Chapter 49 Hyoid suspension as the only procedure

1 INTRODUCTION

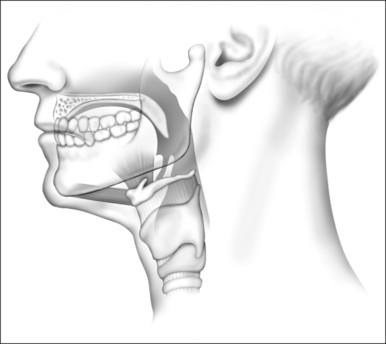

Obstruction of the airway at the retropalatinal and retropharyngeal airway is the key factor in the pathophysiology of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Patient selection is crucial in successful surgery of the upper airway in OSAS. In addition to polysomnography, topical diagnostic work-up is of paramount importance in this regard. We routinely perform polysomnography first, and after that in cases of an Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI) below 30, schedule patients for sedated endoscopy (‘sleep endoscopy’) with midazolam (without an anesthetist present), in those patients in whom surgery is considered. In patients with an AHI > 30, who refuse NCPAP treatment upfront, or in patients who cannot accept NCPAP for whatever reason, sedated endoscopy is performed as well, but by an anesthetist, with propofol. In the study period (March 2000 to June 2004), in the case of mainly or only retrolingual obstruction, as assessed by sleep endoscopy and a low AHI (arbitrarily <15–20, snoring up to mild sleep apnea) we usually started with radio-frequent ablation of the tongue base. In this situation, in the case of mild or moderate OSAS, oral devices were offered as an alternative. In cases of a relatively higher AHI (moderate to severe OSAS), the effect of MRA treatment is less efficacious. In the case of an index of 15–30, and mainly retrolingual obstruction, we performed hyoid suspension (a.k.a. hyoidthyroidpexia) as the only procedure. In higher AHI patients we perform multilevel surgery (hyoid suspension, radiofrequency ablation of the tongue base, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), with/or without genioglossal advancement (see Chapter 17, Multilevel surgery). These patients usually have more severe and multilevel obstruction, which explains the higher AHI.

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.2 UPPER AIRWAY ASSESSMENT

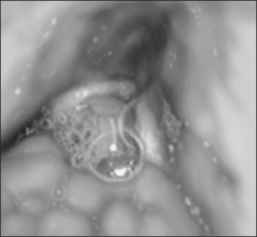

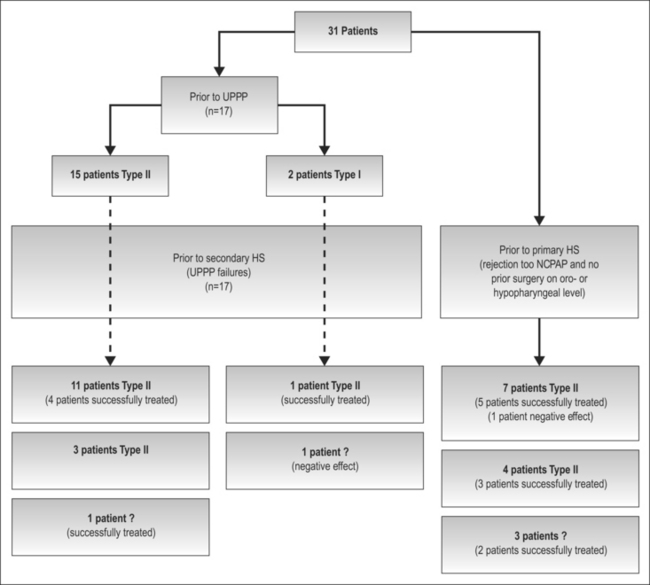

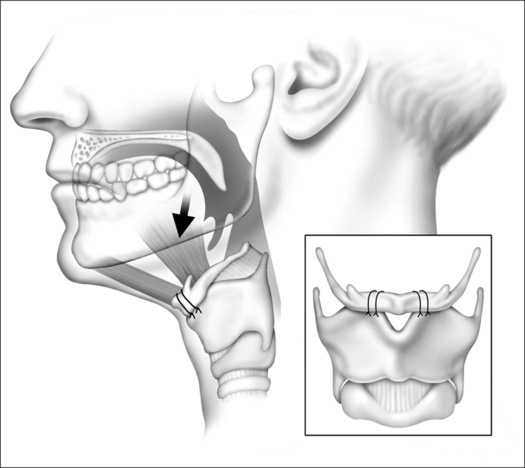

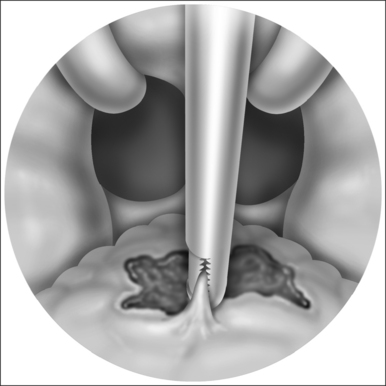

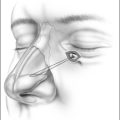

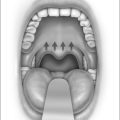

Hyoid suspension was performed in the case of obstruction at the base of tongue (Fig. 49.1), assessed by physical examination and flexible sleep endoscopy. A high suspicion of mainly retropalatal obstruction (large tonsils and long uvula) excluded patients for hyoid suspension. Candidates for surgery were categorized into two groups: those who did not have prior surgery at oro- or hypopharyngeal level (primary hyoid suspension); and those for whom UPPP was inadequate or detrimental (secondary hyoid suspension). In the latter group hyoid suspension was offered as salvage treatment. Multilevel obstruction (Fujita II) occurred in 20 patients; slight obstruction at retropalatal level in nine patients (primary hyoid suspension, n=14) and residual retropalatal obstruction after UPPP in 12 patients (secondary hyoid suspension, n=17). Only four patients who underwent primary hyoid suspension showed simple tongue base obstruction (Fujita III). Prior to UPPP, 15 patients showed multilevel obstruction (Fujita II), with emphasis on thepalatal level; two patients showed retropalatal obstruction only (Fujita I). Sleep endoscopy work-up according to the Fujita classification is shown in Figure 49.2.

3 SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

3.1 HYOIDTHYROIDPEXIA AND POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

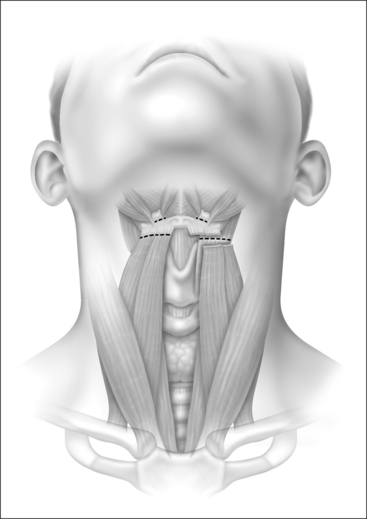

Under general anesthesia, with the head in a slightly extended position, a horizontal incision of approximately 5 cm is made in a relaxed skin tension line at the level between hyoid and thyroid cartilage (Fig. 49.3). Excessive fat tissue is excised, if helpful for better visualization. In the case of a further posterior positioned hyoid, removal of fat is recommended also, since otherwise the anterior placement of the hyoid will result in a somewhat turkey-like neck contour.

5 RESULTS

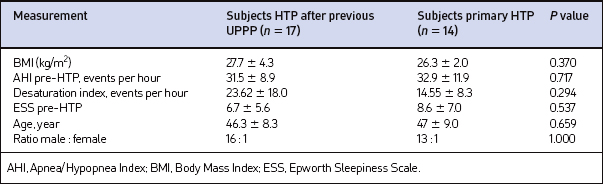

Between March 2000 and June 2004, 31 patients: (29 males and two females) underwent hyoid suspension. Secondary hyoid suspension was performed in 17 patients. Fourteen patients underwent primary hyoid suspension: 12 had difficulties using NCPAP, two refused NCPAP. Patient baseline characteristics are shown in Table 49.1. No differences were found preoperatively for AHI, Body Mass Index (BMI), age, ESS, desaturation indexes and VAS scores. The BMI did not change significantly postoperatively and all polysomnographies were considered valid.

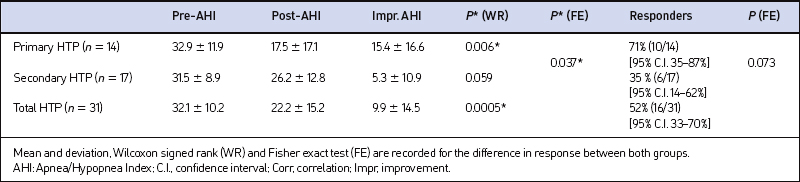

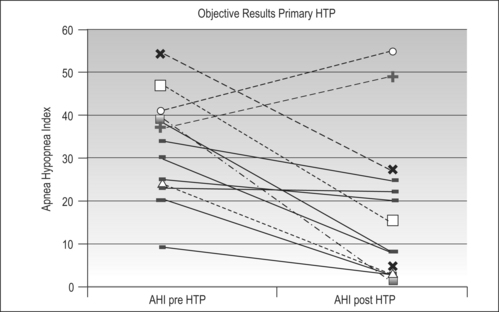

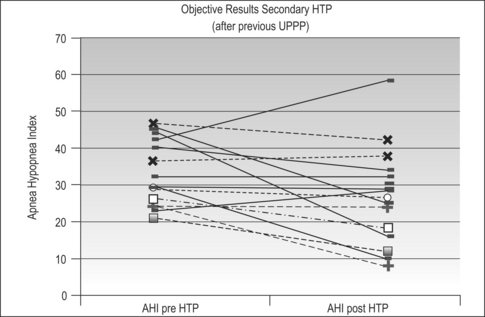

Changes in AHI score are shown in Table 49.2. Twenty-five of the 31 (81%, 95% confidence interval 63–93%) patients showed a decrease in AHI; after secondary hyoid suspension, the mean AHI decreased from 31.5 to 26.2 (P=0.059) (Fig. 49.4) and after primary hyoid suspension the AHI decreased from 32.9 to 17.5 (P=0.0067). The decrease was significantly greater in the primary hyoid suspension group compared to the secondary hyoid suspension group (P=0.037) (Fig. 49.5). In terms of success, 16 of the 31 (52%, 95% confidence interval 33–70%) patients showed a reduction of the AHI of more than 50%, or a post-AHI value below 20 and post-AI below 10. Although almost twice as many patients showed success in the primary hyoid suspension group (35% versus 71%), the difference was not significant (P=0.073).

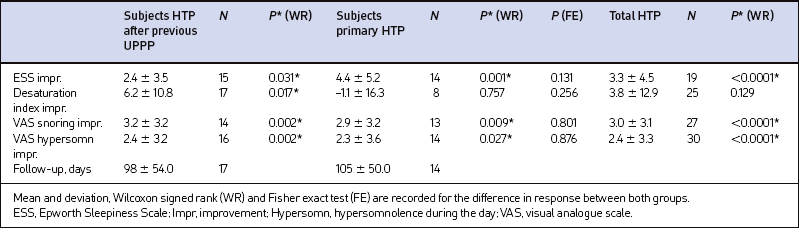

Reduction of snoring in the primary hyoid suspension group (VAS: 8.5 to 5.6, P=0.009) and secondary hyoid suspension group (VAS: 8.8 to 5.6, P=0.002) was significant. No difference in snoring reduction was observed between both groups (P=0.80). VAS scores for hypersomnolence showed a significant decrease from 6.6 to 4.3 (P=0.027) and 5.8 to 3.4 (P=0.002) after primary and secondary hyoid suspension respectively; again, no difference was found between the groups (P=0.88). All patients experienced less morbidity after hyoid suspension than after UPPP. The VAS pain score after UPPP (with paracetamol 1000 mg four times daily) was 7.0; after hyoid suspension patients’ marked (without painkiller) 2.2. ESS scores significantly dropped for both primary and secondaryhyoid suspension (P=0.001 and P=0.031 respectively). No difference was found between the two groups (P=0.13). Statistical details are shown in Table 49.3.

No significant correlations between ESS scores and AHI indexes pre- and postoperatively, ESS scores and VAS scores for hypersomnolence preoperatively and AHI indexes and VAS scores for hypersomnolence preoperatively were seen. However, a positive correlation between postoperative VAS scores for hypersomnolence and AHI indexes as well as ESS scores postoperatively (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.48, P=0.006 and 0.52, P=0.004) was detected.

7 DISCUSSION

Short-term experiences with hyoid suspension only, especially as primary treatment, in this small series of patients with retrolingual obstruction as assessed by sedated endoscopy, with moderate to severe OSAS, are favourable.Our results show that hyoid suspension only can be efficacious: 71% of the patients did not need further treat-ment. Only four patients were not successfully treated. Alternative treatment was offered to hyoid suspension failures, including a new attempt with NCPAP treatmentor oral device and revision surgery of relative palatal stenosis after UPPP. A floppy epiglottis caused airway obstruction at hypopharyngeal level in two other cases; these patients were considered non-responders. One patient underwent partial epiglottectomy. Clinical improvementin those patients, in terms of reduced snoring andimprovement in general well-being, was such that further therapy was not regarded as necessary by both patient and physician.

1. Bowden MT, Kezirian EJ, Utley D, Goode RL. Outcomes of hyoid suspension for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:440-445.

2. Den Herder C, Schmeck J, Appelboom DJ, de Vries N. Risks of general anaesthesia in people with obstructive sleep apnoea. BMJ. 2004;329:955-959.

3. Den Herder C, van Tinteren H, de Vries N. Hyoidthyroidpexia: a surgical treatment for sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(4):740-745.

4. Den Herder C, van Tinteren H, de Vries N. Sleep endoscopy versus modified Mallampati score in sleep apnea and snoring. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(4):735-739.

5. Den Herder C, van Tinteren H, Kox D, de Vries N. Bipolar radiofrequency induced thermotherapy of the tongue base: its complications, acceptance and effectiveness under local anesthesia. Eur Arch Otolaryngol 2006;263:1031–40.

6. Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, Roth T. Surgical correction of anatomic abnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923-934.

7. Hessel NS, de Vries N. Diagnostic work-up of socially unacceptable snoring II Sleep endoscopy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259:158-161.

8. Hessel NS, Laman M, van Ammers VCPJ, de Vries N. Diagnostic work-up of socially unacceptable snoring. I History or sleep registration. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259:154-157.

9. Kezirian E, Goldberg AN. Hypopharyngeal surgery in obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:206-213.

10. Schmidt-Nowara W, Lowe A, Wiegand L, Cartwright R, Perez-Guerra F, Menn S. Oral appliances for the treatment of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep. 1995;18:501-510.

11. Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:156-177.

12. Stuck B, Neff W, Hörmann K, et al. Anatomic changes after hyoid suspension for obstructive sleep apnea: a MRI study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:397-402.