Chapter 62 Hypoglossal Facial Anastomosis

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Connection of a graft with the normal facial nerve followed by redirection of some of these fibers to the paralyzed side is termed cross-facial grafting. This method can provide some symmetry of movement, while avoiding other motor deficits. This procedure partially compromises the normal nerve, however, and provides a scant supply of neural elements to the recipient muscles, leading to inconsistent results.1,2 As a consequence, this procedure has not met with widespread acceptance.3,4 Combinations of cross-facial grafting and traditional nerve substitutions may also be employed.5–8

Nerve/muscle pedicle grafts such as temporalis muscle transfer have been used with some success, but have also yielded inconsistent results.9 Because the results of nerve/muscle pedicle grafts and cross-facial grafts have been disappointing, modifications of these procedures have been developed that use combination cross-facial grafting and microvascular free muscle flaps for facial reanimation.9,10 More recently, a modification of the traditional temporalis transfer has been used that incorporates the temporalis tendon alone instead of a portion of the muscle.11

PATIENT SELECTION

In cases of known facial nerve discontinuity in which direct repair or grafting is impossible, the CN XII/VII anastomosis should be performed as soon as reasonably possible. Muscle atrophy and degeneration proceed rapidly after denervation.12 Early repair provides axonal growth to the muscles and limits the amount of muscle degeneration.

The severed nerve also begins to experience fibrosis.13,14 In early anastomoses, new axons fill the nerve sheath before fibrosis and potentially allow a greater supply of axons to the muscles. Although earlier anastomosis gives a better functional result, the CN XII/VII anastomosis is also effective after a prolonged denervation and should be considered up to 2.5 years after injury.4,15 Return of function can occur 4.5 years after injury.16

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

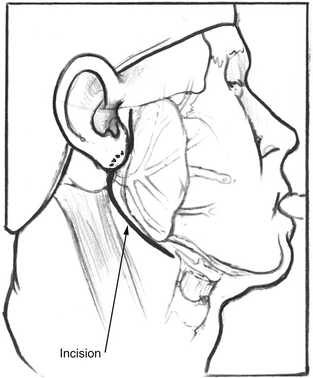

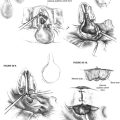

After satisfactory general endotracheal anesthesia has been obtained with the patient in the supine position, the neck is extended, and the face is turned toward the side opposite the paralysis. The ear, face, and neck are prepared and draped using sterile technique. A standard lazy S parotidectomy incision is made in the preauricular crease and extended behind the lobule and then anteriorly about 2 cm below the angle of the mandible (Fig. 62-1). In cases where the patient has had a prior postauricular incision for craniotomy, the postauricular incision may also be used for the superior aspect of the incision. This is particularly true if a mobilization of the facial nerve out of the fallopian canal is planned.

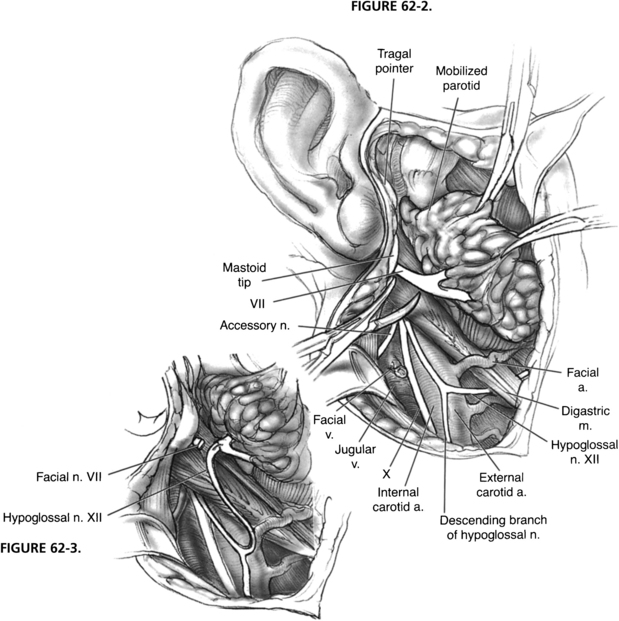

The hypoglossal nerve is identified by retracting the sternocleidomastoid muscle posteriorly and exposing the great vessels of the neck. The posterior belly of the digastric muscle is retracted superiorly, and the hypoglossal nerve is found coursing inferiorly with the great vessels and then turning anteriorly as it supplies the ansa cervicalis, which descends in the carotid sheath (Fig. 62-2). The hypoglossal nerve is followed anteriorly and medially as it enters the tongue muscle. The nerve is freed from its fascial attachments in the neck. The network of veins and arteries entering the internal jugular vein and external carotid artery should be controlled during this maneuver. After the nerve is freed from its attachments, it is divided as far anteriorly as is possible to gain sufficient length. The free hypoglossal nerve is rotated superiorly. Directing the nerve medial to the digastric muscle in this rotation gives the most length, but is unnecessary for a satisfactory anastomosis.

NERVE GROWTH FACTORS AND CONDUITS

Nerve grafts are the traditional technique to bridge the gap between two ends of nerve to be anastomosed. Because nerve repairs need to be tension-free, grafts are required if the ends of the nerve cannot be freely coapted. If a way could be developed to bridge this gap without using a nerve graft, that would be a potential improvement. Artificial conduits are one potential replacement for nerve grafts.17,18 Collagen tubules have been used to provide a pathway for axonal growth to occur. Other substances that have been used to create conduits include hydrogels19 and collagen-filled vein grafts.20

Several different nerve growth factors have been used to augment nerve graft repair and in collagen tubules. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is an agent that has shown promise when used in collagen tubules or when applied directly to nerve repairs.21,22 Other agents that have been employed include neurotrophin-3 and fibroblast growth factor 1.23 Ciliary neurotrophic factor, a neurocytokine, has also been used in nerve repairs and may increase the rate of recovery over brain-derived neurotrophic factor alone.24

NEWER MODIFICATIONS OF HYPOGLOSSAL-FACIAL ANASTOMOSIS

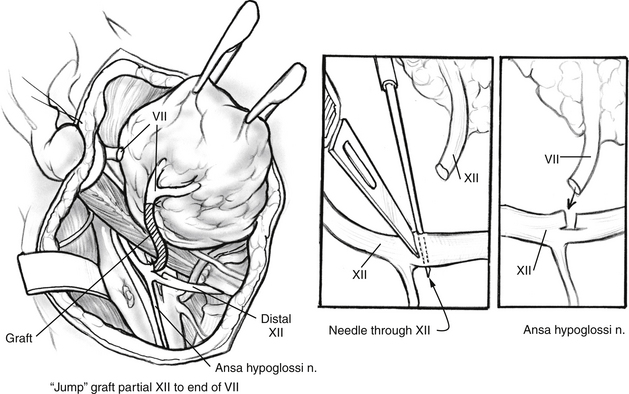

One modification of the standard CN XII/VII crossover graft uses a jump graft between the CN XII and VII. This procedure, as described by May and others,25,26 succeeds in preserving tongue function and reinnervating the facial muscles. The exposure of CN XII and VII is identical to that described earlier (see Fig. 62-2). A 5 cm length of great auricular nerve is harvested. CN XII is cut through on half of its diameter in a beveled manner. The incision should be made in a portion of the nerve distal to the divergence of the ansa cervicalis to avoid tapping the fibers that constitute this nerve (Fig. 62-4, inset). Stimulation of CN XII with a nerve stimulator proximal to the partial transection should confirm preservation of tongue function.

The great auricular graft and the distal segment of the facial nerve are prepared for anastomosis in the manner described for the standard CN XII/VII crossover. The graft is sutured to the proximal segment of the partially severed CN XII. The other end of the graft is sutured to the prepared distal end of the facial nerve (see Fig. 62-4). Two or three sutures are used for this connection. Enough length of graft must be used to avoid tension at the sites of anastomosis. The wound is closed as in the standard procedure. The patient is usually kept in the hospital overnight and discharged the following morning after removal of the drain. Although the patient may have some trouble with pooling of food in the ipsilateral oral vestibule, no special diet is necessary.

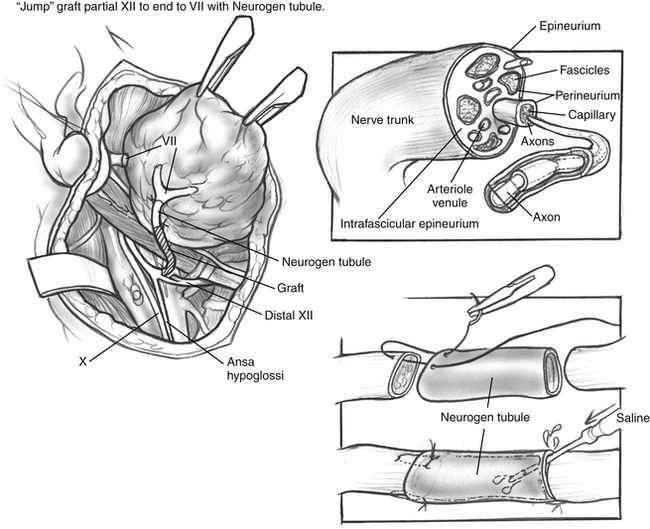

In another variation of the jump graft hypoglossal/facial anastomosis, a collagen tubule may be used as an adjunct to the anastomosis between the facial nerve and the jump graft (Fig. 62-5). Collagen tubules, described previously, may be used to facilitate direct coaptation of the nerve ends, or saline may be placed in the tubule between the nerve ends. A single epineurial suture is used to connect the nerve graft to the collagen tubule (see Fig. 62-5, inset).

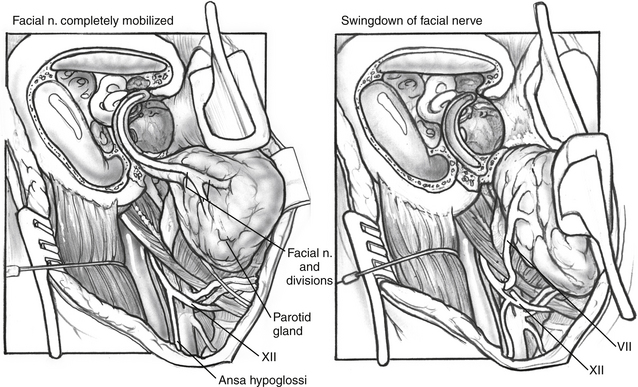

End-to-Side Anastomosis via Translocation of Facial Nerve from the Fallopian Canal

A more recent technique consists of rerouting the facial nerve from the fallopian canal and connecting it directly to the hypoglossal nerve through an end-to-side anastomosis.27 In this technique, the facial nerve is decompressed from the stylomastoid foramen inferiorly to the geniculate ganglion superiorly. The greater superficial petrosal nerve is transected at the geniculate ganglion, and the facial nerve is mobilized inferiorly. The nerve itself is traced through the periosteum of the stylomastoid foramen until the pes anserinus is reached (Fig. 62-6). When the pes is reached, the nerve is of sufficient length for the proximal end of the nerve to be anastomosed to a partial (“end-to-side”) transection of the hypoglossal nerve, either through a direct anastomosis or with a collagen tubule (see Fig. 62-6).

RESULTS

A patient with facial paralysis who is considered a candidate for CN XII/VII crossover should be counseled about the expected results from this procedure. The patient cannot expect normal facial function for several reasons.3,4,28–32 As in a direct nerve repair, the axons directed to specific muscles find a random path. The muscles of the face include agonists and antagonists for various expressions and movements. When agonist and antagonist muscles are simultaneously stimulated, the result is a canceling effect. This effect is similar to that occurring during stimulation of a flexor and extensor muscle at the same time. The hypoglossal nerve controls different muscle groups, allowing training of facial movement as the patient attempts various tongue motions. The training is successful, but is not helpful in emotional facial response. This procedure does not reproduce the blink reflex, even though some investigators have shown a trigeminal-hypoglossal reflex.28 Problems with xerophthalmia and exposure keratitis may require adjunctive lid procedures, such as a palpebral spring or gold weight lid implant.

Within 4 to 6 months, the patient begins to see tone in the muscles and a resting symmetry.3,4,13,32 With a rehabilitation program, volitional movement is possible, allowing the patient to smile with tongue movement. Electromyographic feedback–enhanced rehabilitation has shown some additional benefits.1,13,33 Because many facial movements are also coordinated with oral function, the CN XII/VII anastomosis improves the patient’s ability to eat by providing tension to the buccal area and keeping the bolus in the oral vestibule. The natural interaction between the facial and hypoglossal nerves in eating, swallowing, and speaking facilitates the rehabilitation seen with this crossover graft as opposed to the accessory or phrenic nerve.

Because of the nonselective nature of reinnervation, movement of the face results in synkinesis and mass movement that varies from patient to patient. Synkinesis can be reduced by exercise and biofeedback early in recovery.33 Selective section of branches of the facial nerve is also useful in severe cases, as is the use of selective botulinum toxin injections.34

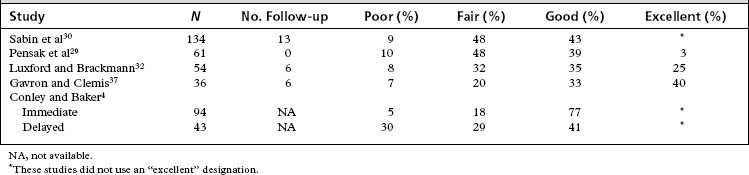

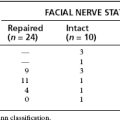

Because the function gained by reinnervation procedures cannot compare with normal facial function, a different method of grading facial function is used in evaluation of the results of the CN XII/VII crossover. A grading system used in a prior analysis of CN XII/VII crossover patients in our facility is presented in Table 62-1. Although the methods used to evaluate results vary from study to study, we have extrapolated the grading system in Table 62-1 to provide the results from several sizable studies (Table 62-2). This analysis should give the reader a good idea of reasonable expectations from this procedure.

TABLE 62-1 Facial Nerve Function after Cranial Nerve XII-VII Anastomosis: Quality of Return Criteria before House-Brackmann Grading Scale

| Poor | Tone without symmetry or movement |

|---|---|

| Fair | Tone, symmetry, limited movement |

| Good | Tone, symmetry, fair movement, moderate synkinesis |

| Excellent | Tone, symmetry, good movement, mild synkinesis |

From Luxford WM, Brackmann DE: Facial nerve substitution: A review of sixty-six cases. Am J Otol Suppl 55-57, 1985.

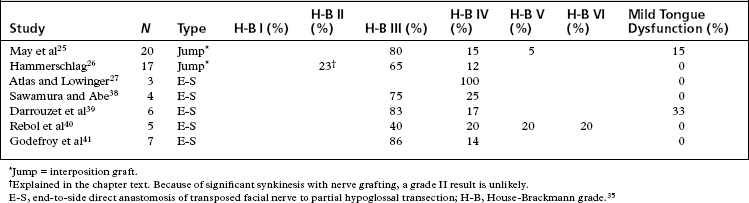

More recent studies, particularly studies reporting on results for jump interposition grafts or translocation of the facial nerve with end-to-side anastomosis, use the House-Brackmann grading scale for result reporting.35 Table 62-3 shows results from more recent studies using either jump grafting or end-to-side anastomosis. The patients in these studies were divided between early intervention (<12 months) and late intervention (>12 months, but generally <24 months), and had similar outcomes. Generally, the best result to be expected on the House-Brackmann grading scale with any nerve grafting procedure is a grade III result. This result requires movement of the forehead. Almost all patients have significant synkinesis after hypoglossal/facial anastomosis, rendering grade III the best result to be expected.

The deficit incurred in the sacrifice of one hypoglossal nerve is easily overcome by most patients.4,13,32 Initially, some pooling of food in the lingual sulcus is problematic. As the buccal musculature regains tone, and as the ipsilateral tongue atrophies, this problem lessens. In Conley and Baker’s large series,4 about one fourth of the patients experienced severe or minimal atrophy, and the remaining half experienced moderate atrophy. Very few patients had trouble with speech. The best results in regaining facial function and overcoming the CN XII deficit were seen with early anastomosis compared with procedures performed on patients with long-standing paralysis.4

More recent reports indicate that the choice of technique does not cause a difference in facial functional outcomes.36 Methods that preserve tongue function may become preferable to the standard hypoglossal/facial anastomosis.

1. O’Brien B.M., Pederson W.C., Khazanchi R.K., et al. Results of management of facial palsy with microvascular free-muscle transfer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86:12-22.

2. May M. Management of cranial nerves I through VII following skull base surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1980;88:560-575.

3. Chuang D.C., Wei F.C., Noordhoff M.S. “Smile” reconstruction in facial paralysis. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;23:56-65.

4. Conley J., Baker D.C. Hypoglossal-facial nerve anastomosis for reinnervation of the paralyzed face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63:63-72.

5. Yamamoto Y., Sasaki S., Sekido M., et al. Alternative approach using the combined technique of nerve crossover and cross-nerve grafting for reanimation of facial palsy. Microsurgery. 2003;23:251-256.

6. Ueda K., Akiyoshi K., Suzuki Y., et al. Combination of hypoglossal-facial nerve jump graft by end-to-side neurorrhaphy and cross-face nerve graft for the treatment of facial paralysis. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2007;23:181-187.

7. Hadlock T., Sheahan T., Heaton J., et al. Baiting the cross-face nerve graft with temporary hypoglossal hookup. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6:228-233.

8. Yoleri L., Songur E., Mavioglu H., et al. Cross-facial nerve grafting as an adjunct to hypoglossal-facial nerve crossover in reanimation of early facial paralysis: Clinical and electrophysiological evaluation. Ann Plast Surg. 2001;46:301-307.

9. Tucker H.M. Restoration of selective facial nerve function by the nerve-muscle pedicle technique. Clin Plast Surg. 1979;6:293-300.

10. Harrison D.H. The treatment of unilateral and bilateral facial palsy using free muscle transfers. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29:539-549.

11. Byrne P.J., Kim M., Boahene K., et al. Temporalis tendon transfer as part of a comprehensive approach to facial reanimation. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9:234-241.

12. Belal A. Structure of human muscle in facial paralysis: Role of muscle biopsy. In: May M., editor. The Facial Nerve. New York: Thieme; 1986:99-106.

13. Pitty L.F., Tator C.H. Hypoglossal-facial nerve anastomosis for facial nerve palsy following surgery for cerebellopontine angle tumors. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:724-731.

14. Ylikoski J., Hitselberger W.E., House W.F., et al. Degenerative changes in the distal stump of the severed human facial nerve. Acta Otolaryngol. 1981;92(3-4):239-248.

15. Kunihiro T., Kanzaki J., Yoshihara S., et al. Hypoglossal-facial nerve anastomosis after acoustic neuroma resection: Influence of the time anastomosis on recovery of facial movement. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1996;58:32-35.

16. Hitselberger W.E.. Hypoglossal-facial anastomosis. House W.F., Luetje C.M., editors. Acoustic Tumors. vol 2, 1979. University Park Press, Baltimore, 97-103. Management

17. Archibald S.J., Shefner J., Krarup C., et al. Monkey median nerve repaired by nerve graft or collagen nerve guide tube. J Neurosci. 1995;15(5 Pt 2):4109-4123.

18. Archibald S.J., Krarup C., Shefner J., et al. A collagen-based nerve guide conduit for peripheral nerve repair: An electrophysiological study of nerve regeneration in rodents and nonhuman primates. J Comp Neurol. 1991;306:685-696.

19. Belkas J.S., Munro C.A., Shoichet M.S., et al. Peripheral nerve regeneration through a synthetic hydrogel nerve tube. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2005;23:19-29.

20. Lee D.Y., Choi B.H., Park J.H., et al. Nerve regeneration with the use of a poly(l-lactide-co-glycolic acid)-coated collagen tube filled with collagen gel. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2006;34:50-56.

21. Lewin S.L., Utley D.S., Cheng E.T., et al. Simultaneous treatment with BDNF and CNTF after peripheral nerve transection and repair enhances rate of functional recovery compared with BDNF treatment alone. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:992-999.

22. Barde Y.A., Edgar D., Thoenen H. Purification of a new neurotrophic factor from mammalian brain. EMBO J. 1982;1:549-553.

23. Midha R., Munro C.A., Dalton P.D., et al. Growth factor enhancement of peripheral nerve regeneration through a novel synthetic hydrogel tube. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:555-565.

24. Lewin S.L., Utley D.S., Cheng E.T., et al. Simultaneous treatment with BDNF and CNTF after peripheral nerve transection and repair enhances rate of functional recovery compared with BDNF treatment alone. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:992-999.

25. May M., Sobol S.M., Mester S.J. Hypoglossal-facial nerve interpositional-jump graft for facial reanimation without tongue atrophy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:818-825.

26. Hammerschlag P.E. Facial reanimation with jump interpositional graft hypoglossal facial anastomosis and hypoglossal facial anastomosis: Evolution in management of facial paralysis. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(2 Pt 2 Suppl 90):1-23.

27. Atlas M.D., Lowinger D.S. A new technique for hypoglossal-facial nerve repair. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:984-991.

28. Stennert E. I. Hypoglossal facial anastomosis: Its significance for modern facial surgery. II. Combined approach in extratemporal facial nerve reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1979;6:471-486.

29. Pensak M.L., Jackson C.G., Glasscock M.E.III, et al. Facial reanimation with the VII-XII anastomosis: Analysis of the functional and psychologic results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:305-310.

30. Sabin H.I., Bordi L.T., Symon L., et al. Facio-hypoglossal anastomosis for the treatment of facial palsy after acoustic neuroma resection. Br J Neurosurg. 1990;4:313-317.

31. Chang C.G., Shen A.L. Hypoglossofacial anastomosis for facial palsy after resection of acoustic neuroma. Surg Neurol. 1984;21:282-286.

32. Luxford W.M., Brackmann D.E. Facial nerve substitution: A review of sixty-six cases. Am J Otol Suppl. 1985:55-57.

33. Hammerschlag P.E., Brudny J., Cusumano R., et al. Hypoglossal-facial nerve anastomosis and electromyographic feedback rehabilitation. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:705-709.

34. Dressler D., Schonle P.W. Botulinum toxin to suppress hyperkinesias after hypoglossal-facial nerve anastomosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1990;247:391-392.

35. House J.W., Brackmann D.E. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93:146-147.

36. Guntinas-Lichius O., Streppel M., Stennert E. Postoperative functional evaluation of different reanimation techniques for facial nerve repair. Am J Surg. 2006;191:61-67.

37. Gavron J.P., Clemis J.D. Hypoglossal-facial nerve anastomosis: A review of forty cases caused by facial nerve injuries in the posterior fossa. Laryngoscope. 1984;94(11 Pt 1):1447-1450.

38. Sawamura Y., Abe H. Hypoglossal-facial nerve side-to-end anastomosis for preservation of hypoglossal function: Results of delayed treatment with a new technique. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:203-206.

39. Darrouzet V., Guerin J., Bebear J.P. New technique of side-to-end hypoglossal-facial nerve attachment with translocation of the infratemporal facial nerve. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:27-34.

40. Rebol J., Milojkovic V., Didanovic V. Side-to-end hypoglossal-facial anastomosis via transposition of the intratemporal facial nerve. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006;148:653-657.

41. Godefroy W.P., Malessy M.J., Tromp A.A., et al. Intratemporal facial nerve transfer with direct coaptation to the hypoglossal nerve. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:546-550.