Chapter 14 Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

Classification and Definitions

Classification and Definitions

The general classification of hypertensive disorders recommended by the Working Group Report on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy (2000) and adopted by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) in 2002 is listed in Box 14-1. Toxemia should not be used because it represents the entire spectrum of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and may also refer to isolated proteinuria.

BOX 14-1 General Classification of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy.

Based on the National Institutes of Health Working Group Report on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy, 2000.

PREECLAMPSIA/ECLAMPSIA

Preeclampsia is divided into mild and severe forms, depending on the severity of the hypertension, the amount of proteinuria, and the degree to which other organ systems are affected. Box 14-2 lists specific criteria for the diagnosis of severe preeclampsia. If any of the symptoms, signs, or laboratory abnormalities listed in Box 14-2 is present in a woman with preeclampsia, it is very likely that she has severe disease, which is associated with much greater maternal and perinatal morbidity.

BOX 14-2 Criteria for Severe Preeclampsia.

Data from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Practice Bulletin No. 33. Washington, DC, ACOG, 2002.

CHRONIC HYPERTENSION WITH SUPERIMPOSED PREECLAMPSIA

The diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia should be reserved for those women with chronic hypertension who develop new-onset proteinuria (≥0.3 g in a 24-hour collection) after the 20th week of gestation. In pregnant women with preexisting hypertension and proteinuria, the diagnosis of superimposed preeclampsia should be considered if they experience sudden significant increases in blood pressure or proteinuria or any of the other signs and symptoms consistent with severe preeclampsia listed in Box 14-2, including thrombocytopenia or abnormally elevated liver enzymes.

Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

Preeclampsia/Eclampsia

ETIOLOGY

Placental ischemia, or hypoxia, appears to be central to the development of the disease and has been attributed to failure of the cytotrophoblasts to adequately invade the uterine spiral arteries and establish the low-resistance uteroplacental circulation characteristic of normal pregnancy. Placental ischemia could also be due to underlying maternal vascular disease such as might occur in chronic hypertension, or to immunologically mediated placental vascular damage (see Chapter 6). Alternatively, ischemia could be caused by increased metabolic demand in the setting of a multiple gestation or a large singleton fetus.

Evaluation and Management of Preeclampsia

Evaluation and Management of Preeclampsia

The physical examination should focus on the assessment of blood pressure, weight gain, edema, fundal height, and reflexes, and on a qualitative assessment of urinary protein excretion with a dipstick. In addition, findings consistent with severe preeclampsia such as epigastric or right upper quadrant tenderness, uterine tenderness, petechiae due to low platelets, and signs of pulmonary edema should be sought. If there is severe headache or visual symptoms, an ophthalmic examination may be indicated. The initial laboratory studies recommended are outlined in Box 14-3.

BOX 14-3 Initial Laboratory Evaluation on a Patient with Preeclampsia.

SEIZURE PROPHYLAXIS

Table 14-1 outlines the protocols for magnesium administration, and Table 14-2 reviews the relationship among serum magnesium concentrations, clinical response, and signs of toxicity. Therapeutic levels are generally accepted to be in the range of 4.8 to 9.6 mg/dL, but levels should not be allowed to rise above 7 to 8 mg/dL to avoid toxicity. The magnesium ion is excreted exclusively through the kidneys, so careful monitoring of urine output is essential. A magnesium overdose can have severe, even fatal, consequences. Magnesium should be given by a controlled infusion pump with a fail-safe mechanism to prevent errors in administration (i.e., inadvertent bolus infusion). Serial assessments of urine output, deep tendon reflexes, and respirations are important for detecting signs of magnesium toxicity. These clinical assessments should be supplemented with serial measurements of serum magnesium levels every 6 hours and arterial O2 saturation through pulse oximetry. In a patient who has oliguria or a serum creatinine concentration of 1.1 or greater, maintenance infusion rates should be halved and serial magnesium levels measured every 2 hours. Magnesium toxicity can occur even in a patient with apparently normal renal function. Magnesium toxicity is treated by stopping infusion and administering calcium gluconate, 10 mL of a 10% solution, intravenously, and initiating resuscitative measures if necessary.

| Type of Treatment | Intravenous | Intramuscular |

|---|---|---|

| Prophylactic loading | 4 g over 15-20 min | 5 g in each buttock in 100 mL fluid |

| Maintenance | 2 g/hr controlled IV infusion | 5 g/4 hr infusion |

TABLE 14-2 CLINICAL CORRELATES OF SERUM MAGNESIUM SULFATE LEVELS∗

| Clinical Response | Serum Levels (mg/dL) |

|---|---|

| Loss of patellar reflex | 8-12 |

| Warmth and flushing | 9-12 |

| Somnolence | 10-12 |

| Slurred speech | 10-12 |

| Paralysis and respiratory difficulty | 15-17 |

| Cardiac arrest | 30-35 |

ANTIHYPERTENSIVE THERAPY

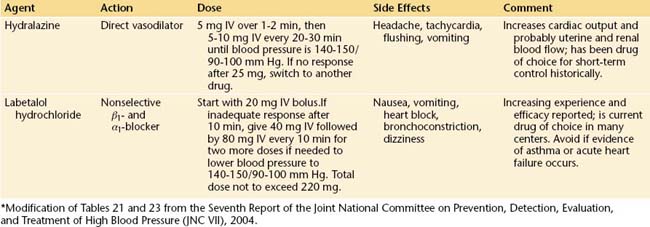

The safest, most efficacious drugs for the acute control of severe hypertension complicating preeclampsia are labetalol and hydralazine. Although hydralazine has theoretical advantages over labetalol in that it is a direct vasodilator and does not induce bronchospasm, rapid bolus infusions are potentially more likely to induce precipitous hypotension. In general, either is acceptable, and their use will be determined by individual circumstances. Table 14-3 details the dosage, duration of action, and potential complications of these two drugs.

MANAGEMENT OF ECLAMPSIA

Eclampsia is a true obstetric emergency, and all physicians involved in the care of pregnant women should be prepared to recognize the occurrence of an eclamptic seizure and begin initial resuscitative and stabilization efforts. The management of these patients should be carried out by a team of physicians and well-trained nurses in an isolated labor room, with minimal noise and not too much light. As with any seizure condition, the initial requirement is to protect the patient from injury, clear the airway, and give oxygen by face mask to relieve hypoxia. Blood pressure and pulse oximetry should be recorded every 10 minutes with the patient in the lateral position. A 16- to 18-gauge IV line should be placed for drawing blood and administering drugs and fluids. An indwelling catheter should be placed in the bladder and laboratory tests obtained as outlined in Box 14-3.

Pharmacologic stabilization consists of preventing recurrent convulsions and controlling hypertension. Randomized, controlled trials have confirmed that magnesium sulfate is the most efficacious drug for preventing recurrent eclamptic seizures and has the best safety profile for the mother and fetus. The administration of IV magnesium sulfate for the treatment of eclamptic seizures is similar to its prophylactic use as outlined in Table 14-1, except that the loading dose is generally increased from 4 to 6 g. The maintenance dose remains 2 g/hour if renal function appears normal. If diazepam (Valium) is used in addition to magnesium sulfate, personnel skilled in intubation should be readily available in case maternal respiratory depression occurs. In general, it is desirable to avoid polypharmacy.

MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC HYPERTENSION

When a woman with chronic hypertension is first seen during the pregnancy, it is important to review previous records to determine whether she has essential hypertension or a secondary cause of high blood pressure. If no previous evaluations have been done, it may be appropriate to rule out some of the more common endocrine, renal, or cardiovascular causes of hypertension. Baseline laboratory tests similar to those outlined in Box 14-3, with the addition of an electrocardiogram (ECG), are useful. The purpose of these tests is to establish a baseline should the patient later develop superimposed preeclampsia as well as to look for evidence of end-organ dysfunction.

A significant increase in hypertension or the development of proteinuria in a previously nonproteinuric patient with chronic hypertension are likely signs of superimposed preeclampsia. The incidence of superimposed preeclampsia varies from 15% to 25%. These patients should undergo repeat laboratory evaluation, as outlined in Box 14-3. Management should follow that outlined for severe preeclampsia.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 29. Washington, DC, ACOG: Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists; 2001.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Diagnosis and management of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 33. Washington, DC, ACOG: Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician-Gynecologists; 2002.

Berg C.J., Chang J., Callaghan W.M., Whitehead S.J. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1991-1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:289-296.

Ilekis J.V., Reddy U.M., Roberts J.M. Preeclampsia—a pressing problem: An executive summary of a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:508-523.

Joint National Committee: Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VII), 2004.

Sibai B.M. Diagnosis, prevention, and management of eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:402-410.

Working Group Report on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. National High Blood Pressure Education Program. NIH Publication No. 00-3029. 2000.

Sequelae and Outcome

Sequelae and Outcome