Endometrial Hyperplasia and the Differential Diagnosis for Thick Endometrium

Synonyms/Description

Etiology

Ultrasound Findings

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

Figures

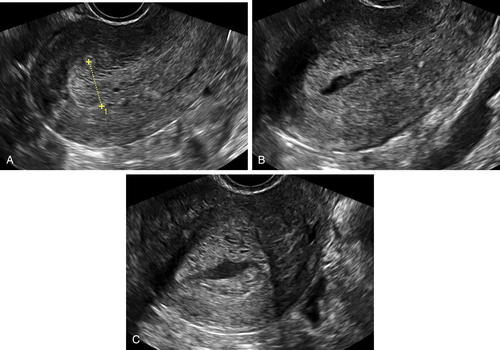

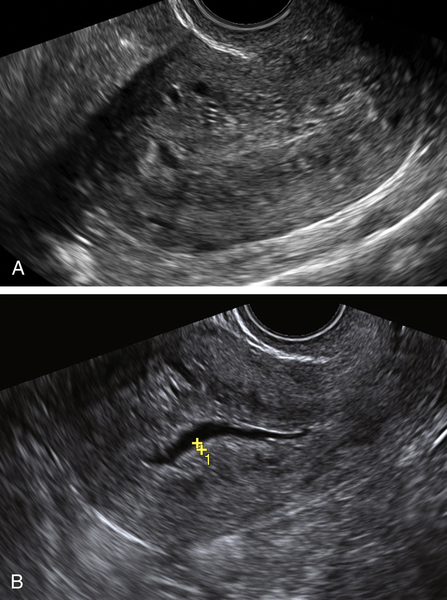

Figure E3-4 Differential diagnosis. A, A thick and irregular endometrium with many cystic spaces obscuring the endometrial-myometrial junction. This patient was on Tamoxifen, and the ultrasound image was not sufficient to evaluate the endometrium. B, The sonohysterogram, which revealed that most of the cystic areas are in the subendometrial region.

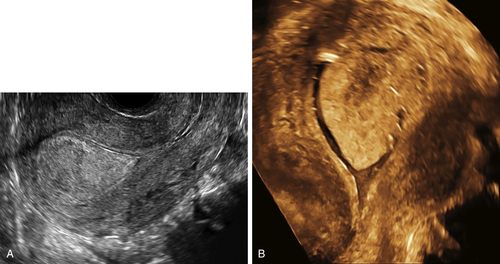

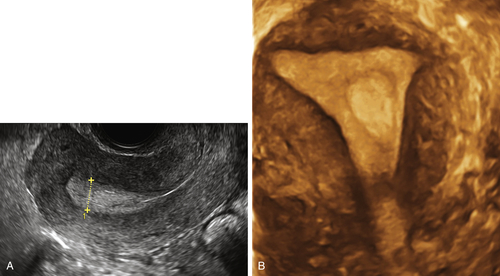

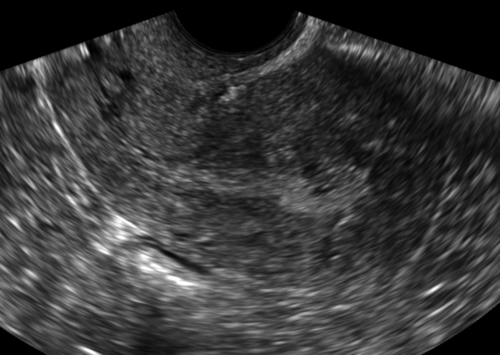

Figure E3-5 Differential diagnosis. Longitudinal view of the endometrium of a postmenopausal patient with bleeding. Note the focal nodular thickening of the endometrium at the fundus (retroverted uterus), with slight irregularity and loss of definition of the endometrial-myometrial junction. The pathology revealed papillary serous adenocarcinoma of the endometrium.

Suggested Reading

Ballard P., Tetlow R., Richmond I., Killick S., Purdie D.W. Errors in the measurement of endometrial depth using transvaginal sonography in postmenopausal women on tamoxifen: random error is reduced using saline instillation sonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;15:321–326.

Goldstein R.B., Bree R.L., Benson C.B., Benacerraf B.R., Bloss J.D., Carlos R., Fleischer A.C., Goldstein S.R., Hunt R.B., Kurman R.J., Kurtz A.B., Laing F.C., Parsons A.K., Smith-Bindman R., Walker J. Evaluation of the woman with postmenopausal bleeding: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound-Sponsored Consensus Conference statement. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:1025–1036.

Goldstein S.R. Modern evaluation of the endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:168–176.

Goldstein S.R. Significance of incidentally thick endometrial echo on transvaginal ultrasound in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2011;18:434–436.

Goldstein S.R. Sonography in postmenopausal bleeding. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:333–336.

Mills A.M., Longacre T.A. Endometrial hyperplasia. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2010;27:199–214.

Montgomery B.E., Daum G.S., Dunton C.J. Endometrial hyperplasia: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59(5):368–378.