46. Hydrocephalus

Definition

Hydrocephalus is a disturbance or interruption of the formation, flow, or absorption of cerebrospinal fluid. All types of hydrocephalus culminate in increased volume of fluid within the central nervous system’s relatively closed spaces.

Types of Hydrocephalus

• Arrested

• Benign external

• Communicating

• Congenital

• Noncommunicating

• Normal pressure

• Obstructive

Incidence

In the United States congenital hydrocephalus occurs at the rate of about 3:1000 live births. The frequency of acquired hydrocephalus is not documented. Internationally there are no estimates on the frequency of congenital or acquired hydrocephalus.

Etiology

Congenital Causes, Infants and Children

• Agenesis of the foramen of Monro

• Arnold-Chiari malformation (Types I and II)

• Bickers-Adams syndrome∗

∗See Appendix G: Rare Syndromes.

• Congenital toxoplasmosis

• Dandy-Walker malformation∗

• Stenosis of the aqueduct of Sylvius

Acquired Causes, Infants and Children

• Iatrogenic hypervitaminosis A

• Idiopathic

• Increased venous sinus pressure

• Infections (meningitis, cysticercosis)

• Intraventricular hemorrhage

• Mass lesions

|

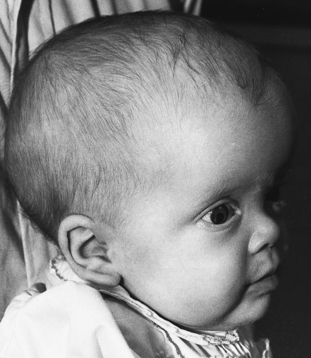

| Hydrocephalus. Child with enlarged head caused by hydrocephalus. |

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus and Causes, Adult

• Congenital aqueductal stenosis

• Head injury

• Idiopathic

• Meningitis

• Previous posterior fossa surgery

• Subarachnoid hemorrhage

• Tumor

Signs and Symptoms

Manifestations are influenced by the following five factors:

1. Cause

2. Duration

3. Obstruction location

4. Patient age

5. Rapidity of onset

Infant

• Irritability

• Poor feeding

• Reduced activity

• Vomiting

Child

• Blurred vision

• Difficulty walking

• Double vision

• Drowsiness

• Headaches

• Neck pain

• Slowing mental capacity

• Spasticity

• Stunted growth or sexual maturation

• Vomiting

Adult

• Blurred vision

• Cognitive deterioration

• Difficulty walking

• Double vision

• Drowsiness

• Headaches

• Incontinence

• Nausea

• Neck pain

• Vomiting

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

• Aggression

• Dementia

• Gait disturbances

• Parkinson-like symptoms

• Seizures

• Urinary incontinence

Medical Management

Medical interventions are used to delay surgical intervention and are not typically effective in the long-term management of hydrocephalus. Medical intervention may work well in a preterm infant who has posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus, but not acute hydrocephalus, by fostering normal tissue development and eventual spontaneous resumption of normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) absorption. Medication may be used to either decrease CSF production by the choroid plexus or to increase the reabsorption of CSF that is produced.

Definitive treatment for hydrocephalus is surgical intervention, including the placement of shunts. Five shunting methods include:

1. Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt (the most common)

2. Ventriculoatrial (VA) shunt

3. Lumboperitoneal shunt (reserved only for communicating hydrocephalus, CSF fistula, or pseudotumor cerebri)

4. Torkildsen shunt (rare and only effective for acquired obstructive hydrocephalus)

5. Ventriculopleural shunt (used only when all other shunts are contraindicated)

There are alternatives to shunting, including choroid plexectomy or choroid plexus coagulation, tumor excision, stenosed aqueduct opening (has the highest morbidity and the lowest success rate), and third ventricle floor endoscopic fenestration (contraindicated in communicating hydrocephalus). Rapid-onset or acute hydrocephalus with increasing intracranial pressure is an emergency situation. Four measures that may be undertaken include:

1. Ventricular taps (infant)

2. Open ventricular drainage (child and adult)

3. Lumbar puncture in posthemorrhagic and postmeningitic hydrocephalus

4. VP or VA shunt procedure

Complications

• Chronic papilledema

• Cognitive dysfunction

• Gait disturbances

• Incontinence

• Occlusion of posterior cerebral arteries

• Optic chiasm compression due to third ventricle dilation

• Visual disturbances

Specific to Medical Treatment

• Electrolyte imbalance

• Metabolic acidosis

Specific to Surgical Intervention

• Abdominal organ perforation

• Arachnoiditis

• CSF ascites

• Endocarditis

• Extraneural metastasis

• Hardware erosion

• Increased(ing) intracranial pressure

• Infection

• Inguinal hernia

• Intestinal obstruction

• Periarteritis

• Pulmonary hypertension

• Radiculopathy

• Septicemia

• Shunt embolus

• Shunt occlusion

• Subdural hematoma or hygroma

• Volvulus

Anesthesia Implications

The first consideration is the nature of the hydrocephalus. Is the case acute, subacute, or chronic? Does the patient have increased intracranial pressure (ICP)? Acute hydrocephalus with signs of increased(ing) ICP is an emergency situation. The patient should be induced, intubated, and hyperventilated fairly quickly. Because succinylcholine produces an increase in the ICP, it should be avoided in favor of a fast-onset, nondepolarizing muscle relaxant. Succinylcholine should also be omitted if the patient is being treated in the short term with either acetazolamide or furosemide or both, because of the potential hypokalemia that either or both can produce.

The anesthetist must be ever mindful of the importance of monitoring the patient’s cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP). Induction, particularly in the emergent situation above, must be accomplished in such a manner as to minimize the drop in the patient’s mean arterial pressure (MAP).

Remember: CPP = MAP − ICP

Premedication, although not specifically contraindicated in the patient with hydrocephalus, must be undertaken judiciously to avoid oversedation, hypoventilation, hypoxia, hypercarbia, increased cerebral blood volume, and elevation of the patient’s ICP.

The anesthetist should provide mild hyperventilation during induction and during the initial phase of the surgical intervention to “relax” the brain—reduce the level of CO 2 and constrict the cerebral blood vessels. As part of this goal, the anesthetist may need to administer an osmotic diuretic to reduce the circulating volume and further lower the cerebral blood volume. Administering such a medication too rapidly may induce a seizure, systemic hypotension, pulmonary hypertension, and congestive heart failure, among other untoward actions.