Chapter 40 Hydrotherapy*

History

History

Hippocrates used hydrotherapy extensively around 400 BC, and his writings concerning baths contain some of the earliest dictums on the therapeutic uses of water1:

In general it suits better with cases of pneumonia than in ardent fevers; for the bath soothes the pain in the side, chest and back; cuts the sputum, promotes expectoration, improves the respiration, and allays lassitude; for it soothes the joints and outer skin, and is diuretic, removes heaviness of the head, and moistens the nose.

Priessnitz’s philosophy of water cure was brought to the United States in the mid-nineteenth century. Joel Shew, a medical doctor from New York, studied with Priessnitz and returned to the United States to start a hydropathy institute based on his teachings. An associate of Shew’s, Russell Trall, MD, started his own hydrotherapy institute in Manhattan in the 1850s and later published the Hydropathic Encyclopedia. John Harvey Kellogg attended Trall’s institute, and in 1900 published Rational Hydrotherapy,2 in which he considered the physiologic and therapeutic effects of water, along with an extensive discussion of hydrotherapeutic techniques.

Benedict Lust, considered to be the father of naturopathy, was successfully treated by Father Kneipp and was charged with introducing the water cure to the United States. Lust successfully combined water cure with other nature cure modalities, establishing the foundation of naturopathic medicine. Henry Lindlahr, a wealthy U.S. banker suffering from diabetes, visited Kneipp after being told by his physicians that there was nothing they could do for him. He was put on a strict diet and daily regimen of cold water treatments. Once cured, he returned to the United States, completed medical training and opened a sanitarium in Chicago in 1906. He believed the vis medicatrix naturae was the true physician and wrote Nature Cure,3 the definitive guide to the philosophy and practice of nature cure medicine.

Physiologic Effects of Water

Physiologic Effects of Water

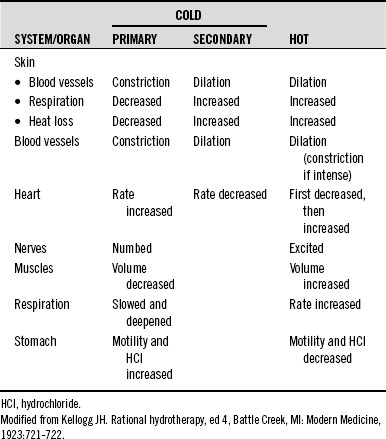

In general, hot relaxes and sedates, whereas cold stimulates, invigorates, and tonifies. However, very hot can stimulate and also be destructive, whereas prolonged cold can be depressive and destructive. A comparison of the effects of hot and cold on several body systems is given in Table 40-1.

Principles of Blood Movement with Hydrotherapy

Revulsive Effect

The revulsive effect provides a means of increasing the rate of BF through an organ or area of the body and is most effectively accomplished using contrast hydrotherapy: alternating hot and cold in the form of compresses, baths, showers, sprays, etc. Local contrast applications produce marked stimulation of local circulation. A 30-minute local contrast bath produces a 95% increase in local BF when the lower extremities alone are immersed. When all four extremities are immersed at the same time, there is a 100% increase in BF in the upper extremities and a 70% increase in the lower extremities.4

Several studies have researched the optimal treatment times for revulsive effects. Woodmansey et al5 found 6 minutes of hot application and 4 minutes of cold to be optimal for the British subjects he studied. Krussen6 found 4 minutes of hot and 1 minute of cold to be the best treatment protocol. Moor7 stated that 3 minutes of hot followed by 30 to 60 seconds of cold provided satisfactory clinical results. These variations create an inference that, due to variations in patients and locales, it is best for practitioners to determine their own ideals, based on their own observations of clinical results. Most importantly, the cold application needs to be long enough to produce vasoconstriction, which can occur in as short a period as 20 seconds. Additionally, the course of treatment should always end on cold to discourage congestion in the area.

Spinal Reflex Effect

A sufficiently intense local application of hot or cold not only affects the immediate skin area but also causes remote physiologic changes, mediated through spinal reflex arcs (see Moor7), thus providing a means of affecting a distant area of the body through a local application. These effects have been carefully observed over many years and have led to a mapping that correlates each surface area with a corresponding internal area and/or organ. Most texts on hydrotherapy contain such a diagram.2,7

Hewlett,8 Stewart,9 and Briscoe10 all noted changes in BF in the opposite arm and hand when one arm and hand were placed in hot or cold water. Poulton11 demonstrated that esophageal function could be influenced by irritation of the skin over the sternum. Bing and Tobiassen12 showed reflex relationships between the skin of the abdominal wall and the colon. They also demonstrated a reflex relationship between the lungs and the skin of the chest wall.

Fisher and Solomon13 stated: “externally applied heat not only decreases intestinal blood flow, but also diminishes intestinal motility and decreases acid secretion in the stomach, while cold has the opposite effect.” This is an example of a contrary effect, in which the reflex effect is the opposite of that observed in the local reflex skin area (i.e., local heat increases BF to the local skin, but decreases BF to the reflex organs).

Tables 40-2 to 40-4 show some of the observed reflex effects of hydrotherapeutic procedures.7

| APPLICATION LOCATION | EFFECT |

|---|---|

| One extremity | Vasodilation in contralateral extremity |

| Abdominal wall | Decreased intestinal blood flow, intestinal motility, and acid secretion |

| Pelvis | Relaxes pelvic muscles, dilates blood vessels, and increases menstrual flow |

| Precordium | Increases heart rate, decreases its force, and lowers blood pressure |

| Chest | Promotes ease of respiration and expectoration |

| Trunk | Relaxes ureters or bile ducts and relieves renal or gallbladder colic |

| Over kidney | Increases production of urine |

TABLE 40-3 Reflex Effects of Prolonged Cold

| APPLICATION LOCATION | EFFECT |

|---|---|

| Trunk of an artery | Contraction of the artery and its branches |

| Nose, back of neck | Contraction of the blood vessels of the feet and hands and nasal mucosa |

| Precordium (ice bag) | Slows the heart rate and increases its stroke volume |

| Abdomen | Increases intestinal blood flow, intestinal motility, and acid secretion |

| Pelvic area | Stimulates muscles of the pelvic organs |

| Thyroid gland | Contracts its blood vessels and decreases its function |

| Hands and scalp | Contraction of brain–blood vessels |

| Acutely inflamed areas | Vasoconstriction and relief of painful joints or bursae |

TABLE 40-4 Reflex Effects of Short Cold

| APPLICATION LOCATION | EFFECT |

|---|---|

| Local application of intense cold as brief as 30 s | General peripheral vasoconstriction |

| Face, hands, and head | Increase in mental alertness and activity |

| Precordial area | Increase in heart rate and stroke volume |

| Chest, with friction or percussion | Initial increase in respiratory rate, then slower, deeper respiration |

Collateral Circulation Effect

The collateral circulation effect may be considered a special case of the derivative effect.2 In general use, the derivative effect involves blood volume changes from one area of the body to another, as previously discussed. The collateral circulation effect, in contrast, more specifically considers the local circulatory effects on deep (rather than superficial) collateral branches of the same artery.

Considering the circulatory patterns of a large body part, such as the thigh, it is clear that both superficial and deep areas are supplied by the same artery. A hot application to this area dilates the surface vessels, drawing blood to the superficial areas and concurrently decreasing the BF to the deep areas. A cold application causes the opposite effect. Local compresses and fomentations are the most commonly used techniques to affect collateral circulatory changes.

Arterial Trunk Reflex

The arterial trunk reflex effect is a special case of the general reflex effect.2 Prolonged cold applied over the trunk of an artery produces contraction of the artery and its branches distal to the application. Prolonged hot applications have the opposite effect, producing dilatation in the distal arterial bed. For example, prolonged cold application over the femoral artery in the groin will decrease BF in a foot or ankle with an acute injury involving either internal or external hemorrhage. After the acute phase, prolonged hot applications can be used to increase circulation and speed healing of the injured part.

Local and Systemic Effects of Cold Applications

Cold applications are often prescribed for the relief of pain. Saeki5 found cold, but not hot, applications to be useful in the relief of prickly pain sensations experimentally induced in study subjects. Pain sensations were measured on the visual analog scale, and skin BF and skin conductance levels (SCL) were also measured. Cold applications decreased pain, BF, and SCL, whereas hot applications increased pain, BF, and SCL.

In 2002, a small (19 patients) study entitled “To Evaluate the Effect of Local Application of Ice on Duration and Severity of Acute Gouty Arthritis” was published.14 Treatment and control groups both received oral prednisone 30 mg tapered to 0 mg over 6 days and colchicine 0.6 mg daily. The treatment group received daily ice applications, whereas the control group did not. After 7 days, treatment group participants had a significant reduction in pain compared with the control group.

Cold water is very effective in lowering body temperature caused by fever due to illness or increased core temperature from exposure or exercise. Cold sponging has often been recommended for the reduction of fevers in children. Two articles published in 199715,16 compared the use of sponging to oral antipyretics. Both studies concluded that sponging was more effective than medication in the first 30 minutes, but after that, the antipyretic medications were more effective. This makes sense, because it takes time for the medications to be absorbed and circulate in the body, whereas the body responds immediately to the application of water to the skin. One of the primary precepts of naturopathic medicine is to work with the vis medicatrix naturae, and fever is one of the body’s responses to acute illness, assisting in the healing process. Lindlahr stated, “every so called acute disease is the result of a cleansing and healing effort of nature.”3 The benefit of sponging to reduce fever versus use of antipyretic medication is the ability to better control how much we reduce the fever, if at all.

Local and Systemic Effects of Hot Applications

Water at 98° F or above is generally perceived as hot, and water higher than 104° F is considered very hot. At 120° F, an immersion bath becomes unendurable, although small areas of the body, such as the hand, may be conditioned to endure a temperature of 10° to 15° higher for short periods. The mucus membranes, unlike the skin, may endure temperatures as high as 135° F, which accounts for our ability to drink very hot liquids or benefit from steam inhalation treatment. Although exposure to the high temperatures of hot tubs and saunas has become quite popular in recent years, Kneipp, Preissnitz, and Kellogg all believed that repeated and prolonged use could weaken the individual unless counteracted by frequent cold applications, such as showers or ablutions.2

A 2009 study of congestive heart failure patients showed improved biventricular cardiac function, increased output, decreased heart rate, and decreased blood pressure during warm water therapy over an 8-week period. The beneficial effects were found statistically significant during the therapy but did not change cardiac function overall. Authors concluded that warm water therapy is safe for patients with congestive heart failure.17 Similarly, a 2003 study showed improved mood, physical capacity, enjoyment, and heart failure-related symptoms (subjective), as well as significant decreases in heart rate and rate–pressure product at rest in patients with congestive heart failure. This study used warm water baths and cold water pours, which might account for the sustained therapeutic effect.18

In addition to the local hot applications discussed in previous sections, local hot applications are common and varied. For example, inhalation of steam for the treatment of the common cold has often been prescribed. Four studies19–22 published between 1987 and 1994 demonstrated the benefit of steam inhalation for nasal symptoms, with one of these studies21 demonstrating a decrease in inflammatory mediators in the local tissues.

A recent study of the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy using thermotherapy demonstrated a significant decrease in bladder outlet obstruction by using heated water in a closed loop catheter system.23 A Cochrane Review24 of interventions for chronic abacterial prostatitis concluded: “The routine use of antibiotics and alpha blockers for chronic abacterial prostatitis is not supported by the existing evidence. The small studies examining thermal therapy appear to demonstrate benefit of clinical significance and merit further evaluation.”

Physicians do not normally think of hot applications in the treatment of acute sports injuries. However, one recent study25 compared the use of hyperthermia to therapeutic ultrasound. In comparing 21 randomized patients with acute muscular injuries of different sites and severity to 19 controls, researchers discovered that after 2 weeks of treatment, the hyperthermia group had significantly less pain and faster hematoma resolution.

The presence of fever has long been associated with better survival and shorter duration of disease in cases of infection. Although the concept of modulating fevers in acute illness using sponging rather than antipyretics was discussed previously, hydrotherapy can also be used to enhance or induce a fever in acute or chronic infections to mimic or increase the body’s natural infection fighting capacity. Many studies have demonstrated the causes of that beneficial response. Four studies reviewed for this chapter26–29 demonstrated the activation and mobilization of blood mononuclear cells with hyperthermia treatments. One of these studies26 demonstrated significantly increased serum cortisol, plasma norepinephrine, and plasma epinephrine, and hypothesized that these elevated stress hormones were responsible for the rise in mononuclear cells. One study28 concluded that “fever-induced Hsp70 expression may protect monocytes when confronted with cytotoxic inflammatory mediators, thereby improving the course of the disease.”

General Guidelines for Hydrotherapy

General Guidelines for Hydrotherapy

1. The first rule of hydrotherapy is the same as for any therapy: treat the whole person. This involves considering all aspects, including medical history, current condition, current medications, and any other relevant information.

2. Use hydrotherapy treatments in a coordinated and integrated manner with any treatments or medications the individual is receiving.

3. To provide as precise a treatment as possible, grade the patient in terms of age, severity of problems, vitality, emotional state, circulatory condition, etc. A patient’s body temperature, along with their subjective general feeling of warmth or chilliness, should be used as a guide as to how intense the hot or cold used in a treatment should be. Be especially careful with young or elderly persons, and individuals who are chilly, have cardiac problems, are weak or debilitated, are obese, or have other severe physical compromises.

4. If a patient becomes chilled during a treatment, it may be necessary to stop the treatment and warm the person. Sometimes it may suffice to warm the person (by such means as hot drinks, friction rubs, additional blankets, or a hot water bottle to the feet) while continuing the treatment. If the person fails to warm after these attempts, then stop the treatments and warm him or her. Never allow a patient to become chilled to the point of shivering.

5. After a hydrotherapy treatment, avoid excessive heat or cold and/or drafts. The patient should be warmly dressed but not overly so.

6. It is best to do the treatment at an optimal time of day for that patient. It is best to do treatments before meals or at least one hour after a meal.

Cautions and Contraindications

If a patient has an adverse reaction, discontinue the treatment and assess the patient’s needs. If the patients are chilled, warm them; if lightheaded or dizzy, make sure they are well hydrated, assess for low blood sugar, and allow them to rest. If complaining of headache or nausea, the patient could be detoxifying, so encourage plenty of water and rest. Coaching the person in deep, slow-breathing exercises for several minutes often relaxes them and decreases the reaction.30 As with any treatment, use professional judgment as to the significance and cause of the patient’s response and employ appropriate intervention. Although undesired effects may occur during or immediately after treatments, they may also occur as long as 24 hours later. Therefore, it is important for practitioners to be available to patients during off-duty hours.

Pregnancy

What to do or take in pregnancy is always a concern. Bathing in hot water is no exception. Ridge and Budd,31 in a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, summarized these concerns and concluded “that for pregnant (or potentially pregnant) women using a spa pool at a water temperature of 40° C (104° F), any immersion longer than 10 minutes may be too long.”

Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease

Two studies published in 199832,33 demonstrated no adverse cardiovascular effects from bathing in water above 40° C and a response to heat stress no different from normotensive subjects.

Diabetes

For individuals with insulin-dependent diabetes, the application of heat to the extremities is to be approached with caution. As discussed previously, increased BF with hot application serves to conduct heat away from the area of application. In diabetics with poor circulation to the extremities, less heat is dissipated, and the local tissue temperature rises more than in tissues with normal circulation. It is safer to use less extreme temperatures in individuals with impaired circulation. Additionally, the application of heat increases tissue metabolism. With impaired circulation, tissue metabolic needs can quickly exceed the nutrients and oxygen available from the blood, and cells may die from oxygen depletion.30 Therefore, very hot applications to the extremities are generally contraindicated in diabetics, whereas mild to moderately hot applications can be quite effective for improving circulation and increasing healing of diabetic ulcers.

Hydrotherapy Techniques

Hydrotherapy Techniques

The various ways in which water may be applied to the human body therapeutically are only limited by the imagination of the practitioner. J.H. Kellogg, in his seemingly exhaustive treatise on hydrotherapy,2 devoted 541 pages to describing the techniques of hydrotherapy.

Compresses

Compresses are of four basic types: hot, cold, warming, and alternating hot and cold. They are each applied using cloth or other compress material, which is wrung out to the desired amount of moisture and then applied to any surface of the body. A single compress consists only of layers of the wet material, whereas a double compress is one in which the wet cloth is completely covered by dry material, usually wool, which acts to prevent cooling by evaporation or radiation.

Hot Baths

When hyperthermia treatments are given in the office, close supervision may allow more aggressive treatment. The water temperature may be increased to 106° F, and the duration of treatment may exceed 60 minutes. Patient tolerance is the key to performing safe and effective hyperthermia.

• Hypotension may result from hot immersions. When arising from the tub, patients may become lightheaded and lose their footing, so caution should be used in rising slowly and having assistance nearby.

• Patients should not take hyperthermia treatments on either an empty or full stomach. Too little food may result in a hypoglycemic episode, and too much food may result in nausea and vomiting.

• Hyperventilation sometimes occurs. On rare occasions patients may go into early tetany from respiratory alkalosis. Being present with the patient and coaching his or her breathing can prevent this.

• Headaches can and often do occur. These can be prevented by the early and frequent use of cold compresses to the head, face, and ears.

Neutral Baths

The primary effect of a neutral bath is to create a state of decreased excitation. This sedative effect, similar to that produced in deprivation tanks, calms the nervous system. A second effect is activation of the kidneys, creating increased urinary output due to the absorption of water into the body during periods of prolonged immersion.34 This is aided by the neutral temperature, which provides no stimulus for water loss through sweating. Nephrotic patients display increased phosphate excretion after prolonged immersion; therefore, they warrant special care when given prolonged immersion baths.35

Cold and Contrast Baths

Another option for contrast therapy is a shower or affusion. Having patients end their daily hot shower with a full body cold rinse is tonifying to the circulation and immune system. Ernst et al36 performed a long-term prospective study called “Prevention of Common Colds by Hydrotherapy.” The researchers compared 25 volunteers to 25 controls. Volunteers were asked to work up to a 5-minute hot shower followed by a 2-minute cold rinse. The study demonstrated a decrease in both the frequency and intensity of common colds in the treatment group compared with the control group.

Sitz Bath

Neutral sitz baths are more appropriate for situations of acute inflammation, such as cystitis and acute PID, as well as being effective for pruritus of the anus or vulva. The cold sitz bath is given immediately after a warm-to-hot sitz bath for 30 seconds to 8 minutes. It is important to ensure that the water level of the hot bath on the body is at least 1 inch above the level of the cold water. This ensures adequate warming of the area, thereby preventing chilling. Friction rubs to the hips during the cold sitz bath promote an increased reaction. The cold sitz bath is used mainly for its tonifying effects. It may be used for subinvolution of the uterus, metrorrhagia, atonic constipation, enuresis, atony of the bladder, and chronic prostatic congestion. Because it increases the tone of the smooth muscles of the uterus, bladder, and colon, it lessens the tendency to bleed from the uterus, the lower bowel, and rectum. It is necessary to provide adequate coverings during neutral and cold sitz baths to avoid chilling.

Constitutional Hydrotherapy

Constitutional hydrotherapy was, as stated previously, developed by O.G. Carroll as an application of first hot, then cold, to the trunk, both front and back, along with low volt electrical stimulation to tonify the digestive organs and enhance the effects of the water applications. This therapy utilizes both contrast hydrotherapy and warming compress effects. Apart from contrast hydrotherapy applications, it is the most generally useful of the various hydrotherapy treatments and is commonly used to balance body functions, strengthen the immune system, and promote healing, as well as being a useful adjunct to detoxification. A pilot study37 completed in 2008 at the Bastyr Center for Natural Health on human immunodeficiency virus positive patients showed a statistically significant increase in energy and decrease in body fat and a trend toward increased physical function along with a decrease in pain after a course of treatment with constitutional hydrotherapy. Fifty-eight percent of participants showed a decrease in systolic blood pressure. There was also a sizable decrease in C-reactive protein levels.

Constitutional hydrotherapy may be used as an adjunct to the treatment of any condition. It may be used to treat acute conditions such as upper respiratory infections, bronchitis, asthma, and gastrointestinal infections, and chronic conditions such as irritable bowel, ulcerative colitis, pre-menstrual syndrome, and arthritis, as well as conditions related to nervous system dysregulation such as insomnia or anxiety. (As a general rule of thumb “when in doubt, try constitutional hydrotherapy.”) Boyle and Saine’s Lectures in Naturopathic Hydrotherapy contains an excellent write-up on the constitutional hydrotherapy procedure.38

Wet Sheet Pack

The wet sheet pack is one of the most useful of all hydrotherapy procedures. It may be done either in the office or as a home treatment, if adequate direction is provided. It requires from 1 to 3 hours, depending on the patient’s condition. Understanding the process completely before using this treatment is important. Lectures in Naturopathic Hydrotherapy by Boyle and Saine outlines the wet sheet pack procedure in detail for practitioners.38

• Tonic stage. This stage may last from 2 to 15 minutes and is finished when the patient no longer perceives the sheet as being cold. This phase is intensely alterative to the body due to the intense thermic reaction induced. The length of this stage is directly dependent on the amount of water left in the sheet. For weak or exhausted patients, the sheet should be wrung out as completely as possible. For young, strong individuals for whom a more tonifying treatment is desired, more water may be left in the sheet.

• Neutral stage. Once the sheet reaches body temperature, the person no longer feels cold. At this time, the neutral phase begins. It may last from 15 minutes to an hour or longer, depending on the vitality of the patient. During this phase, there is a sense of calm that is similar to that experienced during a neutral bath. Often the patient falls asleep during this phase. This stage is indicated in cases of insomnia, anxiety, and delirium. To prolong the neutral phase, provide only adequate covering to prevent the patient feeling cool. Greater amounts of blankets trap more heat, and the neutral phase finishes sooner.

• Heating stage. As heat accumulates beneath the blankets, the patient gradually senses the warming and eventually begins to show light perspiration on the forehead. The time between the patient feeling warm and the beginning of perspiration is known as the heating phase. This may last from 15 minutes to an hour.

• Elimination stage. The final stage begins when the body begins to perspire. In a febrile patient, this stage is reached sooner. This stage is especially beneficial for those patients in a detoxification process, such as from alcohol, tobacco, coffee, or other toxins. It may also be used with acute infections, such as colds, flu, or bronchitis. Certain conditions that affect the skin, such as jaundice, may also benefit from this stage, as well as acute inflammatory conditions, such as arthritis.

During the elimination phase, it is important to provide adequate fluid to the patient. Herbal teas, used for either their diaphoretic or therapeutic effects, are most appropriate. This phase may last up to an hour. The treatment should be ended quickly if the patient begins to feel chilled or becomes uncomfortable.

Sauna

Saunas can be wet or dry depending on their heat source. Steam saunas use water as their source of heat and are an excellent general hyperthermic treatment. Saunas have also shown efficacy in detoxification protocols supporting excretion of toxins through the skin. A recent review of the benefits and risks of sauna bathing39,40 concluded the following:

• It is well tolerated by most healthy adults and children.

• It is safe during uncomplicated pregnancy.

• It may help lower blood pressure and increase left ventricular ejection in patients with congestive heart failure.

• It produces transient improvement in pulmonary function, which may be helpful for patients with asthma and chronic bronchitis.

• It decreases pain and increases mobility in patients with rheumatic diseases.

• It may be contraindicated in patients with unstable angina pectoris, recent myocardial infarction, and severe aortic stenosis.

• It is safe for patients with stable angina pectoris and old myocardial infarction.

• Krop40 published a case study in 1998 demonstrating the usefulness of sauna in the detoxification of a patient with 20 years’ duration chemical sensitivity resulting from low-level exposure to solvents.

Summary

Summary

Hydrotherapy provides naturopathic physicians and the general public alike with an effective and inexpensive form of treatment for many conditions, as well as a time-tested method for stimulating the vital force and maintaining health. This chapter has touched on only a few of the many techniques developed over the years. Naturopathic students, patients, and physicians wishing to learn more about the uses and techniques of hydrotherapy are encouraged to read Father Sebastian Kneipp’s My Water Cure and Boyle and Saine’s Lectures in Naturopathic Hydrotherapy.38 Both resources contain instruction in how to use a wide variety of hydrotherapy techniques to regain and maintain health.

1. Hippocrates. Hippocratic writings. In: The Great Books. Chicago: William Benton; 1952.

2. Kellogg J.H. Rational hydrotherapy, 4th ed., Battle Creek, MI: Modern Medicine; 1923:721–722.

3. Lindlahr H. Nature Cure, 20th ed., Holicong, PA: Wildside Press, 1922.

4. Engel J.P., Watkin G., Erickson D.J., et al. The effect of contrast baths on the peripheral circulation of patients with R.A. Arch Phys Med. 1950;31:135–144.

5. Woodmansey A., Collins D.H., Ernst M.M. Vascular reactions to the contrast bath in health and in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 1938;ii:1350–1354.

6. Krusen F.H. Physical medicine; the employment of physical agents for diagnosis and therapy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1941.

7. Moor F.B., Peterson S., Manwell E., et al. Manual of hydrotherapy and massage. Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press; 1964. 9-15, 964

8. Hewlett A.W. The effect of some hydrotherapeutic procedures on the blood flow in the arm. Arch Intern Med. 1911;8:591–608.

9. Stewart G.N. The effect of reflex vasomotor excitation on the blood flow in the hand. Heart. 1912;3:76–84.

10. Briscoe G. Observations on venous and capillary pressures with special reference to the Raynaud Phenomena. Heart. 1918;7:35.

11. Poulton E.P. An experimental study of certain visceral sensations. Lancet. 1928;ii:1223–1277.

12. Bing H.J., Tobiassen E.S. Viscerocutaneous and cutovisceral abdominal reflexes. Acta Med Scand Supp. 1936;78:824–833.

13. Fisher E., Soloman S. Physiological responses to heat and cold. Licht S., ed. Therapeutic heat and cold, 2nd ed, New Haven, CT: Elizabeth Licht, 1965.

14. Schlesinger N., Detry M.A., Holland B.K., et al. Local ice therapy during bouts of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:331–334.

15. Aksoylar S., Aksit S., Caglayan S., et al. Evaluation of sponging and antipyretic medication to reduce body temperature in febrile children. Acta Paediatr Jpn. 1997;39:215–217.

16. Agbolosu N.B., Cuevas L.E., Milligan P., et al. Efficacy of tepid sponging versus paracetamol in reducing temperature in febrile children. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1997;17:283–288.

17. Grüner Sveälv B., Cider A., Scharin Täng M., et al. Benefit of warm water immersion on biventricular function in patients with chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2009;7:33.

18. Michalsen A., Lüdtke R., Bühring M., et al. Thermal hydrotherapy improves quality of life and hemodynamic function in patients with chronic heart failure. Am Heart J. 2003;146(4):728–733.

19. Hendley J.O., Abbott R.D., Beasley P.P., et al. Effect of inhalation of hot humidified air on experimental rhinovirus infection. JAMA. 1994;271:1112–1113.

20. Georgitis J.W. Nasal hyperthermia and simple irrigation for perennial rhinitis. Changes in inflammatory mediators. Chest. 1994;106:1487–1492.

21. Georgitis J.W. Local hyperthermia and nasal irrigation for perennial allergic rhinitis: effect on symptoms and nasal airflow. Ann Allergy. 1993;71:385–389.

22. Ophir D., Elad Y. Effects of steam inhalation on nasal patency and nasal symptoms in patients with the common cold. Am J Otolaryngol. 1987;8:149–153.

23. Cioanta I., Muschter R. Water-induced thermotherapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Tech Urol. 2000;6:294–299.

24. McNaughton Collins M., MacDonald R., Wilt T. Interventions for chronic abacterial prostatitis (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. Oxford: England; 2003. Update Software

25. Giombini A., Casciello G., Di Cesare M.C., et al. A controlled study on the effects of hyperthermia at 434 MHz and conventional ultrasound upon muscle injuries in sport. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2001;41:521–527.

26. Kappel M., Stadeager C., Tvede N., et al. Effects of in vivo hyperthermia on natural killer cell activity, in vitro proliferative responses and blood mononuclear cell subpopulations. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;84:175–180.

27. Kappel M., Barington T., Gyhrs A., et al. Influence of elevated body temperature on circulating immunoglobulin-secreting cells. Int J Hyperthermia. 1994;10:653–658.

28. Oehler R., Pusch E., Zellner M., et al. Cell type-specific variations in the induction of hsp7O in human leukocytes by feverlike whole body hyperthermia. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:306–315.

29. Zellner M., Hergovics N., Roth E., et al. Human monocyte stimulation by experimental whole body hyperthermia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2002;114:102–107.

30. Thrash A.M., Thrash C.L. Home remedies. Seale, AL: Thrash; 1981.

31. Ridge B.R., Budd G.M. How long is too long in a spa pool? N Engl J Med. 1990;323:835–836.

32. Allison T.G., Reger W.E. Comparison of responses of men to immersion in circulating water at -40.0 and 41.5 degrees C. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1998;69:845–850.

33. Kellogg D.L., Jr., Morris S.R., Rodriguez S.B., et al. Thermoregulatory reflexes and cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress in hypertensive humans. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:175–180.

34. Epstein M., Saruta T. Effect of water immersion on renin, aldosterone, and renal sodium handling in normal man. J Appl Physiol. 1971;31:368–374.

35. Brown C., Sutton J.V., Adler A., et al. Renal calcium and magnesium handling in water immersion in nephrotic patients. Nephron. 1983;33:17–20.

36. Ernst E., Wirz P., Pecho I. Prevention of common colds by hydrotherapy. Physiotherapy. 1990;76:207–210.

37. Bradley R., Pillsbury C., Huyck A., et al. Clinical pilot of constitutional hydrotherapy in HIV+ adults. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. Abstracts From the 2009 North American Research Conference on Complementary & Integrative Medicine. 2009;15:3.

38. Boyle W., Saine A. Lectures in Naturopathic Hydrotherapy. Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications; 1988;. 135-145,123-128

39. Hannuksela M.L., Ellahham S. Benefits and risks of sauna bathing. Am J Med. 2001;110:118–126.

40. Krop J. Chemical sensitivity after intoxication at work with solvents: response to sauna therapy. J Altern Complement Med. 1998;4:77–86.