Hypofunction of the adrenal cortex

Adrenal insufficiency

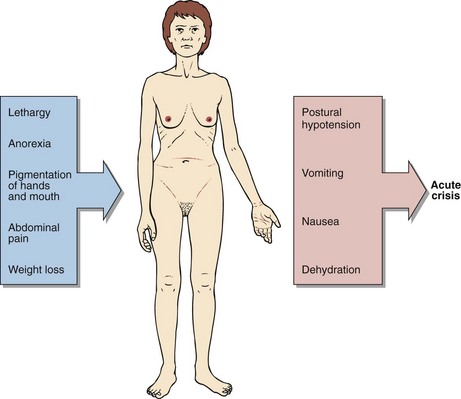

Acute adrenal insufficiency is a rare condition that if unrecognized is potentially fatal. Because of its low incidence it is often overlooked as a possible diagnosis. It is relatively simple to treat once the diagnosis has been made, and patients can lead a normal life. The clinical features of adrenal insufficiency are shown in Figure 48.1.

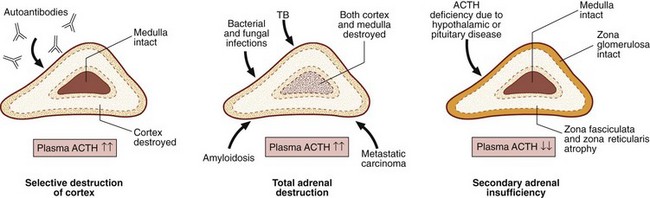

In areas where tuberculosis is endemic, adrenal gland destruction may be due to TB; in developed countries autoimmune disease is now the main cause of primary adrenal failure. Both cortisol and aldosterone production may be affected. Secondary failure to produce cortisol is more common. Frequently, this is due to long-standing suppression and subsequent impairment of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis from therapeutic administration of corticosteroids. The causes of adrenal insufficiency are summarized in Figure 48.2.

Synacthen tests

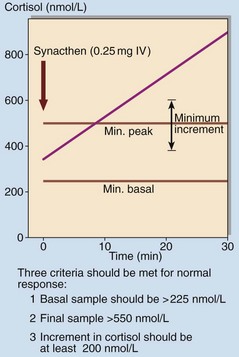

Formal diagnosis or exclusion of adrenal insufficiency requires a short Synacthen test (SST) (see below and p. 83). Synacthen is a synthetic 1-24 analogue of ACTH and is administered intravenously at a dose of 250 µg. Cortisol is measured at 0, 30 and sometimes 60 minutes. The criteria for a normal response are shown in Figure 48.3.

Equivocal or inadequate responses to a SST may require a long Synacthen test (LST) to be performed (see p. 83) in order to establish whether adrenal insufficiency is primary, or secondary to pituitary or hypothalamic disease. Here, depot Synacthen (1 mg) is given intramuscularly daily for 3 days and the SST repeated on the fourth; a normal response makes primary adrenal insufficiency unlikely. Measurement of ACTH may obviate the need for a LST – unequivocally elevated ACTH in the presence of an impaired response to Synacthen confirms the diagnosis of primary adrenal failure.