Hyperfunction of the adrenal cortex

Cortisol excess

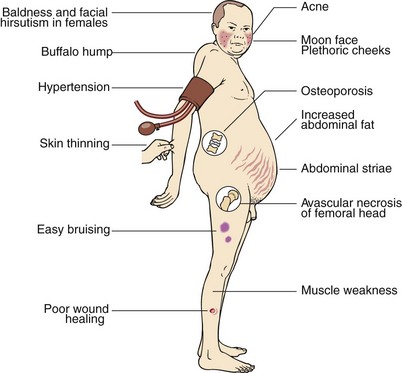

Prolonged exposure of body tissues to cortisol or other glucocorticoids gives rise to the clinical features that collectively are known as Cushing’s syndrome (Fig 49.1), after the American neurosurgeon Harvey Cushing. It most often results from prolonged use of steroid medications (iatrogenic). Much less frequently, it is caused by tumours that secrete either cortisol or ACTH (see below); these can sometimes be very difficult to diagnose.

In any investigation of Cushing’s syndrome the clinician should ask two questions:

‘Does the patient actually have Cushing’s syndrome?’ The possibility that a patient may have Cushing’s syndrome frequently arises because they are obese or hypertensive, conditions frequently encountered in the population at large. Initial investigations will in most cases exclude the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome.

‘Does the patient actually have Cushing’s syndrome?’ The possibility that a patient may have Cushing’s syndrome frequently arises because they are obese or hypertensive, conditions frequently encountered in the population at large. Initial investigations will in most cases exclude the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome.

Once the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome is established, then a second question may be asked: ‘What is the cause of the excess cortisol secretion?’ Tests used in the differential diagnosis are different from those used to confirm the presence of cortisol overproduction.

Once the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome is established, then a second question may be asked: ‘What is the cause of the excess cortisol secretion?’ Tests used in the differential diagnosis are different from those used to confirm the presence of cortisol overproduction.

Determining the cause

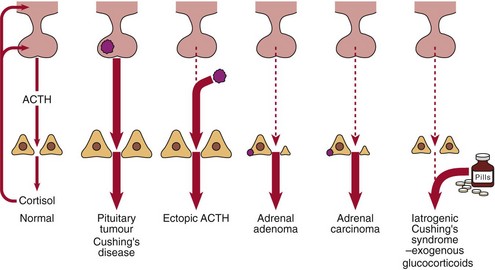

The possible causes of Cushing’s syndrome are illustrated in Figure 49.2. These include:

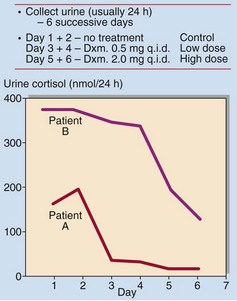

In patients with pituitary-dependent Cushing’s disease the serum or urinary cortisol will be partially suppressed after 2 days of dexamethasone, 2.0 mg q.i.d. (Fig 49.3). Failure to suppress suggests either ectopic ACTH production or the autonomous secretion of cortisol by an adrenal tumour. The presence of hypokalaemia is a tell-tale sign of ectopic ACTH production.

Fig 49.3 The dexamethasone suppression test. Patient A showed a >75% fall in urinary cortisol excretion on the low dose. This is a normal response. Patient B showed some suppression of cortisol secretion on the high dose. This is typical of pituitary-dependent Cushing’s syndrome (Dxm = dexamethasone, q.i.d. = four times daily).

Androgen excess

Adrenocortical tumours, particularly adrenal carcinomas, may produce excess androgens (DHA, androstenedione and testosterone) causing hirsutism and/or virilization in females (see pp. 100–101). This may not necessarily be accompanied by cortisol excess, and signs of Cushing’s syndrome may be absent. Patients with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (p. 95) may also present with signs of increased androgen production.