Chapter 17 Hypertension

1 What is considered high blood pressure or hypertension in a child?

2 If a high blood pressure is found incidentally by the triage nurse, what two questions should you ask before you get too worried?

“What size cuff did you use?” Inappropriate cuff size can give spuriously high or low blood pressure readings. They will be falsely elevated if the cuff is too small, and low if the cuff is too big. The width of the cuff bladder should be about 40% of the circumference of the arm measured at the midpoint between the shoulder and the elbow (technically, between the acromion and the olecranon). The cuff should encircle 80–100% of the circumference of the upper arm and be about two-thirds of its length.

“What size cuff did you use?” Inappropriate cuff size can give spuriously high or low blood pressure readings. They will be falsely elevated if the cuff is too small, and low if the cuff is too big. The width of the cuff bladder should be about 40% of the circumference of the arm measured at the midpoint between the shoulder and the elbow (technically, between the acromion and the olecranon). The cuff should encircle 80–100% of the circumference of the upper arm and be about two-thirds of its length.

“Will you please repeat it?” Nonpathologic elevations in blood pressure can be caused by white coats, pain, recent activity, heat, and agitation. Ideally, a child’s blood pressure should be measured after a few minutes of inactivity, as he or she sits calmly in a parent’s lap.

“Will you please repeat it?” Nonpathologic elevations in blood pressure can be caused by white coats, pain, recent activity, heat, and agitation. Ideally, a child’s blood pressure should be measured after a few minutes of inactivity, as he or she sits calmly in a parent’s lap.

3 Which patients need evaluation and treatment in the emergency department (ED), and which patients can follow up with their primary physician?

Workup and treatment: Clearly, patients with hypertensive emergencies should be treated in your department, with the initial focus on ABCs and rapidly establishing IV access. Those children experiencing hypertensive urgencies (i.e., severely elevated blood pressures without evidence of end-organ damage), should be worked up, treated, and admitted for further evaluation.

Workup and treatment: Clearly, patients with hypertensive emergencies should be treated in your department, with the initial focus on ABCs and rapidly establishing IV access. Those children experiencing hypertensive urgencies (i.e., severely elevated blood pressures without evidence of end-organ damage), should be worked up, treated, and admitted for further evaluation.

Workup only: For asymptomatic patients with significantly elevated blood pressure readings, a thorough history and physical examination and some screening laboratory tests should be performed. If there are no abnormalities in this workup, the patient can be discharged with close follow-up.

Workup only: For asymptomatic patients with significantly elevated blood pressure readings, a thorough history and physical examination and some screening laboratory tests should be performed. If there are no abnormalities in this workup, the patient can be discharged with close follow-up.

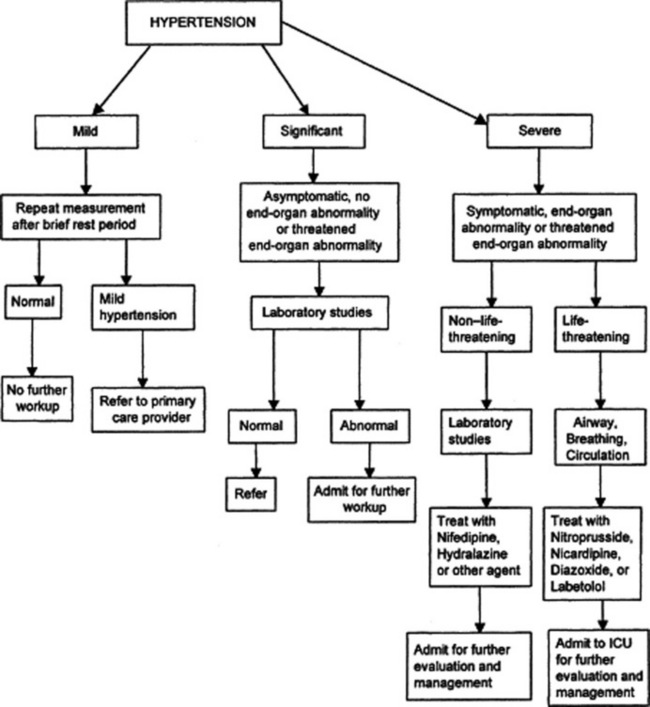

Discharge without workup: Patients being seen for another problem who were incidentally found to have mildly elevated blood pressures and are asymptomatic can be discharged to the care of their primary care physician. Ideally, the doctor should record several readings in a series of visits before confirming the diagnosis of hypertension (Fig. 17-1).

Discharge without workup: Patients being seen for another problem who were incidentally found to have mildly elevated blood pressures and are asymptomatic can be discharged to the care of their primary care physician. Ideally, the doctor should record several readings in a series of visits before confirming the diagnosis of hypertension (Fig. 17-1).

Figure 17-1 Approach to the initial emergency department triage and stabilization of the hypertensive child.

From Linakis JG: Hypertension. In Fleisher GR, Ludwig S, Henretig FM [eds]: Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, 5th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006, with permission.

4 Name the causes of pathologic hypertension. Discuss likely causes in babies, small children, and big children.

Y = Why? Cause unknown—primary hypertension

Y = Why? Cause unknown—primary hypertension

T = Thrombosis (renal artery, particularly if umbilical catheter was used as neonate)

T = Thrombosis (renal artery, particularly if umbilical catheter was used as neonate)

E = Endocrine (congenital adrenal hyperplasia, primary aldosteronism, hyperparathyroidism)

E = Endocrine (congenital adrenal hyperplasia, primary aldosteronism, hyperparathyroidism)

N = Neurologic (increased intracranial, Guillain-Barré syndrome, neurofibromatosis)

N = Neurologic (increased intracranial, Guillain-Barré syndrome, neurofibromatosis)

S = Stenosis (renal artery stenosis or coarctation of the aorta, supravalvular aortic stenosis with Williams syndrome)

S = Stenosis (renal artery stenosis or coarctation of the aorta, supravalvular aortic stenosis with Williams syndrome)

I = Ingestion (cocaine, birth control, steroids, decongestants)

I = Ingestion (cocaine, birth control, steroids, decongestants)

6 What historical questions are important to ask the parent of a hypertensive child?

Does the child have a history of recurrent urinary tract infections? Unexplained fevers? Hematuria? Frequency? Dysuria? Any recent illness? Sore throats?

Does the child have a history of recurrent urinary tract infections? Unexplained fevers? Hematuria? Frequency? Dysuria? Any recent illness? Sore throats?

Did the child have an umbilical artery catheter as a neonate?

Did the child have an umbilical artery catheter as a neonate?

Does he or she have intermittent sweating, flushing, and palpitations?

Does he or she have intermittent sweating, flushing, and palpitations?

Has the child been growing well?

Has the child been growing well?

Has the child suffered any recent head trauma?

Has the child suffered any recent head trauma?

Is there a family history of hypertension, renal disease, or deafness?

Is there a family history of hypertension, renal disease, or deafness?

Has the child ingested anything? Decongestants? Birth control pills? Steroids? Cocaine?

Has the child ingested anything? Decongestants? Birth control pills? Steroids? Cocaine?

7 What physical examination findings are important with a hypertensive child?

General: Dysmorphism (e.g., Williams syndrome), overweight or underweight

General: Dysmorphism (e.g., Williams syndrome), overweight or underweight

Head, ears, eyes, nose, throat: Evidence of head trauma, decreased visual acuity, papilledema, retinal infarcts, abnormal pupillary light reflex

Head, ears, eyes, nose, throat: Evidence of head trauma, decreased visual acuity, papilledema, retinal infarcts, abnormal pupillary light reflex

Lungs: Crackles (evidence of failure)

Lungs: Crackles (evidence of failure)

Heart: Displaced point of maximal impulse, murmurs

Heart: Displaced point of maximal impulse, murmurs

Abdomen: Bruits, hepatomegaly, renal masses

Abdomen: Bruits, hepatomegaly, renal masses

Extremities: Decreased femoral pulses, discrepant four-extremity blood pressures, edema

Extremities: Decreased femoral pulses, discrepant four-extremity blood pressures, edema

Skin: Café-au-lait spots or skin-fold freckling (neurofibromatosis), xanthomas (hyperlipidemia)

Skin: Café-au-lait spots or skin-fold freckling (neurofibromatosis), xanthomas (hyperlipidemia)

9 If a child has a dangerously high blood pressure, should it be lowered to normal as quickly as possible?

10 Discuss which medications you would use to treat hypertension in the ED.

Patients with hypertensive emergencies should be treated in the ED. The medicines you choose will depend on the patient’s current medications, the suspected cause of the hypertension, your comfort with particular medicines, and whether the child’s life is in danger. For non-life-threatening situations, nifedipine and hydralazine are both safe, effective choices. They begin to work about 10 minutes after administration and last for several hours. For immediate results in lowering a dangerously high blood pressure, a nitroprusside infusion will give dose-related effects that will cease within minutes of stopping the infusion. Another alternative is diazoxide, which acts within 3–5 minutes to vasodilate resistance vessels and reduce blood pressure. It is given in frequent small boluses until the desired blood pressure is reached, and lasts between 4 and 12 hours. Labetalol has rapid effects on both α- and β-adrenergic receptors; is somewhat difficult to titrate; and is contraindicated in patients with asthma, heart block, heart failure, and pheochromocytoma. Nicardipine is an effective calcium-channel blocker that acts quickly to reduce peripheral vascular resistance. Because pediatric experience with nicardipine is quite limited, it should be used with extreme caution in children. Figure 17-1 summarizes the approach to the hypertensive pediatric patient in the ED.