Chapter 27 HYPERTENSION

General Discussion

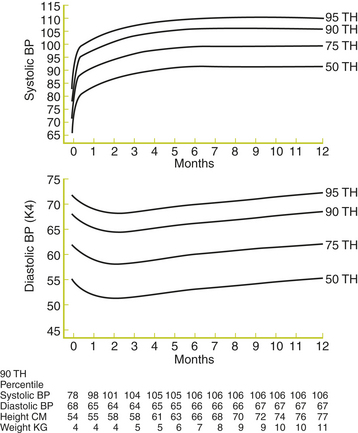

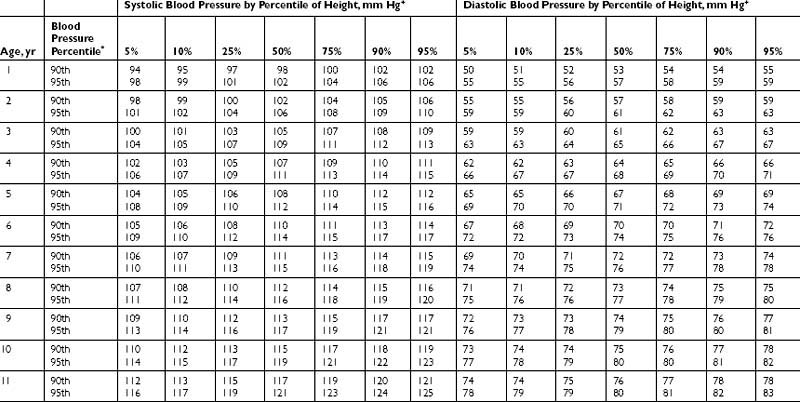

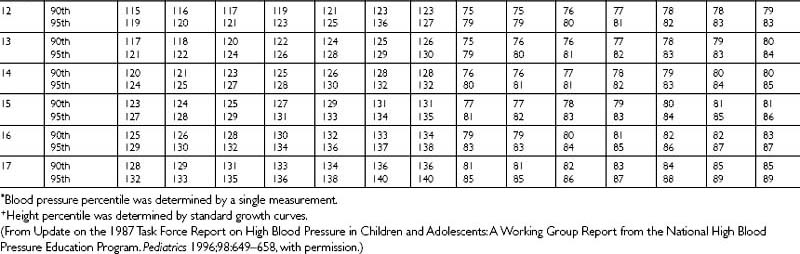

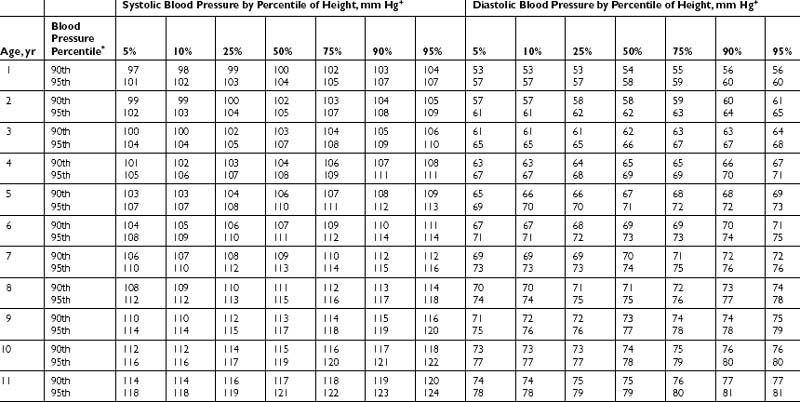

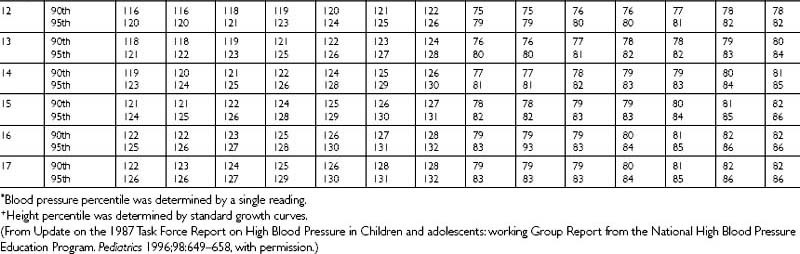

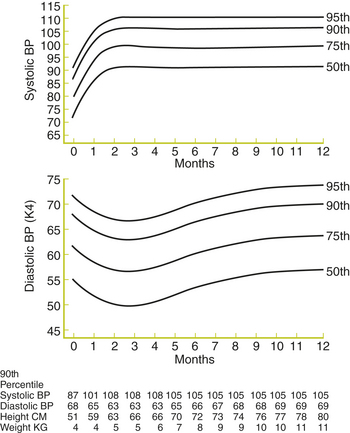

The most commonly used definitions of normal and abnormal BP in childhood come from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group. These definitions are endorsed in the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7). Normal BP is defined as systolic and diastolic BP less than the 90th percentile for age and sex. High-normal BP is defined as average systolic or diastolic BP greater than or equal to the 90th percentile but less than the 95th percentile. Hypertension is defined as average systolic or diastolic readings greater than the 95th percentile based on age, gender, and height percentile (Tables 27-1 and 27-2). At least three abnormal readings, obtained on separate occasions over a period of several weeks, should be obtained before entertaining a diagnosis of hypertension in an individual patient. A separate set of BP percentile curves has been established for infants aged 0 to 12 months (Figures 27-1 and 27-2).

Table 27-1 90th and 95th Percentile Blood Pressures for Boys Aged 1 to 17 Years by Height Percentile

Table 27-2 90th and 95th Percentile Blood Pressures for Girls Aged 1 to 17 Years by Height Percentile.

Figure 27-1 Age-specific percentiles of blood pressure measurements in boys—birth to 12 months of age.

(From Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children. Report of the second task force on blood pressure control in children—1987. Pediatrics 1987;79:1–25, with permission.)

Key Historical Features

Key Physical Findings

Vital signs with systolic and diastolic BPs matched against standards for age, sex, height (see Tables 27-1 through 27-2). Consider measuring the BP in all four extremities regardless of the child’s age to evaluate for coarctation of the aorta.

Vital signs with systolic and diastolic BPs matched against standards for age, sex, height (see Tables 27-1 through 27-2). Consider measuring the BP in all four extremities regardless of the child’s age to evaluate for coarctation of the aorta.

Funduscopic examination to evaluate for microvascular changes, pinpoint hemorrhages, and “cotton wool” spots pinpoint.

Funduscopic examination to evaluate for microvascular changes, pinpoint hemorrhages, and “cotton wool” spots pinpoint.

Head and neck examination to evaluate for moon facies, suggestive of Cushing syndrome; a webbed-neck, suggestive of Turner syndrome; or tonsillar hypertrophy, which may result in obstructive sleep apnea. The thyroid should be palpated for thyromegaly.

Head and neck examination to evaluate for moon facies, suggestive of Cushing syndrome; a webbed-neck, suggestive of Turner syndrome; or tonsillar hypertrophy, which may result in obstructive sleep apnea. The thyroid should be palpated for thyromegaly.

Cardiovascular examination for tachycardia, murmur, friction rub, or apical heave

Cardiovascular examination for tachycardia, murmur, friction rub, or apical heave

Abdominal examination for a palpable mass or abdominal bruit

Abdominal examination for a palpable mass or abdominal bruit

Genital examination for ambiguous genitalia

Genital examination for ambiguous genitalia

Skin examination for flushing or diaphoresis suggestive of pheochromocytoma, café au lait spots suggestive of neurofibromatosis, malar rash suggestive of lupus, or acanthosis nigracans suggestive of diabetes

Skin examination for flushing or diaphoresis suggestive of pheochromocytoma, café au lait spots suggestive of neurofibromatosis, malar rash suggestive of lupus, or acanthosis nigracans suggestive of diabetes

Initial Work-Up

• Electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine

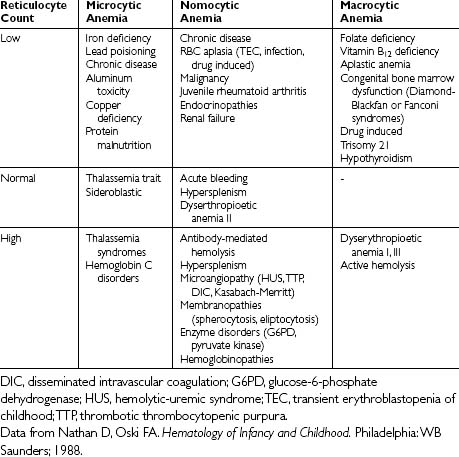

• Complete blood count (CBC) with differential and platelet count

• Echocardiogram in all hypertensive children is suggested by some authorities because left ventricular hypertrophy can be present even in children with mild hypertension.

• Referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist for a thorough retinal examination may be considered in children with hypertension, particularly if the echocardiogram is abnormal.

Additional Work-Up

Specific laboratory tests (as indicated by the history, physical examination, and screening tests):

| 24-hour urine collection for protein excretion and creatinine clearance | If renal disease is suspected or determined by the screening tests |

| Urine and serum catecholamines | If pheochromocytoma is suspected |

| Serum cortisol level | If Cushing’s syndrome is suspected |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroxine (T4), tri-iodothyronine (T3) | If a thyroid disorder is suspected |

| Echocardiogram | If cardiac disease is suspected on the basis of a murmur or other abnormal finding on physical examination. An echocardiogram for all hypertensive children is suggested by some authorities because left ventricular hypertrophy can be present even in children with mild hypertension. |

| Serum 17α-hydroxyprogesterone | If congenital adrenal hyperplasia is suspected |

| Plasma aldosterone | If hyperaldosteronism is suspected |

| Renal ultrasound | If renal disease is suspected to evaluate the contour and texture of the kidneys and to screen for gross renal abnormalities |

| Computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen and pelvis | If an abdominal mass is palpated on physical examination to evaluate for the presence of tumor |

| Plasma rennin and 24-hour urinary sodium excretion | To evaluate for renal artery stenosis |

| Renal ultrasound with Doppler study of renal arteries | To evaluate for renal artery stenosis |

| Captopril challenge test | To evaluate for renal artery stenosis |

| Renal angiography with renal vein renins | To evaluate for renal artery stenosis |

| Magnetic resonance angiography | To evaluate for renal artery stenosis |

| Captopril renal scan | To evaluate for renal artery stenosis |

| Ambulatory BP monitoring | Not yet endorsed by consensus bodies for routine use in children, but may affect the management of childhood hypertension and may predict the presence of secondary hypertension |

| Renal biopsy | To establish a tissue diagnosis in renal disease |

| Angiography | To evaluate for renal artery stenosis |

1. Flynn J.T. Evaluation and management of hypertension in childhood. Progress Pediatr Cardiol. 2001;12:177–188.

2. Lauer R.M., Clarke W.R. Childhood risk factors for adult blood pressure: the Muscatine Study. Pediatrics. 1989;84:633–641.

3. National High Blood Pressure Education Program. Update on the 1987 Task Force Report on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents: a working group report from the National High Blood Pressure Education Program. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on Hypertension Control in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 1996;98:649–658.

4. Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children. Report of the Second Task Force on Blood Pressure Control in Children—1987. Pediatrics. 1987;79:1–25.

5. The Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Hypertension in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):555–576.