23 Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Salient features

History

Examination

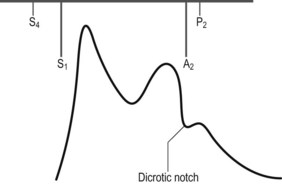

• Carotid pulse is bifid (Fig. 23.1)

• ‘a’ wave in the JVP (see Case 15)

• Double apical impulse (left ventricular heave with a prominent presystolic pulse caused by atrial contraction)

• Pansystolic murmur at the apex caused by mitral regurgitation

• Ejection systolic murmur along the left sternal border (across the outflow tract obstruction); accentuated by standing and Valsalva manoeuvre and softer on squatting (squatting increases LV cavity size and reduces outflow tract obstruction). Remember the Valsalva manoeuvre decreases the duration of murmur of aortic stenosis and increases the murmur of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Advanced-level questions

How would you investigate this patient?

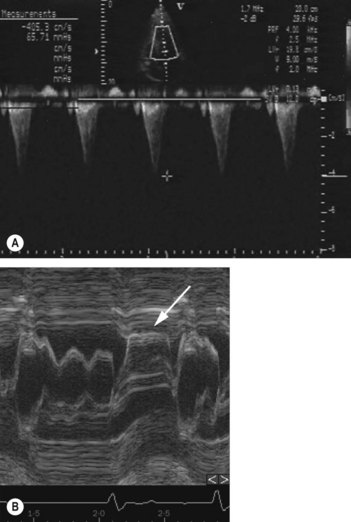

• Echocardiogram is useful for assessing LV structure and function, gradients (Fig. 23.2), valvular regurgitation, and atrial dimensions. Doppler echocardiography shows characteristic high-velocity late peaking or dagger-shaped spectral waveform (Fig. 23.2A). Characteristic findings include systolic anterior motion of mitral valve (SAM), asymmetric hypertrophy (ASH) and mitral regurgitation.

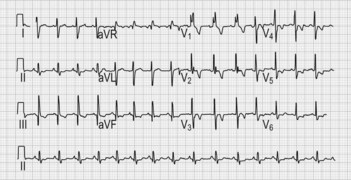

• ECG may be normal (in about 5% of patients) or show abnormalities including left ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation, left axis deviation, right bundle branch block and myocardial disarray (e.g. ST–T wave changes, intraventricular conduction defects, abnormal Q waves); bizarre or abnormal findings in young patients should raise suspicion of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, (especially if family members also affected) (Fig. 23.3).

• Chest radiograph may be normal or show evidence of left or right atrial or left ventricular enlargement.

• Treadmill exercise test is performed when patients have angina (ST segment changes of >2 mm documented in 25% associated with symptoms of angina).

• 48-hour Holter monitoring identifies established atrial fibrillation (in about 10% of patients), paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias (in 30%), non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (in 25%) and ventricular tachycardia (in 25%); ventricular tachycardia is invariably asymptomatic during Holter monitoring but is a most useful risk marker of sudden death in adults; sustained supraventricular arrhythmias often symptomatic and predispose to thromboembolic complications.

• Endomyocardial biopsy possibly necessary to exclude specific heart muscle disorder (amyloid, sarcoid) but has no role in diagnosis because of patchy nature of myofibrillar disarray.

• Cardiac MRI shows patchy areas of hyperenhancement, the extent of which is greatest in patients with risk markers for sudden cardiac death and in those in whom progressive remodelling of the LV can be seen. The predominant site of hypertrophy is usually the 1-o’clock position in the short-axis view at the confluence of anterior septum and anterior wall

• Left heart catheterization is rarely needed to make the diagnosis. In the presence of left ventricular outflow obstruction, the LV-to-aortic late-peaking gradient is seen with characteristic aortic pressure tracing showing a rapid rise and fall followed by a plateau—the ‘spike and dome’ pattern.

How would you manage such a patient?

• Improvement of ventricular function using beta-blocker (propranolol up to 640 mg/day), verapamil, amiodarone and diuretics (N Engl J Med 1997;336:775)

• Prevention of infective endocarditis

• Dual-chamber pacing or DDD pacing is considered by some as the initial procedure in symptomatic patients resistant to treatment with drugs. DDD pacing causes depolarization from the right ventricular apex, resulting in altered motion of the interventricular septum and diminished subaortic gradient

• Implantable-cardiac defibrillators to prevent sudden death

• Prevention of arrhythmias and sudden death by administration of amiodarone (Br Heart J 1985;53:412–16)

• Septal ablation with alcohol or surgery—such as myotomy or myectomy—relieves symptoms but does not alter the natural history of the disease. Mitral valve replacement may be done simultaneously for severe mitral regurgitation

• Counselling of sufferers and relatives is essential and they should be encouraged to contact the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association

• Cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation

• Digoxin and vasodilators should be avoided as they worsen outflow obstruction.

What do you know about the epidemiology of this condition?

• The male to female ratio is equal, although the disease tends to affect younger men and older women.

• In children and adolescents, myocardial hypertrophy often occurs during growth spurts (a negative diagnosis made before adolescent growth does not exclude the condition and re-assessment at a later age is important).

• Myocardial hypertrophy does not ordinarily progress after adolescent growth is completed.

• Sudden death can occur at any age (from childhood over to 90 years), and in subjects who have been asymptomatic all their life. The annual mortality from sudden death is 3 to 5% in adults and at least 6% in children and young adults.

• First-degree relatives of affected patients have a 50% chance of carrying the disease gene; they should be investigated by ECG and two-dimensional echocardiogram. Genetic counselling is therefore important.

What are the risk predictors of sudden death?

| Criteria | Comment | |

|---|---|---|

| History | Exertional or recurrent syncope and presyncope | Risk greatest in children |

| Family history of sudden death, known malignant genotype | Risk related to family size and number of members with sudden cardiac death | |

| Diagnostic evaluation | Severe left ventricular hypertropy | Risk increases with increase in wall thickness |

| Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia | Higher predictive value in children and those with syncope | |

| Abnormal haemodynamic response to exercise (failure to augment systolic BP by at least 20 mmHg) | Less applicable to those >40 years |