8 Hypertension

Salient features

Examination

• Comment on Cushingoid facies if present

• Look for radiofemoral delay of coarctation of aorta

• Examine BP in both upper arms (the arm with the higher BP is used for serial follow-up of patients)

• Listen for renal artery bruit of renal artery stenosis and feel for polycystic kidneys.

Look for target organ damage (heart, kidney, nervous system, eyes:

• Palpate the apex for left ventricular hypertrophy

• Look for signs of cardiac failure

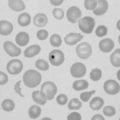

• Examine the fundus for changes of hypertensive retinopathy (see Case 238)

• Tell the examiner that you would like to check urine for protein (renal failure) and sugar (associated diabetes): increases risk of cardiovascular disease.

Diagnosis

This patient has retinopathy (lesion) caused by hypertension, which is probably renovascular (aetiology) as evidenced by the renal artery bruit. She probably has damage to other target organs (functional status).

Questions

How would you record the BP?

Use a device whose accuracy has been validated and one that has been recently calibrated.

Patient should be seated with the arm at the level of the heart. The BP cuff should be appropriate for the size of the arm and the cuff should be deflated at 2 mm/s and the diastolic BP is measured to the nearest 2 mmHg. Diastolic BP is recorded as disappearance of the sounds (phase V).

At least two recordings of BP should be made during at least two subsequent clinic visits where BP is assessed under the best conditions available.

How would you investigate a patient with hypertension in outpatients?

In patients without established cardiovascular disease, assess cardiovascular risk. Investigation should aim to identify diabetes, evidence of hypertensive damage to the heart and kidneys, and secondary causes of hypertension such as kidney disease:

What are the indications for ambulatory blood pressure recording?

• When clinic BP shows unusual variability (it allows detection of patients who are truly hypertensive but office BP measurements are normal—the patients with ‘masked’ hypertension).

• Hypertension is resistant to drug treatment with three or more agents.

• When symptoms suggest that the patient may have hypotension.

What are the NICE guidelines for initiating hypertensive agents?

Aim

The aim for drug therapy in hypertension is to reduce risk of cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure) and mortality:

Initial therapy

The first choice for initial therapy should be:

• lifestyle measures which should be offered initially and continually

• either a calcium channel blocker or a thiazide-type diuretic in hypertensive patients aged ≥55 years or black patients of any age, the first choice for initial therapy. (Black patients are considered to be those of African or Caribbean descent, not mixed-race, Asian or Chinese.)

• an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (or an angiotensin-II receptor antagonist if an ACE inhibitor is not tolerated) in hypertensive patients ≤55 years.

What are the NICE recommendations for follow up of a patient with well controlled blood pressure?

• Annual review of care to monitor BP, provide patients with support and discuss their lifestyle, symptoms and medication.

• Patients may become motivated to make lifestyle changes and want to stop using antihypertensive drugs. If at low cardiovascular risk and with well-controlled BP, these patients should be offered a trial reduction or withdrawal of therapy with appropriate lifestyle guidance and ongoing review.

What the optimal treatment targets?

The optimal treatment targets are systolic BP ≤140 mmHg and diastolic BP ≤85 mmHg. The minimal acceptable level of control is 150/90 mmHg (BMJ 1999;319:630–5).

Why is there increased emphasis on management of systolic blood pressure in those over the age of 50 years?

Although typically guidelines recommend a ‘threshold’ BP for targets (e.g. in 2002 guidelines classify persons with systolic BP of 120–139 mmHg or diastolic BP of 80–89 mmHg as prehypertensive), it is well recognized that the risk is a continuum: for every 20 mmHg increase in systolic BP >115 mmHg, the risk of heart and stroke disease death doubles in patients over the age of 40 and 50 years, respectively. Even a 2–5 mmHg decrease in systolic BP results in significant improvement in mortality.

How would you manage a patient with mild hypertension?

• Diet: weight reduction in obese patients, low cholesterol diets for associated hyperlipidaemia, salt restriction (2–3 g sodium/day), increased consumption of fruit and vegetables

• Regular physical exercise that should be predominantly dynamic (for example brisk walking) rather than isometric (weight lifting).

• Limit alcohol consumption (<14 units per week for women and <21 units/week for men)

Why are beta-blockers no longer recommended as first-line agents in the management of hypertension?

• Beta-blockers are no longer routinely recommended as first-line agents in hypertension because of an increased long-term risk of diabetes, particularly when used with diuretics.

• The CAFE study (Circulation 2006; 113:1213–25) showed that beta-blocker-based treatment was significantly less effective than regimens based on calcium channel blockers at lowering aortic systolic BP and pulse pressure despite identical brachial BP in both treatment groups (pseudo-hypertensive effects).

• In head-to-head clinical trials, beta-blockers were usually less effective than comparator antihypertensive medications at reducing major cardiovascular events, in particular stroke. Atenolol was the beta-blocker used in most of these studies and, in the absence of substantial data on other agents, it is unclear whether this conclusion applies to all beta-blockers. It has been proposed that, in the case of atenolol, insufficient duration of action leaves night-time BP untreated, which is one reason for its lack of efficacy.

However, when hypertension is accompanied by coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, increased sympathetic activity, and arrhythmia, beta-blocker therapy could be beneficial.

What is the role of alpha-blocker-based regimens in the control of blood pressure?

The Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack (ALLHAT) trial showed that an alpha-blocker-based regimen is less effective than a diuretic-based regimen in preventing heart failure (JAMA 2000;283:1967–75). Additionally, there was a marginally significant excess of stroke in the alpha-blocker group. Although poorer BP control might account for the higher risk of stroke, it does not entirely explain the two-fold greater risk of heart failure.

What is role of calcium channel blockers in the treatment of hypertension?

• In the SYST-EUR study, nitrendipine showed a reduction in the risk of stroke in isolated systolic hypertension when compared to diuretics (Lancet 1997;350:757–64).

• In the Swedish Trial in Old Patients with Hypertension-2 (STOP-2) study, there was some evidence that the risks of myocardial infarction and of heart failure were greater with calcium antagonist-based therapy than with ACE inhibitor-based therapy, but there were no clear differences between either of these regimens and a third based on diuretics and beta-blockers (Lancet 1999;354:1751–56). In this study 34–39% of patients withdrew from the three treatment regimens.

• The International Nifedipine GITS Study: Intervention as a Goal in Hypertension Treatment (INSIGHT) trial compared long-acting nifedipine with a diuretic (hydrochlorthizide and amiloride combination) and found that the calcium channel antagonist was as effective as diuretics in preventing overall cardiovascular or cerebrovascular complications (Lancet 2000;356:366–72). There was a marginally significant excess of heart failure with nifedipine-based treatment. Fatal myocardial infarctions were more common in the nifedipine group. There was an 8% excess withdrawal of drug in the nifedipine group because of peripheral oedema, whereas serious adverse events were more frequent in the diuretic group.

• In the Nordic Diltiazem Study (NORDIL) from Sweden, ditliazem was compared with diuretics, beta-blockers or both (Lancet 2000;356;359–65). This study found that diltiazem was as effective as treatment based on diuretics, beta-blockers or both in preventing the primary end-point of all stroke, myocardial infarction and other cardiovascular death. There was a marginally significant lower risk of stroke in the diltiazem group despite a lesser reduction in BP. In this study, 23% of the patients withdrew from the diltiazem-based group and 7% withdrew from diuretic-based and beta-blocker-based therapy.

What is role of ACE inhibitors in hypertension?

• In the HOPE (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation) study, the use of ramipril was associated with reductions of stroke, coronary artery disease and heart failure in both hypertensive and non-hypertensive groups when compared with placebo (N Eng J Med 2000;342:145–53).

• In the Captopril Prevention Project (CAPPP), the risk of stroke was slightly greater with ACE inhibitor-based therapy than with diuretic-based or beta-blocker-based therapy but the higher baseline and follow-up BP among patients assigned the ACE inhibitor regimen may largely or entirely account for the excess risk of stroke (Lancet 1998;353:611–16).

What are the indications for specialist referral?

• Hypertensive emergency: malignant hypertension, impending complications.

• To investigate possible aetiology when evaluation suggests this possibility.

• To evaluate therapeutic problems or failures.

• Special circumstances: unusually variable BP, possible white-coat hypertension, pregnancy (BMJ 1999;319:630–5).

What do you understand by resistant hypertension?

Resistant or refractory hypertension is defined as BP persistently greater than target (i.e. >140/90 mmHg for most patients and >130/80 mmHg in those with diabetes or renal disease) despite therapy with three different antihypertensive medication classes including a diuretic. True resistant hypertension can occur in volume overload, use of contraindicated drugs or exogenous substances and with some associated conditions (e.g. smoking, obesity, pain, excessive alcohol intake). Resistant hypertension can occur secondary to Conn’s adenoma, sleep apnoea, chronic kidney disease.

‘I have also been treating the high cholesterol and then I stopped the medicine because I got my cholesterol down low. And, I had in the past, a little [blood pressure] problem, which I treated and then I got it down…’ (Former US President Clinton, awaiting coronary bypass surgery, calls into Larry King Live from his hospital bed; posted 3 September 2004).