnerable to hypoglycaemia:

Small-for-gestational-age infants. Depleted glycogen stores and impaired gluconeogenesis contribute.

Small-for-gestational-age infants. Depleted glycogen stores and impaired gluconeogenesis contribute.

Babies of diabetic mothers. A fetus that is exposed to maternal hyperglycaemia will develop hyperplasia of the islet cells and associated hyperinsulinaemia. After delivery, the neonate is unable to suppress its high insulin levels that are now inappropriate, and hypoglycaemia results.

Babies of diabetic mothers. A fetus that is exposed to maternal hyperglycaemia will develop hyperplasia of the islet cells and associated hyperinsulinaemia. After delivery, the neonate is unable to suppress its high insulin levels that are now inappropriate, and hypoglycaemia results.

Nesidioblastosis. Hyperplasia of the islet cells may develop even when the mother is not diabetic; the reasons are unclear.

Nesidioblastosis. Hyperplasia of the islet cells may develop even when the mother is not diabetic; the reasons are unclear.

Inborn errors of metabolism. Many inborn errors are associated with hypoglycaemia. Fatty acid oxidation defects, glycogen storage diseases and galactosaemia are important examples.

Inborn errors of metabolism. Many inborn errors are associated with hypoglycaemia. Fatty acid oxidation defects, glycogen storage diseases and galactosaemia are important examples.