Hypernatraemia

Water loss

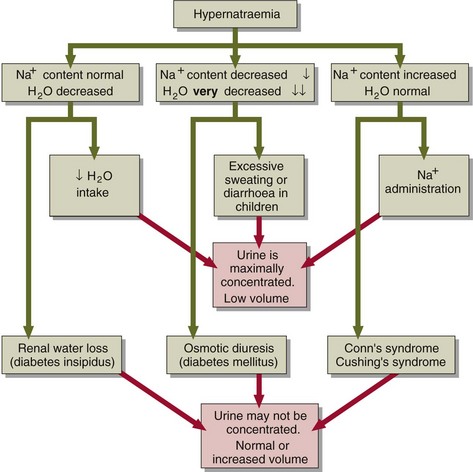

Water and sodium loss can result in hypernatraemia if the water loss exceeds the sodium loss. This can happen in osmotic diuresis, as seen in the patient with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, or due to excessive sweating or diarrhoea, especially in children. However, loss of body fluids because of vomiting or diarrhoea usually results in hyponatraemia (see pp. 16–17).

Sodium gain

The pathophysiological parallel to the administration of sodium is the rare condition of primary hyperaldosteronism (Conn’s syndrome), where there is excessive aldosterone secretion and consequent sodium retention by the renal tubules. Similar findings may be made in the patient with Cushing’s syndrome, where there is excess cortisol production. Cortisol has weak mineralocorticoid activity. However, in both these conditions the serum sodium concentration rarely rises above 150 mmol/L. The mechanisms of hypernatraemia are summarized in Figure 10.1.

Clinical features

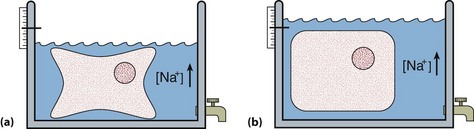

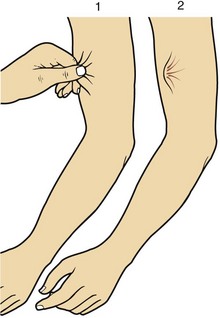

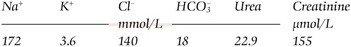

Hypernatraemia may be associated with a decreased, normal or expanded ECF volume (Fig 10.2). The clinical context is all-important. With mild hypernatraemia (sodium <150 mmol/L), if the patient has obvious clinical features of dehydration (Fig 10.3), it is likely that the ECF volume is reduced and that one is dealing with loss of both water and sodium. With more severe hypernatraemia (sodium 150 to 170 mmol/L), pure water loss is likely if the clinical signs of dehydration are mild in relation to the severity of the hypernatraemia. This is because pure water loss is distributed evenly throughout all body compartments (ECF and ICF). (The sodium content of the ECF is unchanged in pure water loss.) With gross hypernatraemia (sodium >180 mmol/L), one should suspect salt poisoning if there is little or no clinical evidence of dehydration; the amount of water that would need to be lost to elevate the sodium to this degree should be clinically obvious, irrespective of whether there has been concomitant sodium loss. Salt gain may present with clinical evidence of overload, such as raised jugular venous pressure or pulmonary oedema.