Hydration and Dehydration

Hydration and Dehydration Assessment and Treatment

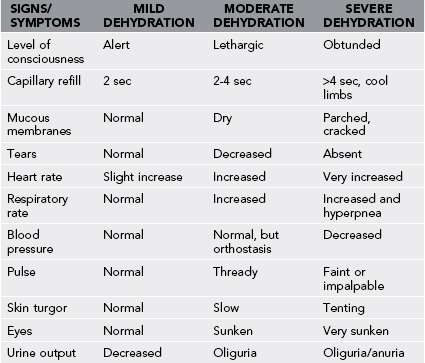

Water accounts for 50% to 70% of the body’s weight. Because sweating involves loss of body mass, measuring changes in body weight is the simplest way to rapidly assess hydration status. However, wilderness first aid kits will almost never include an accurate scale with which to weigh a patient, so estimation of hydration status must rely on other observations (Table 46-1). Prevention of dehydration is key (Table 46-2).

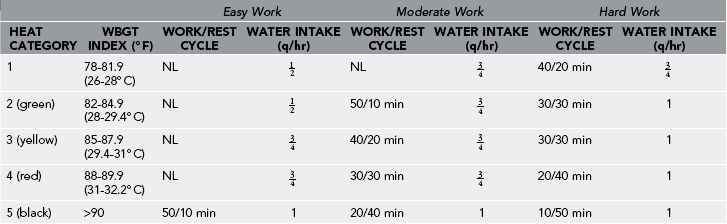

Table 46-2

Fluid Replacement Guidelines for Warm-Weather Training (Applies to Average Acclimated Soldier Wearing BDU in Hot Weather)*

BDU, Battle dress uniform; NL, no limit to work time per hour; WBGT, wet bulb global temperature.

Rest means minimal physical activity (sitting or standing), accomplished in shade if possible.

*The work/rest times and fluid replacement volumes will sustain performance and hydration for at least 4 hours of work in the specified heat category. Individual water needs will vary  quart per hour.

quart per hour.

From Montain SJ, Latzka WA, Sawka MN: Fluid replacement recommendations for training in hot weather. Mil Med 164:502, 1999.

Urine Markers

Hydration Strategies

1. Drink 500 mL (2 cups) of fluid about 4 hours before endurance or strenuous activity to promote adequate hydration and allow time for excretion of excess water. If no urine, or concentrated urine, follows, drink another 300 mL ( cups) 2 hours before activity.

cups) 2 hours before activity.

2. Replace water losses caused by sweating at a rate equal to the sweat rate (see Table 46-2).

a. Sweat losses range from 0.3 to 1.2 L/hr for an individual doing mild work while wearing cotton clothes.

b. Sweat losses range from 1 to 2 L/hr for an individual doing mild work and wearing nonpermeable clothing.

c. Sweat losses range from 1 to 2.5 L/hr for an individual doing strenuous work or during high exercise intensity in a hot climate.

3. The perception of thirst is a poor indicator of hydration. Individuals can be 2% to 8% dehydrated before feeling thirsty.

4. Unless an activity is prolonged and in hot weather with large volumes of sweat loss, beverages containing electrolytes and carbohydrates offer little advantage over water in maintaining hydration or electrolyte concentration or in improving intestinal absorption. The Institute of Medicine recommends that in the instance of prolonged activity in hot weather, fluid replacement should contain 20 to 30 mEq/L sodium (chloride as the anion), approximately 2 to 5 mEq/L potassium, and approximately 5% to 10% carbohydrate.

5. Fluid-replacement beverages that are sweetened (with carbohydrates or artificial sweeteners) and cooled (to between 15° and 21° C [59° and 69.8° F]) stimulate ingestion of more fluid.

6. Meals should be consumed regularly to return normal electrolyte losses.

7. During prolonged exercise, frequent (every 15 to 20 minutes) consumption of moderate (150 mL [ cup]) to large (350 mL [

cup]) to large (350 mL [ cups]) volumes of low-osmolarity fluid may improve the gastric emptying rate.

cups]) volumes of low-osmolarity fluid may improve the gastric emptying rate.

8. Optimal performance is attainable only with sufficient drinking during exercise to minimize dehydration. Even low levels of dehydration (1% loss of body mass) impair cardiovascular and thermoregulatory responses and reduce capacity for exercise.

9. To restore hydration status after exercise, a person should consume 1 L ( cups) of fluid for every kilogram of weight lost during the activity. Consumption of normal meals and snacks with sufficient volume of plain water will restore euhydration.

cups) of fluid for every kilogram of weight lost during the activity. Consumption of normal meals and snacks with sufficient volume of plain water will restore euhydration.

quarts. Daily fluid intake should not exceed 12 quarts.

quarts. Daily fluid intake should not exceed 12 quarts.