Chapter 51 Hyo-mandibular suspension and hyoid expansion for obstructive sleep apnea

1 INTRODUCTION

Upper airway obstruction results from excess and/or collapse of soft tissue in the soft palate, tonsillar pillars, tongue, tongue base, and hypopharyngeal walls. Specific anatomic risk factors predisposing to obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) include long soft palate, shallow palatal arches, large tongue base, narrowmandibular arches, and mandibular hypoplasia.1 Othergeneral anatomic factors often associated with OSAHS include obesity, large Body Mass Index (BMI), shortened thick neck, anterior larynx location, enlarged tonsils and/or adenoids, lingual tonsils, thickened pharyngeal walls, elongated uvula, redundant soft palate, large tonguevolume, deviated nasal septum, turbinate hypertrophy, and redundant or folded epiglottis.2 Cephalometric studies employing computed tomography (CT) have correlated increased OSAHS severity with increased BMI, larger tongue and soft palate volumes, and decreasedairway space.3 Diagnostically, Fujita employed endoscopy with the Mueller maneuver (reverse Valsalva) to identify sites of obstruction in the nasopharynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx.4 Three general profile types were identified based on the predominant areas of obstruction:Type I – retropalatal/velopharyngeal; Type II – retropalatal/velopharyngeal and hypopharyngeal; and Type III –hypopharyngeal. Catheter pressure transducers employed in OSA sleep studies have shown that upper airway collapse occurred at the velopharyngeal/retropalatal level and the hypopharyngeal/postlingual level in comparable frequencies.5

2 OPERATIVE PROCEDURES

2.1 HYO-MANDIBULAR SUSPENSION

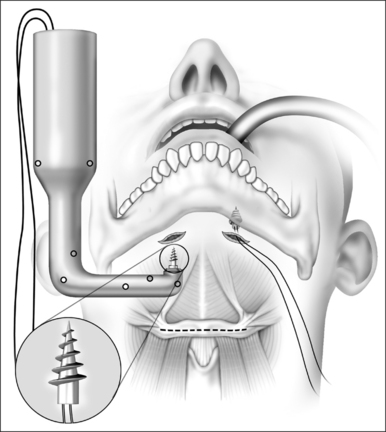

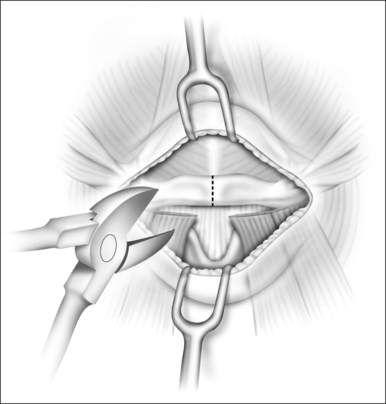

The anterior neck is prepped and draped. The anterior mandible, hyoid and the thyroid cartilages are then outlined with a skin marker with the neck slightly extended. Lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 is injected into the planned incision sites. Two 0.5 cm incisions are made under the chin off the midline and using blunt dissection, the soft tissues overlying the mandible are cleaned. After insertion of the first screw using the Repose device (Influent, Concord, NH), the screw inserter is loaded with a new spare screw and the inserter is positioned perpendicular to the mandible, firm pressure applied and the screw is inserted into the inferior edge of the mandible. A loop of #1 polypropylene suture is already preloaded to the screw by the manufacturer (Fig. 51.1).

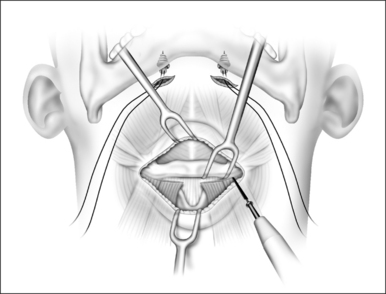

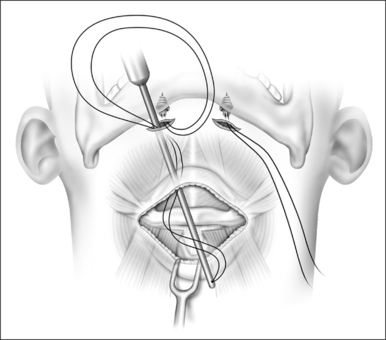

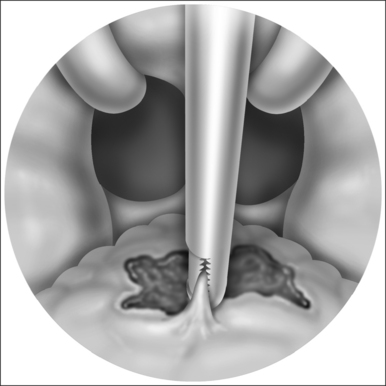

A second horizontal incision is made over the body of the hyoid measuring 5–6 cm. Subcutaneous fatty adipose tissue can be dissected and removed. Electrocautery is used to separate the infrahyoid muscles from the body of the hyoid bone. A single bone hook is placed to retract and stabilize the hyoid during the dissection. The sternohyoid and thyrohyoid muscles are detached from the body of the hyoid between the lesser cornuae (Fig. 51.2). Careful dissection around the body of the hyoid eliminates risk of injury to the neurovascular structures. Careful dissection and good hemostasis are mandatory to avoid injury to the pre-epiglottic fat pad. The suture passer is then loaded with the polypropylene suture and tunneled at the subplatysma layer from the mandibular incisions into the lower (hyoid) incision (Fig. 51.3). The suture passer is then removed. One free end of the polypropylene suture is then loaded into a Mayo needle and is passed through the suprahyoid muscles, catching a full thickness bite of the tissue.

2.2 HYOID DISTRACTION AND EXPANSION

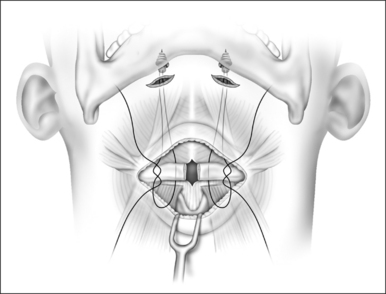

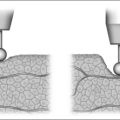

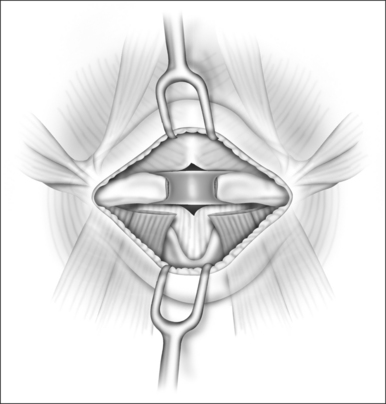

When the hypopharyngeal airway needs to be enlarged in a lateral direction, as determined by preoperative fiberoptic endoscopy, the hyoid bone is then divided in the midline (hyoid distraction) (Fig. 51.4). Following the division of the hyoid bone the polypropylene suture is passed around both sides of the divided edges in a figure of eight configuration (Fig. 51.5). The distracted hyoid segments are then prepared for suspension toward the mandible. In order to maintain stability of the two hyoid segments an absorbable or non-absorbable rigid or semirigid implant can be placed to keep the two ends of the divided hyoid in expansion (hyoid expansion) (“>Fig. 51.6).

Fig. 51.6 Hyoid spacer between the two cut ends of the bone, using non-absorbable graft. Hyoid expansion.

All patients were admitted for close observation overnight. Perioperative and postoperative care includes steroids, intravenous antibiotics, anti-reflux medications, humidified oxygen, intravenous fluids, nasal trumpet, and pulse oximetry monitoring.

4 DISCUSSION

The advantages of the hyoid expansion and suspension are multi-fold. The splitting of the hyoid allows for potential lateral widening of the hypopharyngeal airway. Division of the infrahyoid musculature allows partial separation of the larynx from the hyoid and tongue base. This incomplete laryngeal drop can keep the inferior pulling force of intrathoracic structures from the hypopharyngeal structures separate. The negative pressures that occur during the inspiration phase of respiration in an OSA patient can significantly contribute to further collapsing the flaccid structures of the upper airway.

Potential complications of hyoid suspension and expansion include airway obstruction, prolonged odynophagia, speech problems, neck hematoma, wound infection and intense cervical pain. Our experience, however, has shown very few problems. Pain and dysphagia/odynophagia are the most common complaints, but have all resolved in reasonable time. Patients with prolonged dysphagia/odynophagia may benefit from instructions on a modified supraglottic swallow (tongue push and elevation with throat clearing) as mentioned by Woodson and Fujita.6,7 It is important to note that there were no airway or bleeding problems in the perioperative period. There were no suture or equipment problems either.

1. Rojewski TE, Schuller DE, Clarke RW, et al. Video-endoscopic determination of the mechanisms of obstruction in obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:127-131.

2. Chervin RD, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea and related disorders. Neurol Clin. 1996;14(3):583-609.

3. Lowe AA, Fleetham JA, Adachi S, et al. Cephalometric and computed tomographic predictors of obstructive sleep apnea severity. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1995;107:589-595.

4. Fujita S. Pharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea and snoring. In: Fairbanks DNF, et al, editors. Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. New York: Raven Press; 1987:101-128.

5. Chaban R, Cole P, Hoffstein V. Site of upper airway obstruction in patients with idiopathic obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:641-647.

6. Fujita S, Woodson BT, Clark J, et al. Laser midline glossectomy as a treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:805-809.

7. Woodson BT, Fujita S. Clinical experiences with lingualplasty as part of the treatment of severe obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:40-48.

1. Aboussouan LS, Golish JA, Dinner DS, et al. Limitations and promise in the diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Respir Med. 1997;91:181-191.

2. Chaban R, Cole P, Hoffstein V. Site of upper airway obstruction in patients with idiopathic obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:641-647.

3. Chervin RD, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea and related disorders. Neurol Clin. 1996;14(3):583-609.

4. Crumley RL, Stein M, Gamsu G, et al. Determination of obstructive site in obstructive sleep apnea. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:301-308.

5. DeRowe, A, Gunther, E, Fibbi, A, et al. Tongue-base suspension with a soft tissue-to-bone anchor for obstructive sleep apnea: preliminary clinical results of a new minimally invasive technique. otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;122:100–3.

7. Fujita S. Pharyngeal surgery for obstructive sleep apnea and snoring. In: Fairbanks DNF, et al, editors. Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. New York: Raven Press,; 1987:101-128.

6. Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, et al. Surgical correction of anatomic abnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923-934.

8. Haraldsson P, Carenfelt C, Lysdahl M, et al. Long-term effect of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty on driving performance. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:90-94.

9. Kimmelam CP, Levine SB, Shore ET, et al. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty: a comparison of two techniques. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:1488-1490.

11. Lowe AA, Gionhaku N, Takeuchi K, et al. Three-dimensional CT reconstructions of tongue and airway in adult subjects with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1986;90:364-374.

10. Lowe AA, Fleetham JA, Adachi S, et al. Cephalometric and computed tomographic predictors of obstructive sleep apnea severity. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1995;107:589-595.

12. National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research. A report of the National Commission on Sleep Disorders Research. Wake up America: A National Sleep Alert, vol 2. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office 1995; p. 10.

13. Partinen M, Jamieson A, Guilleminault C. Long-term outcome for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome patients: mortality. Chest. 1988;94:1200-1204.

14. Piccirillo JF, Gates GA, White DL, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea treatment outcomes pilot study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118(6):833-844.

15. Pollack CP, Chervin RD, Weitzman ED. Symptomatic improvement in 34 of 40 cases of severe hypersomnia–sleep apnea syndrome treated by tracheoplasty. Sleep Res. 1982;11:163-166.

16. Rapoport DM, Garay SM, Goldring RM. Nasal CPAP in obstructive sleep apnea: mechanisms of action. Bull Eur Physiopath Resp. 1983;19:616-620.

17. Riley R, Guilleminault C, Powell N, et al. Palatopharyngoplasty failure cephalometric roentgenograms and obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93:240-250.

18. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C, et al. Maxillary mandibular and hyoid advancement: an alternative to tracheostomy in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:584-588.

19. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Inferior sagittal osteotomy of the mandible with hyoid myotomy–suspension: a new procedure for obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;94:589-593.

21. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Maxillofacial surgery and obstructive sleep apnea: a review of 80 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;101:353-361.

20. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Maxillary mandibular and hyoid advancement for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 40 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:20-26.

23. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108:117-125.

24. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a surgical protocol for dynamic upper airway reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:742-747.

22. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea and the hyoid: a revised surgical procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:717-721.

25. Rojewski TE, Schuller DE, Clarke RW, et al. Video-endoscopic determination of the mechanisms of obstruction in obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:127-131.

26. Rubin A-HE, Eliaschar I, Joachim Z, et al. Effects of nasal surgery and tonsillectomy on sleep apnea. Bull Eur Physiopath Resp. 1983;19:612-615.

28. Shepard JW, Thawley SE. Localization of upper airway collapse during sleep in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:1350-1355.

29. Sher AE, Thorpy AJ, Shprintzen RJ, et al. Predictive value of Mueller maneuver in selection of patients for uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:1483-1487.

27. Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:(2):156-177.

30. Terris DJ, Wang MZ. Laser-assisted uvulopalatoplasty in mild obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:718-720.

31. Waite WP, Wooten V, Lachner J, et al. Maxillomandibular advancement surgery in 23 patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:1256-1261.

32. Woodson BT, Wooten MR. Comparison of upper-airway evaluations during wakefulness and sleep. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:821-828.

33. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, et al. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230-1235.

34. Zorick F, Roehrs T, Conway W, et al. Effects of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty on the daytime sleepiness associated with sleep apnea syndrome. Bull Eur Physiopath Resp. 1983;19:600-603.